#literary mothers

Rachel Wetzsteon, Teacher and Friend

“A toast to depths and surfaces and the lovely rare person who observes and stirs and disturbs them!”—Rachel Wetzsteon from “Notes Toward a Theory of the Self”

It is said that when the student is ready, the teacher appears. In the fall of 1997, I walked, full of trepidation and hope, through the doors of the 92nd Street Y into one of the upstairs classrooms, with its small chairs, toys in primary colors, air redolent with the smell of tempera drying on newsprint, for my first workshop (of what would turn out to be many) at the Unterberg Poetry Center. In a life-altering moment for me, Rachel Wetzsteon appeared. Although it is tempting now, in the wake of her death, to romanticize or mythologize the moment and claim that if not for Rachel, I would never have become a poet, she would not have liked to hear me say that. She would insist that the passion for writing poems was always there and would have somehow found its expression. I can, however, claim with complete certainty that without Rachel as my teacher, mentor and guide, my path into the world of contemporary poetry writing would never have been the same. Rachel showed me, just as she had written of her beloved Auden, “not a room, but a way to light it,/not a goal, but a way of arriving.”

As a poetry teacher, Rachel was generous and perceptive, extraordinarily knowledgeable and well read, imbued with a palpable love of the genre that was infectious and inspiring. It would have been easy, had she been so inclined, for her students to be intimidated by the range and force of her intellect and her formidable credentials. But Rachel’s classroom was never a place for acolytes or affectations—there was, in fact, a sweet humility about her teaching—it was all about poems and their making. Every week she provided interesting readings, challenging assignments and useful comments to student work. She returned our poems covered with question marks, double check marks and memorably trenchant notes in tiny, meticulous handwriting. One such note to me stated, speaking of Auden, as she often was, “better to be Audenesque-ly poignant, than poignantly Audenesque.” I still remind myself of that useful advice.

Although she never ceased being a teacher and mentor to me, over time Rachel became a friend and colleague as well. We shared many experiences: operas, movies, plays, poetry readings, dinners, book parties and occasionally antic car rides to the West Chester poetry conference. She came to my daughter Lucy’s bat mitzvah and was a guest of my family’s in upstate New York and Cape Cod. She never arrived empty-handed: always with books and poems and delightfully idiosyncratic house gifts, often with an animal theme, like the speckled green fish-shaped dish which pleased her because, as she told me, it was not only useful, but it rhymed.

Of all the adventures and experiences I shared with Rachel, the encounters I remember most affectionately were our “poetry dates.” We used to meet at the Starbuck’s on Broadway and 102nd Street for coffee and conversation that generally centered on Rachel’s twin loves: poetry and New York City, two strands which seemed so finely woven together as to be inseparable from her very being. This was not only manifest in her poems (“to know my city/like a bold lover, to trace/its ravishing curves…”) but in her whole persona. When she visited us in Cape Cod, I was not remotely surprised to see her step off the bus in her “urban black” jeans; nor was it entirely unexpected when she wrote her bread and butter note in cinquains, a form I was working in at the time.

It is to celebrate this asphalt-and-poetry aspect of my friendship with Rachel that I include my favorite of her many New York City poems: “Manhattan Triptych” from Sakura Park. Much can be said about this wonderful poem, but to me it perfectly captures the combination of authority and vulnerability so characteristic of Rachel, the poet and the person, who seemed always both part of, and apart from, the urban landscape she traces.

Manhattan Triptych

- i. Café Pertutti

Being here now be damned,

there is a motion in the passersby

that troubles comfort and brings on longing.

Midsummer evening, women drifting by

in peacock colors; what fitter thought

thanWatching them pass, I am happy?

But summer is framed by ardent spring and dense autumn.

Where are they going in their emerald scarves?

- ii. Skater’s Waltz

This was the challenge: not to succumb,

ttat late grey afternoon in Port Authority,

To easy fury at the piped-in music—

such carefree, glittering sound must surround

much happier commutes than mine—

but to let the lushness pierce the grayness,

discover myself gliding in

an indoor rink with all the other skaters.

- iii. Grove Street

Out on a limb, I liked the breezes

but feared the storms. Succeeding days

saw me stubbornly moving through crowds

with wide grin or vacant gaze—two sides

of the same page, for either way I was martini-dry,

incapable of bruising, noticing flecks on necks

rather than eyes, their daggers and their vistas.

And then a tree wept! The petals at my feet…

In fine weather Rachel and I loved to take our poetry dates out doors to any one of the parks that bejewel our Upper West Side neighborhood, and there she will ever remain in my heart and mind—a cherished friend and beloved teacher who perished too soon by her own hand—sitting in a sliver of green, petals at her feet, on a park bench where, as she wrote in “Home and Away,” it is always summer…

Lorna Knowles Blake’s first collection of poems, Permanent Address, won the Richard Snyder Memorial Prize from the Ashland Poetry Press and was published in May 2008. She teaches at the Brewster Ladies Library and serves on the editorial board of Barrow Street, as well as on the Advisory Board of the West Chester Poetry Center. She lives in Cape Cod and New Orleans.

We’re thrilled to rekindle Literary Mothers!

We are so proud to announce that the wonderful Grace Jung will be taking the helm of this ship as guest editor from now until mid-May!

Grace is an accomplished writer, filmmaker, translator and Sunday painter. You can find her website at aechjay.com and on Twitter: @aechjay.

Stay tuned for an essay from Grace on her own literary mother and more regular content. We’ve missed you all dearly.

- Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, Grace Paley

- Conversations with Grace Paley, Gerhard Bach and Blaine, Hall, eds.

