#salem witch trials

This might be a long shot but when I first heard foundations of decay and the line about how we’ll press and press till you can’t take it anymore, I thought about the Salem witch trials and how Giles Corey, the only man executed in them, was pressed to death, and then I remembered that Gerard Way has recently become a witch

This might be a long shot but when I first heard foundations of decay and the line about how we’ll press and press till you can’t take it anymore, I thought about the Salem witch trials and how Giles Corey, the only man executed in them, was pressed to death, and then I remembered that Gerard Way has recently become a witch

While researching the Salem Witch Trials, early English folk magic, and modern psychic practices for my upcoming dark fantasy series, my world has become a lot more… magical. Despite my best efforts, I can’t bring myself to believe wholly in magic (though I envy those of you who can!), but I’ve started to notice how these practices I’m studying survive in our modern, logical, technology-centered…

In Memory of those who died in the Salem Witch Hysteria of March 1692 - April 1693

Bridget Bishop

An older woman, Bishop had a reputation for gossiping and promiscuity, but when it came to witchcraft, she insisted to her judicial accusers that “I have no familiarity with the devil.” Nevertheless, Bishop was the first convicted witch hanged on what later became known as Gallows Hill.Sara Good

After her first marriage to an indentured servant left her deep in debt, Good married a laborer who worked in exchange for food and lodging, and the two eked out a meager existence in Salem Village. She was among the first suspects identified by the female children when they were questioned by magistrates in February 1692. Good protested her innocence, but officials insisted upon questioning her young daughter, and the child’s timid answers were construed as proof of Good’s guilt. Good was pregnant at the time of her conviction, and officials stayed her execution until she could give birth. The infant died in prison, and in July 1692, Good herself was hanged. Defiant to the end, Good’s final words were a warning to her tormentors: “If you take my life away, God will give you blood to drink!”Elizabeth How

The Ipswich woman was a kind soul who tenderly took care of her husband John How, who was blind. Nevertheless, something about her aroused others’ ire. Neighbors accused her of causing both their cows and their young daughter to die after they quarreled with her, and when she sought to become a member of a local church congregation, neighbors and kin opposed her. They subsequently experienced a spate of injured animals and other bad luck, which they interpreted as supernatural acts of revenge. In court, her own brother-in-law, Captain John How, accused her of killing his sow and inflicting upon him a painful numbness in his hand that made it impossible for him to work. She was also accused of sending her spectral form to attack a young girl and attempt to drag her into Salem pond. “God knows, I am innocent of anything of this nature,” she testified. But even though other witnesses vouched for her character, she was convicted and executed.Susannah Martin

A widow in her late sixties, Martin was the wife of a blacksmith and the mother of eight. In the 1670s, she previously was accused of witchcraft and infanticide, but her husband had successfully countered the charges by suing her accusers for slander. By 1692, however, he had died, and when 15 of her neighbors accused her of bewitching them or causing their farm animals to die, she had to confront the charges alone. Some historians have speculated that the accusations against Martin were linked to an inheritance dispute in which she was involved. Deeply religious, she comforted herself by reading “her worn old Bible” in jail as she awaited execution.Rebecca Nurse

An elderly woman in ill health and a respected member of the church, Nurse was among the second wave of suspects accused by the children. In her initial court hearing, Nurse protested her innocence, but when her youthful accusers cried out in fake pain and performed contortions to suggest that they were being tormented by her, prosecutors took her impassive reaction as a sign of guilt. She was bound over for trial and executed.Sarah Wildes

