#oil drilling

This discovery just goes to show how much we still have to learn about our wonderful oceans!

A big team of scientists publishedtheir findings on April 22, 2016, in the journal ScienceAdvances (you can access the paper for free!). It is quite an astonishing find, as the reef is located in very muddy and polluted waters, but it also stretches over 600 miles!

The reef ranges from depths of 30m to 120m, and consists primarily of sponges and rhodoliths (a type of marine algae that resemble coral), rather than corals. Researchers found over 60 species of sponges, 73 species of fish, spiny lobsters, sea stars, hydroids, and other marine organisms.

Reef ecosystems are known to thrive in very clear and shallow water, with plenty of sunlight and oxygen flow, with stable salinity conditions and low nutrients.

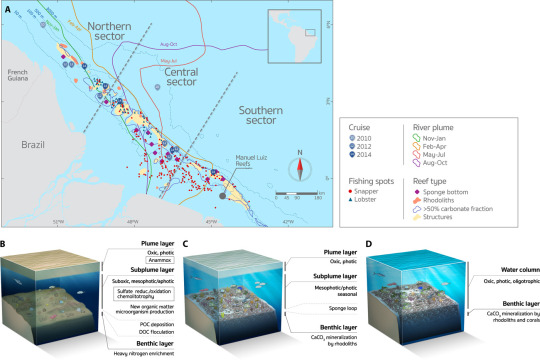

This reef is somehow thriving right below the freshwater outflow of the Amazon river, where vast quantities of sediments coming down the river are swept to the sea. The muddy plume is even visible from space! On top of that, light is very low and almost non-existent, levels of oxygen are also very poor, and nutrients levels are through the roof (333,000 nutrients per second as it flows).

(Scientists shown with specimens they collected from the newly discovered reef. Photo credit: F. Moraes/Courtesy of Carlos Rezende (UENF) and Fabiano Thompson (UFRJ))

Fabiano Thompson, one of the authors of the paper, told Discovery News,“There were some studies back in the 1950s that suggested the presence of reefs, but none pinpointed the reef bodies, dimensions, locations, and compositions.”

Until this study, nobody really had followed up on these. The researchers were originally primarily focused on sampling the mouth of the Amazon. However, Dr. Moura, primary author of the study, had read an article from the 1970s that mentioned catching reef fish in that location, and he wanted to try to locate the reefs. The team first used multibeam acoustic sampling of the ocean bottom to find the reef and then dredged up samples to confirm the discovery.

They then organized another expedition with a full team and took a Brazilian Navy research vessel back to the site in 2014, when they were able to collect and fully describe the findings for the study.

The video below is provided by Science Advances and shows scientists and marine biologists “sampling the plume, subplume, and reefs off the Amazon river mouth during the NHo Cruzeiro do Sul cruise.”

This paper could provide insight how tropical reefs respond to suboptimal and marginal reef-building conditions, which may become more prevalent with the onset of climate change.

“The paper is not just about the reef itself, but about how the reef community changes as you travel north along the shelf break, in response to how much light it gets seasonally by the movement of the plume,”said Patrica Yager, an associate professor of marine sciences at the University of Georgia.

“In the far south, it gets more light exposure, so many of the animals are more typical reef corals and things that photosynthesize for food. But as you move north, many of those become less abundant, and the reef transitions to sponges and other reef builders that are likely growing on the food that the river plume delivers. So the two systems are intricately linked.”

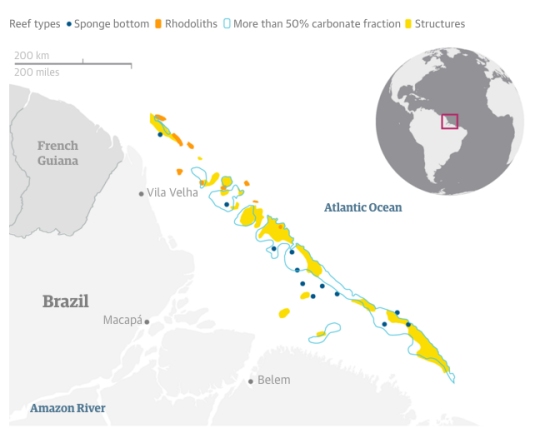

(Map of the Amazon shelf showing the benthic megahabitats and seasonal influence of the river plume. Click here to enlarge)

Sadly,this location is already threatened. Parts of the area have been sold by the Brazilian government to the petroleum industry in 2013 for oil exploration and drilling. Some exploratory blocks are already producing oil in close proximity to the reef, with many more to come.

As a result, the scientists are calling for further studies of the area in order to properly map its marine life diversity, as they have only sampled about 10-20% of it.