- Silences, Tillie Olsen (stumbled across years later at Marfa Book Company, the same shop at which I saw Ms. Paley, and mentioned in the book above.)

When I was maybe twelve, my mom told me that I wasn’t allowed to read her copy of Two Girls, Fat and Thin. I snuck it into my room and stayed up all night so I could finish it in time to put it back in the morning.

There’s the obvious thing about the way Gaitskill writes female sexuality. I used to worry that I was not only a sexual deviant but also the only person in the world whose darkest fantasies didn’t involve touch or even any straightforward kind of conversation.

My first year of art school, I was assigned some stories from Bad Behavior for a class on forbidden love for which we also readLolitaandGiovanni’s Room. I was sexually inexperienced in a way, but I just GOT Bad Behavior because the sex as a stand-in for something else and something else as a stand-in for sex was already so clear to me.

It’s not just a sex thing. Gaitskill’s characters are angry about the same things that I am angry about, and she writes bodies the way I see bodies. My relationship with my body has been so tumultuous and nearly fatal and I’ve moved through some of these sick body moments of my life with a strength that came from rage (vs. hunger or pride).

Her women are hungry: hungry for sex, hungry for pain, stiff from actual stomach hunger.

I don’t think I’ve met many women who aren’t hungry.

The movie version of Secretary was a mess. I actually loved it, but they missed the whole point by making the protagonist overtly mentally ill. That was a shit move, because her sexual deviance ends up pathologized. It’s not like the character in the story isn’t pathological, but it’s subtle. She isn’t seeking out some sort of replacement for the pain she can cause herself, because that pain and the terror of love barely are so unalike.

Recommended Reading: Check out Mirrorball, a story from Don’t Cry. It’s about souls (ghosts?), fucking, and the guy in that one band who will ruin you forever.

I’d recommend all of Don’t Cry. The stories are a little more experimental than her earlier work. I love everything she’s written and would recommend all of her work. Because They Wanted To is a good starting place, maybe. Veronica is stunning. There are a lot of adjectives in Veronica but it doesn’t bother me at all because they all need to be there.

Another good thing to read is this interview of Kim Gordon that Gaitskill did for Interview. I love them together.

Amy Silbergeld is the author of the auto-collaborative novel Rainn (Freke Räihä Förlag, 2014) and the chapbook Rape Joke (Tired Hearts, 2013).

All my life I’ve written, and written reasonably well. Notebooks were filled with work as I documented my world. The passionate shifts of a teenager, the confusion of living within a barely functional family, emotions and experience were all fair game. I painted with words. Then my world changed. My sister died, tragically (are there untragic deaths?), unexpectedly (do we ever really look for it?), young (there is no good age to die). A shock wave set in and

it

rocked

me

hard.

It physiologically altered me, it psychologically altered me, and, worst, it sucked my words into a dark corner that I couldn’t reach. A fetid place opened up in me after my sister died. To even contemplate exploring it hurt. I stopped writing. I stopped seeking beauty, especially in words. I simply existed.

Time passed.

It always does.

Slowly I felt the pressure to write. The desire to put my voice to paper again grew, but my voice was no longer familiar. It was reshaped by the unkind quiet that settled over me after her death. And so I sought a structure in which to learn about who I now was as a writer, a structure that would help me explore the charred landscape inside me. I settled on Stanford’s Certificate Program in Creative Non-Fiction. Toward the end of the program I was assigned a mentor, a respected author who focused on a writer who focused on food.

Anne Zimmerman taught me how to nourish my writerly soul.

Writing the tens of thousands of words that were necessary to meet the requirement established by Stanford was not just a challenge, it was draining. It forced me to return to the death of my sister, and to revisit the suicide of my father. I live in a world where fathers leave and sisters die. I threw myself into examining and writing about how one event fed the other.

Anne read outlines and rough drafts. She read character summaries and walked through timelines. With each successive version that was submitted for review, she found ways for me to wear away callouses that distanced me from the manuscript.

There were days when the words came in an emotional frenzy that left me shaking, prolific in my pain. And there were days when the thought of having to write this story down paralyzed me. Though she had no direct access to the type of loss I was articulating, Anne knew what it was to write from a place that meant something, from a place that was deeply personal. She allowed me to disappear and miss deadlines. To step away from the words and just breathe

She guided me in deeper, and closer to the pain.

She pushed for dialogue and asked for detail.

Anne accepted edits that we both knew were half-hearted and reminded me that even the smallest progress is progress. She taught me that to expose my emotions on a grand scale is not letting the text run away from me. She showed me that being vulnerable is not the equivalent of being weak. She helped me to see that crushingly painful moments can be rendered with grace and beauty.

She refused to allow me to allow myself to fail.

In the end, Anne was as much a midwife as a mother, and the journey she waited for me to complete has left me with a body of work that is an accomplishment bourn as much from my tears as it is from her encouragement. She gave me the space to become reacquainted with my voice. She urged me to shine light on dark places. She let me again imagine the page as a canvas and watched me paint the world with my own hard-earned expression.

Recommended Reading:

- An Extravagant Hunger: The Passionate Years of M.F.K. Fisher by Anne Zimmerman

- M.F.K. Fisher: Musings on Wine and Other Libations by M.F.K. Fisher and Anne Zimmerman

- Love in a Dish … And Other Culinary Delights by M.F.K. Fisher by M.F.K. Fisher and Anne Zimmerman

ANGELA GILES PATEL has had her work appear in The Healing Muse, The Nervous Breakdown and The Manifest-Station. She tweets as @domesticmuse, and when inspired updates her blog. She lives in Massachusetts where she conquers the world, one day at a time.