As a young woman, Wildes was considered glamorous and forward, and rumor had it that she had once engaged in illicit sex. The accusations of witchcraft against her actually began decades before the Salem witch trials, when she married a widower, John Wildes, which raised the ire of his first wife’s family. The sister of Wildes’ first wife, Mary Reddington, accused Sarah Wildes of bewitching her, prompting John Wildes to threaten a slander suit unless she stopped. When one of Sarah Wildes’ new stepchildren, Jonathan Wildes, began to behave strangely, some took it for demonic possession, and the suspicions against Sarah Wildes continued to simmer. In 1692, things finally boiled over. Wildes’ son Ephraim was a local constable in Topsfield, and protested her innocence when she was arrested by his superior, Marshal George Herrick. One witness fingered her as being part of a coven of specters who whispered at the foot of a dying child’s bed, while others accused her of telekinetically sabotaging their ox cart after they borrowed her plow without her permission. Yet another testified that after quarreling with Wildes, she felt an apparently spectral cat walk across her in the middle of the night. Bizarre as the case against her was, Wildes was convicted and executed.Rev. George Burrough

The only Puritan minister to be indicted and executed in the witch trials, Burrough was accused by Andover and Salem Village residents of being a ringleader and priest of the devil in the witch coven. Part of the evidence against Burrough was his exceptional physical strength, which was viewed as a sign of satanic assistance. Puritan inquisitor Rev. Cotton Mather, who suspected Burrough of being a Baptist and deviating from Puritan practices, attended his trial and urged the jury to convict him, which it did. When Burrough was on the ladder to the scaffold, he gave an impassioned speech protesting his innocence, and concluded by reciting the Lord’s Prayer—which, supposedly, witches were unable to do. His conspicuous religious fervency prompted some of the onlookers to shed tears and wonder if a terrible mistake had been made.Martha Carrier

This victim of the witch hunt is best remembered, perhaps, for being denounced by one of the inquisitors, Rev. Cotton Mather, as a “rampant hag.” The daughter of one of the founding families of Andover, MA, Carrier was married to a servant and the mother of four children. She was an independent, strong-willed person who didn’t like to defer to those who imagined themselves as her betters, and their dislike may have led to her becoming a target of the accusations. Carrier was fearless enough to denounce her youthful accusers. “It is a shameful thing that you should mind these folks that are out of their wits,” she admonished the court. Unfortunately, that didn’t save her from execution.George Jacobs, Sr.

A twice-married father of three in his early seventies, Jacobs was accused by one of his servants, Sarah Churchill, and by his own granddaughter, Margaret. Both of them had been fingered as witches and may have been trying to save their necks by implicating others. Others, however, soon came forward to join them, including women who claimed that Jacobs’ spectral projection had beaten them with a walking stick. But the most damning evidence, in the minds of his inquisitors, was a slight protuberance on his right shoulder that they believed to be the “witch’s teat” that the devil gave to those who’d made a covenant with him. Jacobs offered an unusual defense, arguing that although he was innocent, the devil may have taken his form to commit mischief. The court, however, decided that such shape-shifting could only have occurred with his consent, and he was condemned to death and executed.John Proctor

After inheriting a substantial fortune from his father, Proctor went on to become a successful farmer, entrepreneur, and tavern keeper. Unfortunately for him, he made the mistake of criticizing the young girls who were accusing witches, saying that if they were to be believed, “we should all be devils and witches quickly,” and recommended that they be whipped or even hung for their lies. After being falsely accused by their servant Mary Warren, Proctor and his wife were arrested in 1692. The sheriff went to their house and seized their goods and provisions, and sold off his cattle, leaving the Proctors’ children without a means of support. Proctor petitioned the court to move his trial to Boston, or at the very least, to change the magistrates, because the locals “have already undone us in our estates, and that will not serve their turns without our innocent blood.” It was to no avail. Proctor was convicted and executed in August 1692. His wife was spared because she was pregnant.Martha Cory

Another respected church member who was among the second wave of suspects accused by the children. She was hanged in September 1692.Mary Esty

Some historians’ accounts alternately spell her name as Easty or Eastey. The sister of fellow defendant Rebecca Nurse, Esty insisted in court that “I am clear of this sin” and that she had prayed against the devil “all my days.” Her demeanor was so convincing that even her questioner, magistrate John Hawthorne, was moved to turn to Esty’s accusers and ask, “Are you certain this is the woman?” They responded by writhing and screaming in feigned demonic possession, but nevertheless, Esty was released from jail. In the days that followed, however, one of her accusers appeared to fall ill, and two of the others claimed that they had seen Esty’s specter tormenting her. Esty was arrested once again, and this time she was convicted and hanged.Ann Pudeator