Total Begins its Deepest Drilling Project

By: MarEx

Total has commenced an intensive drilling program for the Egina offshore project in Nigeria. Two rigs will be kept busy for a total of 3,000 days, drilling 44 wells in water depths ranging between 1,400 and 1,700 meters.

“This is the deepest offshore project ever operated by Total,” said Jean-Michel Guy, Executive General Manager of the Egina Project. “With production of 200,000…

What Obamas Drilling Bans Mean For Alaska and the Arctic:

President Barack Obama has effectively banned oil exploration, at least for the time being, on some 22 million acres of federal land and waters in Alaska: 12 million acres on land in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), and 10 million acres offshore in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

The policy, announced last week, won’t have much effect on the nation’s oil production—Alaska accounts for only 7 percent of it, and most of the protected areas have been off-limits to industry for decades. And it didn’t really change the status quo or offer anywhere near the environmental protection the President could have conveyed. But he sure ticked off some Alaskans.

Sources: BOEM; USGS; BLM; International Porcupine Caribou Board

In what has become the trademark Texas two-step of its energy policy, the Obama administration compensated the oil industry generously: Braving opposition from marine scientists and environmentalists, it opened up tens of millions of acres off the mid-Atlantic coast and in the Gulf of Mexico to drillers.

That was little consolation to Alaskan politicians, however, who reacted with outrage to the President’s plan. Senator Lisa Murkowski, newly appointed chair of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, called it “a stunning attack on our sovereignty.”

The only bit of good news for Alaskans who see an expansion of the oil and gas industry as the key to the state’s future came late in the week. Royal Dutch Shell said it plans to resume exploratory drilling in the Chukchi Sea this summer, after a three-year hiatus prompted in part by one of its drill rigs running aground in the Aleutians.

Alaska Needs Money

Other countries are moving more aggressively to develop their Arctic resources. Norway recently announced that it would open more areas for drilling in the Barents Sea, where the world’s northernmost drilling platform is scheduled to begin production this summer in the Goliat field.

The current northernmost platform, Russia’s Prirazlomnoye rig in the Pechora Sea, was the target of Greenpeace protests in 2012 and 2013—but in 2014 it produced 300,000 tons of oil. Gazprom, the rig’s owner, plans to drill four more wells on the field this year.

Despite the plunging ruble and international sanctions, Russia is also moving forward on multibillion-dollar projects on the Yamal Peninsula, including a year-round deepwater port and liquefied natural gas (LNG) production plant to export the Arctic peninsula’s vast gas reserves either to Europe or Asia.

The trend in Alaska is in the other direction. Oil production began at Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope in 1977 and peaked in the 1980s, when Alaska produced a quarter of U.S. oil. Prudhoe’s production has lately been declining at close to 10 percent a year, says David Houseknecht, a research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, which estimates oil reserves in Alaska and elsewhere.

Though nearly twice the size of Texas, Alaska has fewer residents (735,000) than Charlotte, North Carolina, and they pay no income tax or sales tax. More than 90 percent of the state’s revenue comes from taxes on oil and gas infrastructure and the oil flowing through the Trans-Alaska Pipeline—which is now a third of what it was at its peak. “You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to do the math,” Houseknecht says.

Declining production on the North Slope and the low price of oil has left the state with a $3.5 billion budget deficit, forcing it to spend $10 million a day from its savings just to make ends meet.

As a result, Alaska officials are highly motivated to open new areas to oil exploration. They’ve gone so far as to file suit to force the U.S. Department of the Interior to fallow a state-sponsored seismic survey of the Arctic refuge’s wildlife-rich coastal plain—the subject of ferocious political battles since the refuge was established in 1980—to assess its oil and gas potential.

Still a Refuge

The Obama administration proposed last week to designate an additional 12 million acres in the ANWR, including the coastal plain, as permanent wilderness area. More than seven million acres of the refuge are already wilderness; the administration wants to designate nearly all the rest.

Only Congress can designate wilderness areas, and with both chambers now under Republican control, such a vote is unlikely. But the move by the administration means the area will be managed as wilderness until Congress or another administration changes course.

The President could have chosen to protect the region permanently as a national monument under the 1906 Antiquities Act, without congressional approval. He did not do so.

Data from the last seismic survey done in the ANWR in the early 1980s suggest the region potentially contains some ten billion barrels of recoverable oil, says Houseknecht—enough to meet U.S. demand for about a year and a half. But the uncertainty is large. In 2002, estimates of the recoverable oil in the vast National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA), to the west of Prudhoe Bay, were also more than ten billion barrels. That estimate fell by 90 percent in 2010 after exploratory wells found mostly gas.