When “Santa Claus” handed me a present at my father’s annual office

Christmas party, I could tell it was a book. Though books lack a

certain holiday pizzazz, I wasn’t disappointed because I spent most of

my free time with printed copy way too close to my eyes. It was when I

slipped off the wrapping paper that the disappointment came.

The book was titled A Girl From Yamhill and much thicker than what I

was used to reading. Though it was by Beverly Cleary, one of my

favorite authors (I routinely camped out in the sublime corner of the

library where her catalogue and Judy Blume’s collided), it was

subtitledA Memoir. I spent the rest of the party trying to ignore

the book and its butter-yellow cover, framing a black-and-white photo

of a 6-year-old Cleary in an organza party dress. When I accidentally

sat on it, I gave it the stink-eye.

Non-fiction meant schoolwork, the drying out and curing of facts until

nothing remained but a jerky to be gummed and swallowed. A memoir

would surely be the same, with the added torture of recounting the

boring life of someone my great-grandmother’s age.

On the car ride home from the party, I cracked open Yamhill, mostly so

my parents would think I liked the gift.

It begins with Cleary’s oldest memories, snapshots really—her mother

packing her farmer father’s lunch in a tobacco tin, young Beverly

dipping her hands in ink and going “pat-a-pat” all over a white damask

tablecloth.

On the second page, Cleary describes a chilly morning:

Suddenly bells begin to ring, the bells of Yamhill’s three churches

and the fire bell. Mother seizes my hand and begins to run, out of the

house, down the steps, across the muddy barnyard toward the barn where

my father is working. My short legs cannot keep up. I trip, stumble,

and fall, tearing holes in the knees of my long brown cotton

stockings, skinning my knees.

‘You must never, never forget this day as long as you live,’ Mother

tells me as Father comes running out of the barn to meet us.

Years later I asked Mother what was so important about that day when

all the bells in Yamhill rang, the day I was never to forget. She

looked at me in astonishment and said, ‘Why, that was the end of the

First World War.’ I was two years old at the time.

With that, I realized non-fiction wasn’t what I’d thought. Someone’s

life could be interesting, even the mundane parts–after all, wasn’t

that what I was reading about in Blume and Cleary’s fiction ventures?

Drama that was not rooted in mythology and heroic sagas (though they

had a place on my library wishlist too) but in the universal feeling

of inevitable change, in first periods, in fights with one’s mother,

in new schools and old friends, in the dubious mixture of excitement

and apprehension with which children view the future?

From there it was a short leap to realizing my life could be

interesting, if I was willing to observe and faithfully recount and

wasn’t too afraid or too bashful to share pieces of myself. Yamhill

spurred me to start keeping journals, a venture that I remember

largely as revolving around remembering what I ate for breakfast and

recording it. Though the journals were no great success, my worldview

had fundamentally shifted. Sure, no one was going to care about my

preference for Lucky Charms, but someday, I was going to write about

other things that happened to me and someone was going to read my work

and recognize something of herself.

Later in Yamhill, Cleary describes how a poor grade on a lavishly

descriptive essay turned her off from writing description for years.

In a lesson I unknowingly internalized for a very long time, criticism

wounded her but she never let it stop her from writing. I can’t say

for sure what Cleary’s stripped-down, no-nonsense style owes to that

early failure, but I like to think she exhumed the kernel of truth in

that criticism and used it to develop her economy with language, which

she employs like a released arrow: sharp, streamlined and always

focused on a single point.

I never particularly aspired to write “plain” or “to the point”

stories and essays, but several readers have told me they appreciate

those qualities in my work. I will admit to bristling at these

compliments before I remember that “plain” is a code word for writing

like Cleary’s: writing that trusts its story to be big enough,

meaningful enough (no matter how personal or quotidian, as women’s

stories are often labeled) to hook an audience without a sideshow of

technical fireworks.

Despite our rough introduction, A Girl From Yamhill now sits, or

rather, slumps, on my bookshelf with a broken spine, dog-eared pages

and all the other markers of a book well-loved. I have re-read it

regularly over the past 18 years to get another taste of

Depression-era Oregon, to laugh at young Beverly’s exploits and to

read about another woman who knew she wanted to tell her stories and

never wavered in her pursuit of that goal, despite the obstacles. I

will be forever grateful to Beverly Cleary for giving one skeptical

little girl that gift.

Meghan Williams is a writer living in Austin. Her writing,

primarily personal essays, has been featured on The Toast,The Hairpin

andArchipelago.

Wondering why you haven’t seen much from us lately? Unintentional hiatus– other projects gobbled up all our time.

We’re back! In the next few weeks, look for more essays. If you’ve been wanting to shoot something our way but not sure how active we are, send away! Email to [email protected].

In the spring, we’ll launch in full force. Interested in becoming a guest editor for a month or so? Some slots are open, email us!

xox

Nadxieli Nieto & Nina Puro

My Literary Mama

In 1996, I walked into a night class at The New School and I had two things: a musician’s ear and a desire to be a writer. I didn’t understand what either of these things meant to each other, until the instructor demanded we write something and read it aloud. We read. She listened. When we hit a sentence that rang, she stopped, and, in the tradition of her training said, Start there. The first thing I wrote disappointed her.

Victoria Redel was not only discerning, she was beautiful and lively and fun and someone I wanted desperately to please. As I read my first attempt and saw her distaste, I heard instantly how the desire to be a “writer” had overpowered my musician’s ear and I had served up a cliché bowl of mush. That didn’t happen again. Each week there were the exercises; each week, the sound of the work got stronger; each week, she was more pleased. She was kind to me. She said this was the kind of work that could get me get where I wanted to go, an MFA program. She helped. I went.