The twice-widowed mother of six, who worked as a midwife and nurse, inherited property from her second husband. In male-dominated colonial New England society, a self-sufficient professional woman was contrary to what was perceived as the rightful order of things, and that may have made her a target for witchcraft allegations. The testimony of witnesses—including a girl who claimed Pudeator had tortured her by impaling a voodoo doll, and another who accused her of shape-shifting into a bird—was augmented by a constable’s discovery of “curious containers of various ointments” in her home. (The latter, apparently, were either foot oil or grease that Pudeator used to make soap.) Despite her protestations of innocence, she was condemned to death and hanged.Samuel Wardell

Born in Boston, Wardell was a carpenter who followed his brother Benjamin to Salem to build houses. He was one of the few, and perhaps the only, defendant who actually had dabbled in magic, when he occasionally amused his neighbors by playing at telling their fortunes, a practice that was outlawed as black magic by the Puritans. Nevertheless, Wardell’s bigger crime may have been marrying a younger widow, Sarah Hawkes, in 1673. Her sizable inheritance—combined with his carpentry work—made the couple conspicuously affluent in a society where petty resentments and envy often blossomed into suspicions that someone had satanic assistance. After his arrest in 1692, Wardell—perhaps in an effort to save himself—conceded that he had agreed to a contract with the devil, who had promised to make him wealthy, and even confessed to evil deeds that he hadn’t been accused of. He later tried to recant, but it was too late. In September 1692, he was hanged.Alice Parker

The wife of John Parker of Salem, she was arrested in May 1692 after being accused by the same servant who fingered John Proctor and his wife. Accused of “sundry acts of witchcraft, she was tried in September 1692, and convicted and hanged shortly afterward.Mary Parker

A wealthy widow from Andover, she apparently was unrelated to Alice Parker but was related to one of the other suspects, Frances Hutchins. Parker and her daughter Sarah were arrested and accused of witchcraft as well. When she entered the courtroom at her trial in September 1692, several of the young female accusers fell into writhing spells, even before her name was announced. Once witness testified that she had seen Mary Parker’s spirit, perched high on a beam above the court, at one of the hearings in Salem. Parker was convicted and hanged shortly afterward.John Willard

Willard, a sheriff’s officer who lived in Salem, was ordered to bring in several of the accused. He declined, apparently out of a belief that they were innocent. As a result, he was himself accused. After initially escaping arrest in Salem by fleeing to Nashawag, about 40 miles away, he was taken into custody and put on trial in August 1692. The girls who claimed to have been afflicted by witchcraft testified that a spectral being that they called “the shining man” had materialized and prevented Willard’s specter from cutting one of their throats. Willard was found guilty and hanged shortly afterward.Wilmot Redd

Also known as Wilmet Reed, she was the only Marblehead resident to be condemned for witchcraft. Known locally as “Mammy,” Redd was an eccentric with a volatile temper, and liked to argue with her neighbors. Among other crimes, she was accused of sending her spectral doppelganger to Salem to torment one of the young girls who instigated the witch hunt. She was arrested, brought to Salem for trial, and then hanged in September 1692, in the final wave of executions.Margaret Scott

Born in England in 1615, Scott moved to New England with her parents at a young age and married a struggling tenant farmer, Benjamin Scott. The couple had seven children, only three of whom lived to adulthood. After her husband died in 1670, Scott lived off his meager savings until they were exhausted. In her old age, she was forced to beg for support from her neighbors and passersby to survive, which made her a target of resentment and probably led to her arrest. At Scott’s trial, witnesses testified that she had visited them in spectral form and choked and pinched them. She was found guilty and hanged in September 1692, in the final wave of executions.Ann Foster

