#reblog book club

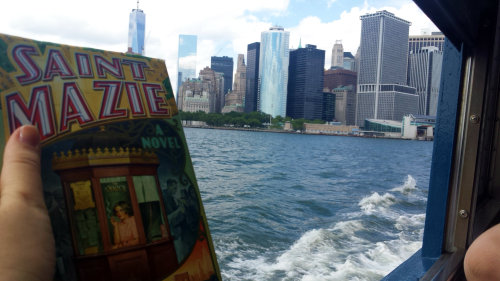

I took Mazie with me on a trip to Staten Island yesterday, and as we were on the ferry going past all of the southern tip of Manhattan, I wondered what she would think of the way the financial district has developed and crept up toward her beloved neighborhoods.

She probably wouldn’t think much of it, if I had to guess.

Post link

I’ve always wanted a sister. I think this is true of every girl who grew up either alone, or with brothers (probably especially, in that case). There was always something so magical about having what seemed like a built-in friend and support system, especially when they were so close in age. As a late-twenty-something now, though, sisterhood doesn’t seem as far as it once did.

In the last couple of years, I’ve been ravenously reading books about sisters and adult women friends, friends whose lives are so enmeshed that they are the family that you create. Books like Rufi Thorpe’s The Girls From Corona Del Mar, Emily Gould’s Friendship, and Kirsty Logan’s The Gracekeepers are all books that spring to mind. Jenny Han’s To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and sequel depend so thoroughly on the three sisters, something so unexpected that I loved.

Thorpe recently wrote a piece for The Toast, “What Writing a Novel Taught Me About Female Friendship,”in which she says:

I was just trying to write about young women by using my own experience, and in my experience, young women have best friends and those relationships are some of the most profound and abidingly meaningful of their lives. But it turned out that speaking about the bond between young women was a cliché. Everyone assured me this was so.

Maybe writing about best friends, or sisters, isn’t about being a cliché. Maybe it is, as Thorpe writes later, about the human condition, what all novels are at some point boiled down to. I think it is.

None of the friendships or sisterships in these books are without tragedy. This furiously complicated and fiercely beautiful relationship relies on a level of tension that only works when there exists a certain push and pull, a quasi-rivalry that is present only in siblings.

And then there’s Jami Attenberg’s Saint Mazie, a book that so purely distills this sister relationship. When I picked up this book, I didn’t know it was significantly about sisters. Sure, it’s about Mazie Phillips-Gordon and the people who knew her. But to me, the pure heart of part one of this book is the relationship of the Phillips sisters, and how they cobbled together their lives in the midst of hard times.

Through everything that happens to them, including finding out that their mother is dying, almost certainly from their father’s abuse, the Phillips sisters hold each other closer, tighter. When they have nothing else, they have each other and the family they’ve created. Rosie, Mazie, and Jeanie are, at the core, all pieces of the same puzzle, no matter how much heartbreak there is between them. Family is always a two-sided coin, though, and the other side holds all of their secrets, everything they keep from each other until it’s no longer possible to hide. And, oh, the secrets they keep.

Attenberg doesn’t write these sisters as a cliché. They’re strong but still second-guess themselves, reckless but mostly well-intentioned, sensible and smart but with moments overtaken by emotion. They’re human. They’re real. Like every set of fully-fleshed women I know or have read about, they hold tight to each other until they can’t. The Phillips sisters held tight until they couldn’t, until Jeanie couldn’t.

But if there’s one thing I know about sisters and family, it’s that they almost always come back, even if it’s not how you expect.

“If Mazie was the wild sister, then Jeanie was the free one.” Wild and free don’t sound so different to me, almost like they were two parts of a whole.