#medieval history

The Æthelswith Ring, Anglo Saxon England, 9th century AD

from The British Museum

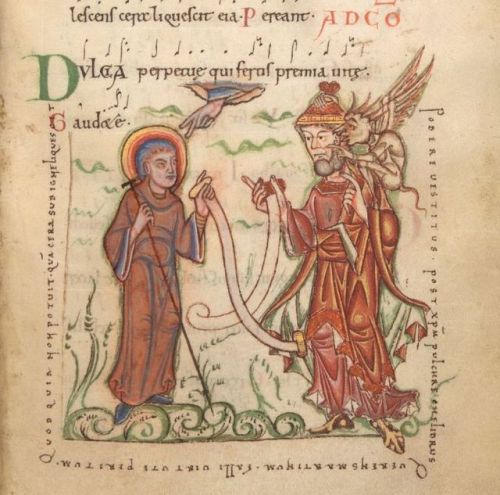

God blessing the animals he created. Look at all the little details, there’s so much talent here!(found in Postilla in Bibliam(Tours - BM - ms. 0052) made by Nicolaus de Lyra in France somewhere around 1500).

Source:

- “Enluminures”(culture.gouv.fr)

Post link

December 1st 1463 saw the death of Mary of Guelders, Wife of King James II.

Mary of Guelders was born circa 1434 at Grave in the Netherlands, she was the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders, and Catherine of Cleves. Catherine was a great-aunt of Henry VIII’s fourth wife Anne of Cleves.

When she was twelve years old, Mary was sent to Brussels to live at the court of her great uncle Phillip, Duke of Burgundy and his wife Isabella of Portugal, where she served as lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Burgundy’s daughter-in-law, Catherine of Valois, the daughter of Charles VII King of France.

Marie, or Mary as she became known in Scotland had been earmarked to marry Charles, Count of Maine, but her father could not pay the dowry. Negotiations for a marriage to James II in July 1447 when a Burgundian envoy went to Scotland and were concluded in September 1448. Philip promised to pay Mary’s dowry, while Isabella paid for her trousseau. Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy settled a dowry of 60,000 crowns on his great-niece and Mary’s dower (given to a wife for her support in the event that she should become widowed) of 10,000 crowns was secured on lands in Strathearn, Athole, Methven, and Linlithgow.

William Crichton, Lord Chancellor of Scotland was sent to Burgundy to escort her back and they landed at Leith on June 18, 1449. Her arrival was described by Chronicler Mathieu d'Escouchy. She first visited the Isle of May and the shrine of St Adrian. Then she came to Leith and rested at the Convent of St Anthony. Both nobles and the common people came to see her as she made her way to Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh.

Marie was 15 and James 19 when the two wed on July 3rd and immediately after the marriage ceremony, Mary was dressed in purple robes and crowned Queen of Scots. Consort by Abbot Patrick.

A sumptuous banquet was given, while the Scottish king gave her several presents. The Queen during her marriage was granted several castles and the income from many lands from James, which made her independently wealthy. In May 1454, she was present at the siege of Blackness Castle and when it resulted in the victory of the king, he gave it to her as a gift. She made several donations to charity, such as when she founded a hospital just outside Edinburgh for the indigent; and to religion, such as when she benefited the Franciscan friars in Scotland. The couple had six children, the oldest James, became James III.

James II died when a cannon exploded at Roxburgh Castle on August 3rd, 1460, before his death he had ordered another castle be built for his wife who was left to oversee it’s construction as a memorial to him, Ravenscraig was still being built when Marie moved into east tower. She also founded Trinity College Kirk in Edinburgh’s Old Town in his memory, she herself died and was buried there in 1483, the old Kirk was demolished, amid protests in 1833 and Marie was interred at Holyrood Abbey.

