#northwest passage

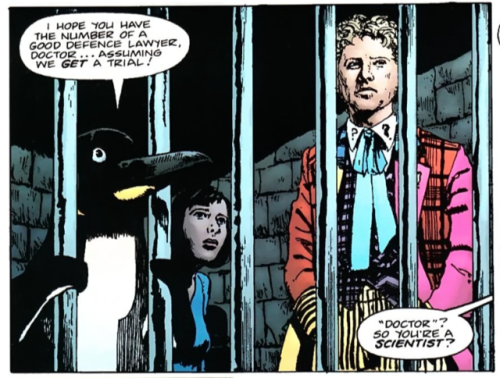

So in the Doctor Who comics… the Doctor and Peri travel with Frobisher… a shapeshifting penguin.

Ok, I couldn’t help but be a complete nerd about this. The penguin’s name is Frobisher. Penguins are from the opposite side of the earth, but I can’t help but think it was named after this guy:

Sir Martin Frobisher. He was a 16th century English privateer and explorer and one of the earliest explorers to set out in search of the Northwest passage through northern Canada (as opposed to across the North American continent, which was a thing at the time).

He made three trips to northern Canada and had reached as far north as Baffin Island. He tried and failed to establish a settlement in Canada, and his futile search for gold ended in a loss of support from the crown for any further arctic voyages, although with the limited technology of exploration at the time he was never likely to have successfully penetrated much deeper into the passage or much further north. He has a bay named after him on the southern end of Baffin Island, at the ‘entrance’ to the Northwest Passage. And apparently also a a penguin that spits fish in Colin Baker’s lap. Who knew.

Post link

Narrative of a second voyage in search of a north-west passage

Sir John Ross’s version of his failed attempt at the Northwest Passage. As always, keep in mind these books are official accounts and though written by those who participated have a certain aura about them.

Roald Amundsen photographed in 1906 after completing the first single vessel navigation of the Northwest Passage. The key to Amundsen’s success was a combination of the right ship and the right lifestyle. For his journey he chose the Gjøa, a small, shallow draft 70 foot vessel able to maneuver the labyrinth that is arctic Canada. His lifestyle during the journey was patterned after the Inuit, not only in clothing but also in the small size of his crew. Only five men traveled with him, a number that could be supported by the land with (relative) ease.

Sir John Franklin and Francis Crozier were among the most renowned polar explorers of the 19th century, and their disappearance triggered a decades-long series of rescue missions. In 1845 the duo led two ships on an expedition to discover the elusive Northwest Passage—the sea route linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But after passing Baffin Island that July, the expedition vanished without a trace.

It was two years before a search party arrived from England, and only then did some of the terrifying details of the explorers’ fate finally come to light. The investigations revealed that Franklin and Crozier’s vessels had become trapped in pack ice during the winter of 1846-1847. While the expedition had three years’ worth of supplies, all the provisions had been sealed with lead, which almost certainly contaminated the sailors’ food. The crew soon became weakened and delirious from lead poisoning, and at least 20 men—including Franklin—perished by mid-1848. Natives who came in contact with the expedition later claimed that Crozier tried to lead the survivors south in search of help. Most if not all of the men are believed to have died during the journey, and recent evidence shows some even resorted to cannibalism. Spurred on by Franklin’s widow, as many as 50 ships would later travel to Canada in an attempt to locate the lost expedition, but the bodies of Franklin and Crozier—along with the wrecks of their two ships—have never been recovered.

Source:www.history.com

Back to the Arctic with the first part of a commission for @dramatic-opening-shot , a view from Erebus on icebound Terror

Beuty in the wind

Graves of Ice, by John Wilson. George Chambers was a real person, but much of the story is mere conjecture, due to the fact that so few written records about the Expedition have been found. Perhaps that’s why it doesn’t bother me too much that George comes off as an unreliable narrator.

I first learned about the Franklin Expedition from Margaret Atwood’s short story collection Wilderness Tips. So when I first read this book, I had a pretty good idea of how it was going to end. Even still, the story was engaging.

Goodreads star rating: 4/5

It’s another chilly, snowy winter Friday at Hagley Library, so here’s a literal icebreaker to move us along to the weekend and, hopefully, warmer days ahead. This photograph shows the SS Manhattan, a ship built in 1962 as an oil tanker at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts, but which began retrofitting operations in 1968 for a new life as an icebreaker.

When retrofitting was complete in 1969, they made the Manhattan the largest American merchant ship in history, the largest icebreaking ship in history, and well-suited for its next journey; becoming the first commercial ship to traverse the Northwest Passage.

The ship made its journey later that year, setting off an international incident over Canada and the United States’ disputed sovereignty claims to the region. The goal of the journey was to test the feasibility of the route as a permanent, year-round transport option for Alaskan oil shipments. Canada’s desire to make exclusive claims to the waterway rested in part on the nation’s concern over pollution and clean-up liabilities had the SS Manhattan failed in its objective and loosed its cargo into the sea.

Fortunately, that didn’t happen. The 1969 voyage successfully transported oil across the Northwest Passage without incident, and another voyage was made in 1970. The Manhattan sustained considerable damage during both trips, however, making the costs of shipping via this route unsustainable at the time.

This photograph is part of Hagley Library’s collection of Lukens Steel Company photographs (Accession 1972.360). Lukens Steel Company was a medium-sized producer of specialty steel products and one of the top three producers of steel plate in the United States. The company is noted for being the first industrial company in the United States led by a woman, Rebecca Lukens (1794-1854).

A selection of material from this collection has been digitized, including woodcuts showing the early history of the mill, interior and exterior views of factory buildings, various depictions of machinery, employees both at work and leisure, floods in 1955 and 1973, and twentieth-century aerial views of the Coatesville plant. Other digital items depict the owning families, company anniversary celebrations, and philanthropic activities supported by Charles Lukens Huston. The collection has not been digitized in its entirety. To view the digitized items online now, click here to visit its page in our Digital Archive.

Post link