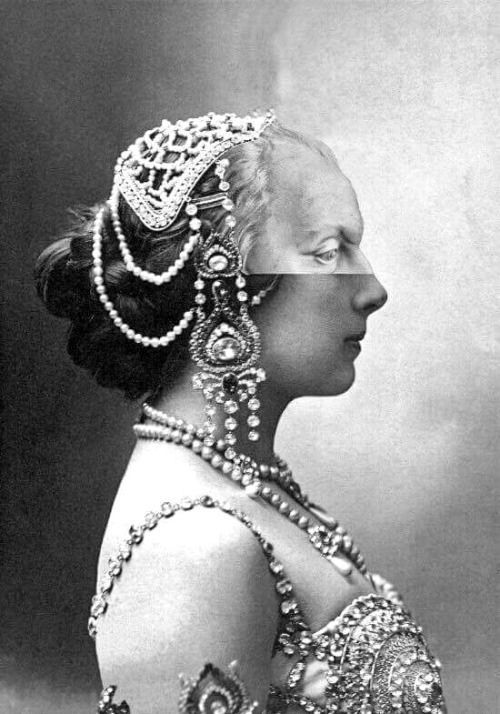

#spectral hag

“As the days went on, the statue appeared to move around the home seemingly of its own accord, muddy footprints began to manifest on the floor, and the pungent scent of stagnant pond water filled the house. On the seventh day, they saw her crouched in the shadows of the living room: The Crone, a horrifying apparition with an emaciated body and eyes that shined in the darkness.”

Post link

“Spectral evidence” is a form of evidence based upon dreams and visions. It was admitted into court during the Salem Witch Trials by the appointed chief justice, William Stoughton. The booklet A Tryal of Witches, taken from a contemporary report of the proceedings of the Bury St. Edmunds witch trial of 1662, became a model for and was referenced in the Trials when the magistrates were looking for proof that such evidence could be used in a court of law.

Spectral evidence was testimony that the accused witch’s spirit, called a spectre, appeared to the witness in a dream or vision, sometimes as they would appear normally, other times as a foul hag, a swarm of insects, or a black cat or wolf. Thus, witnesses and accusers would testify that “Goody Proctor bit, pinched, and almost choked me,” and it would be taken as evidence that the accused were responsible for the biting, pinching and choking; even though they were elsewhere at the time.

Thomas Brattle, a merchant of Salem, made note that “when the afflicted do mean and intend only the appearance and shape of such an one, say G. Proctor, yet they positively swear that G. Proctor did afflict them; and they were allowed to do so; as though there was no real difference between G. Proctor and the shape of G. Proctor.”

Reverend Cotton Mather argued that it was appropriate to admit spectral evidence into legal proceedings, but cautioned that convictions should not be based on spectral evidence alone, as it was possible for the Devil to take the shape of an innocent person.

A Mare was believed to be a spectral visitor: a dark spirit that takes the form of an animal, a beautiful lover, a disfigured hag, or a demon which visited men in their dreams, and rode their chests, bringing on bad dreams or “nightmares,” and dragging life out of them.

Aside from demons, Mares could also be witches, who were known to take on the form of an animal when their spirits went forth from their bodies in trance, called a “fetch”. These were usually small animals which left the body through the mouth, such as: moths, bees or wasps, birds, or frogs, and acted as a vessel for the disembodied soul, and as such was directly linked to the person’s fate and well-being. The fetch could also take the form of a larger animal, usually a hare, a cat or dog, a horse, or even an oxen. The fetch became corrupted when weaponized and projected forth for nefarious purposes, such as to cast malefic witchcraft or blight, or to drain the vitality of others, and becomes a foul hag or mare; akin to a projection of the ugliness of the person’s true essence. Moths especially were associated with the Mare, and often finding them dead where one sleeps was believed to indicate her visitations.

The word “Mare” comes, through the Middle English mare, from Old English mære,mare, or mere.

These in turn come from Common Germanic marōn,from which are derived the Dutch: “nachtmerrie”, and German: “nachtmahr”. The -mar in the French word “cauchemar,” meaning "nightmare,” is borrowed from the Germanic through the Old French mare. The word may ultimately be traced back to the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root mer-, meaning "to rub away” or “to harm”. Hungarian folklorist ÉvaPócs endorses an alternate etymology, tracing the core term back to the Greek μόρος (Indo-European moros), meaning “death”.

In Norwegian and Danish, the words for “nightmare” are marerittandmareridt respectively, which can be directly translated as “mare-ride”. The Icelandic word martröð has the same meaning: -tröð, from the verb troða, meaning “trample”, “stamp on”, related to “tread”. Whereas the Swedish mardröm translates as “mare-dream”.

The Mare was also believed to ride horses, which left them exhausted and covered in sweat by the morning, or sickened to the point of death. She could also entangle the hair of the sleeping man or beast, resulting in “marelocks,” or “hag knots”. This is closely related to the lore surrounding Hag-Riding.

A Ward Against The Mare

The German Folklorist Franz Felix Adalbert Kuhn records a Westphalian charm or prayer used to ward off mares, from Wilhelmsburg near Paderborn:

Hier leg’ ich mich schlafen,

Keine Nachtmahr soll mich plagen,

Bis sie schwemmen alle Wasser,

Die auf Erden fließen,

Und tellet alle Sterne,

Die am Firmament erscheinen!Here I am lying down to sleep;

No Night-Mare shall plague me

Until they have swum through all Waters

That flow upon the Earth,

And counted all Stars

That appear in the Firmament!