#special collections

Space Spiders, Lunatics, and Airships : Moon Voyage stories in Wilson Library

It’s a full moon tonight, so we thought that it would be a great time to feature our favorite moon voyage story in Wilson Library Special Collections–the only problem is, we couldn’t decide between these three amazing narratives! So we need your help, Tumblr followers! Read below, and help us decide which contender is the ultimate sci-fi adventure!

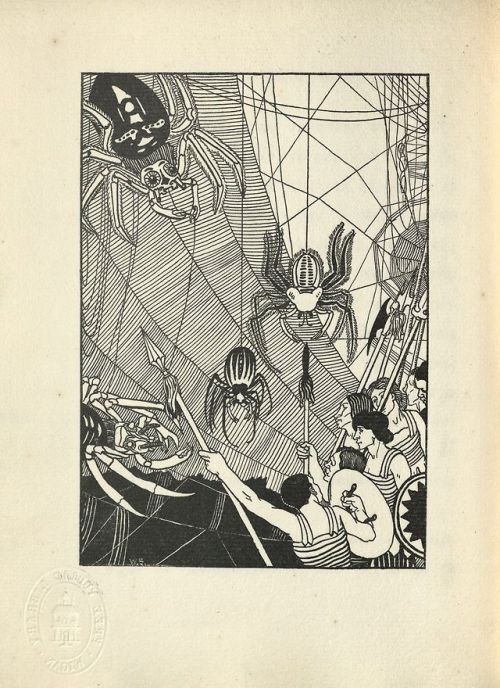

Contender 1: One of the earliest recorded moon voyage stories, Lucian’s “True History”was written in the second century AD in ancient Greece. This “true” history is filled with fantastic travel narratives, including the moon-voyage adventure in which a crew accidentally lands on the moon after their ship gets carried into the sky by an enormous gust of wind. The men then take part in a fantastic space battle between the alien armies of the sun and moon. (Bonus points: the space battle features giant spiders who spin web-bridges to lead their army across the sky).

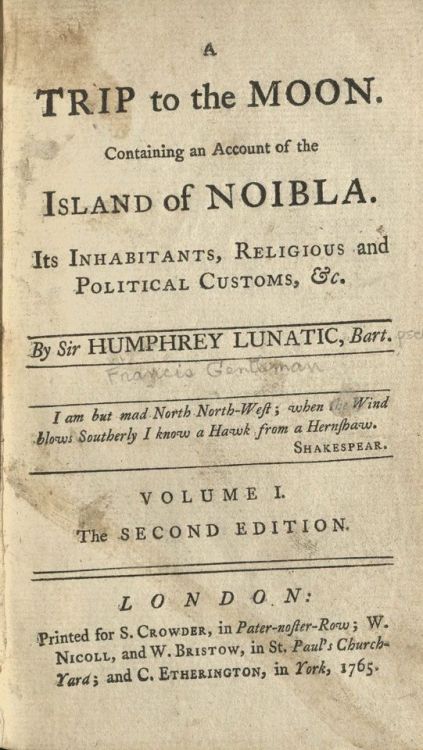

Contender 2:A Trip to the Moon (1765) was written by sir Francis Gentleman under the very appropriate pseudonym, Humphrey Lunatic. In this story, Humphrey falls asleep in a beautiful grove and (much to his surprise) wakes up in the Lunar world. How does he get transported, you might ask? The pamphlets in Humphrey’s pockets (which were, apparently, originally conceived in the Lunar kingdom) attract a tractor-beam that pulls Humphrey up towards the moon. Full of tongue-in-cheek humor, this story is memorable both for its whimsy, and for its cutting social commentary. (Bonus points to Francis Gentleman for both his amazing pen name, and also for including an elaborate family lineage for the “Lunatic” family that includes an ancestor named Whimsical Lunatic, Esq.).

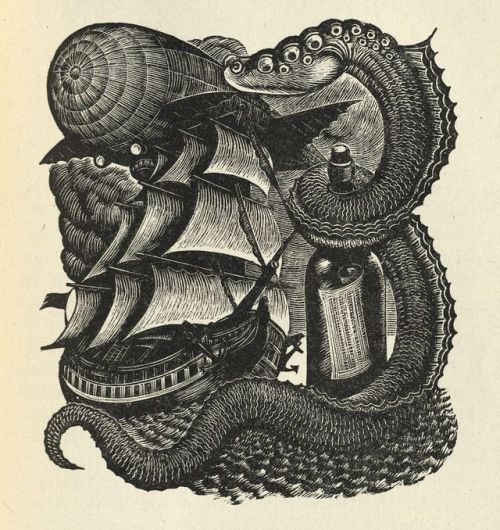

Contender 3: Last but not least, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfall” (1835) features a slightly more technologically advanced means of conveyance. In this story, the protagonist takes an airship to the moon. Not only is this story an interesting moon-voyage account in its own right, but in addition, it was in fact, originally created as a hoax. Shockingly, Poe’s tale was not the only moon hoax of 1835, but was second in renown to the “great moon hoax” of the same year. In this moon hoax, the New York Sun (a tabloid newspaper) published a series of articles on fake “celestial discoveries”–which included the discovery of a species of intelligent lunar bipedal beavers. (Bonus points to Poe for not only creating his moon-travel hoax, but also for dreaming up his 1844 balloon hoax–in which he convinced readers of the New York Sun that a man had crossed the Atlantic in just 3 days in a new form of airship).

Got opinions on which of these three is the best moon voyage story? Comment below to let us know your pick!

Post link

5 Things Thursday: DAM, UX, Snow in Vegas, Graph Databases for Humanities

Happy new year! Here are five things:

- Insights on DAM customer service from none other than John Horodyski.

- Are you moving assets in to a digital asset management system? Check out this great advice from Laurel Norris.

- UX trends for 2016 predicts that content strategy is the new information architecture.

- Interesting interview with Suellen Stringer-Hye, the Linked Data and Semantic Web Coordinator…

Industrial wasteland turned cultural gem, let’s geek out today looking at before, during, and after photos of building Millennium Park.

Before:

A railway, parking lots, and sparse greens in the space where Millennium Park is now (looking east).

After:

Looking west and slightly south, Millennium Park in all its glory.