A decade or so later in my backyard writing my first novel, I struggled once again between my ear and the desire to tell a good story. I had learned from Victoria to listen to the words and let the sound, my ear, determine what came next. It was a poet’s lesson, and I couldn’t make it fit. How could I nail those resonant words down so they could string together a story? I was miles and years from my classes with Victoria. I had no one to turn to for advice. Helpless, I went to my local bookstore in search of an answer.

And there she was: Victoria’s latest novel was a staff pick. I bought it, brought it home and read it that afternoon. There was my mentor’s voice working to strike the same balance between the beauty of words and the needs of a story. In the book, I found permission to bend the rule she had once taught me, and examples of when she found balance and the work sang, and examples of when the balance remained elusive. It was exactly what I needed.

Last year, I read her most recent poetry collection WOMAN WITHOUT UMBRELLA. There, I found a real woman, one I hadn’t gotten to know as a student and admirer. As I read, I saw a heart laid bare. Victoria writes with a unique generosity that imbues all her stories, novels, and poems. Reading this, I realized how mentors work: They are just what we need just when we need them. They are distant enough to allow us to fill them in. We write their story the way we need it to be written so that when they turn their generous attention our way, it gives life to our dreams and we believe achieving them is possible. It is a simple transaction, really. One based not on real knowing, but on wishing. It is a relationship with many forms of communication: classroom instruction, sharing of advice, and the unique gift artists experience when they step into a mentor’s work and find essential lessons and connection.

Sarah Yaw’s novel YOU ARE FREE TO GO (Engine Books, September 2014) was selected by Robin Black as the winner of the 2013 Engine Books Novel Prize. Sarah received an MFA in fiction from Sarah Lawrence College, and is an assistant professor at Cayuga Community College. She lives and writes in Central New York.

I’m not supposed to love her, but her books are my jewel box.

Like many other little girls, I discovered Laura Ingalls Wilder in the library. My school librarian, however, refused to let me check out Little House in the Big Woods, saying I’d be missing out on too many other books more appropriate for my age. My mother gave her a talking to; I devoured the series. My favorite was Farmer Boy, with its extensive descriptions of food so delicious I could eat them off the page, but I also loved Pa’s beard and the tunes from his violin, Laura’s rag doll Charlotte, the blackberry buttons on Ma’s fancy dress, the China Shepherdess, the Whatnot (whatever that was), the sleighs and horses. And I loved the endless descriptions of bed-making and floor-sweeping and butter-churning and well-digging and cabin-building and haystick-twisting. I even loved the coffee grinder used to grind wheat in The Long Winter, and the Pa’s meticulous and endless bullet-making. These were magical objects (looked at longingly, lovingly described) and magical actions, even if I didn’t yet understand what sort of magic they generated.

Once I grew up and became a writer, though, there were so many reasons not to love her: her books had no plot; her Native Americans were stereotypes; her Ma passed along only traditional women’s roles and her Pa used corporal punishment, even if reluctantly; the books were “just” for kids; pioneers destroyed the Western ecosystem; and Laura barely wrote the books herself since they owed so much to her daughter’s editing.

As a serious fiction writer, it was hard to even entertain the possibility that she’d influenced me, but when my daughter was four, I began to read the Little House books aloud to her, and in On the Shores of Silver Lake, I found this passage:

The horse and the man moved together as if they were one animal.

They were beside the wagon only a moment. Then away they went in the smoothest, prettiest run, down into a little hollow and up and away, straight into the blazing round sun on the far edge of the west. The flaming red shirt and the white horse vanished in the blazing golden light.

Laura let out her breath. ‘Oh, Mary! The snow-white horse and the tall, brown man, with such a black head and a bright red shirt! The brown prairie all around—and they rode right into the sun as it was going down. They’ll go on in the sun around the world.’

Mary thought a moment. Then she said, ‘Laura, you know he couldn’t ride into the sun. He’s just riding along on the ground like anybody.’

But Laura did not feel that she had told a lie. What she had said was true too. Somehow that moment when the beautiful, free pony and the wild man rode into the sun would last forever. (Wilder, On the Shores of Silver Lake, p.65)

In it, I greeted myself, not in the character Laura, or the girl Laura Ingalls, or the farm woman and writer Laura Ingalls Wilder with her raising of chickens and her pithy aphorisms and the libertarian politics she probably picked up from her daughter, but as the writer of these particular books, with their focus on object and landscape, their metaphoric and meteoric descriptions, their destitution of traditional plot, their striving for the perfect word and their stretching of language until it becomes a transportive medium all channeled through the character Laura as she voices what she sees, eyes for her blind sister Mary. Losing myself in the magical objects and actions of her books was really losing myself in language, in a process of reading and writing that transported—and still transports—me into another world, a mysterious and thrilling world, tangent to the one I live in.

I knew I would never really play with Charlotte, ride a black pony bareback across the prairie, revel in harvesting hay, or live happily in a homestead shack. It was not the objects or actions themselves that I loved but the reading of them and the writing of them. Their unblinking focus, their yearly swirl through the cycle of seasons, is like looking down a telescope or up from the bottom of a well, like the moment you find yourself face-to-face with the one you love the most and the rest of the world slips away.

During this pure attention, the loved object sucks up the entire world and radiates it back to you, creating a jitteriness that comes from knowing that reading the next word will continue to create the loved one and also start the process of killing the loved one, moving past this most loved image to the next, leaving the loved one in the past.

The objects in books—the objects of books—are so slippery. I do not know if reading and rereading these books as a child formed the sort of writer I’ve become or if they appealed to me because, already at age 7, I was that sort of writer, but each book is a box and each word a jewel.

