#special collections

This post was written by Nicole Arnold, Summer 2021 Classics Department Intern.

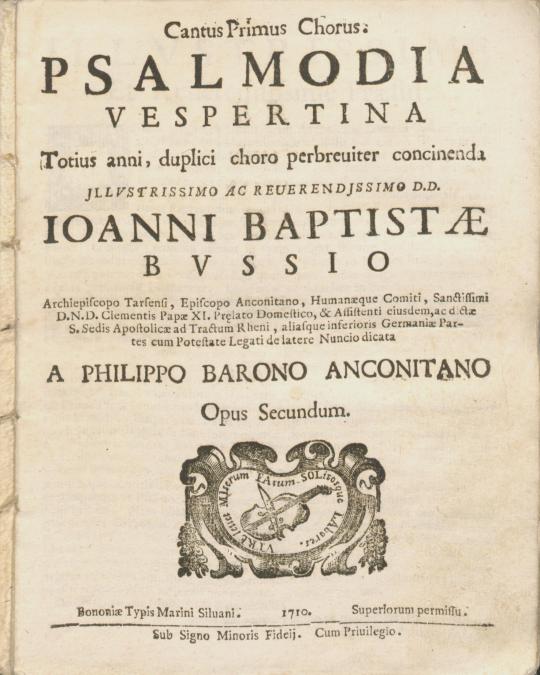

(Above: Title page, Psalmodia vespertina by Filippo Baroni, c. 1710, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System)

Like in any language, certain Latin words have different meanings in different contexts. Latin written in a religious context particularly changes the meanings of words. The Psalmodia vespertina, circa 1710, in the Archives & Special Collections contains a psalm that furthers this point.

The word “Domine,” which in Psalm 19 refers to God, is a form of the Latin noun “dominus.” In its purest form, “dominus” means “master.” However, in the religious context, it means “the Lord.” Using the word that means “master” is to indicate God’s almighty power. Furthermore, since “Domine” is in the vocative case, God is being addressed directly. It is best translated as “oh Lord.”

Other, more mundane words also take on different meanings with certain devices. For instance, the word “insaecula” technically does not exist in Latin. “Saecula” by itself has several meanings, such as “age” or “generation.” Adding the prefix “in-” changes the meaning, though; adding it makes the word “insaecula” mean “forever.”

Capitalization, much like in English, also gives words new weight in Latin. On its own, “patri” means “father.” However, when it is capitalized, “Father” takes on a religious meaning and refers to God. The same construction happens with “Filio,” meaning “son” or “son of God.” The word “sancto” is in a class of its own since the definition is literally “holy,” and modifies “Spiritui” to mean “the Holy Spirit.”

This post was written by Nicole Arnold, Summer 2021 Classics Department Intern.

(Above: A modern approximation of a decacordum. Image from Liuteria Severini.)

One of the most constant aspects of music across time has been instruments. Even if their names are different than what they once were, the sound and function of the instrument is often the same. The instruments of ancient and medieval times very much inform the modern music world. Similar instruments often exist across multiple cultures and religions too. Churches in the Middle Ages included certain instruments in their music that had connections to ancient Greece and Rome, especially string instruments. Some of these included the decacordum and cithara.

The decacordum is defined as a ten-stringed instrument (perseus.tufts.edu). The prefix “deca” means “ten”; the “cordum” suffix refers to the strings. The word itself seems to have been a general term for ten-stringed instruments. Some scholars believe that ten-stringed instruments in the church referenced the ten commandments while the sides of them represented the four gospels. (Kolyada 31) Other sources, like the Musurgia Universalis (circa 1650) of University of Pittsburgh Library Systems’ Archives & Special Collections, describe the instrument’s strings as similar to a spiderweb. This is most likely in reference to their intricate weaving. Modern depictions of the instrument resemble a small harp. It is possible that could be what the spiderweb comment means; the trapezoid in a spiderweb looks much like the harp. The decacordum was one of several string instruments commonly used in the church.

(Above: Apollo, the Greek god of music, playing a cithara. Image from wikipedia.org.)

Another instrument of the medieval European church was the cithara. Although it was used like a harp in the church, the cithara originated in ancient Greece as a type of lyre, which resembled a guitar. The ancient Romans adopted it into their culture as well, and it became the most common instrument in Rome. It had anywhere between three and twelve strings. It is believed that “cithara” is the etymological stem of “guitar” (britannica.com). Descriptions of its features in medieval church music imply a resemblance between the two instruments. The “choking strap” of the cithara is mentioned in the psalm “Confitebor Angelorum,” in the Archives & Special Collections’ Psalmodia vespertina. (circa 1710) Since this instrument was a kind of lyre and had a strap that went around the neck, it can be inferred that the modern twelve-string guitar bears a resemblance to it. Notably, 21st-century musician Taylor Swift plays a twelve-string guitar rather than a typical six-string one; the doubled number of strings creates a more intricate sound.