Grab yourself a slice of birthday cake and look through more photos in our digital archives: shar.es/NkP4S

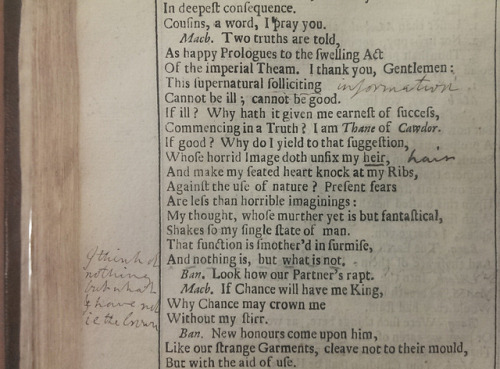

Today, April 23, is Shakespeare’s birthday! Maybe. Supposedly. It was certainly the date of his death in 1616, but it also commonly celebrated as the date of his birth, some 52 years earlier in 1564.

Several editions of the Bard’s works were printed before his death, but the most complete and most famous collections of his plays are the large folio editions, produced posthumously.

While these beautiful and rare 17th century Shakespeare folios are a significant improvement over the earlier “bad” quarto versions, they are far from perfect copies of Shakespeare’s works.

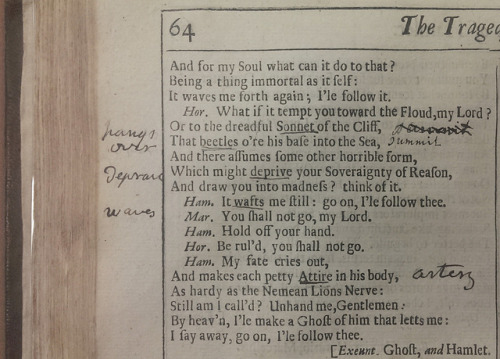

In the case of own Fourth Folio, it appears as though a previous owner sought to correct some of the numerous typographical errors throughout the volume. Our dutiful annotator has also added several marginal notes commenting on various passages in the text.

Some of these typos really change the meaning of the text in humorous ways:

If good? Why do I yield to that suggestion,

Whose horrid image doth unfix my heir [hair]

- Macbeth, Act I, Scene 3

What if it tempt you toward the Floud, my Lord?

Or to the dreadful Sonnet of the Cliff [summit]

- Hamlet, Act I, Scene 4

My fault is past. But oh, what form of Prayer

Can serve my turn? Forgive me my foul Mother [murther/murder]

- Hamlet, Act III, Scene 3

All those bored scholars with nothing better to do than overanalyze Shakespeare’s works looking for hidden messages should have a field day with some of these passages.

Post link

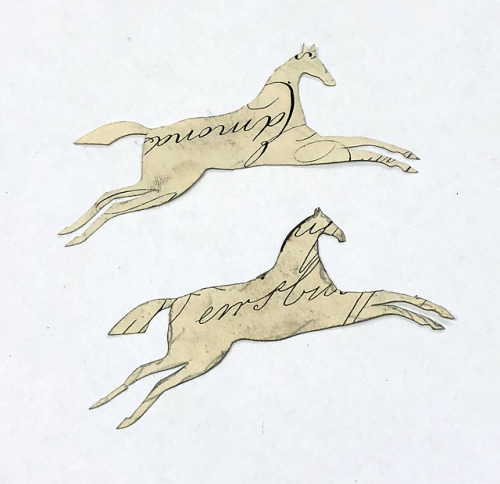

Reveries of a Bachelor

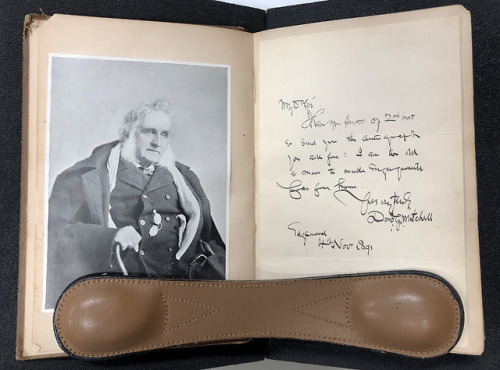

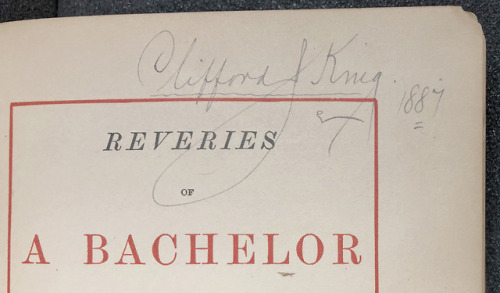

Though very few modern readers would recognize the name of Donald Grant Mitchell, his collection of sentimental vignettes, Reveries of a Bachelor (written under the pseudonym “Ik Marvel”) was one of the most popular novels of the Victorian era. It was a favorite of Emily Dickinson, and has even been compared to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in its popularity and influence.

Aside from serving as U.S. consul to Venice from 1853 to 1854, Mitchell (1822-1908) spent much of his career writing at Edgewood, his estate near New Haven, Connecticut. Portions of Reveries of a Bachelor first appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1849, and then in 1850 it was published in book form, going through dozens of editions in the following decades. Excerpts were even reprinted by insurance companies and the makers of tonic medicines to be distributed to potential customers.

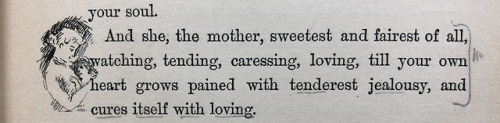

The text itself is divided into four “reveries” in which a bachelor contemplates boyhood, marriage, country life, travel, and even the phenomenon of dreaming itself. Chapters include “Smoke – signifying doubt,” “Blaze – signifying cheer,” and “Ashes – signifying desolation.”

We were fortunate enough to have recently acquired a fascinating copy of the 1886 New York edition of Reveries of a Bachelor. Our copy was originally purchased in 1887 by Clifford Julius King (1865-1910), an Ohio attorney who practiced in Ashtabula (as King did not marry until 1891, he was still a bachelor himself when he bought the book). King had more than just a passing interest in books, as he was a member of the Rowfant Club, an organization for bibliophiles founded in 1892 in Cleveland and still active today.

King is presumably responsible for several other characteristics that make this copy stand out. First is a signed letter by Mitchell, perhaps written to King, pasted into the volume along with two portraits of the author. The letter reads:

My dr. Sir –

I have yr favor of 2nd inst

to send you the autograph

you ask for: I am too old

a man to make engagements

far from home.Yrs vry truly,

Dond. G. MitchellEdgewood 4th Novr. 1891

Additionally, an artist known only by the initials B.K.C. has contributed numerous pen and ink wash illustrations to this copy, some of which bear an 1887 date. In total, there are seven full-page images, 17 head and tail vignettes, and 73 marginal illustrations. These drawings really bring Mitchell’s text alive, and the marginal vignettes especially heighten the dream-like aspect of the book, depicting subjects such as a hand lighting a lamp, a foot entering a shoe, or the floating head of a woman.