Maya Sonenberg’s story collections are Cartographies (winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize) and Voices from the Blue Hotel (Chiasmus Press, 2006). More recent fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Web Conjunctions, Hotel Amerika, Fairy Tale Review, New Ohio Review, DIAGRAM, and elsewhere. She teaches in the creative writing program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Literary genealogy can be such a tricky thing. What does it mean to attempt to trace anything as nebulous as literary parentage or forebears? Sometimes it’s a matter of discovering a particular writer’s work that presents a permission to do our own work in a particular way, or even the simple permission to be able to begin to produce our own work at all. Other times, it is far more specific, and far more personal: a mentor, perhaps. This is far easier for some. My early years included a number of encouraging figures, writerly and otherwise, but no-one emerged as the mentor I was so desperately seeking. Early encouragement for my own literary scribblings emerged from Eastern Ontario poets Henry Beissel and Gary Geddes, and later, Ottawa poets Diana Brebner, Marianne Bluger, Mark Frutkin and Michael Dennis, all of whom helped the possibility of my writing more often, but not in any way did they help with the possibilities of the what or even the how. Would these be instead midwifes, or does that confuse these metaphors of literary mothers and fathers?

As we begin to write seriously, most of us seek out examples of writing that by itself encourages, engages and offers something from which we might learn. From the work of Vancouver writer George Bowering, I learned a particular kind of curiosity that expanded out across genres and formal considerations, and a critical and editorial generosity towards others. From San Francisco writer Richard Brautigan, I learned lightness, patience and a particular kind of whimsy. From Toronto poet David Donnell and Winnipeg poet Dennis Cooley, I learned how breath shapes the line, and the line-break. The late Toronto poet bpNichol, among a number of others, helped me learn to be fearless. Still: how do we decide on our particular branches of lineage, and why does it matter? As British writer Jeanette Winterson writes in her memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (Knopf, 2011):

Adopted children are self-invented because we have to be; there is an absence, a void, a question mark at the very beginning of our lives. A crucial part of our story is gone, and violently, like a bomb in the womb.

Self-invented, as Winterson writes. There are important parts of my story still missing, and the mind can’t help but crave something to fill in the gaps. I am constantly seeking. When I look back through my own work there were the traces of permission I received as an early teenager, reading and rereading the highly religious novels of Ralph Connor, pseudonym of the Rev. Dr. Charles William Gordon (September 13, 1860 – October 31, 1937). The son of a Presbyterian minister from Scotland, his novels on my immediate geography gave me a permission to write on and even from our shared landscape of Glengarry County, even through his highly moral and outdated prose, and the contemporary indifference to literature that surrounded my growing up. To read Glengarry School Days (1902) was to engage with specific locations within a mile or two from the McLennan homestead, a century before I had even arrived.

It was most likely after I moved to Ottawa from the farm at nineteen when I discovered the work of Canadian writer Elizabeth Smart (December 27, 1913 – March 4, 1986). I was immediately struck by the lyric and passionate prose of her infamous novel By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945), and began to read as much of her work as I could find, from her two works of prose and the multiple volumes of her journals, to stunning biographical works on her by Rosemary Sullivan and Kim Echlin. Michael Ondaatje even produced a short film on Smart, on her later years in Toronto. It was this, but perhaps more than this. I spent my twenties exploring a number of paths, including as much writing as I could get my hands on, and an exploration of self that I could distinguish from where I had begun, in my rural Ontario space. Some six decades apart, Smart and I were born to the same city, and my attraction to her and her work involved not only her passion but her perseverance, having raised four children solo, abandoned by family and lover, somehow managing to continue writing throughout (although never as much as she wished). Wild and wilful from an early age, she was born to a prominent Ottawa family, and her first novel emerged from the doomed love affair she had with the married British poet George Barker, with whom she had four children, and received not a speck of support (Barker eventually fathered fifteen children with five different women, and never, through the entire process, left his wife). For Elizabeth Smart, it is very easy to let her work be overshadowed by her biography, but to hear the prose of her heart does away with all else. From the opening line of the novel:

I am standing on a corner in Monterey, waiting for the bus to come in, and all the muscles of my will are holding my terror to face the moment I most desire.

My twenties in Ottawa were spent exploring various internal and external spaces, from the library shelves to the late night taverns of this sleepy government town, this capital city. Elizabeth Smart showed through her example that this could be a place from where writing could emerge, even as I saw far too many artistic peers fall into the culture of government service and, whether quickly or eventually, abandon artistic expression altogether. From such an overpowering constraint, only the exceptional emerge: Elizabeth Smart, Tom Green, Paul Anka, Alanis Morissette. There are certainly others, all examples of those who could neither be categorized nor contained. The confines of Ottawa is a geography Elizabeth Smart abandoned early—giving birth to her first child, Georgina, at Pender Harbour, British Columbia, before her decades living in the United Kingdom—away from the interference and absolute judgment of her mother, who would never forgive her for writing and publishing such a scandalous book. Leaving town in the 1930s, she would never return to live in our capital again. When By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept first appeared, her mother managed to convince Canadian officials to seize and destroy what few copies made their way into Canada. Even two decades later, when the book was rediscovered and reprinted, finally making a name for her in both Canada and the United States, her mother renewed her brutal disappointment to Smart in a letter.