In 1692, when a woman named Elizabeth Ballard came down with a fever that baffled doctors, witchcraft was suspected, and a search for the responsible witch began. Two afflicted girls from Salem village, Ann Putnam and Mary Walcott, were taken to Andover to seek out the witch, and fell into fits at the sight of Ann Foster. Ann, 72, a widow of seven years, was arrested and taken to Salem prison. A careful reading of the trial transcripts reveals that Ann resisted confessing to the ‘crimes’ she was accused of, despite being “put to the question” (i.e. tortured) multiple times over a period of days. However, her resolve broke when her daughter Mary Lacey, similarly accused of witchcraft, accused her own mother of the crime in order to save herself and her child. The transcripts reveal the anguish of a mother attempting to shield her child and grandchild by taking the burden of guilt upon herself. Convicted, Ann died in the Salem jail after 21 weeks on December 3, 1692, before the trials were discredited and ended.Source: Wikipedia & National Geographic

Post link

Rip Bridget Bishop. June 10th 1692

The first, of many, to be tried and excecuted for Witchcraft during the Salem Witch Trials.

We honor you every day, gone but never forgotten.

On This Day In History

May 14th, 1878: the last witchcraft trial in the United States is held in Salem, Massachusetts. Lucretia Brown accused of Daniel Spofford of attempting to harm her by his mental powers. The case was dismissed by the judge.

Out-of-Salem witch accusations are beginning to pick up speed, as more witches from nearby Gloucester and Marblehead, as well as Reading, are being sought out. Nicholas Frost and Joseph Emons are targeted.

Jane Lily, when examined, vehemently denies any knowledge of witchcraft, nor of any of the specific crimes she is accused of, including killing a local man in a fire. In a voice choked with emotion, she cries that she will only speak the truth, “for God is a god of truth”, but her accusers merely shriek that the Devil has her throat. Not only does Lily have several afflicted accusers, but also confessed witch Samuel Wardwell, to argue against, and it is futile.

Mary Coulson, daughter of accused witch Lydia Dustin, is likewise hauled in; her accusers claim that she has been tormenting them ever since her mother was put in prison. Coulson’s daughter Elizabeth escapes arrest.

Margaret Prince is accused of bewitching Mary Sargent; Sargent’s husband says that he has heard that she also afflicts his sister, but knows nothing of her personally. Other accusers are unable to speak when she is near, then say that they see the Black Man gesturing to a coffin on the table before her.

The final examinant of the day, Mary Taylor, is likewise accused of being part of the same fire that Jane Lily supposedly set. She is told that her neighbor Mary Marshall accuses her, to which she replies, “There is a hot pot now, and a hotter pot prepared for her”.

Meanwhile, the court begins to summon witnesses for the coming trials, which are set to start first thing the next morning.

Two more witches, now in Gloucester, are apprehended before the week is out - Elizabeth Dicer and Margaret Prince.

When Mary Parker is questioned by the magistrates, she tries to deflect blame from herself, claiming that another woman in Andover has the same name. Her accusers protest that she is the culprit, however, including Mary Lacey and Mary Warren, who is brought before her with a pin sticking out of her hand and blood dripping from her mouth. William Barker Jr., the 14-year-old confessed witch, points to Parker and confirms that she is one of his kind.

Suspected witches from Andover continue to be dragged into the meeting house, whole families having been arrested together.

William Barker Jr., aged 14, has joined his father and sister in confessing to witchcraft. When first apprehended, he fails to give a straight answer; he cannot say if he bewitched anyone as he has no memory of it. After several days in prison, however, he agrees that he is a witch, although he “hath not been in the snare of the devil above six days”. A black dog and a black man (both clothing and skin) had accosted him and had him sign a book giving his life to them. He tries to deny being baptized by the devil, but his accusers fall into fits, forcing him to change.

Stephen Johnson, also 14, tells a similar story.