(Above: Taylor Swift performing “Sparks Fly” on a twelve-string guitar. YouTube video.)

Works Cited

Kolyada, Y. (2014). A compendium of musical instruments and instrumental terminology in the bible. ProQuest Ebook Central <aonclick=window.open(‘http://ebookcentral.proquest.com’,’_blank’) href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com’ target=’_blank’ style='cursor: pointer;’>http://ebookcentral.Created from pitt-ebooks on 2021-06-14 20:13:12.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Kithara”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Nov. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/art/kithara. Accessed 29 June 2021.

“Psalterium Decachordum.” Liuteria Severini, https://liuteriaseverini.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=90&Itemid=1030. Accessed 29 June 2021.

“Cithara.” Wikipedia,17 April 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cithara#/media/File:Apollo_Musagetes_Pio-Clementino_Inv310.jpg. Accessed 29 June 2021.

“Decachordum.” Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=decachordum. Accessed 29 June 2021.

Kircher, Athanasius, and Jacobus Viva. Musurgia universalis; sive, Ars magna consoni et dissoni in X. libros digesta … Romae: Ex typographia haeredum Francisci Corbelletti, 1650.

Baroni, Filippo. “Psalmodia vespertina: totius anni, duplici choro perbreuiter concinenda : opus secundum” Bononiæ: Typis Marini Siluani, 1710.

Swift, Taylor. “’Sparks Fly’ (acoustic) Live on the RED Tour!,” YouTube Video, 0:48, March 15, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nx-5bHeC6xo

Professor Rachel Grozanick’s ENGLIT 0512 Narrative and Technology class visited Archives & Special Collections during the Spring 2020 term. Students had the opportunity to closely examine collections around the themes of constructing the canon, inclusivity, alternative formats, and fandom. Students examined artists’ books, comics, pop-up books, Modern Language Association editions, and Clifton Fadiman.

Today it is easier than ever to find and participate in communities centered around any niche media series or hobby imaginable, but that was not always the case. Before the age of the Internet, it was much harder for the earliest fans to connect and correspond with each other. One of the earliest ways these gaps were bridged was through the creation and limited publication of fan made magazines, often abbreviated to fanzines or simply zines. Small audiences developed around these independent projects, and over time the focuses of many of these once tiny and relatively unknown groups have grown to be parts of the mainstream consciousness. This growth is largely due to the widespread and increasingly accessible virtual communication platforms and social media. Despite the differences in format, platform, etc, there are striking similarities between old fan interactions in fanzines and modern fan interactions online.

The lightning fast response times of internet forums today may be taken for granted now, but decades ago discussions around media and fandom depended on the postal systems to flourish. This is often lamented in The Invisible Fan #7, an issue of a zine containing a debate relating to feminism, inclusion, and the effectiveness of feminist groups comprised entirely of men, as the editor, Avedon Carol, occasionally mentions her annoyance with having to maintain and truncate an active mailing list along with the slow response time of those writing to respond to her (Carol 13, 21). These responses took the form of a “loc”, or letter of comment, which subscribers would write in to the publishers or creators to give their thoughts on the topics discussed or the quality of the zines themselves (Southard 27). This particular issue of The Invisible Fan also contained a number of these referring to previous issues, which revolved around similar topics, specifically women and writing science fiction (Carol 18-19). This entire issue is almost like looking at a transcription of an internet forum discussion, especially in the case of the locs, as many of these have a bit of a dialogue between the fans and Carol.

Figure 1: An excerpt from one of the many locs from The Invisible Fan #7 (Carol 18).

