#political polarization

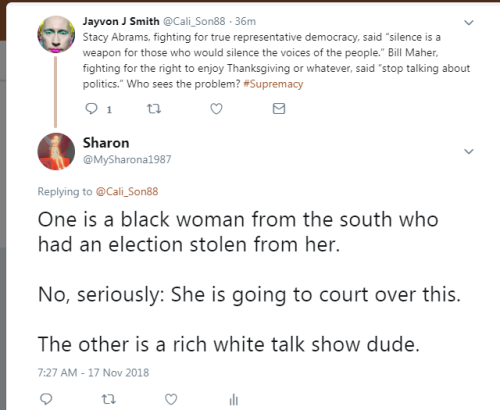

Maher was talking about decreasing polarization (which is a huge problem in American politics) when he said this, not arguing for politics-free turkey.

He’s encouraging people to see each other as humans, rather than walking political pamphlets. And honestly, I’ve found people to be far more empathetic to my views and struggles when they know more about me and my life than my political talking points.

I agree he’s privileged. He certanly doesn’t always have my support. Regardless, the context of what he said is important.

Post link

How to be more spiritually mature and increase world peace at the same time.

If you’re born into a culture in which everybody has a similar worldview, you don’t have an opportunity to develop genuinebelief based on personal experience because your convictions are not subject to scrutiny. Your beliefs aren’t really based on experience or reflection. They are just beliefs (and not necessarily true ones) that you’ve never questioned, and as a result, you’re likely to be very attached to your conviction that they are true. It’s easy to see how this type of belief is common among those who live in societies where people don’t have much of a chance to engage with those who think and believe differently.

In 2019, though, most of us don’t have this excuse for being so attached to our beliefs. There are plenty of people around us who think and believe differently, and we should be reaching out and learning from them.

If you don’t talk to people who hold different views, you will not know what they believe, and you won’t even know what you believe. Having conversations with people who hold beliefs different from yours affords you the opportunity to reflect — and only then can you evaluate whether your beliefs really hold true.

Your beliefs can relate to religion, immigration, spirituality, abortion, gun control, or politics in general, among other things. The seemingly impossible issue du jour is irrelevant. What is relevant: To justify your confidence you must sincerely and peacefully engage people who have solid arguments against your position.

Over the last few years, Americans seem to have convinced themselves that not speaking to people who hold different moral and political beliefs makes us better people — even on college campuses, where intellectual sparring has historically been part of the curricula. However, it does not make us better people. It does make us more attached to our beliefs, less likely to question and revise them, and more likely to convince ourselves that others should believe exactly as we do. Sadly, this seems to have become the norm in the U.S.

Just like what happens in isolated societies, over time, failure to have conversations across divides cultivates a belief myopia that strengthens our views and deepens our divisions. This is bad for us as individuals, and it’s bad for society as a whole.

But for a minute let’s forget about healing political divides, overcoming polarization, or the dangers of mischaracterizing people who hold different beliefs. Reaching out and speaking with someone who has different ideas is beneficial, not for utopian social reasons, but for your own good. This kind of engagement creates an opportunity to reflect upon what you believe and why you believe it. If other greater social goods happen to occur as a byproduct — new, surprising friendships, increased interpersonal understanding, and changed minds on both sides — that’s great. But you have to begin with yourself in order to change the world. World peaces begins with you.

Having conversations across divides isn’t particularly complicated.

1. Figure out why someone believes what they believe. If at all possible, do this in person, not over the internet. The best way to do it is simply to ask politely, “Why do you believe that?” and then listen. Just listen. Don’t tell them why they’re wrong. Don’t “parallel talk” and explain what youbelieve. Figure out their reasons for their belief by asking respectful questions. Then later ask yourself if their conclusions are justified by the rationale they provided.

2. Call out extremists on your side. Identify the authoritarians and fundamentalists who claim to represent your views. Speak bluntly about how they take things too far. This is a way to build trust and signal that you’re not an extremist. (If you can’t figure out how your side goes too far, that may be a sign that you are part of the problem and need to moderate your beliefs.)

3. Let people be wrong. It’s OK if someone doesn’t believe what you believe. Stop being so attached to your beliefs that you think people are evil if they think differently than you. Far more often than not, their beliefs don’t present an existential threat to you — they’re just one person — and you’ll be just fine. Your own beliefs and opinions have probably changed about some things over the years, which can serve as a reminder to hold on to them loosely and allow others to think differently. Don’t even bother to push back or point out holes in their arguments. Do nothing other than listen, learn and let them be wrong, if you still think they’re wrong. Then conclude by thanking them for the conversation. (As a good rule of thumb, the more strongly you disagree with someone’s position, the more important it is to thank them for the discussion and end on a friendly, positive note.)

In our highly polarized environment, talking to those who hold different beliefs isn’t easy, but it is easier than you think. Fewer people talking across divides creates a hunger for honest, sincere conversation. But what there should reallybe is a hunger for truth. And the best way to achieve that is to continuously subject your beliefs to scrutiny. Keep staying open to questioning what you think and believe, and you will get more and more comfortable with allowing others to think and believe differently. You will become more spiritually mature and make the world a better place.

Adapted from Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay

In light of the recent U.S. presidential election and its ongoing aftermath, I thought reposting this might be a good idea.