The pics are of the Queen and their Wedding Feast by Gerard de Nevers

Post link

The Ladies♔Princesses → Isabella Stewart, Duchess of Brittany (1426 - c.1495/99)

Isabella of Scotland was born in 1426 as the second child and daughter of James I and Joan Beaufort. Although there is no details of her childhood, a report before her marriage describes her as being “a well-brought-up young lady, schooled to silence and submission.” By the age of sixteen she married Francis I, Duke of Brittany in front of Bretons and Scottish nobles on 30th October 1442. The marriage appears to have been cordial and the couple had two daughters. In 1450 Francis died and Isabella was pressured by her younger brother James II to return to Scotland, where he had hoped to arrange a second marriage for her. However, Isabella refused, claiming that she was happy and popular in Brittany; along with being too frail to travel. It was more than forty years later, when Isabella died as early as 1495 and as late as 1499, and lived long enough to see the reign of her grandnephew James IV. She was either buried in Nantes or Vannes.

“In both piety and patronages, she could be matched by others in her world. Her life is of interest, nevertheless, because it provides precious evidence of the tastes of one particular woman, shaped by current fashion in devotion. Beneath the splendid trappings and ceremonial routine appropriate for her rank, Isabella attempted an internal pilgrimage as a private soul, a day by day progress on a path to spiritual enlightenment.” — Elizabeth Ewan and Maureen M. Meikle (editors), Women in Scotland c.1100 - c.1750

Post link

Mockumentary set in medieval England with no explanation as to why or how a camera crew is there

A lot of people have mentioned monty python and the holy grail on this post which is accurate but I was envisioning more of a the office/what we do in the shadows type sitcom complete with talking heads and will-they-or-won’t-theys and with the technology that allows the mockumentary genre to exist going completely unquestioned by the entire cast despise it not occurring anywhere else in the otherwise realistically portrayed setting

…hang on, I think there’s a workable premise here.

The camera crew is a team of time-traveling scientists, studying an isolated village. They don’t bother trying to blend in with the locals much, because they know the village will be wiped out by plague in a few years and no trace of their expedition survives in the historical record. The villagers think they’re wealthy-but-eccentric travelers from a distant land, and they’ve bought off the local lord, a minor knight who doesn’t pay much attention to his serfs anyway.

The scientists are jaded. They’ve all been on multiple expeditions to doomed communities, and they’ve learned not to get too attached to their subjects. Part of the mockumentary format includes their video diaries, internal squabbles, and personality conflicts. The rest is interviews with the locals, footage of the crew tagging along with them in their daily lives, and the various experiments members of the crew are running.

(Most of their research is innocuous: water and soil samples, collecting plant and animal specimens to restore future biodiversity, measuring linguistic drift. All their planned human-subject research had to pass an ethics review board.)

(That said, sometimes opportunities for impromptu data collection arise. And sometimes you get bored and want to know what would happen if you projected a 40-foot holographic cow on the road outside the village.)

(The time travel science ethics review board has very clear rules about starting cults: no matter how funny you think it would be, don’t.)

The tone of the show is pitch-black comedy, at least to start with. The crew is burned out and cynical, the villagers are poor and underfed and overworked. Nobody’s doing their best work, or even trying to, really. This is a team that couldn’t get better, sexier, more exciting assignments, and a village full of people whose idea of a better future is a harvest that fails less than last year’s.

But over the course of, say, three seasons — not quite as long as it’s going to take for the plague to arrive — the research team does something they’re really not supposed to do. They get invested. They start to care, a little. They give the villagers a tiny bit of help, here and there — and they’re shocked to see just how much the villagers manage to do with that help.

But the villagers are still doomed, even if they’re clever and curious and likable. Even if a few of them are smart enough to figure out that the research crew aren’t just weird rich foreigners. Even if letting them all die is starting to feel like a waste, or even a crime.

There’s nothing they can do about it. History is very clear about the village’s fate, and they can’t change history.

Right?

