#race riot

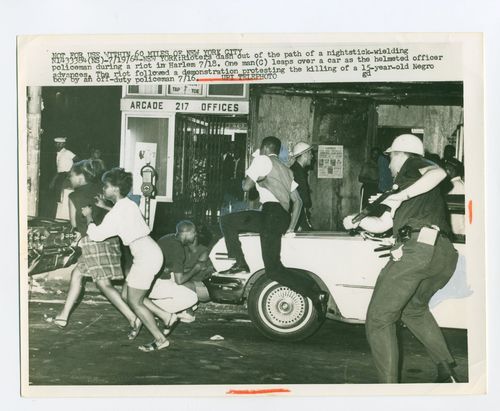

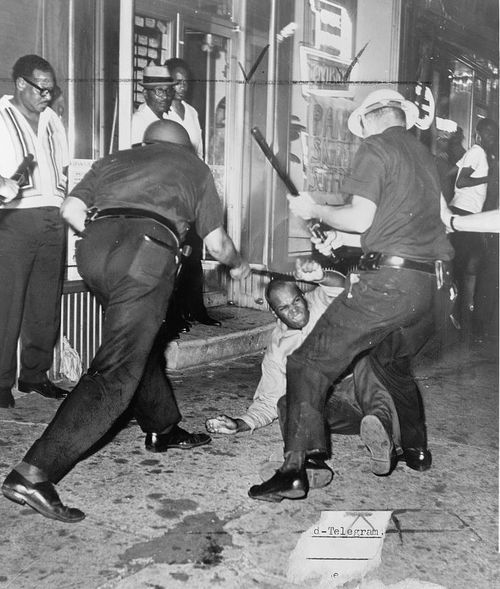

In July 1964, an NYPD officer, Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan shot and killed 15-year-old African American, James Powell, in front of his friends and about a dozen other witnesses. The incident set off six consecutive nights of rioting that affected the New York City neighborhoods of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. The riots left one dead, 118 injured, and more than 450 arrested. The Harlem race riot of 1964 is credited as the precipitating event for riots in July and August in various cities in the US.

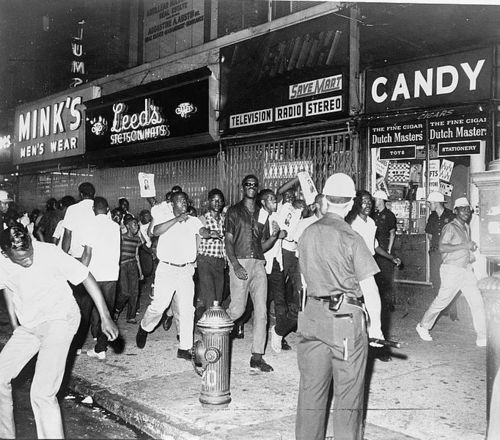

Above: Demonstrators carrying photographs of Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan march on 125th Street near Seventh Ave. during the Harlem Riots of 1964.

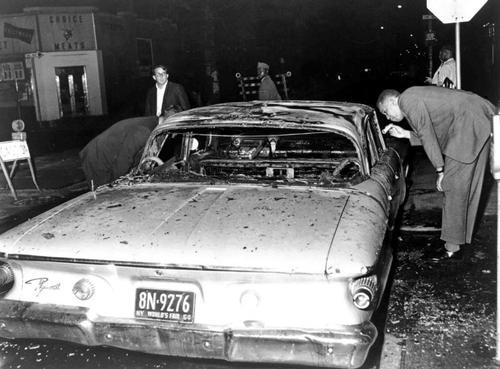

Above: New York police detectives examine the charred remains of a police cruiser, the target of a well-aimed Molotov.

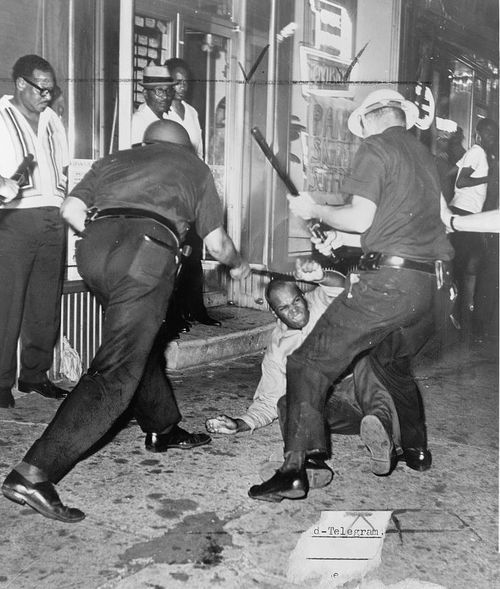

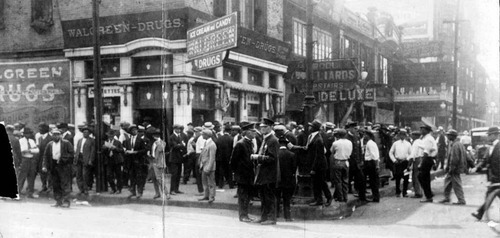

The Chicago race riot of 1919 was a major racial conflict that began in Chicago, Illinois on July 27, 1919 and ended on August 3. During the riot, thirty-eight people died and over five hundred were injured. It is considered the worst of the approximately 25 riots during the Red Summer, so named because of the violence and fatalities across the nation. The combination of prolonged arson, looting, and murder was the worst race rioting in the history of Illinois.

