#scotlandsladies

Oil painting on canvas, of Queen Mary of Modena (1658-1718)by studio of Sir Peter Lely (Soest 1618 – London 1680). 1678. A three-quarter-length portrait, almost facing, seated with a dog at her left side, wearing a brownish-red dress and blue cloak; relief of putti, left.

Post link

The Ladies♔Princesses → Isabella Stewart, Duchess of Brittany (1426 - c.1495/99)

Isabella of Scotland was born in 1426 as the second child and daughter of James I and Joan Beaufort. Although there is no details of her childhood, a report before her marriage describes her as being “a well-brought-up young lady, schooled to silence and submission.” By the age of sixteen she married Francis I, Duke of Brittany in front of Bretons and Scottish nobles on 30th October 1442. The marriage appears to have been cordial and the couple had two daughters. In 1450 Francis died and Isabella was pressured by her younger brother James II to return to Scotland, where he had hoped to arrange a second marriage for her. However, Isabella refused, claiming that she was happy and popular in Brittany; along with being too frail to travel. It was more than forty years later, when Isabella died as early as 1495 and as late as 1499, and lived long enough to see the reign of her grandnephew James IV. She was either buried in Nantes or Vannes.

“In both piety and patronages, she could be matched by others in her world. Her life is of interest, nevertheless, because it provides precious evidence of the tastes of one particular woman, shaped by current fashion in devotion. Beneath the splendid trappings and ceremonial routine appropriate for her rank, Isabella attempted an internal pilgrimage as a private soul, a day by day progress on a path to spiritual enlightenment.” — Elizabeth Ewan and Maureen M. Meikle (editors), Women in Scotland c.1100 - c.1750

Post link

The Ladies♔Princesses → Isabella Stewart, Duchess of Brittany (1426 - c.1495/99)

Isabella of Scotland was born in 1426 as the second child and daughter of James I and Joan Beaufort. Although there is no details of her childhood, a report before her marriage describes her as being “a well-brought-up young lady, schooled to silence and submission.” By the age of sixteen she married Francis I, Duke of Brittany in front of Bretons and Scottish nobles on 30th October 1442. The marriage appears to have been cordial and the couple had two daughters. In 1450 Francis died and Isabella was pressured by her younger brother James II to return to Scotland, where he had hoped to arrange a second marriage for her. However, Isabella refused, claiming that she was happy and popular in Brittany; along with being too frail to travel. It was more than forty years later, when Isabella died as early as 1495 and as late as 1499, and lived long enough to see the reign of her grandnephew James IV. She was either buried in Nantes or Vannes.

“In both piety and patronages, she could be matched by others in her world. Her life is of interest, nevertheless, because it provides precious evidence of the tastes of one particular woman, shaped by current fashion in devotion. Beneath the splendid trappings and ceremonial routine appropriate for her rank, Isabella attempted an internal pilgrimage as a private soul, a day by day progress on a path to spiritual enlightenment.” — Elizabeth Ewan and Maureen M. Meikle (editors), Women in Scotland c.1100 - c.1750

Post link

A portrait of Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scots by an unknown artist.

Jane, d. 1445. Queen of James I; daughter of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset

Gallery: Scottish National Portrait Gallery (Print Room)

Date created: Published 1798

Post link

A portrait of Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scots by an unknown artist.

Jane, d. 1445. Queen of James I; daughter of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset

Gallery: Scottish National Portrait Gallery (Print Room)