Today, I’ll be making a simple barley porridge, as recorded by Ibn Sina (Avicenna) in the 11th century! This dish shares a lot of similarities to my Sumerian Sasqu recipe from a few months ago, suggesting that it may have been a regional dish in antiquity that has been preserved through the centuries to modernity.

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! Check out my Patreon for more!

Ingredients (for about 3 portions)

6 tbsp barley

1l milk

honey

sliced almonds (garnish)

cardamom seeds

Method

1 - Simmer Milk and Soak Barley

To begin with, we need to prepare our barley. Soak about 5 or 6 tablespoons of barley grains in a bowl of water overnight, to help break them down in the cooking process. So if you want to make this today, you should’ve started this yesterday. Or at least 4 hours beforehand. Drain these before using them!

Then, pour about a litre of milk into a saucepan, and set it over a medium high heat. Though the original recipe uses undescribed milk, I’m using whole-fat cow milk. But sheep and goat milk, or even almond milk, can also be used here! In any case, let everything heat up until it is just about bubbling.

2 - Add Barley and Spices

While the milk is bubbling, go de-husk a few tablespoons of cardamom pods - using the seeds themselves in the dish. Keep these seeds aside for later!

When the milk is at a rolling boil, pour in your soaked and drained barley, along with your cardamom seeds.

3 - Serve up

Serve up in a bowl of your choice, garnish with a few scoops of sliced almonds, and dig in while it’s still hot! Add in some honey, to taste, if the dish isn’t to your taste!

The finished dish is a delightfully soft yet fragrant and sweet dish! The barley has broken down slightly into a toothsome paste, and the taste of the cardamom gives the talbina a wonderful floral kick to each mouthful.

The original sources for this dish describe it moreso as comfort food - something that is rarely recorded in medieval cookbooks! Typically, contemporary documents would describe similar dishes, or things that would pair with the recipe in question. However Ibn Sina (Avicenna), along with numerous other contemporary Arabic writers, explicitly states that this dish is not a day-to-day thing, rather one that “relieves some sorrow and grief”

“The talbina gives rest to the heart of the patient and makes it active and relieves some of his sorrow and grief.” [Saheeh al-Bukhaaree (5325)]

Though I used honey here, pureed and stewed dates may have been used as well - which we can see in my earlier sasqu recipe.

11th century Byzantine honey cakes

Today, I’ll be taking a look at a medieval Byzantine honey cake - which itself is based on an earlier Greek iron-age cake, amphiphon. This is going to be a light, fluffy cake with a rich, honey flavour!

In any case, let’s now take a look at the world that was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! If you like what you see, consider supporting me over on Patreon!

Ingredients

1 cup flour

¾ cup butter

¾ cup sugar

½ cup walnuts

salt

orange rind

1 - Cream the Sugar and Butter

To begin with, toss about ¾ of a cup of room-temperature butter into a mixing bowl. Into this, place about ¾ of a cup of sugar. Mix everything together using a wooden spoon, smearing the butter into the sugar along the side of the bowl. Do this until it takes on a rich, creamy texture. At this stage, beat three eggs into the mixture, taking care to mix them all thoroughly before progressing!

2 - Add Dry Ingredients

Next, toss in about a cup’s worth of plain flour, along with a pinch of salt. Mix this together into a smooth batter. If it’s looking a little dry, add a tiny splash of milk to rehydrate it a little.

When the whole thing is combined, and still sticking to the side of the bowl, toss in about a half a cup of roughly crushed walnuts. While it’s stated that walnuts are served alongside this dish, it’s likely that they would have also been baked into the cakes, which help soften the nuts.

3 - Prepare Tin

Using the butter wrapper, grease a baking tin. While metal tins were likely used in late antiquity/the early medieval period, stoneware would have also been widely used! The original recipe doesn’t seem to discuss baking instruments, so I opted for using a shallow square dish.