Oh, the scandal, the scandal. I loved Elizabeth Smart for being an outcast, and for thriving somehow, despite all the difficulties that came with her relationship with George Barker, as well as her unforgiving mother. I loved her for unapologetically feeling and writing out her passions and romantic fervours, despite what obvious entanglements these caused the whole of her life. I loved Smart for the example of her daring, her grand gestures, and her stubbornness, especially during a period of time that would have harshly judged a single mother raising four children. I loved that she was for a long time the highest paid copywriter in England, well-known for her quick wit, and her quick copy. I loved her for being able to write her own story, and having the willpower to repeatedly get up again, every time someone or something else knocked her down.

This past December would have been her one hundredth birthday, and I’d been months hoping to celebrate her centenary, somehow, but was waylaid through circumstance. Perhaps it was entirely appropriate that I was, my wife and I caught up in the fact of our new daughter’s birth. We were and are distracted and waylaid, and happily so, especially knowing we each have the force of will to return to creative work when we’re able, writing out what we can’t help but write. Elizabeth Smart would certainly understand.

rob mclennan is the author of nearly thirty trade books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction. He won the John Newlove Poetry Award in 2010, the Council for the Arts in Ottawa Mid-Career Award in 2014, and was longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize in 2012. His most recent titles include notes and dispatches: essays (Insomniac press, 2014) and The Uncertainty Principle: stories, (Chaudiere Books, 2014), as well as the forthcoming poetry collection If suppose we are a fragment (BuschekBooks, 2014). An editor and publisher, he runs above/ground press, Chaudiere Books, The Garneau Review(ottawater.com/garneaureview),seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics(ottawater.com/seventeenseconds),Touch the Donkey(touchthedonkey.blogspot.com) and the Ottawa poetry pdf annual ottawater(ottawater.com). He spent the 2007-8 academic year in Edmonton as writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta, and regularly posts reviews, essays, interviews and other notices at robmclennan.blogspot.com

An Open Letter to Alice Munro

Dear Alice,

It seems impossible that you don’t know me. What I mean is that I know your work so well—intimate, is the only way I can describe my relationship to your stories—that I feel like I know you. I consider you a kindred spirit and a teacher. I’ve reread your stories so many times that I know I’ve learned more from them than I have in any writing class. I once spent an entire day deconstructing “Friend of My Youth,” diagramming its structure, its story within a story within a story, to try to understand how you pulled it off. When you won the Nobel Prize, I actually cried with joy. And all day, after the Nobel committee made the announcement, friends emailed and called and texted: “You must be so happy that Alice Munro won!” My adoration of you is so well documented that people were congratulating me on your win, as if you were a member of my family.

But I suppose what I’m saying is that you are a member of my family. My literary family. You are my literary mother. You’re the writer I’ve turned to when I needed the solace that only great literature can provide. (When my actual mother was dying, of cancer, it was your stories I read beside her bed. My mother loved your work, too, and near the end, I often read your stories aloud to her.) You’re the writer who taught me how to move around in time in stories—flashing forward and back. You’re the writer who showed me how much can fit into one short story; how a whole life can be compressed and still feel expansive and lived in on the page. You’re the writer who showed me how complex the architecture of a story can be, and how the motif of storytelling can recur again and again and still feel new. How women and their relationships—to their own desires, and with men, with other women, with friends, lovers, and mothers—can be infinitely compelling. How stories set in small town Ontario (and sometimes in Vancouver) can feel universal. You make it look so easy, with your mastery of suspense, your wry humor, your psychological precision, your brilliant endings. And your stories are full of letters, so it seems fitting that I am writing to you. You’ve said that you think of stories as houses, with various rooms. I’ve entered those rooms and come out dazed. I always go back in. Your stories stick with me; they resonate as if they were actual memories. I know that a minister never slid a hand down my underwear on a train, but I’ve lived inside “Wild Swans” so many times that I feel like it happened to me.

Oh, Alice. If we met, I feel certain we would be friends. That sounds silly, I know. Last summer, when Charles McGrath profiled you in the New York Times, the article included a slideshow of your house in Ontario. I studied the picture of your humble writing desk. It was not unlike what I had imagined. And yet, I felt strange looking at it. Part of me didn’t want to know where you work—I just want the stories to speak for themselves; part of me was devastated to know that you’re retiring, that you won’t be sitting in that chair to write any new stories.

You and I were in the same room once. Deborah Triesman interviewed you on stage at the New Yorker festival a few years ago. I was in the audience at the Directors’ Guild on 57th Street, and I even got up the nerve to ask a question during the Q&A. I asked about your titles; I wondered at what stage in your process you come up with them. We made eye contact. You looked at me as you answered my question. To be honest, I don’t remember what you said. I was too excited and nervous in your presence.

I have copies of all your books. Actually, I have multiple copies of most of them. Sometimes, while traveling, I have an urge to reread a particular story of yours and will go and buy the collection that contains it, even though I already have the same book at home. I always travel with at least one of your books because you are the writer I most like to reread. Your stories have kept me company in places all over the world. The collections I’ve returned to most are Friend of My Youth; Open Secrets; The Love of a Good Woman; Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage; andRunaway.

I’m not in the habit of gushing. Friends rely on me for my critical eye, my cool intellect, not for my unbridled enthusiasm. I’m a reluctant user of exclamation points. But for years I’ve wanted to write to you, to say thank you. Thank you! Your stories, Alice, have meant so much to me. Cynthia Ozick once described you as “our Chekhov.” (I love Chekhov—I return to his work again and again, too.) When Ozick said “our,” I suppose she meant our era, our time. But I understand her impulse to use the possessive pronoun. Those of us who love your work do feel possessive of it. Your stories provide deeply private pleasures. You are ourwriter, part of our family. Now that you’ve won the Nobel, even more people have joined our ranks. And I’m glad to know that your work is finding new fans. But I also want you to know that some of us have loved you for a long time. Some of us are writing stories because of you.