While originally these dialogues consisted only of fans themselves, overtime industry professionals and creators began to get involved directly as well. This is not solely due to the rise in social media and instead has roots in zines themselves. In his book detailing the history of zines, New York University Gallatin Professor of Media and Culture Stephen Duncombe notes that science fiction zines were integral in pushing for more interactivity between fans and media producers, as well as between fans and other fans (Duncombe 114). Originally, fans simply wrote in letters with concerns or requests to the relevant publishers as well as to each other, and it was this active participation, Duncombe argues, that eventually allowed fans to play a part in shaping the final products as opposed to just consuming them (Duncombe 114). A more fully realized version of this relationship can be seen today with fans reaching out to companies and individual creators on social media platforms, where they can discuss their favorite franchises with the people responsible for them. Because some of these platforms have millions of users, in the past there have been instances where enough of them have formed collective pushes towards these companies to elicit changes they deem necessary. A recent example would be the delay of the movie Sonic the Hedgehog, as after initial trailers were uploaded fans were so outspoken in their dislike of the main character’s design that the movie’s release date was pushed back in order to update it. Clearly modern fandoms have a much larger impact than a handful of letters.

That isn’t to say that fans and zines never had any interactions with those working in the industries before the Internet. Another zine, Incognito, which was centered around Marvel and DC comics, published an issue that contains an interview between one of its editors, Rick Jones, and the late Marvel Comics Writer Stan Lee, who is responsible for many of the superheroes in mainstream culture today (Jones et al. 4). It’s more common now because it’s much easier to reach out to the people behind shows and movies directly. Creators and companies themselves have also taken steps to involve fans by hosting promotional question and answer sessions on Twitter or Reddit before upcoming releases, among other things. This, along with the added level of anonymity online usernames provide that may make others more comfortable in participating, ensures that discussions are open and available to everyone.

Some other avenues of fan discussion and discourse include the sharing of related pictures and fan made art. Because resources were often limited while making these zines, some took it upon themselves to recreate officially produced artwork via copying or tracing the official art as best they could, like in figure 2. Alternatively, some took to creating their own original artwork instead of or in addition to tracing. In the current year, we still often circulate and share images or memes of our favorite shows, and it’s never been easier to find high resolution reference material, images or otherwise, via Google or similar search engines.

Figure 2: Doctor Strange characters traced by Bill Schelly in order to provide simple visual aids (Jones et al. 9).

What may be lost today, however, is the amateurish charm of yesteryear due to the advances and availability of better tools and technology. Both The Invisible FanandIncognito contain some sort of spelling errors or printing errors, which can be seen in figure 3. While this may hurt any professionalism they may have aspired for, it could also be argued these mistakes add to the charm, as these projects were usually the work of small but dedicated teams or even single individuals. They might not be incredibly polished, but the passion shines through regardless. Currently, with the prominence of word processors with automated spell checking software, unintentional spelling mistakes are almost always seen negatively due to how easy they are to fix. This luxury was not a feature of the typewriters the original zines were written on. There is also a seemingly endless supply of such high quality fan art now due to the increasing availability of professional software. That doesn’t mean that the artists and fans of today don’t have the same levels of dedication as those in the past. In fact, as these fan made pieces grew in elaboration, the time and technical skill required to produce them grew as well. Regardless, these works are still shared far and wide with others, but through the Internet instead of the mail or in person.

Figure 3: A particularly gruesome printing error. A spelling mistake is also visible in the top right corner (Carol 5).

The fans of today are still largely doing what the original fans accomplished through their zines decades ago except now there’s a much wider audience. The large communities of today are so expansive that the feeling of being a part of a small, tight-knit group might be lost. For example, it would be impossible to know every single individual personally today, due to some communities being so expansive they encapsulate millions worldwide. What may have felt like a special and even exclusive club back then now has the door bolted open for anyone and everyone to participate in. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and in fact on the whole it’s more beneficial for those who want to get involved and participate. It’s now possible for everyone to be an active participant, fan content producer, or just an observer, in the current cultural climate. The activities are largely the same, it’s simply the avenues of distribution and communication that have changed.

- Derek Halbedl, undergraduate, University of Pittsburgh

Works Cited

Carol, Avedon. “The Invisible Fan.” The Invisible Fan, 1978, pp. 1–21.

Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from underground: Zines and the politics of alternative culture. Microcosm Publishing, 2014, pp. 114

Jones, Rick, and Billy Schelly. “Incognito.” Incognito, Sept. 1965, pp. 1–17.

Southard, Bruce. “The Language of Science-Fiction Fan Magazines.” American Speech, vol. 57, no. 1, 1982, pp. 19–31. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/455177. Accessed 2 Feb. 2020.

As the sun continues to shine down on London outside, we’re inside digitising a volume printed in 1570 full of woodcut illustrations alongside well-known fables. The section of Aesop’s fables have woken up memories of childhood storybooks, like this one illustrating the tale of The North Wind and the Sun.

