#sound recording

His name in the credits is as synonymous with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as hearing Leo the Lion roar before a film. Douglas Shearer was MGM’s head sound designer and recording director. By some, Douglas Shearer could simply be reduced to the brother of actress Norma Shearer. He moved to Los Angeles from Canada to join his mother and two sisters (after not seeing them for four years). Norma became not only one of MGM’s movie queens but one of the biggest global stars of the 1930s.

The transition from silent to talking pictures was an uncertain time in Hollywood. Shearer, an engineer by trade, muscled his way in and with his significant inventions, transformed talking pictures and filmmaking. “During his more than 40 years with MGM, he contributed more than any other man in Hollywood to the perfection of motion picture sound,” said writer and filmmaker, Ephraim Katz. But Douglas paved his own way and was conscious of the implications of nepotism. He went so far as living by himself away from his family, making a point that he was not connected to Norma. He didn’t need Norma’s star power, though it probably didn’t hurt in making initial connections.

Shearer’s first job in Hollywood was in the prop room, where he called himself “assistant animal guy,” as he wrangled several pigeons, cows, chickens and pigs, according to film historian Gavin Lambert. While working with the livestock, it was the discussion of sound that peaked Shearer’s interest. He pitched an experiment to MGM of adding sound to a film trailer, and in turn, was given a job in special effects at MGM. “I had enough background in industrial plants and mechanicals so that I thought the competition wouldn’t be too tough,” Lambert quotes Shearer.

By 1928, Shearer was the head of MGM’s sound department — a position he held for 40 years. “Overnight, I was the one-man sound department,” Lambert quotes Shearer. MGM was the last major studio to make the conversion to sound, and they relied heavily on Shearer. He visited Bell Laboratories in New Jersey to study the latest equipment and hired a team.

With “more stars than there are in heaven,” MGM’s look was important, but so was its sound. “Douglas gave it a clarity and spaciousness unequalled at the time,” Lambert wrote. But Shearer didn’t just learn how to produce sound in the early days, he had to eliminate extraneous sounds. The cameras of the late-1920s were loud, so his team developed a quieter camera. He also faced issues of microphone placement, which was solved by creating a moving microphone on the boom to move with the actors, according to film historian Charles Foster.

Shearer created other innovations that became industry standards and landmarks, such as:

- The first lion’s roar that was heard behind the MGM logo.

- Shearer suggested synchronized singing with already recorded music for THE BROADWAY MELODY (’29), which became standard procedure with the playback system.

- He electronically created Tarzan’s famous yell.

- Shearer was able to “retouch” singing. For example, he would adjust the soundtrack frame by frame if a singer like Jeanette MacDonald went flat in the high-note range.

With a total of 14 Academy Awards, Shearer was awarded seven competitive awards from 1930 to 1958, ranging from Best Sound, Recording to Best Special Effect and seven others for technical and scientific achievements. He received the award for Best Sound the first year it was introduced for the film THE BIG HOUSE (’30).

Always innovative, Shearer’s projects took him outside of sound as well. He developed an improved system of color process photography. He also worked on the 65mm big screen look for BEN-HUR (’59).

During World War II, he took a hiatus from films to help the government. Shearer helped with the research and development of radar and devices that determine when and where nuclear explosions take place, according to his New York Times 1971 obituary. When President Roosevelt offered Shearer a civilian award for his work, this was one accolade he declined. “I didn’t do it for the personal glory,” Shearer told Roosevelt. “I did it to help save lives and get the war over and done with.”

Though Shearer is considered by many one of the most influential figures of Hollywood history, it’s those in front of the camera, like his sister Norma, that are better remembered today. In a 1963 interview, actor Spencer Tracy noted that Shearer was the only person he knew to have a plethora of Academy Awards and to never be seen on screen. “He has made many stars by his achievements … I wonder where I would have been today if it wasn’t for the genius of this man,” Tracy said. “He is a star himself, but he will never admit it.”

Album Cover Art: Oboist Edition

Classical recording artists face a daunting task selecting just the right image to put on the cover of their recordings, especially when attempting to incorporate an instrument into the picture.

We recently received a donation of recordings, most of which feature the oboe, so here’s a quick look at oboists and their varied approaches to album cover art.

Look away!

Oboenkonzerte / Pierre W. Feit

When it’s too difficult to make eye contact with the oboe, simply look in the opposite direction.

This is a great cover that makes good use of bright colors against the tuxedo to say, “I’m playing Hummel and it going to be formal, but fun!”

Bring a friend/accompanist

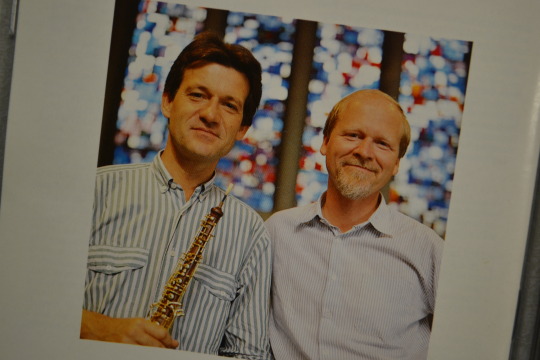

Oboe Sonatas / Hansjörg Schellenberger

To avoid the awkwardness that can come from trying to pose alone with one’s oboe, bring another person into the picture to balance the composition.