When it’s been greased sufficiently, grate the rind of an orange into the dish. Though oranges and lemons were seemingly grouped together as “citron” in antiquity, we can assume that cooks would have known the difference between the two. So, I used an orange, as it pairs nicely with the honey and the walnuts here.

4 - Bake

When the tin is prepared, pour your batter into the dish. Make sure it’s spread evenly across it, so it all bakes at the same rate. If you want, you can dust the top of your cake with ground cinnamon. Keep in mind that this will brown faster than your cake will, so it may look burnt in the oven, but really it will only be barely cooked!

Place your tin into the centre of an oven preheated to about 350F or 175C for about a half an hour, or until the edges of your cake have browned and turned crisp!

5 - Finish Cake

Take it out of the oven when it’s done, and let it cool to room temperature. But before it’s fully cooled, pour a good amount of honey over the whole thing! This will let the whole cake become infused with the sweetness of the honey!

When the cake has fully cooled, cut it into segments, and serve up with some walnuts!

The finished cakes are wonderfully light and sweet! The caramelised orange rind on the base gives a wonderful zesty kick to the honey taste. The cake rises a fair bit due to the number of eggs used, but retains a great airy texture.

This week, I’m going to be making a quick and easy rice pudding dessert, recorded in a 14th century Neapolitan cookbook - the Cuoco Napoletano! Rice began being used in medieval Europe intensively around the 9th or 10th centuries AD - though evidence for it’s cultivation in the Eastern Mediterranean date back to Alexander the Great’s conquests into Asia.

In any case, let’s now take a quick look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above!

Ingredients (makes 4 portions)

2 cups rice

4 cups almond milk

1 cup sugar

saffron

Method

1 - Wash and Cook Rice

To begin with, we need to cook some rice. I used basmati rice, but Arborio or other, fatter-grained rice would have been used in antiquity as well! Begin by washing a couple of cups of rice in some cold water. Move the grains around with your hands, to get rid of excess starch. When the water runs clear, place your rice in a pot, and fill up with cold water until the rice is just about submerged.

Place your pot over a high heat until the water boils. Let everything cook until the rice is almost done - but not quite ready. Take it off the heat and let it cool down.

2 - Prepare Saffron

Next, rehydrate your saffron a little. Do this by letting it sit in some boiling water for a few minutes. Saffron is VERY expensive, so you can of course skip this step - it’s really only to add colour, and a slight woody taste - to the finished dish!

3 - Prepare the Milk

While your rice is cooling, go pour about 4 cups of almond milk into a saucepan, along with a cup’s worth of sugar. Bring this to a boil over a medium heat. The original recipe tells you how to make almond milk as well, by combining ground almonds with water. Keep your sugar and milk mixture stirring occasionally, while you wait for it to boil.

4 - Combine Ingredients

When the almond milk is at a rolling boil, turn the heat down to low and let it simmer away. Add in your cooled rice back into the pot, along with your rehydrated saffron! Mix everything together, and let it cook for another ten to twenty minutes. Or until your rice is lovely and soft, and stays in a soft mound when you pile it up with a spoon.

Serve up either warm or at room temperature, and dig in!

The finished dish is quite simple, yet very sweet! The three main ingredients - rice, almonds, and sugar - would have been readily available in many medieval Mediterranean markets - particularly in those markets at the conflux of trade routes, such as along the Italian coast.

The original recipe also mentions that other kinds of milk can be used when making this - such as goat milk. However, it neglects to mention that if you use those kinds of milk, stirring it when it’s coming to a boil could cause curds to form - making it more like a kind of cheese, rather than pudding.

As the autumn comes to a close, and the cold of winter sets in, I figured it’d be a great time to make a simple savoury treat from medieval Georgian cuisine - stuffed apples! Though savoury stuffed apples are commonly found in the Caucasus region, this isn’t exclusive to Georgia! Armenia, and parts of north-western Iran, western Turkey, and Azerbaijan also have regional variants of this dish!

