#art and literature

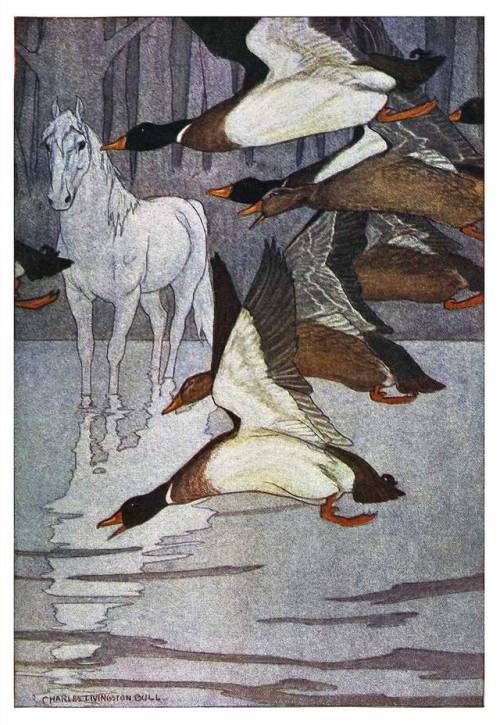

“The southward journeying ducks, which would drop with loud quacking and splashing into the shallows.” Color process illustration by Charles Livingston Bull for the book, The Haunters of the Silences, written by Charles George Douglas Roberts. Published in 1907.

Post link

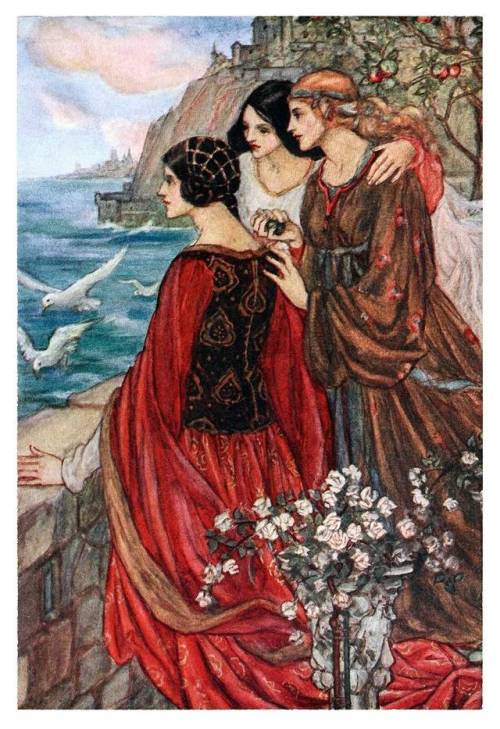

“Beneath an apple-tree our heads stretched out toward the sea.” Color process illustration by Florence Harrison, for the book, Early Poems of William Morris, published in 1914.