Thousands of African Americans from the South had settled along Chicago’s South Side during the Great Migration. Because the Irish had settled here first, they fiercely protected their neighborhood, political power and jobs which resulted in racial tensions throughout the neighborhood.

On July 27, 1919 the tensions exploded and violence lasted 5 days. At a segregated beach, a white man was throwing rocks that resulted in Eugene William’s death. A white police officer refused to arrest the white man responsible instead arresting a black man. Objections were met by violence.

African-American men gather in front of Walgreen Drugs at 35th and State Streets during the 1919 race riots in Chicago. Police officers stand in front of the crowd.

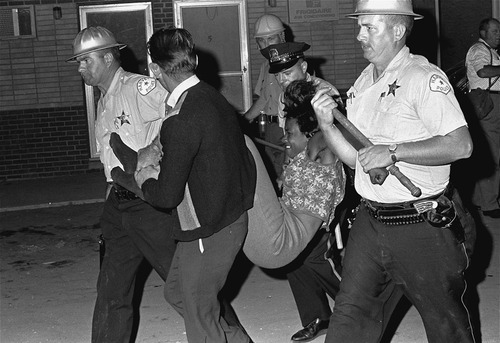

The state militia was called in to quell the violence on the south side of Chicago during the 1919 race riots.

Police remove the body of a black man killed during the 1919 race riots. The five days of violence were sparked when a black teenager crossed an invisible boundary between the waters of the 29th Street beach, known to be reserved for whites, and the 25th Street beach, known to be reserved for blacks.

Troops gather at 47th Street and Wentworth Avenue during the Chicago race riots in 1919.

Black residents of the south side move their belongings with a hand-pulled truck to a safety zone under police protection during the Chicago race riots of 1919.

Many houses in the predominantly white stockyards district were set ablaze during the 1919 race riots. The five days of violence were sparked when a black teenager crossed an invisible boundary between the waters of the 29th Street beach, known to be reserved for whites, and the 25th Street beach, known to be reserved for blacks.

(Photos via the Chicago Tribune. Learn more at Wikipedia)

Photo:Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921.

#OnThisDay in 1921, the deadliest racial massacre in U.S. history occurred in the Greenwood African American district of Tulsa, Oklahoma.This section of Tulsa was a thriving community known as “Black Wall Street’ and included several groceries, two independent newspapers, two movie theaters, nightclubs, and numerous churches.

See our timeline of events leading up to the massacre below.

Roots: 1840-1919

Photo: Photograph of the Cotten family, 1902, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Families of Anita Williams Christopher and David Owen Williams.

In the 1830s the first African Americans came to the Oklahoma Territory with Native Americans along the Trail of Tears. Some were enslaved, and some were free. After Emancipation, they settled throughout the territory and founded several all-black towns. By 1900 African Americans composed 7 percent of the combined Oklahoma and Native American Territories and 5 percent of Tula’s population.

Black Wall Street: 1905

Photo:Photographic print of Eunice Jackson, Owen William and an unidentified woman, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Princetta R. Newman.

Downtown Greenwood was the center of African American life in Tulsa, and one of the first sections of the city that sold to African American settlers. The successful community including several groceries, two independent newspapers, two movie theaters, nightclubs, dozens of businesses, and numerous churches. The thriving community led Booker T. Washington to call Greenwood, “The Negro’s Wall Street” and the moniker stuck.

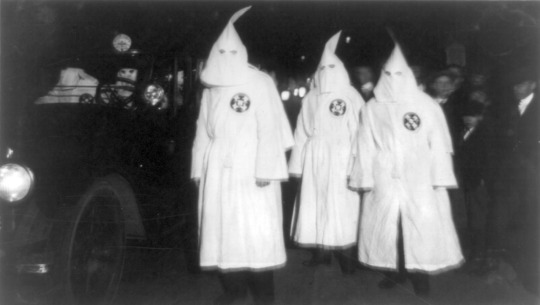

Ku Klux Klan & Race Laws: 1907

Photo: Three Ku Klux Klan members standing beside automobile driven by Klan members at a Ku Klux Klan parade through counties in Northern Virginia bordering on the District of Columbia, 18 March 1922, Library of Congress, National Photo Company Collection.

In 1907 Oklahoma was admitted into the United States, and the legislature immediately began implementing restrictive race laws. By the 1920s many elected officials, law-enforcement authorities, judges, business leaders, and teachers were members of the state’s Ku Klux Klan. Tulsa’s section boasted a woman’s auxiliary and youth chapter.

Oil Fields near Tulsa: 1912

Dubbed the “Oil Capital of the World,” Tulsa experienced booming growth and prosperity during the 1900s. Immigration followed this economic good fortune. African Americans arrived from all over the country, including some from other parts of the Oklahoma Territory.