Date created: Published 1798

Post link

“As messengers, Jacobite Scotswomen personally hand delivered secret correspondence as a safeguard against discovery. After the ‘Forty-five, Jean Cameron of Dungallon (c. 1705-1753?)— wife of the well-known doctor Archibald Cameron of Lochiel, brother of the Gentle Lochiel [XIX Chief of Clan Cameron] and the last Jacobite to be executed for treason in 1753 — was employed by one of the Highland chiefs to transmit messages of intelligence in the area. According to two different sources of enemy intelligence, Jean Cameron, who was living in Strontian, Western Lochaber, was working alongside the younger Clanranald, who had been left behind by those fleeing Scotland, ‘to be at hand to receive such ships and dispatch Expresses with accounts of their news.’ Jean’s job was to carry the intelligence and the ships’ news to a contact in Dounan in Rannoch, who would then forward them to important Jacobite officers such as Cluny and Ardsheal. She was also noted by another government agent, Aeneas McDonnell, as receiving messages from Lochiel. She was requested to deliver them to Jacobites in hiding with the instructions ‘to come to him, but not in a body so as to be taken notice of.’ Although these are the only accounts of Jean Cameron’s role as a messenger, it is quite likely that she was used at other points throughout the ‘Forty-five and it’s aftermath. Using a Highland lady to deliver messages may have been done at this time with the hope that she was less conspicuous and suspicious than a Highlander on the road, who would likely have been searched for weapons, etc., if seen by the frequent Red Coat patrols. This was therefore a precaution against capture and interception; however the acknowledgement of her actions in enemy intelligence reveals that the ploy of using a woman had failed. This could likely be due to an informant or a double agent, of which there were several known at this time and in this region. Yet the success of others could be one reason why little is known about such roles performed by Scotswomen.” — Anita Randell Fairney, “Petticoat patronage": Elite Scotswomen’s Roles, Identity, and Agency in Jacobite Political Affairs, 1688-1766

[Jean Cameron of Dungallon is not to be confused/conflated with Jean Cameron of Glendessary.]

Post link

“As messengers, Jacobite Scotswomen personally hand delivered secret correspondence as a safeguard against discovery. After the ‘Forty-five, Jean Cameron of Dungallon (c. 1705-1753?)— wife of the well-known doctor Archibald Cameron of Lochiel, brother of the Gentle Lochiel [XIX Chief of Clan Cameron] and the last Jacobite to be executed for treason in 1753 — was employed by one of the Highland chiefs to transmit messages of intelligence in the area. According to two different sources of enemy intelligence, Jean Cameron, who was living in Strontian, Western Lochaber, was working alongside the younger Clanranald, who had been left behind by those fleeing Scotland, ‘to be at hand to receive such ships and dispatch Expresses with accounts of their news.’ Jean’s job was to carry the intelligence and the ships’ news to a contact in Dounan in Rannoch, who would then forward them to important Jacobite officers such as Cluny and Ardsheal. She was also noted by another government agent, Aeneas McDonnell, as receiving messages from Lochiel. She was requested to deliver them to Jacobites in hiding with the instructions ‘to come to him, but not in a body so as to be taken notice of.’ Although these are the only accounts of Jean Cameron’s role as a messenger, it is quite likely that she was used at other points throughout the ‘Forty-five and it’s aftermath. Using a Highland lady to deliver messages may have been done at this time with the hope that she was less conspicuous and suspicious than a Highlander on the road, who would likely have been searched for weapons, etc., if seen by the frequent Red Coat patrols. This was therefore a precaution against capture and interception; however the acknowledgement of her actions in enemy intelligence reveals that the ploy of using a woman had failed. This could likely be due to an informant or a double agent, of which there were several known at this time and in this region. Yet the success of others could be one reason why little is known about such roles performed by Scotswomen.” — Anita Randell Fairney, “Petticoat patronage": Elite Scotswomen’s Roles, Identity, and Agency in Jacobite Political Affairs, 1688-1766

[Jean Cameron of Dungallon is not to be confused/conflated with Jean Cameron of Glendessary.]