Post link

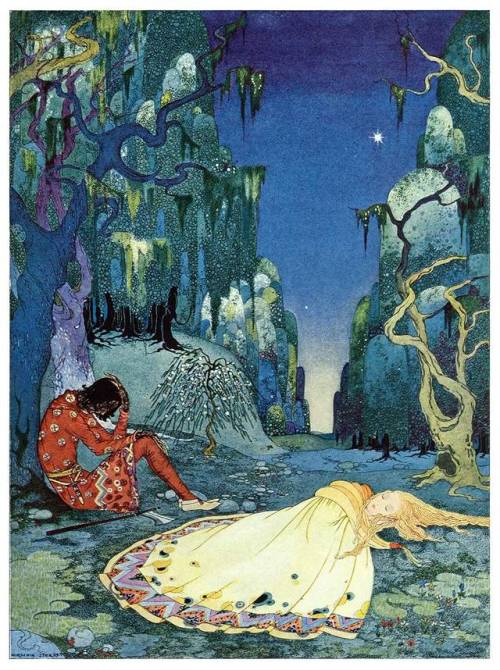

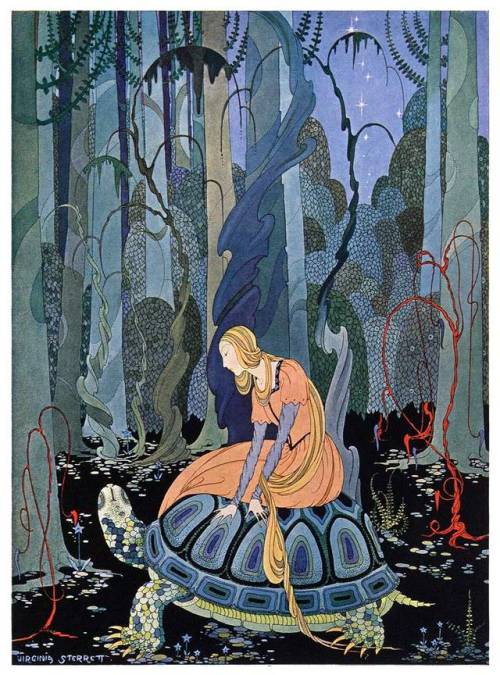

“Violette consented willingly to pass the night in the forest.” Color process illustration by Virginia Frances Sterrett for the book, Old French Fairy Tales, published about 1920.

Post link

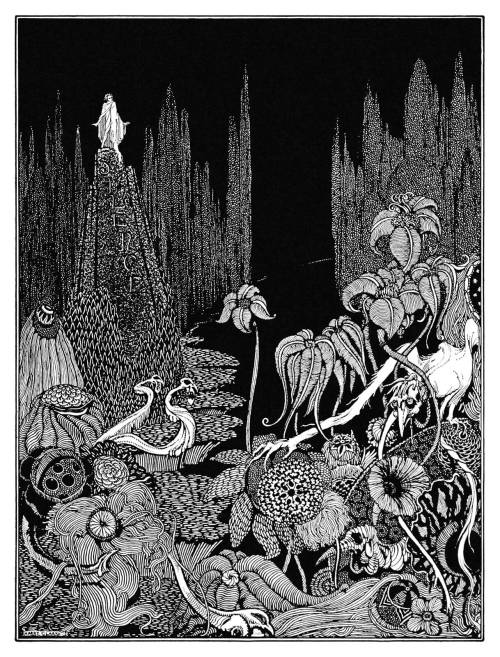

“But there was no voice throughout the vast, illimitable desert.” Portrait illustration by Harry Clarke, for Edgar Allan Poe’s book, Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Post link

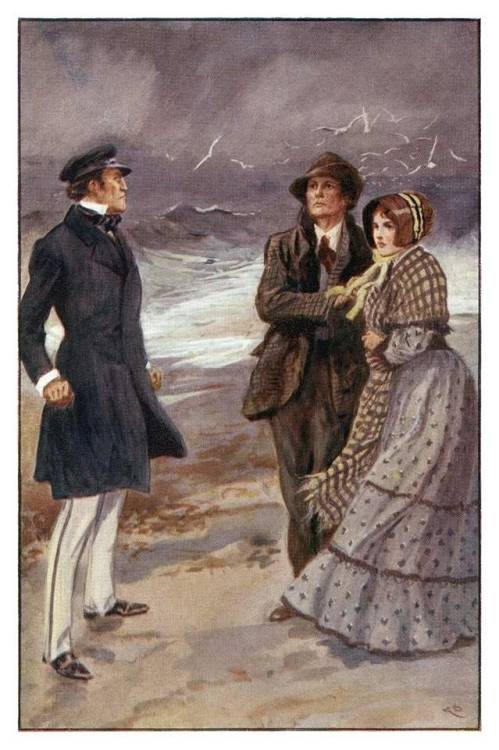

“That girl, as you call her, is my wife.” Color process illustration by Gordon Browne, for Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel, The Pavilion on the Links, published in 1913.

Post link

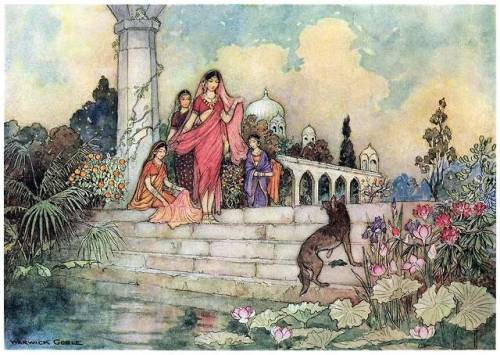

“The jackal … opened his bundle of betel leaves, put some into his mouth, and began chewing them.” Color process illustration by Warwick Goble, for the children’s book, Folk-Tales of Bengal, published by Macmillan and Company in 1912.