Though it is not explicitly stated, it is likely that Clifford Julius King, due to his bibliophilic interests, was responsible for embellishing this copy by collecting the Mitchell paraphernalia and assembling it together with the illustrated text. The result is a copy of Reveries of a Bachelor that is truly unique — and truly special!

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b12953883~S39a

Post link

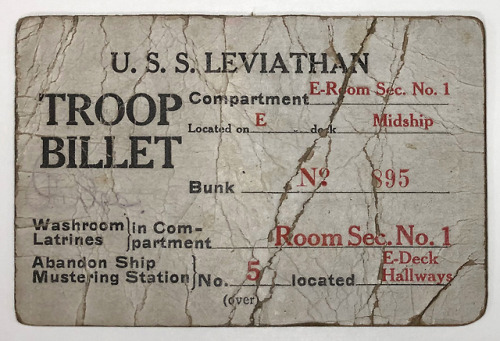

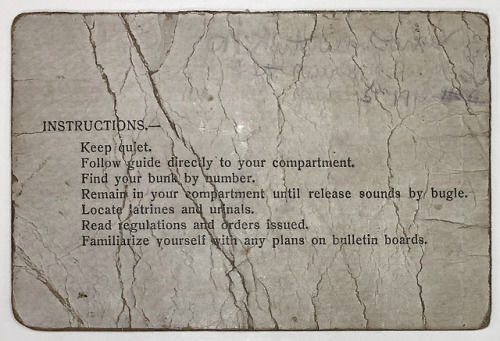

More highlights from our file of “Things Found in Library Books!”

One interesting piece from this collection of orphaned ephemera is a troop billet card for the U.S.S. Leviathan, a massive German-built steamship seized by the United States in 1917 and used as a troop transport during World War I. While we can’t quite make out the name penciled on the back of the card, we can (just barely) read the annotation below, which allows us to date this particular voyage:

Left New York Harbor

June 15th 1918

Can anyone read the name of the soldier in bunk #895? While we can’t say for sure if the former owner of this card made it home from the War, the fact that the card survived gives us some hope.

During its tenure as a military transport, the Leviathan ferried over 119,000 American troops between the United States and Europe. After the War ended, the ship was refitted again to serve as a passenger liner for the United States Lines, and continued to sail across the Atlantic for another 20 years.

Post link

There’s a lot more to studying provenance than deciphering arcane inscriptions and other marks of ownership. Sometimes previous owners will leave other traces of themselves behind, like these loose items we’ve found stuck between the pages of many of our old books.

These pieces of ephemera, or transitory materials originally meant to be discarded after a few uses, have survived against all odds — in some cases for over 100 years — as forgotten bookmarks, safely tucked away and waiting for our librarians or catalogers to stumble across them.

Unfortunately, these particular ephemera are orphaned materials, their original sources unknown or undocumented. Where they might have come from, what books they were originally found in — these remain mysteries that we will probably never solve. But while their usefulness as pieces of provenance evidence is likely nonexistent, these fragile, rarely-preserved fragments of another time and place are still interesting in their own right.

Post link

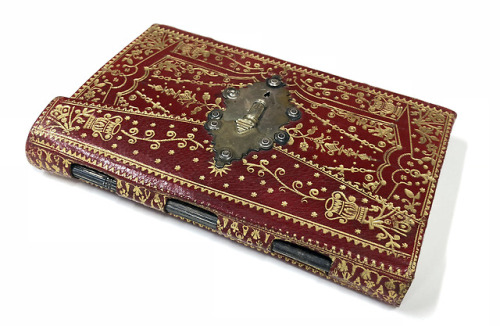

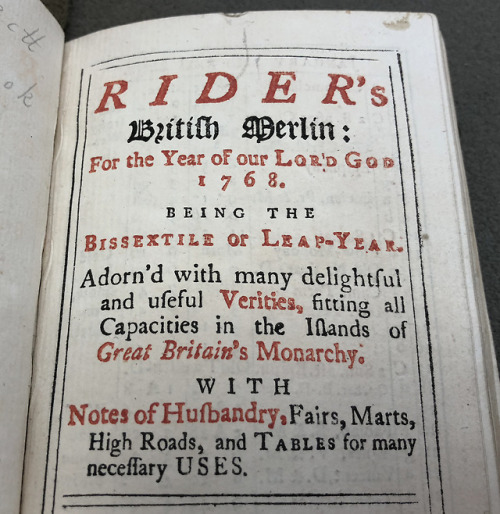

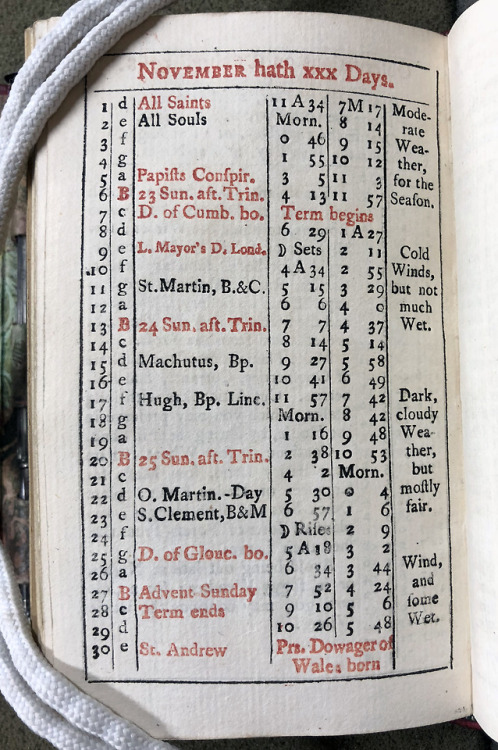

Unlocking a 250-Year-Old Almanac

Special Collections has recently acquired an intriguing copy of Rider’s British Merlin, an almanac published in London in 1768 — 250 years ago this year!

Rider’s almanac first appeared in 1656, “compiled for the benefit of his country” by one “Schardanus Rider,” believed to be an anagram of the name of physician and astrologer Richard Saunders (1613-1675). The almanac continued to be published for many years after his death.

A number of special features make our copy uniquely interesting, such as its elaborate red morocco binding. Perhaps most fascinating is the metal lock, which is actually even more complex than it might appear at first glance. In spite of the provided key, it seems that the only way to truly open the lock is through a secret mechanism — by gently sliding one of the rivets connecting the lock to the cover, the inner latch shifts, and the flap can be opened.