Samuel Wardwell is brought in with his daughter and daughter-in-law, all of whom eventually confess. Wardwell claims that he had been discontented with his work and the difficulty of life, and had been lured into the devil’s snare by cursing animals in his field and fortune telling. When the local constable interjects that his notoriety goes much further back, Wardwell admits that the devil had come to him years earlier in the form of several cats in the shape of a man, luring him in the midst of sexual temptation. Mercy, his daughter, was likewise tempted in a moment of weakness - having been bullied by the other girls, who claimed she would never be loved, she had attempted to drown herself, and thus fell into temptation. Daughter-in-law Sarah Hawkes is also questioned. Like the others, she confesses when her accusers confront her directly, admitting to attending witch’s sabbaths with Goody Carrier, but stating that she had never afflicted anyone before the previous night.

While witches continue to be interrogated, an official summons goes out for a new round of men, “forty good and lawful men of the freeholders and other freemen of your bailiwick duly qualified to serve on the jury of the trials of life and death at the next session of their Majesties’ Special Court of Oyer and Terminer in Salem upon Tuesday the sixth day of September next at nine in the morning”.

Elizabeth Johnson Sr. is led on by the magistrates, owning that her daughter had made her and witch and answering an increasingly long list of leading questions. Like the others, she describes lavish witch’s meetings, travelling by horse and on poles, and being baptized in the river. Her specter is allowed to strike others she says; her spirit leaves her body, leaving her in a “cold, dumpish, melancholy condition”.

More Andover witches are being arrested, tortured, and interrogated. Elizabeth and Abigail Johnson are apprehended while Mary and William Barker are dragged in for questioning.

Mary Barker, aged thirteen, under pressure, finally accuses Goody Johnson of turning her into a witch. Her father, knowing that his cooperation will make things easier for him, claims to have been under Satan’s spell for three years.

Mary Marston also confesses readily.

John Jackson Sr. and Jr. are the next accused to be interrogated. The younger man immediately blames his aunt, but his father vehemently denies any wrongdoing. One by one, his accusers are brought into the room to witness him, and each are struck down in his presence. When Mary Warren slams herself into a bench hard enough to draw blood from her head, Jackson is removed from the meetinghouse.

The accusations are coming faster now, and the constables in nearby towns can hardly keep up. William Barker, Mary Marston, Mary Barker, John Jackson Jr. and Sr. of Andover are called out and arrested.

Another of the Andover accused, twelve year old Mary Bridges, is brought to Salem before Magistrate Hathorne, and, agreeing to the now common-knowledge bargain, confesses to witchcraft. In the spring a yellow bird had appeared to her outside and offered her fine goods if she would afflict her neighbors; although she did, she had received none of the Devil’s promises.

Mary’s mother Sarah initially resists her interrogation, but eventually cries out that she too had signed the Devil’s book. There are two hundred witches in Massachusetts, she says, and she knows of only one innocent man imprisoned.

Her sisters Hannah and Susannah Post are likewise brought before the magistrates and they too, eventually confess, “afterwards”, according to the magistrates. None of the officials have yet heard anything from the governor regarding John Proctor’s allegations of torture.

As the executions show no signs of stopping, some of the wealthier prisoners begin to make escape plans using their connections. Hearing that their trial has been scheduled and new evidence is being collected against them, Philip and Mary English enlist more liberal ministers Joshua Moody and Samuel Willard to help them slip out in the middle of the night on Sunday. By the time anyone thinks to check on them Monday morning, the Englishes are already in New York. Sheriff George Corwin immediately goes to their farm, illegally seizes the English’s property, and uses the over one thousand pounds, some of which is squandered and some that goes to jail upkeep.

Nathaniel Cary also helps his wife Elizabeth escape from prison around this time with the help of friends.

Margaret Jacobs is still wracked with guilt over sending her grandfather and her minister to the gallows. but gaining their forgiveness has given her courage to speak out further. She summons the jailer and dictates a letter to her father, who has not yet been accused.