Only one exploratory well has been drilled in the ANWR, on land owned by the village of Kaktovik. Drilled in the mid-1980s by a consortium of companies led by Chevron, the well was a “tight hole,” meaning the results were a company secret and not released to the public. Due to the controversy around the well, it became the tightest hole on the Slope. But during reporting for a story on the NPRA in 2006, I tracked down several sources who had direct access to the well data. Speaking on condition of anonymity, all confirmed that aside from a layer of gas hydrate, the well was a dry hole.

Instead of opening up the ANWR to more surveying and drilling, the Obama administration has reaffirmed the policy of keeping it a refuge from such activity. “We’re thrilled that the President recognized the value of the Arctic refuge,” says Nicole Whittington-Evans, the Wilderness Society’s Alaska regional director. “It’s a national treasure, important for millions of migratory birds, nesting polar bears, and the porcupine caribou herd that local communities depend on for subsistence.

"But we don’t agree that the Arctic Ocean should remain in the five-year leasing plan. It cannot be done safely. The areas that have been withdrawn remain at risk if development moves forward.”

The Action Is Offshore

Despite the controversy over the ANWR, it’s the offshore waters that are believed to contain the vast majority of the 30 billion barrels of recoverable oil and 180 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas estimated to remain in arctic Alaska.

Although the President needs Congress to designate a wilderness, the administration has complete authority over drilling leases in federal waters. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s decision to exclude five areas totaling nearly ten million acres in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas from its 2017-2022 lease sale effectively makes them no-drill zones—until and unless a new administration changes that decision. A month ago the BOEM similarly decided to extend a drilling ban in Bristol Bay, on the south coast of Alaska, to protect the legendary salmon fishery there.

Of the five areas closed to drilling off the north coast, only one is new. Three of the closed areas have been off-limits for decades; they lie off the coast of Kaktovik and Barrow and are prime hunting areas for bowhead whales. A fourth, a coastal corridor extending out 25 miles (40 kilometers) between Barrow and Point Hope, was also excluded from the last round of leasing. If ship traffic is restricted in that corridor, it could impact oil exploration elsewhere.

The newly protected area is a shallow, 30-mile-long (48 kilometers) underwater sandbar in the Chukchi Sea known as Hanna Shoal. Only 50 to 65 feet deep (15 to 20 meters), it swarms with bivalves, crabs, and marine worms that attract thousands of walrus, bearded seals, and other marine mammals that scientists believe are increasingly stressed by sea ice retreat. The shoals are 150 miles (241 kilometers) from where 35,000 walruses hauled out near Point Lay last fall, the largest such gathering ever observed.

The shoals are also less than 30 miles from the exploratory well Shell began drilling in 2012—part their $6 billion bid to tap Alaska’s offshore oil. “Since that area is south of Hanna Shoals and the current is moving northward, anything that spills there could end up on the shoals,” says Kenneth Dunton, a marine scientist at the University of Texas at Austin who has been leading a large, multi-year study of the area.

Most of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas remain open to exploration.

Yet although Shell has announced plans to resume drilling in the Chukchi this summer, pending federal approval, Chevron and Statoil have shelved their offshore Alaska projects, due to the plummeting price of oil and the high cost of Arctic exploration.

Mixed Feelings Locally

Among the Inupiat residents of the North Slope, the question of where drilling should be allowed is a divisive one. They have preferred onshore oil and gas development to offshore rigs that might disturb their cultural lodestone, the bowhead whale. Carefully controlled whale hunts and the sharing of whale meat among families are among the most revered traditions that remain in a culture now rapidly assimilating into the Western world and suffering many of its ills. North Slope communities have one of the highest rates of teen suicides in the world.

Many of the Inupiat, however, are almost wholly dependent on the oil industry for tax revenue and jobs, just like the rest of Alaska. That might be slowly eroding their long-standing opposition to offshore drilling. Last summer, Shell created a joint venture that gives the Inupiat-controlled Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC) and six North Slope villages the option to buy into Shell’s Chukchi Sea leases. ASRC President Rex Rock, Sr., announced the agreement at a press conference with Peter Slaiby, vice president of Shell Alaska.

“The Arctic Slope region is dependent on oil production, regardless of its origin,” said Rock, who is also a whaling captain. He repeated the statement for emphasis.

But Jack Schaefer, mayor of Point Hope, disputes that. The tribal organization in Point Hope joined several environmental groups to challenge Shell’s drilling permits in federal court and the associated environmental impact statement. The court granted a temporary stay until the EIS is amended and new drilling plans are approved.

Schaefer believes the noise from seismic survey activity in the Chukchi Sea over the past decade has already damaged the health of seals and walruses—which affects the Inupiat as well. “The economic and social stress on our community hasn’t changed,” Schaefer says. “We are still 80 percent to 90 percent subsistence, and the walrus, the fish, the seals we depend on are still threatened.”

Post link