In any case, let’s now take a look at the world that was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! If you like what I make, consider supporting me on Patreon!

Ingredients (for 4 servings)

4 large tart cooking apples

honey

ground cinnamon

ground nutmeg

water

1 cup rice

butter

Method

1 - Prepare Apples

To begin with, we need to prepare our apples. Do this by slicing the top off of about 4 large apples, before carving out the middle - leave about a finger’s width of a wall.

Drizzle some honey in here, and sprinkle a little ground cinnamon inside. Honey was used in the civilisations of the Caucasus for millennia, and was an important part of many people’s diets in the medieval period.

2 - Prepare Filling

Next, pour a cup of rice into a bowl, and pour some water over this. Rinse the grains until the water runs clear. When it’s cleaned, keep the grains just about submerged, and bring the pot to a boil. Cook your rice for a few minutes until they fluff up. When they’re done, let them cool down a bit, before mixing in a handful of raisins or sultanas, along with some freshly-grated cinnamon, and some freshly grated nutmeg, or mace.

Both of these spices were commonly found in the kitchens of the region in the medieval period, thanks to Georgia’s proximity to the silk road and spice trade.

3 - Assemble Stuffed Apples

Take your hollowed apples, and fill them to the brink with your rice stuffing. Place a dollop of butter over this, before placing the lids of your apples back on top.

Place your apples onto a deep tray, and pour about a cup of water into this. If you want, you could add some more aromatics or spices in here - such as mint, rosemary, or cloves! Then put the tray into an oven preheated to 350F or 175C for about a half an hour, or until the apples puff up and turn golden.

Take your apples out, and serve up alongside some roast meat and vegetables! Spoon over some of the baking liquid, to rehydrate the rice a little too!

The apples are quite tart, but with a deliciously sweet undertone. The flesh is melt-in-your-mouth, and pairs very well with the texture of the fluffy rice. This pairs really well with roast lamb and pork, and is a fantastic (and easy) side-dish for any feast you’re preparing for!

This weekend is the pre-Christian Irish holiday of Samhain - celebrated more widely as Halloween! Due to my current circumstances, instead of a recipe this week, I’ll be doing this instead! Pumpkins weren’t present in Ireland until well after the Columbian Exchange, but turnips are an indigenous vegetable here - and were carved for millennia.

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! If you like what I do, consider checking out my Patreon!

Ingredients

A Turnip

Method

1 - Cut top off turnip

To begin making a carved turnip, you of course need a turnip! Try and get a large turnip, as it’ll be more sturdy once carved. Cut the top off the root bulb - alternatively you can cut the base off the turnip, using the leaf bundle at the top as a handle!

Either way, be very careful when cutting into this. Turnips are notoriously difficult to cut easily. Plus, if you’re careless - like I was earlier - the turnip will win against you.

2 - Core turnip

When the top of your turnip has been taken off, start scoring the inside of your turnip with a knife. Leave about a finger’s width of a wall of the turnip. This will make it easier to carve a face out of later, and will also give the whole thing a bit of structure when it’s done.

You may find it easier to use a metal spoon when scraping the inside of your carved turnip - use whatever is easiest for you! But try and not scrape more than your spoon can handle, as it can and will bend to the will of the turnip.

3 - Carve Face

When your turnip is suitably hollow, you can now get to grips with gouging out it’s eyes and mouth. Traditionally, turnips were carved in the image of scowling faces - in an attempt to dissuade evil spirits present at Samhain. But of course, you can carve whatever you want these days! Try and carve some teeth if you want!

When the whole thing has been carved to your liking, place a lit candle inside it, and set it out somewhere for you to enjoy!

Carving vegetables or fruit is found worldwide, throughout various cultures and time periods. While the art of carving turnips for Halloween has fallen out of style due to the ease and hardiness of the pumpkin, turnips are still used around Samhain in rural areas of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales!