“The reason for my confinement is this: I having, through the magistrates threatenings, and my own vile and wretched heart, confessed several things contrary to my conscience and knowledge, though to the wounding of my own soul, the Lord pardon me for it. But oh! the terrors of a wounded conscience who can bear. But blessed be the Lord, he would not let me go on in my sins, but in mercy I hope so my soul would not suffer me to keep it in any longer. But I was forced to confess the truth of all before the magistrates, who would not believe me, but ‘tis their pleasure to put me in here, and God knows how soon I shall be put to death. Dear Father, let me beg your prayers to the Lord on my behalf, and send us a joyful and happy meeting in Heaven.”

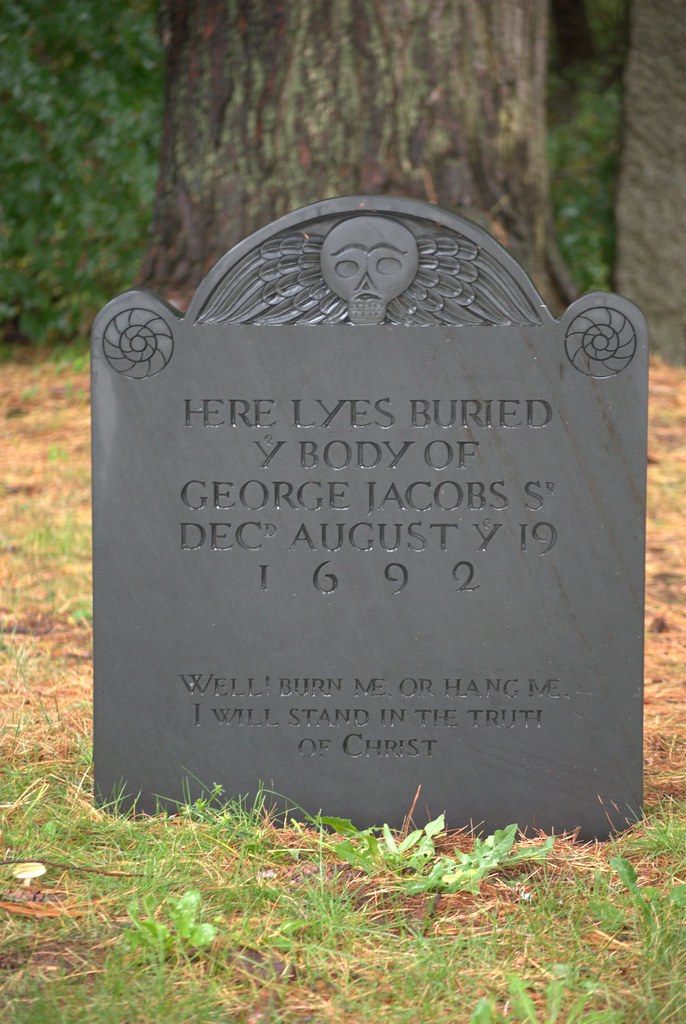

The grave of George Jacobs

On the night of August 19th, 1692, George Jacobs’s family secretly removed his remains from a crevice in the side of Gallows Hill and buried him on his own land. His remains were uncovered by a family member in the 1950s and were finally laid to rest under a 17th century style slate gravestone in the Nurse family cemetery on August 19 1992, the 300th anniversary of his death.

The stone is marked with his defiant words to the court:

“Well! Burn me or hang me, I will stand in the truth of Christ.”

George Jacobs’ homemade canes.

During his witchcraft trial, Jacobs’s servant accused him of beating her with these sticks, and others claimed that his specter did so as well. Jacobs tried in vain to insist that it was impossible for any of this to have happened because he was 72 years old with arthritis and could barely stand on his own without the canes, let alone hit someone with them.

Post link

Five witches are loaded into the cart bound for Gallows Hill: George Burroughs, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs, John Proctor, and John Willard. While in prison, Elizabeth Proctor had announced that she was pregnant, and local midwives confirm it before her execution. She is allowed to carry the child to term before being hanged.