Yours sincerely,

Elliott Holt

Elliott Holt’s short fiction and essays have appeared in the New York Times, Virginia Quarterly Review, Kenyon Review online, Bellevue Literary Review, The Millions, and in the 2011 Pushcart Prize anthology. Her first novel, You Are One of Them (Penguin Press, 2013), was aNew York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, longlisted for the Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize from the Center for Fiction, and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle’s inaugural John Leonard Award for a first book.

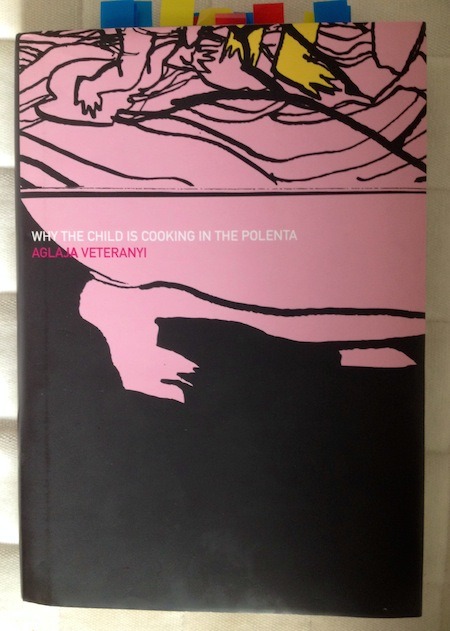

Our story sounds different every time my mother tells it.—Aglaja Veteranyi, Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta

My literary fathers tend to stick around. The late Gabriel Garcia Marquez lived a long, wild life, even if it ended in unjust and heartbreaking—yet poetic, inevitable—dementia. My literary mothers die untimely and tragic deaths.

Unless, of course, they’re Toni Morrison. But Toni is mother to us all; I can’t claim her for myself. She is the grand matriarch who refuses to lay down with every single word.

Yes, I have many mothers, but still I am waiting on my mother to come back for me. You—some of you few unlucky orphans—know this feeling. Having many literary mothers is a little like being raised by wolves. Having many mothers means you still nurse when the first mother looks away. Or when her body is scavenged by lesser animals, many of them inside of her.

My literary mother Angela Carter wrote her final novel after being diagnosed with cancer. Leaving behind a small son and husband, she still made a party of words. She wanted us to remember “What a joy it is to dance and sing!” In fact Wise Children—full of birthdays and babies and twins and magic and Shakespeare and Carnival—ends in incest between a seventy-five-year-old and her hundred-year-old uncle. What a way to go out, Angela. Mom, white-wine drunk again.

But I want to tell you today about my mother Aglaja Veteranyi, whom you probably never heard of, and who drowned herself in 2002 in Lake Zurich. A Swiss writer of Romanian origin, Veteranyi was part of a touring circus. Her stepfather was a clown and her mother an acrobat. She, herself, was made to juggle and dance. This is the subject of the novel Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta, which she published before she took her own life (other works were released posthumously).

My mother Aglaja is a child, herself. My mother is waiting for her own mother to return, because she has been abandoned at an orphanage. My mother Aglaja feels that “home is nowhere, betrayal is everywhere,” (195). She yearns for her mother’s polenta, which, in her native Romanian, mamaliga, translates roughly to “mother’s home cooking,” (197). Yet some part of her fighting for survival knows that to eat mamaliga is to eat poison. This, too, is how I know Aglaja is my mother.

The family was not Rom, but they were wanderers and outcasts, having fled poverty, austerity, and an illiterate Romanian dictator in 1967. The child narrator in Polenta feels dislocated because “Here [in this new place] everybody has warm water in their bathroom and a refrigerator in their heart,” (123). She understands that God is sad because he, too, is a foreigner. “Out of love for poor suffering humanity, God will eat polenta. He’s a foreigner himself, traveling from country to country. He’s sad because he has to start out on a long journey again,” (178).

WithPolenta, there is no dilution of Aglaja’s experience. Vincent Kling notes in his exquisite afterward, having had the vision to translate the work into English, that she is never detached. He explains that Aglaja’s voice offers the “adult retrospective viewpoint but at the same time the child’s passage through successive stages of awareness.” Every line is touching, funny, or pained. Everything is true. Always, she is with us.

I want to tell you about Aglaja Veteranyi because I read Polenta in a single sitting. I read this book looking up at Aglaja and thinking, how will I ever wear your clothes? I read this book thinking, Are you My Mother? I read this book thinking, You Can Be Nobody’s Mother. I read this and stopped every few sentences to write something. I read this believing that everybody should read this. I read this and felt afraid. I read this and thought of all those stories of the old witch who fattens children up to eat them. I read this and felt rage at not knowing the good-enough mother. I read this and thought how you can make a mother out of words. I read this and mourned because words are not always enough, not always. I read this and could not stop reading. I read this and knew what I wanted to be. I read this and knew where I came from. I read this and wanted to share my mother with you, so she could be your mother, too.

My father died of absence. My mother lives in helplessness. My sister is only my father’s daughter. I’ve grown up little by little. And I don’t want any children.—Aglaja Veteranyi

Recommended reading: Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Verteranyi, Dalkey Archive Press

EXTRA-SPECIAL JULY BONUS: Annie shares her smartypants annotations, saying “I am getting really intrigued by how people map texts (their own and others).”

We agree, and if you’ve any annotations or other visual media to share of your own literary mother (suggestions: altars to said idol, drawings, fan letters, collages, elaborate napkin notes, unsent sexts, autographs, marginalia, hair lockets, hair shirts, star maps, or assorted ephemera), send ‘em in, with or without an essay- we may add it as a regular feature!