Post link

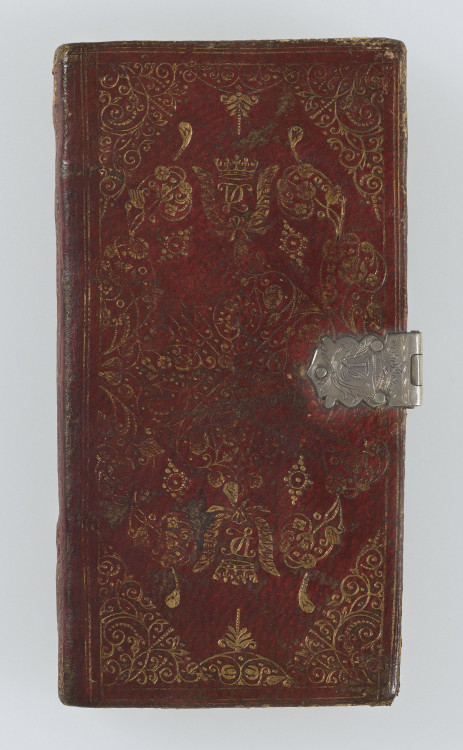

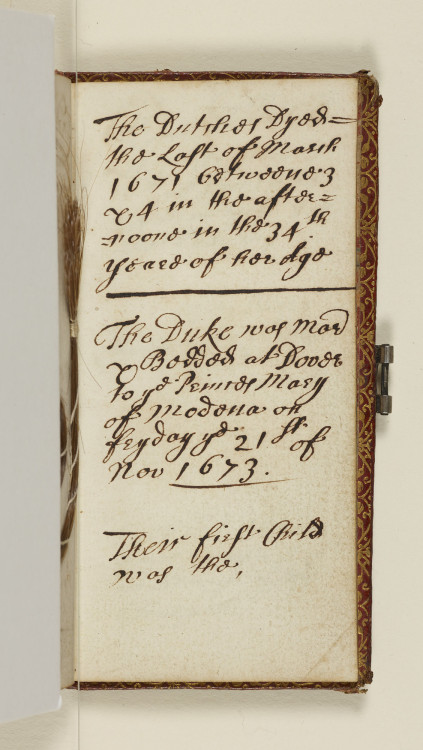

The Births, ages & deaths of Their Royal Highnesses Children. c. 1677-8

This small notebook records the dates and exact times of the births of seven of the eight children of James, Duke of York and Anne Hyde, including the future queens Mary IIandAnne I; their first child, Charles, Duke of Cambridge (1660-1661) is not recorded. The dates and times of the first three children of James and his second wife, Mary of Modena, are also noted. The early deaths of most of James’s children, also recorded in the notebook, vividly captures the high infant mortality rate of the seventeenth century. The death of Anne Hyde at the end of March 1671 is documented, together with a note of James’s second marriage: ‘The Duke was Mar[ried] & Bedded at Dover to ye Princes[s] Mary of Modena on Fryday ye 21st of Nov[ember] 1673’. Opposite, a lock of hair, probably Anne Hyde’s, is sewn onto the page.

The notebook was designed for the Duke of York, whose 'JD’ monogram appears both on the elaborate binding in gold tooling and on the clasps, and though it is not in his handwriting, the presence of locks of hair implies the compiler was very close to the royal ducal family. It was written in one sitting, probably in late 1677 or early 1678, as it records the death of a second Charles, Duke of Cambridge (7 November 1677 – 12 December 1677) but not the birth of James’s next child, Elizabeth, in 1678. It was probably compiled for James’s use; clearly it is a highly personal item.

Post link

The Births, ages & deaths of Their Royal Highnesses Children. c. 1677-8

This small notebook records the dates and exact times of the births of seven of the eight children of James, Duke of York and Anne Hyde, including the future queens Mary IIandAnne I; their first child, Charles, Duke of Cambridge (1660-1661) is not recorded. The dates and times of the first three children of James and his second wife, Mary of Modena, are also noted. The early deaths of most of James’s children, also recorded in the notebook, vividly captures the high infant mortality rate of the seventeenth century. The death of Anne Hyde at the end of March 1671 is documented, together with a note of James’s second marriage: ‘The Duke was Mar[ried] & Bedded at Dover to ye Princes[s] Mary of Modena on Fryday ye 21st of Nov[ember] 1673’. Opposite, a lock of hair, probably Anne Hyde’s, is sewn onto the page.

The notebook was designed for the Duke of York, whose 'JD’ monogram appears both on the elaborate binding in gold tooling and on the clasps, and though it is not in his handwriting, the presence of locks of hair implies the compiler was very close to the royal ducal family. It was written in one sitting, probably in late 1677 or early 1678, as it records the death of a second Charles, Duke of Cambridge (7 November 1677 – 12 December 1677) but not the birth of James’s next child, Elizabeth, in 1678. It was probably compiled for James’s use; clearly it is a highly personal item.

Post link