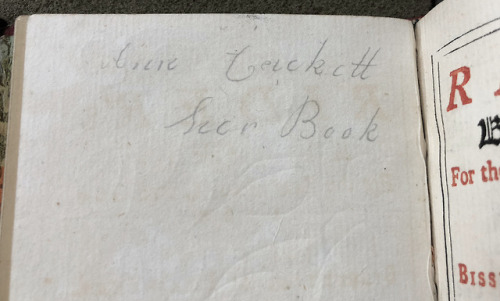

A convenient slot is incorporated into the flap to store a metal stylus, which is (happily) still present. This was used for taking notes on a pair of waxed sheets bound in at the front of the volume, which effectively acted as erasable writing tablets. In much the same way that the ancient Romans used wax-filled wooden frames for temporary note-taking, the pages in this almanac could be incised with the stylus and then erased at the appropriate time. An owner of this volume — perhaps Ann Cackett (?), who wrote her name on one of the flyleaves — has used the stylus many times, leaving incisions behind in the form of repeated circles and other rudimentary markings.

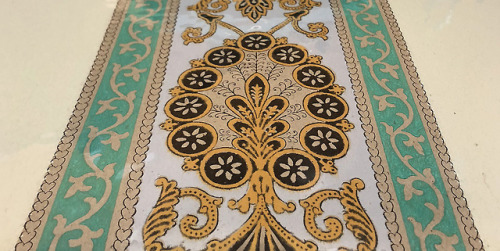

Inside each cover is a little fold-out pocket for the storage of important documents, though sadly they arrived at our library empty. These pockets are partially formed by the end-papers, which are made from beautiful multicolored Dutch gilt paper (actually originating in Germany). Our papers bear a portion of the name of their maker: “Johan Wilhelm.”

It’s easy to concentrate on this almanac’s bells and whistles, but it is also rewarding to look at its contents. It opens with a handsome calendar, printed in red and black, that incorporates religious, astronomical, meteorological, and agricultural observations. Other sections include a list of the year’s moveable feasts (holy days that occur on different days each year), a calendar of eclipses, a zodiac man (a diagram of the relationships of the planets to various parts of the human body), a table of the monarchs and the dates of their reigns, a description of the country’s major roads with the distances between towns, and an extensive list of the fairs regularly held in England and Wales.

Several pages are filled with the reckoning of the years since major events – 4061 since Noah’s Flood, 315 since “printing first used in England” (this is about 20 years earlier than the date generally accepted today), 188 since “a blazing star in May” was observed, and five since “a general peace.” Finally, there is a tipped-in sheet documenting “An account of the holydays” for 1768. (This is unrecorded in the English short title catalogue.)

We are excited to add this unique almanac to our collection, and look forward to welcoming you into our reading room to see it in person!

Post link

“It had the power of a thousand scorpions…”

- Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

Sometimes books can kill.

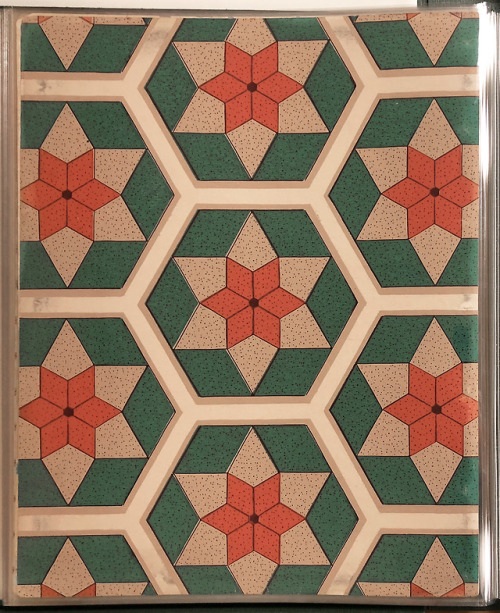

Take this book, for example. Shadows from the Walls of Death is a 19th century collection of arsenic-laced wallpaper samples. Each of the striking specimens was colored with an arsenic-based pigment, and touching the pages with your bare hands could make you seriously ill, or worse.

Hopefully by now you’ve read our 2015 Tumblr post onShadowsor Atlas Obscura’s recent article on the poison book, but here’s some background in case you haven’t:

Copper arsenite was not an uncommon ingredient in paints and pigments throughout the 19th century, most often used to produce the vibrant greens known as Paris Green or Scheele’s Green. While people of the time knew that arsenic was dangerous if ingested, they saw little risk in using the poisonous element to color wallpaper – after all, who’s going around licking their walls?

But then in the 1870s, Robert Kedzie – a doctor, MSU chemistry professor, and public health advocate – showed that fine particles of this arsenical wallpaper could shed when touched, or worse: they could “dust off” into the air, causing people to fall ill and die by just existing in a house coated with the stuff.

Kedzie put together 100 books of the deadly wallpaper samples and sent them to libraries throughout Michigan, to educate the public about the potential dangers of this common household item.

Only a handful of copies of this toxic book remain – most were destroyed long ago due to their poison pages. Of the surviving volumes, MSU’s copy is believed to be the most extensive, or most complete – containing over 130 individual wallpaper samples.

Most of the wallpaper specimens feature the color green, but not all – the same arsenical dye that went into the infamous Paris Green or Scheele’s Green was often mixed to form other colors, and many of our samples boast beautiful deep blues and golden yellows.

Most of the images here have never been seen before. Some day it’s possible that we will digitize our copy of Shadows, as the National Library of Medicine has done with theirs, but that poses some significant challenges.

In the meantime, every page in our copy has been painstakingly encapsulated in archival sleeves – meaning that patrons can safely view the book up close without fear of succumbing to arsenic poisoning. But if you can’t make it out to see the volume in person, I hope you will enjoy these new photos of this intriguingly beautiful book.

Beautiful, but deadly.

~Andrew

Post link

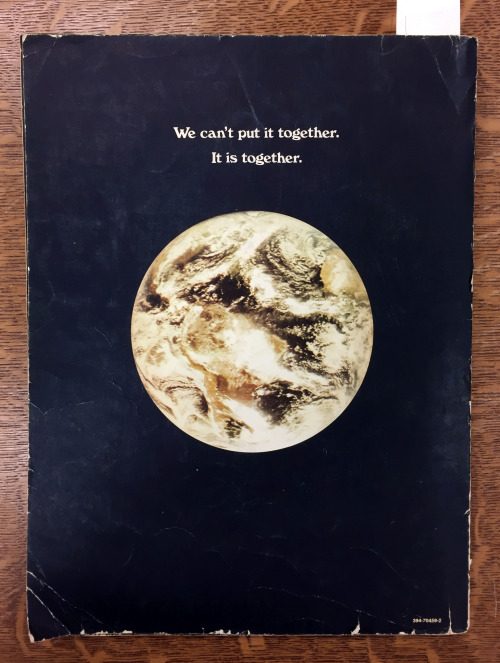

WE CAN’T PUT IT TOGETHER. IT IS TOGETHER.