Annie Liontas’ debut novel, LET ME EXPLAIN YOU, is forthcoming from Scribner in 2015. She is the recent recipient of a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund to conduct research in Trinidad for her newest work BADEYE, which also received Honorary Mention in the 2013 Dana Awards. Annie will be attending the 2014 Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon, Portugal on an Editor’s Choice Fellowship. Her story “Two Planes in Love” was selected as runner-up in BOMB Magazine’s 2013 Fiction Prize Contest and was published by BOMB in December. Other stories and poems have appeared in Ninth Letter,Night Train, and Lit. She graduated from Syracuse University’s MFA Program, where she was awarded the Creative Writing Department Fellowship and a 2013 Summer Fellowship. In 2003 and 2000 she received the Edna N. Herzberg Prize in Fiction at Rutgers University. Annie served as Editor-in-Chief of SALT HILL from 2012-2013. She co-hosts the TireFire Reading Series in Philly.

A Farm in Africa

(Isak Dinensen hangin’ with Marilyn Monroe and Carson McCullers)

I don’t remember exactly how old I was when I read Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa for the first time, but after that initial encounter, I kept coming back to it. Sometimes I just open to a page and read a passage, like some people read the Bible.

I also read Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women around the same time, and to me, they were all books about women who were readers and writers. They were also books about women who were not at home in their homes: they wanted something else. For a restless teenager in suburban California, this was an appealing concept.

I have lost the copy I read when I was younger, and I am sorry about this. The copy I read now is from 1965: a Vintage Books edition with yellowed pages and a graphic cover in green, yellow, and black. I bought it for 48 cents at Labyrinth Books in New York City, which used to be my local bookstore. I have carried this book with me to countless places. Beaches and mountains. Cafes in foreign cities. One summer day, I read sections of it to my friend’s baby on a blanket at a public pool.

At different times over the years, I’ve marked passages with parentheses and made check marks and stars in the margins. In some cases, I don’t remember why I marked certain things. In others, I do.

It’s a direct and honest book – lyric like a wide, clear sky. But wasn’t until college that I began to understand the first line. I had a farm in Africa, at the foot of the Ngong Hills. I had understood this to be a statement of ownership. But then, as I reread it over the years, I realized that this line is about loss, nostalgia, and the limits of material ownership. She owned the farm for a period of time, acquiring it by way of a financial transaction, but to own is not the same as to have. She says that she had it because having is something greater than owning, and having is also temporary. You may have something, but you may lose it, too. And she did.

Dinesen also says that she had the farm because she was writing from a later point in her life, when she could see something different than what she saw “high up, near the sun” in Africa. She could see the inevitable encroachment of the past tense. When she leaves Kenya by train at the end of the book, she writes, “The outline of the mountain was slowly smoothed and levelled out by the hand of distance.” The book is levelled out by the hand of distance, too.

When I have moved to new places, I have tried to imagine that I am her, unpacking my boxes. Setting up a life for myself. And when I have had to leave places, I have imagined that I am her, and that one day I will be able to look back on my own lost places with something approaching her understanding.

The opening line inextricably connects her identity to her farm. It is also about Dinesen’s own colonial position, which I did not understand when I was younger and have tried to think though as an adult. She was, in many ways, a product of her time and privilege. Africa was a land of promise for white European colonials, and this is a vision I do not like. But there is more to her story. She was also capable of growth and change, capable of fellowship and friendship with people she was taught to subject. She did not see the world quite like the colonials amongst whom she moved.

The book is really about her relationships with the people on her farm: servants, managers, and guests. Many guests. The film is far more conventional than the book because it foregrounds a romance. Although intoxicatingly beautiful, the film is also flawed, for it can’t imagine a social world that does not structure itself around the relationship between a man and a woman.

Dinesen could imagine far more than the film could. She saw a future for herself away from her family’s Danish estate Rungstedlund, to which she would return. And then, later, she looked at her past with such precision, as if examining the growth of a field of coffee.

A memoir is not about what happened, but about what a writer remembers. It’s a way of reckoning with memory and with what it means to write about your life. And for Dinesen, writing was like dreaming. In dreams, “Great landscapes create themselves, long splendid views, rich and delicate colours, roads, houses, which [the dreamer] has never seen or heard of.” I think she saw herself as created by place. Place was character.

And she had character. She was brave. Dinesen saw herself as a storyteller, which was a way of claiming narrative authority: there may not have been many professional female authors, but women told stories. She had several pen names. She both was, and was not, herself. I didn’t read Simone de Beauvoir until college, during which period I also returned to Out of Africa a number of times. Both writers helped me to figure out my own character.

The word Dinesen comes back to again and again is freedom. She sees the artist as free – as “free of will.” She sees the African night as free. At some moments in her life, she sees herself as free, but it’s a freedom that is circumscribed. It’s a freedom that can’t be sustained. It’s a freedom bound up in a continent that’s being carved up and claimed by the British Empire.

I had a farm in Africa. It is no more.

I’m an English professor at Wake Forest University, where I specialize in Shakespeare and Renaissance literature. My non-academic writing focuses on the intersections between place, objects, and memory. My essays have appeared in Nowhere, Skirt!, 5x5, Artvehicle, Cocktailians,Smoke: A London Peculiar, Airplane Reading, and Open Letters Monthly. My online travel diary Born on a Train, which narrates a long-haul Amtrak trip I undertook in full 1950s dress – complete with hats and vintage luggage – is about nostalgia for old-school train travel.