Post link

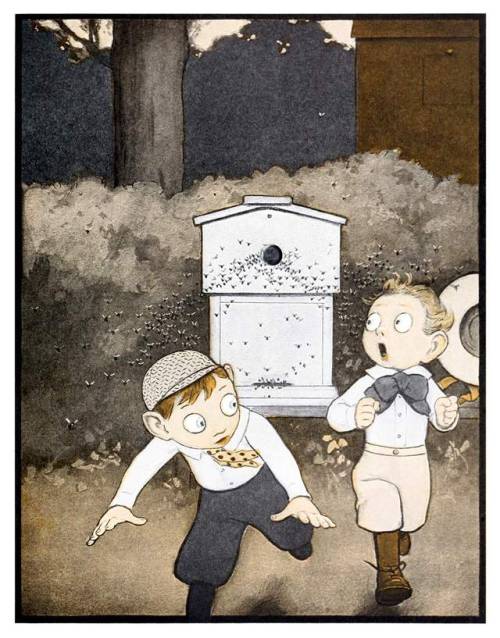

“The startled swarm came streaming out

In temper hot and baneful,

And drove the foe in awful rout,

With volleys sharp and painful.”

Color process illustration by Peter Newell, for his children’s book, The Hole Book, published about 1908 by Harper & Brothers.

Post link

“The maid-of-honor blooming fair:

The page has caught her hand in his:

Her lips are sever’d, as to speak:

His own are pouted to a kiss:

The blush is fix’d upon her cheek.”

Wood engraving by an unknown artist for Lord Alfred Tennyson’s book, The Day Dream, published in 1886 by E. P. Dutton & Co.

Post link

“She went to the cobbler’s,

To buy him some shoes,

But when she came back

He was reading the news.”

Wood engraving by the Dalziel Brothers, based on the artwork of an unknown artist. From Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes, published in 1877 by George Rutledge & Sons, London.

Post link

“They were three months passing through the forest.” Color process illustration by Virginia Frances Sterrett for the book, Old French Fairy Tales, published about 1920.

Post link

Thom Gunn was an openly gay poet in San Francisco. Although he never contracted HIV, he wrote the most famous volume of poetry about living through the epidemic. The title poem, “The Man With Night Sweats,” is even quoted in Emily Nussbaum’s review of the HBO version of The Normal Heart in The New Yorker. It’s short enough to reprint here in full.

The Man With Night Sweats

I wake up cold, I who

Prospered through dreams of heat

Wake to their residue,

Sweat, and a clinging sheet.

My flesh was its own shield:

Where it was gashed, it healed.

I grew as I explored

The body I could trust

Even while I adored

The risk that made robust,

A world of wonders in

Each challenge to the skin.

I cannot but be sorry

The given shield was cracked,

My mind reduced to hurry,

My flesh reduced and wrecked.

I have to change the bed,

But catch myself instead

Stopped upright where I am

Hugging my body to me

As if to shield it from

The pains that will go through me,

As if hands were enough

To hold an avalanche off.

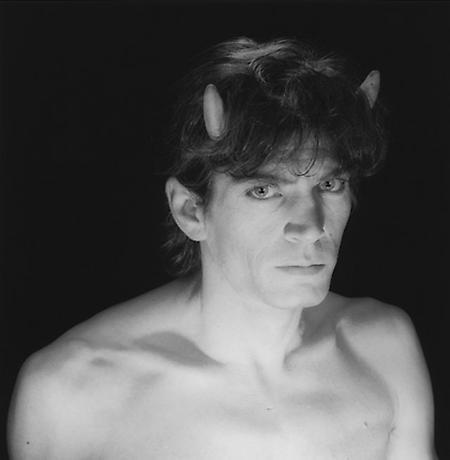

(Self Portrait, 1985)

Robert Mapplethorpe was born in 1946 in Queens, New York. He studied drawing, painting, and sculpture at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, and after college lived in the Chelsea Hotel with his close friend Patti Smith: she’s written about those years in her award-winning memoir, Just Kids.

(More images and history under the cut; all SFW.)

Mapplethorpe moved into photography in the 1970s, creating iconic album cover art for Patti Smith and Television. As the 1970s continued, he became increasingly interested in photographing the local S&M scene. As the biography on the Mapplethorpe Foundation site puts it,

The resulting photographs are shocking for their content and remarkable for their technical and formal mastery. Mapplethorpe told ARTnews in late 1988, “I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.”

Those were not his only subjects: among other photos, he did a series in collaboration with Lisa Lyon, the first World Women’s Bodybuilding Champion. and he photographed many other artists, including this photo I’ve always loved of sculptor Louise Bourgeois holding one of her own works (possibly NSFW). His works are classically, almost austerely beautiful, and highly stylized. In 1986, his exhibit of eroticized photos of black men created controversy when it was accused of being exploitative and dehumanizing in its stylized depictions.