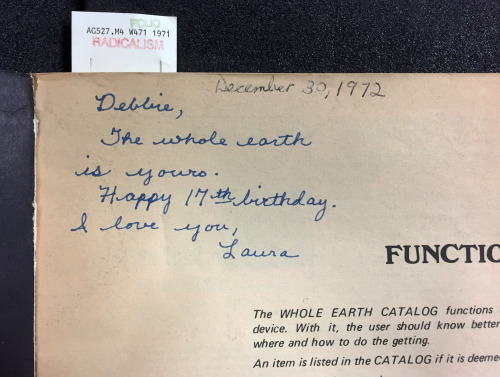

Last semester a Lyman Briggs College class (LBC is a residential college here at MSU that bridges the humanities and the sciences with interdisciplinary teaching and research) used The Last Whole Earth Catalogas one of its texts.

Students used an online version of the catalog, but were also encouraged to visit Special Collections where we have a number of issues and editions of that venerable icon of the sixties. I still recall the hours and hours I pored over the first Last Whole Earth Catalog I purchased in 1971. I was in VISTA at the time (Volunteers in Service to America) ready to change the world for the better and finding the Catalog as a guide to do just that. I was pretty successful with a neighborhood garden (the organic part would have to wait) among other endeavors, but the backyard yurt was a total flop. Seeing students almost a half century later looking through the catalogs in the reading room was deeply satisfying, especially when one student said that holding and seeing the print copy was so much better than the digital copy. Yes!

After one of the LBC students was finished, I spent some time revisiting the Catalog and found this lovely inscription from Laurie to Debbie dated December 30, 1972. Wherever these fellow travelers are today I hope they are well and would take as much satisfaction as I do knowing their Catalog is still being used and teaching, maybe even inspiring another generation.

~Peter

Post link

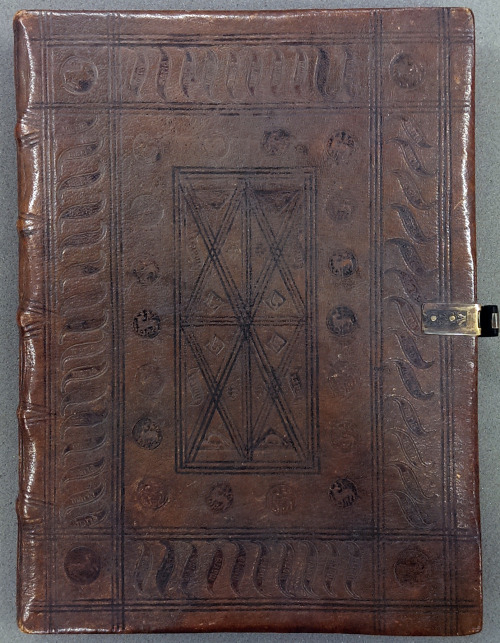

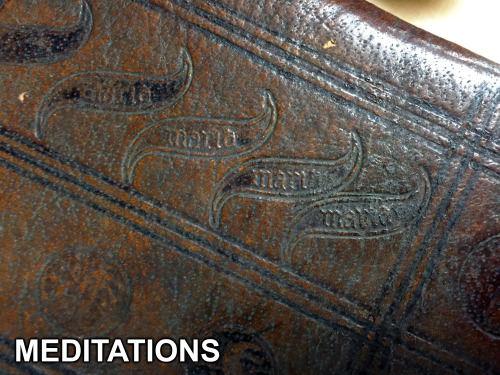

If you’re in the habit of reading descriptions of old books—and why wouldn’t you be?—you’ve likely come across something described as bound in period style or in a sympathetic binding. This typically means the book was rebound relatively recently, but rebound in a style consistent with the time period of the book’s original publication.

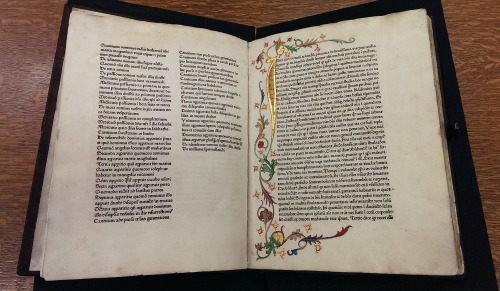

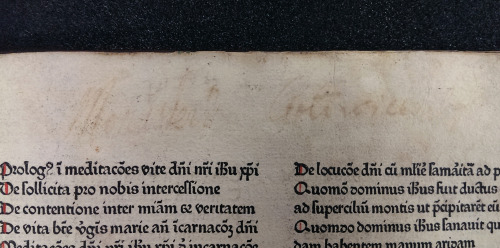

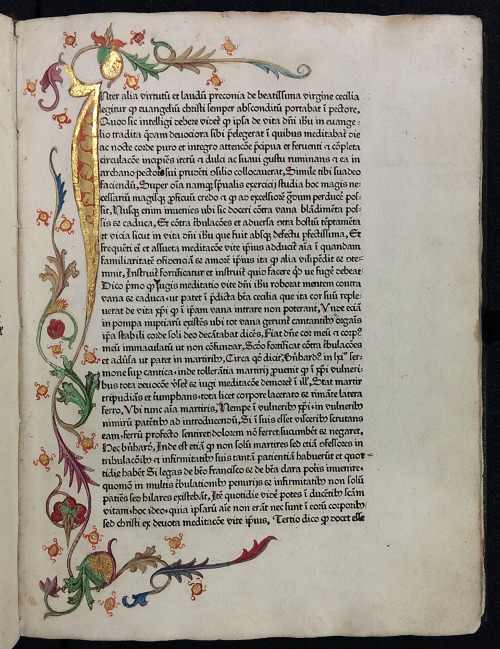

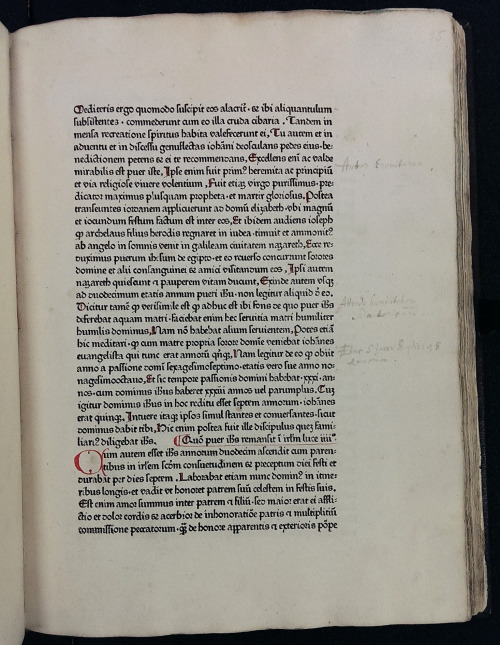

For example, our first edition of the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Life of Christ) was rebound in such a way. You can read more about this work—a recent acquistion—here.