Under the chin

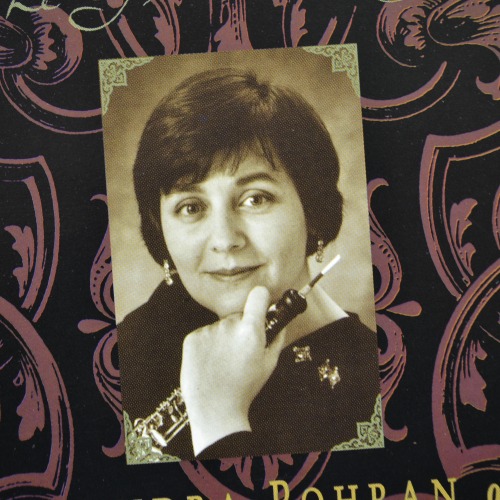

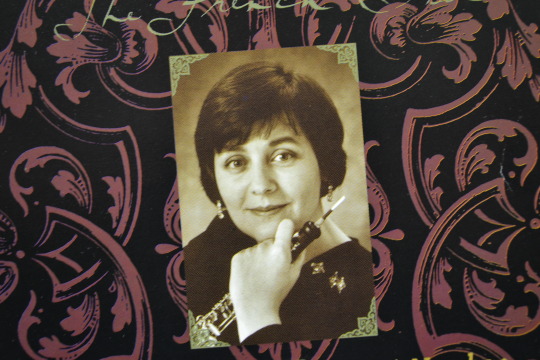

The French Oboe / Alexandra Pohran

Flashes back to your high school yearbook…well, at least mine, if you swap the oboe for a flute.

To the side

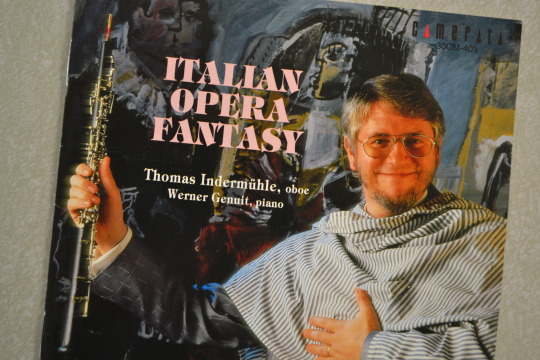

Italian Opera Fantasy / Thomas Indermühle

If the oboe is crowding it’s way into the camera shot, then add some space between you and it.

On the knee

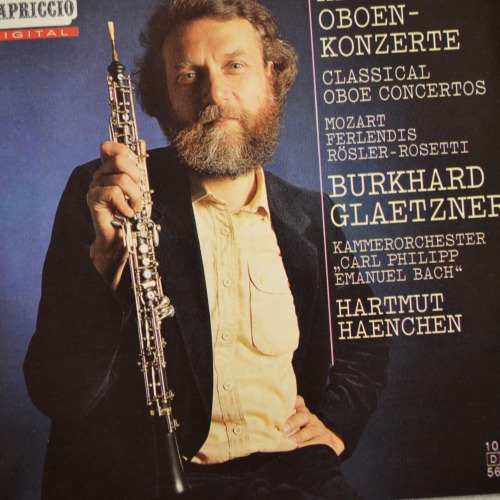

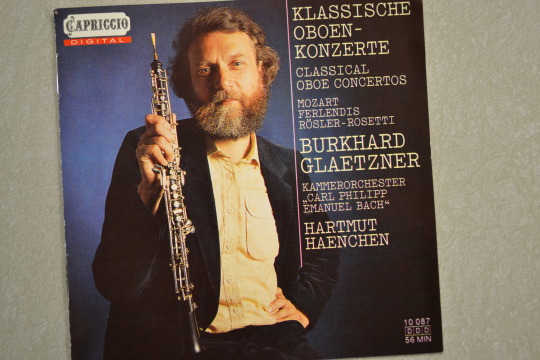

Klassische Oboenkonzerte / Burkhard Glaetzner

This is pretty classic stance for instruments with bells. Hold the oboe perched on the knee like you’re counting a long rest during a symphony rehearsal and you took this photo to fill the time.

————————————————————————————–

Is there an instrument you’d like to see featured in this series? Let us know!

Post link

Today’s #TechTuesday brings us a Pallo-Photo-Phone, a device developed by Charles A. Hoxie (1867–1941) of the General Electric Company for the purpose of “photographing” and reproducing the human voice.

The text accompanying this photograph, captured on November 6, 1922 declared that the Pallo-Photo-Phone would become “the apparatus which will make talking movies a successful reality and has introduced into radio broadcasting an entirely new element - the possibility of making a master record from which copies may be made and reproduced in the four corners of the world, just as the phonograph record is made.”

This photograph is part of Hagley Library’s collection of Chamber of Commerce of the United States photographs and audiovisual materials, Series II. Nation’s Business photographs (Accession 1993.230.II). The Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America formed in 1912 with the purpose of advising the government on issues facing industry and business throughout the country. The majority of images in this digital collection are photographs that were taken for the Chamber’s publication, Nation’s Business.

Published from 1912 to 1999, the monthly magazine proved invaluable in communicating the Chamber’s messages to business and government, and the magazine featured images by many of the country’s most prominent photographers. This collection has not been digitized in its entirety, but you can view a selection of images from it online now in our Digital Archive by clicking here.

Post link