#out of africa

A Farm in Africa

(Isak Dinensen hangin’ with Marilyn Monroe and Carson McCullers)

I don’t remember exactly how old I was when I read Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa for the first time, but after that initial encounter, I kept coming back to it. Sometimes I just open to a page and read a passage, like some people read the Bible.

I also read Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women around the same time, and to me, they were all books about women who were readers and writers. They were also books about women who were not at home in their homes: they wanted something else. For a restless teenager in suburban California, this was an appealing concept.

I have lost the copy I read when I was younger, and I am sorry about this. The copy I read now is from 1965: a Vintage Books edition with yellowed pages and a graphic cover in green, yellow, and black. I bought it for 48 cents at Labyrinth Books in New York City, which used to be my local bookstore. I have carried this book with me to countless places. Beaches and mountains. Cafes in foreign cities. One summer day, I read sections of it to my friend’s baby on a blanket at a public pool.

At different times over the years, I’ve marked passages with parentheses and made check marks and stars in the margins. In some cases, I don’t remember why I marked certain things. In others, I do.

It’s a direct and honest book – lyric like a wide, clear sky. But wasn’t until college that I began to understand the first line. I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills. I had understood this to be a statement of ownership. But then, as I reread it over the years, I realized that this line is about loss, nostalgia, and the limits of material ownership. She owned the farm for a period of time, acquiring it by way of a financial transaction, but to own is not the same as to have. She says that she had it because having is something greater than owning, and having is also temporary. You may have something, but you may lose it, too. And she did.

Dinesen also says that she had the farm because she was writing from a later point in her life, when she could see something different than what she saw “high up, near the sun” in Africa. She could see the inevitable encroachment of the past tense. When she leaves Kenya by train at the end of the book, she writes, “The outline of the mountain was slowly smoothed and levelled out by the hand of distance.” The book is levelled out by the hand of distance, too.

When I have moved to new places, I have tried to imagine that I am her, unpacking my boxes. Setting up a life for myself. And when I have had to leave places, I have imagined that I am her, and that one day I will be able to look back on my own lost places with something approaching her understanding.

The opening line inextricably connects her identity to her farm. It is also about Dinesen’s own colonial position, which I did not understand when I was younger and have tried to think though as an adult. She was, in many ways, a product of her time and privilege. Africa was a land of promise for white European colonials, and this is a vision I do not like. But there is more to her story. She was also capable of growth and change, capable of fellowship and friendship with people she was taught to subject. She did not see the world quite like the colonials amongst whom she moved.

The book is really about her relationships with the people on her farm: servants, managers, and guests. Many guests. The film is far more conventional than the book because it foregrounds a romance. Although intoxicatingly beautiful, the film is also flawed, for it can’t imagine a social world that does not structure itself around the relationship between a man and a woman.

Dinesen could imagine far more than the film could. She saw a future for herself away from her family’s Danish estate Rungstedlund, to which she would return. And then, later, she looked at her past with such precision, as if examining the growth of a field of coffee.

A memoir is not about what happened, but about what a writer remembers. It’s a way of reckoning with memory and with what it means to write about your life. And for Dinesen, writing was like dreaming. In dreams, “Great landscapes create themselves, long splendid views, rich and delicate colours, roads, houses, which [the dreamer] has never seen or heard of.” I think she saw herself as created by place. Place was character.

And she had character. She was brave. Dinesen saw herself as a storyteller, which was a way of claiming narrative authority: there may not have been many professional female authors, but women told stories. She had several pen names. She both was, and was not, herself. I didn’t read Simone de Beauvoir until college, during which period I also returned to Out of Africa a number of times. Both writers helped me to figure out my own character.

The word Dinesen comes back to again and again is freedom. She sees the artist as free – as “free of will.” She sees the African night as free. At some moments in her life, she sees herself as free, but it’s a freedom that is circumscribed. It’s a freedom that can’t be sustained. It’s a freedom bound up in a continent that’s being carved up and claimed by the British Empire.

I had a farm in Africa. It is no more.

I’m an English professor at Wake Forest University, where I specialize in Shakespeare and Renaissance literature. My non-academic writing focuses on the intersections between place, objects, and memory. My essays have appeared in Nowhere, Skirt!, 5x5, Artvehicle, Cocktailians,Smoke: A London Peculiar, Airplane Reading, and Open Letters Monthly. My online travel diary Born on a Train, which narrates a long-haul Amtrak trip I undertook in full 1950s dress – complete with hats and vintage luggage – is about nostalgia for old-school train travel.

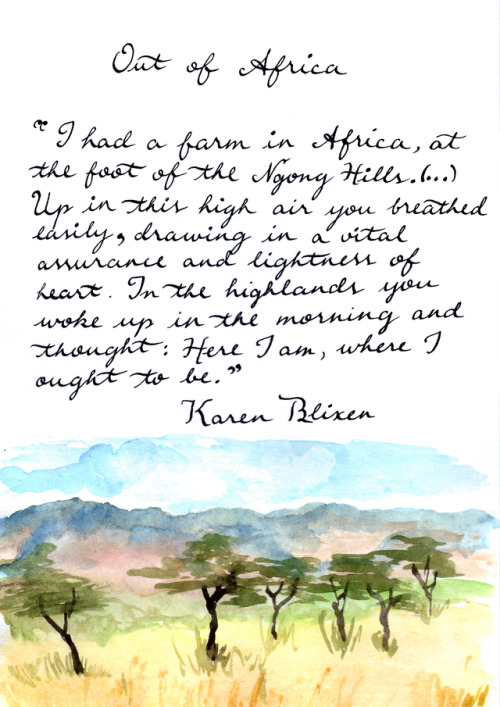

Karen Blixen - Out of Africa

“I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills. (…) Up in this high air you breathed easily, drawing in a vital assurance and lightness of heart. In the highlands you woke up in the morning and thought: Here I am, where I ought to be.”

Post link