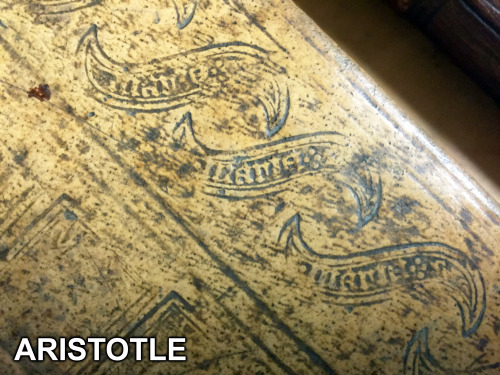

And shortly after the Meditations arrived, we received the first printed Greek edition of Aristotle (it was a very good summer), which underscored just how well done this period-style binding was. Although the books were likely bound about 400 years apart—the Aristotle around 1500 and the Meditations around 1900—the styles are strikingly similar. The combination of borders built up from different tools, surrounding a central diaper pattern, was a familiar style when both were published. The Aristotle binding is almost certainly German, so it’s no surprise that the binding of the Meditations, which was printed in Augsburg in 1468, emulates a 15th-century German style.

Of all the similarities, what most caught our eyes was a particular tool used to decorate the boards. While obviously similar, small differences distinguish them. The Aristotle version, for example, has four tiny dots following Maria, while the Meditations version has no dots; a double border surrounds the Aristotle tool—thick on the outside, thin on the inside—while the Meditations tool has a single border; the Aristotle tool measures over 3 cm from end to end, while the Meditations tool measures just under 3 cm. The sheer volume of such tiny differences among tools is staggering. The Einbanddatenbank, a database of 15th- and 16th-century finishing tools used on German bindings, records more than 600 versions of the Mariatool.

How do we know the Meditations binding isn’t original? There are a number of clues, the general as-new appearance being a big one, but subtler evidence is there. The spine edges of wooden boards were commonly beveled in the late 15th century, but they aren’t here. Spines were seldom decorated at this time, yet the binder of the Meditations couldn’t help but to add some restrained decoration. Could these features be found on bindings from the late 15th century? Sure. But the accumulated weight of the evidence favors something done later in period style.

Make no mistake, the Meditations binder was good. Even the endpapers are period-appropriate leaves removed from an old book. This binding was absolutely the product of a skilled craftsperson with a thorough understanding of period styles—and perhaps the product of a binder with the skill and patience to make their own finishing tools.