Post link

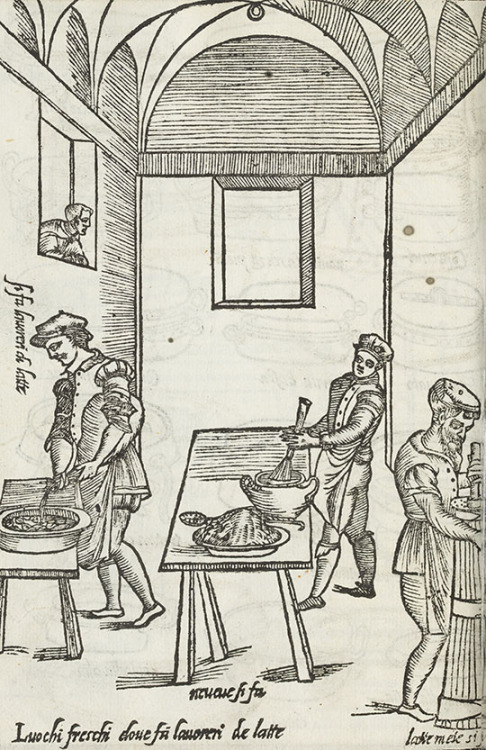

We recently digitised some illustrations from a cook book written around 1570 by Bartolomeo Scappi, He was head chef for several cardinals and to Pope Pius IV and V.

It is divided in six books, in each book he gives recipes and food selections according to the seasons of the year. The illustrations in the book show the types of utensils and pots, some of which were shown for the first time in the this book. This book is also the first to show an image of a fork!

Our volunteer Gina translated two recipes from the book for you to enjoy and try out in your kitchens over the weekend! Let us know if you experiment with these early modern recipes:

Fiadoncelli (pastry dough in tubular shape with various fillings)

Take very fine flour and mix it with white wine, rose water, sugar, salt, oil and saffron, making sure the quantity of rosewater is more than that of wine and everything is lukewarm. Mix the dough, making sure it is not too hard. Make a thin long pastry.

For the filling, take pine nuts which have been soaked in water and dates simmered in wine and finely chopped, currants simmered in wine and finely chopped raisins without seeds. Mix all with sugar, mints leaves and crushed marjoram.

Shape the fiadoncelli with the thin pastry and add the filling. Fry with high quality oil. Serve warm and dust with sugar.

Dough for various doughnuts

Take one pound of almonds, grind it in a mortar and mix with three pounds of lukewarm water. Heat up. Take two ounces of yeast mixed in warm water, add this to almond milk, add a little salt, four ounces of sugar, eight ounces of white wine, 4 ounces of oil, two pounds of fine flour and a little saffron to add colour.

Whip the dough with a wooden spoon for half an hour. Leave it to rest in a warm place for three hours. After whipping it again with a wooden spoon, cover the bowl for half an hour keeping in warm temperature, and then whip it one more time. Test the dough in hot oil. If it swells it will be perfect, alternatively, remix and leave it to rest. With the spoon make small or big doughnuts as one likes them, when ready serve warm with sugar dust.

If you want to try making doughnuts with additional ingredients, just make the dough more runny than add any of the following suggestions:

-any finely chopped fresh herbs

-cooked parsnips

-sardines

-salted anchovy

-apples

-thinly sliced courgettes

-boiled leeks

-prawns

-rosemary and sage

Post link

Did you know that The University of Idaho’s Administration Building as it stands today is actually a replacement of the original? Here’s a bit of the story, taken from our UI Campus Photography Collection:

“In the very early morning of March 30, 1906, the Administration building at the University of Idaho was fully engulfed in flames. Through the combined efforts of administration, faculty, staff, and students, some small pieces of the University of Idaho’s beginnings were saved. Dean Jay Glover Eldridge climbed a ladder into his office and threw entire drawers of documents to Judge Roland Hodgins (pioneer and proprietor of Hodgins’ Drug Store) who then gathered them from where they fluttered. Students managed to save the "Silver and Gold Book” (a jeweled box gifted to the University from the women of Moscow) and a stuffed mountain goat.

The university library was housed in the Old Admin and the majority of the books Miss Belle Sweet, the University Librarian, had managed to organize were lost. President James A. MacLean, a volunteer with the West Side Hose Company No. 4, could do nothing but watch as the heart of the UI campus was lost. As light came the next day, the once attractive edifice of education was nothing more than blackened skeletal walls and wet rubble. A feeling of mourning descended on the UI campus. Although arson was suspected nothing was ever proven.“

Learn more about our beautiful campus’ history via our UI Campus Photography Collection!