Veterans in Greenwood: 1919

Photo: “Some of the colored men of the 369th (15th N.Y.) who won the Croix de Guerre for gallantry in action.” Left to right. Front row: Pvt. Ed Williams, Herbert Taylor, Pvt. Leon Fraitor, Pvt. Ralph Hawkins. Back Row: Sgt. H. D. Prinas, Sgt. Dan Strorms, Pvt. Joe Williams, Pvt. Alfred Hanley, and Cpl. T. W. Taylor. 1998 print. Records of the War Department General and Special. Staffs. (165-WW-127-8), 1919, U.S. National Archives.

After returning from Europe at the end of World War 1, many black veterans worked to secure freedom and equality at home. Their efforts alarmed white supremacists, contributing to a growing wave of fear and violence nationwide. Armed black veterans were among the staunchest defenders of Greenwood during the riot.

Tulsa Riots: 1921

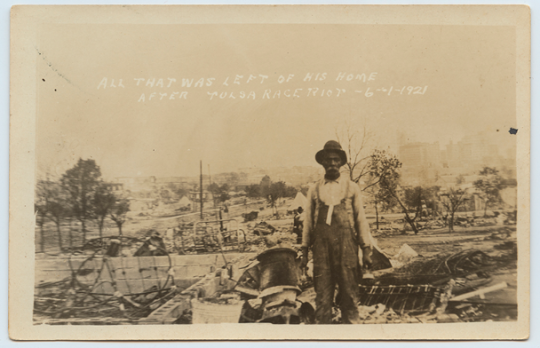

Photo:Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921.

The imprisonment of Dick Rowland, a black man falsely accused of assaulting a white woman, sparked the Tulsa race riot. A lynch mob gathered to hang Rowland, but black Tulsans hurried to the courthouse to protect him. Between May 31 and June 1, 1921, white Ku Klux Klan members and white Tulsans attacked the black residents of Greenwood in a 16 hour race riot. At least 35 city blocks, containing over 1,000 homes, were destroyed by fire. Historians estimate that nearly 300 men, women, and children were killed.

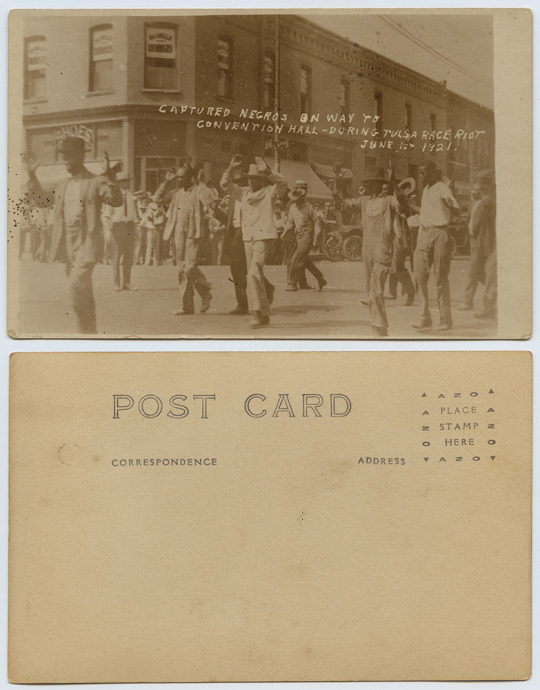

Riot Postcards: 1921 (Post Riots)

Photo: Tulsa Race Riot, June 1st, 1921.

Photo postcards of the Tulsa race riot were widely distributed following the massacre in 1921. Like postcards depicting lynchings, these souvenir cards were powerful declarations of white racial power and control. Decades later, the cards served as evidence for community members working to recover the forgotten history of the riot and secure justice for its victims and their descendants.

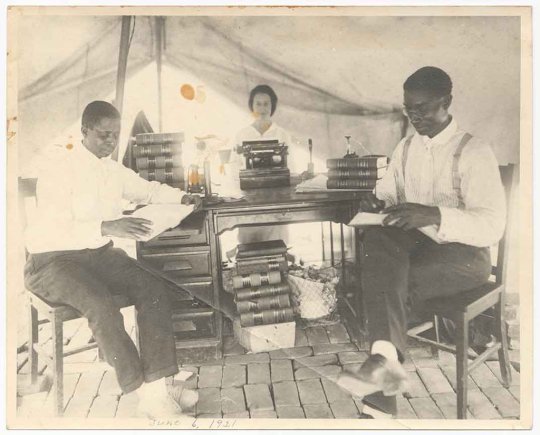

Legacies: 1922-2010

Photo:B.C. Franklin (right) and his partner I.H. Spears practice law with their secretary Effie Thompson on June 6, 1921, in a Red Cross tent five days after the riot.

Dozens of black-owned businesses were rebuilt in Greenwood within a year of the riot, and hundreds more followed over the next three decades. This rapid rebuilding illustrates the energy and resiliency of the community. But the riot’s repercussions—and questions of race, memory, and repair—continue to resonate in Tulsa and across the nation. An interracial movement in the city for education, justice, and reconciliation persists today.