The term Jack-o-Lantern is an 18th century name for these decorations, and we are unsure of what they were referred to in antiquity - in Irish it was likely called a carved turnip. A simple name, but it does the job well enough!

This week, I’m going to be recreating a simple carrot and coriander soup that was popular in medieval French cuisine - the simple Potage de Crécy. Although I’m using orange carrots, which were rare in antiquity, carrots, parsnips, or any combination of these would work well here!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! Check out my Patreon for some more recipes!

Ingredients (for 2-3 portions)

1 onion (or an equal volume to the amount of carrots) chopped

3 carrots (or an equal volume to the amount of onions) diced

2 cloves garlic

olive oil

ground coriander

500ml stock (e.g. chicken, vegetable, etc.)

Method

1 - Prepare and Cook Onion

To begin with, we need to peel and chop one whole onion. Onions of all kinds were a staple of most cuisines from the neolothic period to modernity, as they’re hardy, filling vegetables that have a multitude of uses. In any case, chop this into fine chunks, so they cook evenly. When this is done, toss some olive oil into a pot, and heat it up over a medium high heat.

When the oil is shimmering, toss a couple of crushed cloves of garlic into the oil, along with your onions. On top of this, sprinkle some salt, some freshly ground black pepper, and some freshly ground coriander. Put all of this back onto a medium high heat for a few minutes while you deal with your carrots.

2 - Prepare and Cook Carrots

Go peel a few carrots - aim for about an equal amount of carrots to onions. When they’re peeled, slice them into discs - making sure they’re all the same size, so they cook evenly. Although orange carrots were fairly rare in antiquity, they’re the dominant strain today. But remember that throwing in some parsnips or heriloom carrots wouldn’t hurt either!

When your carrots are prepared, add them to your onions when the pot smells lovely and fragrant, and the onions have turned translucent. On top of your carrots and onions, pour about 500ml of a soup stock of your choice. I went with chicken stock here, to add a more meaty background taste, but any stock would work well enough here!

3 - Cook

Place your pot over a high heat, and let it come to a boil. When it hits a rolling boil, turn the heat down to low and let it simmer away for about 30 minutes, or until a knife, when stabbed into a piece of carrot, comes out easily.

Serve up in a bowl of your choice, garnish with a little sprig of parsley or cilantro, and dig in!

The finished soup is rather sweet, thanks to the carrots and onions, and has a lovely zesty taste thanks to the coriander. The broth thickened up nicely, and the carrot chunks softened into a toothsome mouthful.

This week, I’ll be taking a look at another medieval Syrian dish - this time, a simple pistachio sauce chicken bake! It’s a sweet and savoury take on a staple of near eastern cuisine at the time - fitting for most people in the medieval period to be able to make!

As with a few other recipes like this, many thanks to Charles Perry’s translations from the original Arabic textbooks!

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! If you like what I make, please consider supporting me over on Patreon!

Ingredients

250g chicken (any cut of meat)

300g pistachios

salt

pepper

ground cumin

ground coriander

honey

Method

1 - Season Chicken and Bake

To begin with, we need to prepare our chicken. Do this by cutting your cuts of meat with a knife, before seasoning your cuts with equal amounts of salt, pepper, ground cumin, and ground coriander. The original recipe doesn’t make note of any spices, but we can infer from elsewhere in the cookbook that cumin and coriander formed the core of medieval Syrian cuisine. So, season this liberally! When this is done, place your chicken onto a lightly greased pan, and then into the centre of an oven preheated to 180C for about 20 minutes. While this is cooking, go prepare your pistachios!

2 - Grind Pistachios, Make Sauce

Next, shell 300g worth of pistachios. This will result in a significantly lighter amount of shelled nuts, but this is suitable for about two or three portions of meat.

In any case, when they’re shelled, go crush them into a fine powder in a mortar and pestle. Try and go for a very fine sandy texture.