~Pat

Post link

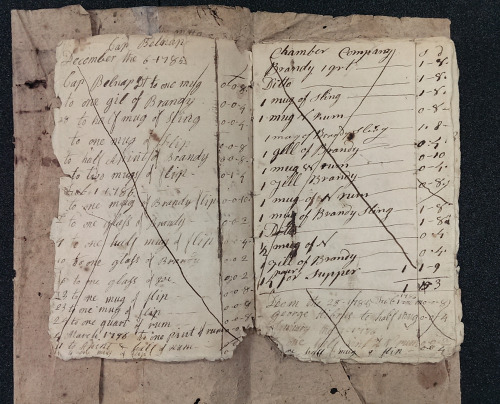

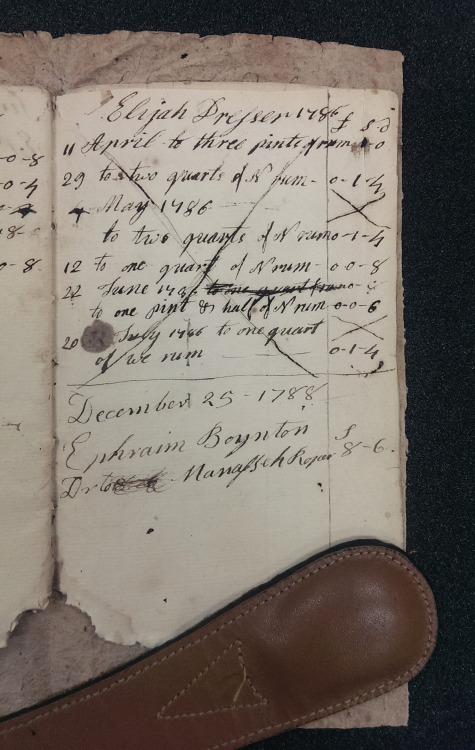

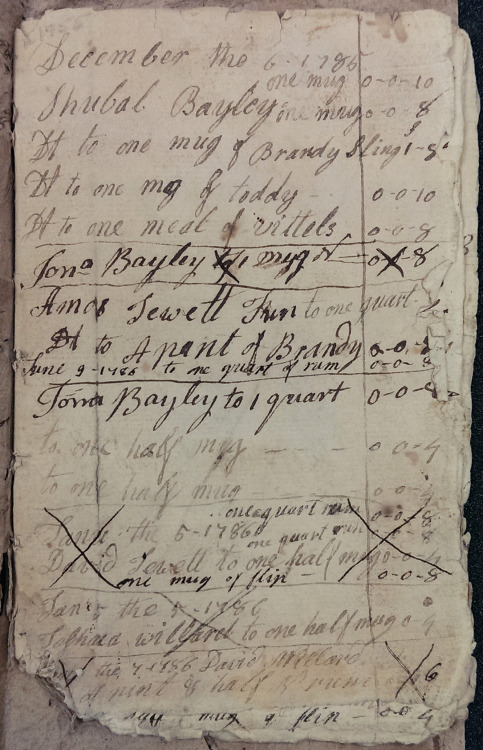

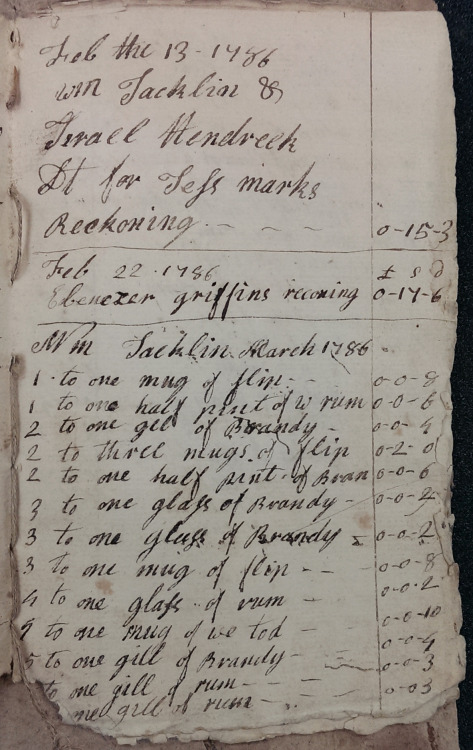

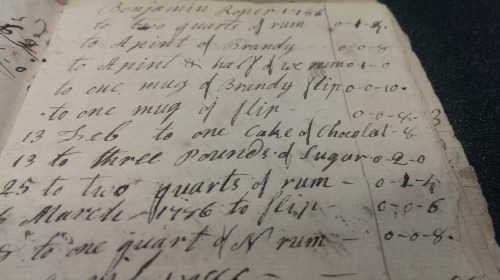

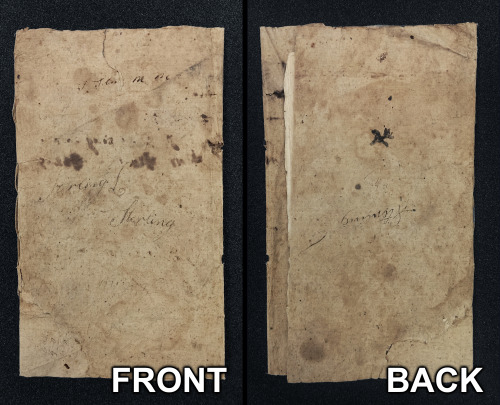

Picture the scene: A bustling New England tavern, December 1785. Two patrons sit at the bar, swapping war stories and discussing nascent U.S. political philosophy over mugs of… of what, exactly?

MSU Special Collections recently acquired an early American tavern keeper’s account book that can help answer that question—recording what American revolutionaries and their contemporaries were drinking (and eating) over two centuries ago.

Dating from December 1785 through 1788, this tavern keeper’s logbook tracks the sale of brandy, rum, flips, slings, toddies and other contemporary beverages, illustrating the drinking habits of 18th century New Englanders. There are some entries for meals, and for sales of salt, sugar, and other commodities (as well as “one cake of chocolate”), but unsurprisingly the most popular fare was liquid in nature.

While the barkeep’s name remains anonymous, it is easy enough to trace the ledger to Sterling, Massachusetts—the town’s name is written several times across the tattered paper covers, and a number of personal names penned in the book can be found in Sterling’s early town records.

This manuscript account book is in amazingly good shape considering its age (231 years old) and heavy use, and it gives us a rare insight into the types of transactions that must have been commonplace at shops and taverns of the period. So join us in raising a mug of brandy flip (or a slice of chocolate cake, if you prefer) in honor of our recent acquisition!

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b11889851~S39a

~Andrew

Post link

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link

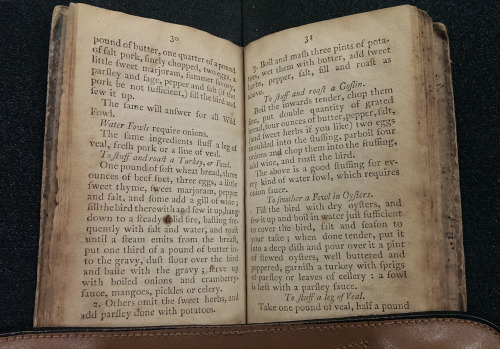

First published in 1796, American Cookery by Amelia Simmons is considered the first true American cookbook, with recipes for such indigenous foods as pumpkins, cranberries, and cornmeal. Cookbooks published here previously were English in origin with food and recipes written for English audiences.

American Cookery is the bedrock for all important cookbook collections and MSU Special Collections is fortunate to hold several early editions of the work, including the second printing of the first edition, published in 1798. We recently acquired another—the 1808 edition—published in Troy, New York.

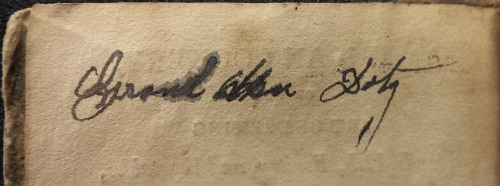

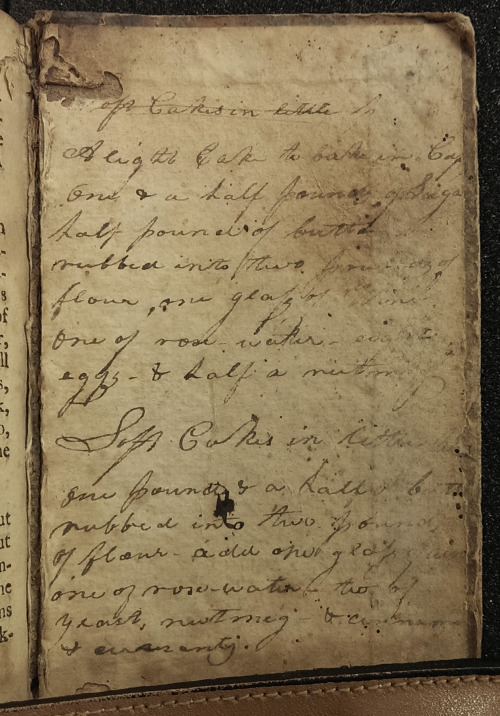

Any early edition of this important work is special, but this particular volume is extra special for its provenance. Boldly written on the inside of the front cover is the name “Ruth Doty,” who moved to Detroit from Troy, New York with her merchant husband Ellis Doty (a descendant of Edward Doty who came to America on the Mayflower). This volume was published three years after their marriage in 1805, so perhaps this was one of Ruth’s first cookbooks—and most likely journeyed with her over ten years as she and her growing family made their way west to Detroit by the early 1820s.

In addition to the inscription of Ruth Doty, there are other ownership clues in the book. On the inside of the back cover there are two manuscript recipes for cakes, in a different hand than Ruth’s. Most intriguing of all, on the verso of the title page is what looks like the name of another Doty… Can you make out what it says?