In the last years of his life, Mapplethorpe’s work became more popular, and there were three exhibits of his work in 1988. Although it was widely known in the art world that Mapplethorpe had been diagnosed with AIDS in 1986, the New York Times review of his Whitney Museum exhibit called it a “mid-career retrospective,” ignoring the disease.

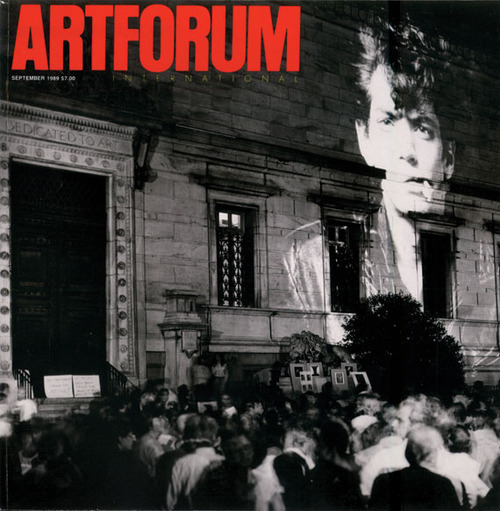

One of those 1988 exhibits, “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment,” traveled from Philadelphia to Chicago, and was then supposed to be shown at the Corcoran Gallery in DC. Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC), an extremely conservative and vocal Republican leader, learned that the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) had given $30,000 to the Philadelphia museum towards the cost of curating the show, and he got 100 members of the US Congress to write a letter of complaint to the NEA about subsidizing materials of “a morally repugnant nature.” The Corcoran, worried about its own NEA funding, pulled out of the show.

As a result, the Corcoran lost $1.5 million in promised bequests, several artists forbade their work from being shown there, and membership dropped by 10%. The exhibit – which kept the explicit works in a separate age-restricted gallery – was taken in instead by the Washington Project for the Arts, which had over 35,000 visitors in three weeks – still a record there. A large protest outside the Corcoran, uniting free speech advocates, artists, and gay rights activists, projected works from the show onto the Corcoran’s walls.

The exhibit would create controversy again in 1990, when the curator of Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center was charged with obscenity for staging the exhibit.

The last image you saw when leaving “The Perfect Moment” was Mapplethorpe’s final self-portrait, taken just months before his death.

(Self-Portrait, 1988)

In this late photograph, Mapplethorpe is no longer playing a role, as he did in so many of his earlier self-portraits. It was taken a few months before he died from an AIDS-related illness in 1989. In it he faces straight ahead, as if he were looking death in the face. The skull-headed cane that he holds in his right hand reinforces this reading. Mapplethorpe is wearing black, so that his head floats free, disembodied, as if he were already half-way to death. Mapplethorpe even photographs his head very slightly out of focus (compared with his hand) to suggest his gradual fading away.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was a Cuban-born American artist, working primarily in minimalist installations and sculptures. Many of his best-known works were created in memory of his partner, Ross Laycock, who also died of AIDS.

Untitled (1991) is a billboard that was originally installed in twelve locations throughout New York City. This photo is from a MoMA re-installation in 2012.

The image of an empty, slept-in bed, created the same year as Laycock’s death, is an act of mourning:

When people ask me, “Who is your public?” I say honestly, without skipping a beat, “Ross.” The public was Ross. The rest of the people just come to the work.“ - ArtPress Interview

But it is also an assertion that their private lives are worthy of public consideration, claiming a dignity for their intimacy that years of hysteria around the epidemic had taken away.

Even more moving is "Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” 1991, which is on display in the Art Institute of Chicago.

To quote the catalogue from a recent Brooklyn Museum show the piece was included in:

González-Torres created a spill of candies that approximated Ross’s weight (175 lbs.) when he was healthy. Viewers are invited to take away a candy until the mound gradually disappears; it is then replenished, and the cycle of life and death continues. While González-Torres wanted the viewer/participant to partake of the sweetness of his own relationship with Ross, the candy spill also works as an act of communion. More darkly, the steadily diminishing pile of cheerfully wrapped candies shows the dissolution of the gay community, as society ignored the AIDS epidemic. In the moment that the candy dissolves in the viewer’s mouth, the participant also receives a shock of recognition at his or her complicity in Ross’s demise.

In 1995, while he was still alive, Gonzalez-Torres was rejected from the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale in part because his work was considered too political. In 2007, he was chosen to represent the US at the Biennale, with some of his initial concepts for the 1995 show included: he was only the second posthumous representative the US has ever had at this important international art event.