When these have been ground up, toss them into a pot, along with a tablespoon or two of honey, as well as a small splash of water if everything looks too dry. Put all of this over a medium heat, and let it cook away until the honey softens and bubbles. Keep it stirring, so the honey doesn’t burn onto the bottom of the pot. This should only take about 15 minutes to cook - if the sauce starts looking a little brown, quickly take it off the heat so it doesn’t burn. It’s safer to do this slow and low, rather than fast and high.

3 - Assemble Dish

When the chicken and the sauce is done, pour a generous amount of the sauce onto a plate, before arranging your chicken on top. Garnish with a few whole pistachios, and a few sprigs of parsley, and dig in!

The finished dish is a succulent and sweet meal, with a wonderful floral sensation from the spices. The original recipe claims the chicken should be cooked in the sauce itself. This could be done, but you’d probably need more sauce than I’ve made here - it would result in a cut of meat that was tenderly stewed, with the seasoning leeching out into the pistachio and honey sauce. I opted for preparing these separately, as it was more sanitary to do on the day. It’s just as likely that it was prepared like this in the medieval period as well, but was not recorded in the original text.

Today, I’m going to be recreating a recipe for a German apple pie from the Registrum Coquine - the contents of which are suited for a middle-class palette of medieval European world

In any case, let’s now take a look at The World That Was! Follow along with my YouTube video, above! Consider supporting me on Patreon if you like my recipes!

Ingredients

6 apples

2 cups flour

water

butter (or oil)

ground cinnamon

ground nutmeg

cloves (either whole or ground)

honey (if the apples are too tart)

Method

1 - Peel and Chop Apples

To begin making an apple pie, we need apples. Though the original recipe doesn’t state any particular apples, tart apples tend to make the best filling. Peel your apples, and chop them into fairly evenly-sized chunks so they cook evenly. I found that about 6 apples suited a pie fit for about four people.

2 - Prepare the Filling

When your apples are chopped, go toss some butter (or oil) into a pot, and let it melt. When it’s foaming, toss in your freshly-grated nutmeg, cinnamon, and a few cloves, and stir them around so they’re all covered in hot butter. You can, of course, crush your cloves, but I enjoy the sensation of biting into a whole clove - it’s up to you!

When your spices have cooked a little, toss in your chopped apples! Stir everything around so they’re all covered in butter and let it all cook away over a medium heat for a few minutes - until they soften and turn golden. At this point, take them off the heat and let them rest while you make your dough.

3 - Make Pie Dough

Since the original recipe assumes people know how to do this, we’re going to be using a cup or two of plain flour mixed with a little water. Add it little by little until it comes together into a cohesive dough. Knead this together until it’s smooth, and roll out using a rolling pin. Do this twice - once for the base of the pie, and twice for the lid. Roll the dough out fairly thin, as the whole pie won’t be baked for too long.

Pour some olive oil (or butter) into a pie dish, and stretch your pie dough over it, tamping it down with your knuckles into the corners.

4 - Assemble Pie

Pour the cooked apples into your pie dish, spreading it out evenly. When this is done, place your other circle of dough over the top. Crimp the edges of the two discs of dough together - it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t look too pretty! It’ll bake wonderfully, and taste delicious either way!

When your pie is ready, toss the whole thing into the centre of an oven preheated to about 180°C/356°F for about 25 minutes!

When the pie is done, take it out of the oven to cool down to room temperature before dividing up and digging in! Drizzle some honey over the slice you’re eating to really amplify it’s texture!

The finished pie is delicious and sweet, the spices forming a lovely warming sensation with each bite. The texture of the cooked apples is practically melt-in-your-mouth, and contrasts with the pie crust! As a side note, the pie crust itself - once cool - is rather tough. However the crust on the base of the pie is soaked in the juice from the apples during the cooking process, and is a much more palatable part of the pie. If I were to make this again, I’d either omit the top lid of the pie, or remove it before serving.