One can only speculate as to whether the cookbook stayed in the Doty family after Ruth’s death in 1866 at the age of 82, but its remarkably good shape despite its age, travels, and use clearly suggests that whoever owned the book realized its importance and historical value.

~Peter

Post link

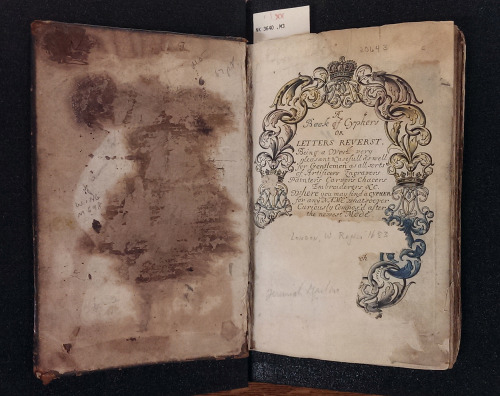

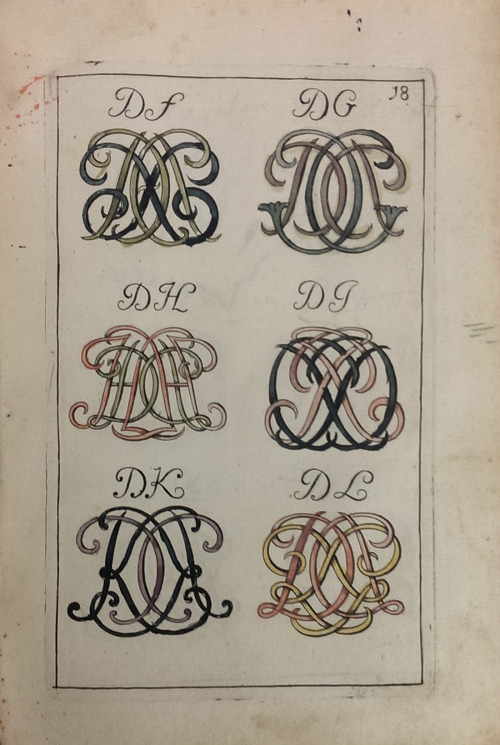

A Book of Cyphers, or Letters Reverst (1683)

Our somewhat damaged copy of this 17th century work on cyphers or monograms features wonderful hand-coloring throughout. Some of the colors have faded with age, but this artistic personal touch still adds a layer of beauty to this fascinating little book.

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1118994~S39a

~Andrew

Post link

Scared of everything

Italy, 04/12/2019

Coming Soon…

Renovations are wrapping up, and shiny new shelves for archives and rare books are being installed in a new secure and climate controlled space.

We. Can’t. Wait. To. Fill. Them. Up.

Post link

Let’s find more PRIDE in our special collections, all year. (Within and not just on our stuff.)

Post link

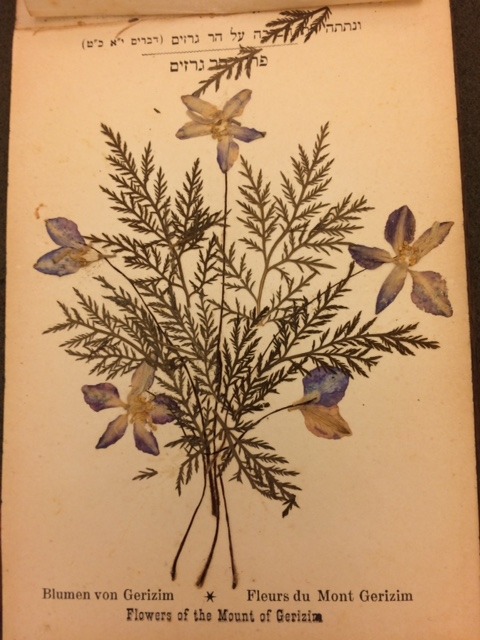

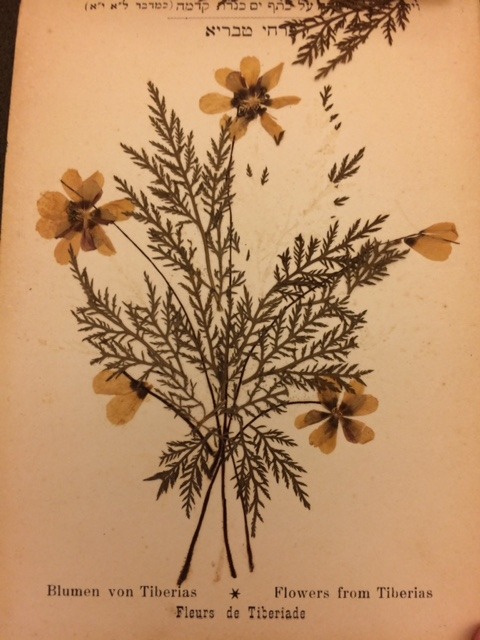

Some very lovely (but very dry & dead) flowers for you.Flowers of the Holy Landcontains pressed flowers arranged into mini bouquets or ornamental displays and their identifying names. Bound into a small souvenir volume, these dainty displays are still looking pretty good.

Post link

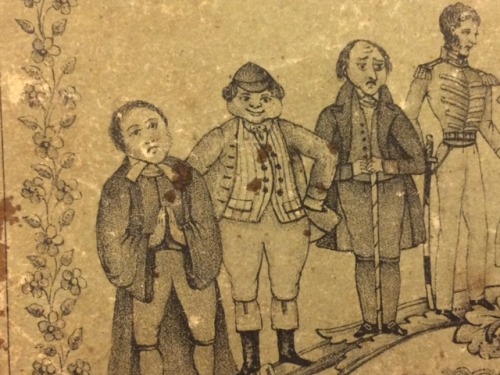

It’s game time ladies! Discover your path to true love in this 1830s board game. Eight admirers compete to win the hand of the heiress. Perhaps a peer is your type? Or maybe a dandy or a squire? A sailor, soldier, lawyer, parson, and doctor are additional options. Each suitor is assigned a separate path to the heiress.

Each path starts with a bit of 19th c. humor. Courtship with the doctor begins with a heartache, the lawyer with “a brief suit,” and the parson with “a humble prayer.” Stages along the relationship path include agitation, displeasure, hope, disappointment, (more) agitation, hesitation, anger, and fear. Despite the clear rockiness of the relationship, the heiress always accepts her suitor in the end.

The game’s cover includes sketches of the dashing fellows.

Post link