It is likely that John Proctor made an impassioned speech to the crowd before his execution, but whatever he said is overshadowed by Reverend Burroughs.

After being lead up the ladder, Burroughs is asked one last time if he wishes to make a confession. Instead, he gazes serenely at the crowd and asks them to pray with him. The bewitched girls mutter that the Black Man is speaking through him, but they are shushed. As his accusers stand in stunned silence, Burroughs preaches his last sermon. Over the next several minutes, he proclaims his innocence and his forgiveness of the accusers, and concludes with a flawless recitation of the most fundamental Puritan prayer, the Lord’s Prayer.

Failure to remember basic prayer is a cornerstone of witchcraft accusation; by Cotton Mather’s own teachings, this is proof that Burroughs is not a witch. The crowd, shouting and moved to tears, begins to beg the executioner to let Burroughs down. Unfortunately, Mather himself has come up from Boston to witness the hanging and quiets the crowd to save his reputation. Mather shouts above the noise that Burroughs’s preaching in meaningless, as he has never been formally ordained. Also, he reminds them, “the devil has often been transformed into an angel of light”.

Burroughs, followed by the others, are hanged and the bodies are thrown into the crevice of the hill. As a final injustice, Burroughs’s clothes are considered too fine to waste, and he is stripped and put into second hand breeches before being hastily disposed of.

George Jacobs’s family later removes his body and buries in by his home.

Two more witches are brought into custody: Frances Hutchins and Ruth Wilford.

That night, unable to sleep through the guilt and impending executions the next day, Margaret Jacobs begs to see Reverend Burroughs. In his cell, she breaks down and tells Burroughs that her accusations against him and her grandfather were false; she had accepted the magistrates bargain and sold them out in exchange for her own life. Sobbing, she begs Burroughs’s forgiveness. He spends the night praying with her and the others who are to be executed the next morning.

Reverend Noyes offers to pray with John Proctor, but only if he will confess. Proctor refuses to speak to him.

One of the confessed witches of the previous day, Elizabeth Johnson, has named Daniel Eames as a fellow witch. Eames is dragged in for questioning.

The afflicted girls accost him, telling him of the various times he has afflicted them, but Eames denies this. He instead asks the magistrates to pray for him.

“I desire in the presence of Jesus Christ that you would pray for me that I may speak the truth,” he says. “He that is the Great Judge knows that I never did council with the devil and do not know anything of it. I never signed no book nor never saw Satan or any of his instruments that I know of.”

The accused witches from the day before are continually questioned. Because they have confessed, their testimony is needed to name and convict other witches. At this point the magistrates have been offering plea bargains to their prisoners: confess, and you will be kept as a source of information. Fail to confess, and you will be convicted and hanged.

Martha Carrier’s daughter Sarah, now in custody, is examined and immediately confesses to witchcraft. She has been a witch since she was six years old, she says. Her brother Thomas likewise confesses, recounting that his mother had threatened to kill him if he did not sign the devil’s book, and had baptized him as a witch in the river. Another witness claims that she saw this event and was likewise seduced into being baptized.

The most anticipated trials are held for the spectators of Salem Village: outspoken husband and wife team Elizabeth and John Proctor and Satanic minister George Burroughs are brought before the jury.

Several petitions have been sent to the court in defense of the Proctors, including mention of the girl who had falsely cried out Goody Proctor’s specter in the tavern before her examination, but these are overshadowed by spectral evidence, physical evidence in the form of poppets, and documented servant-beating.

Mary Warren and many of the other bewitched girls recount spectral beatings by the couple while contorting themselves during the proceedings. The specters of the couple tormented the girls during the original examinations, the jury is reminded, and they continue to do so now. Warren leads the group in screeching about pinches, pricks, bites, and burns. Other witnesses have seen these specters at work as well.

More damaging is John Proctor’s insistence in the insanity of his fellow Villagers. Several times he has been heard badmouthing the afflicted girls, calling them spoiled and in need of a beating. His skepticism goes beyond the immediate proceedings, as questioning the girls’ motives can be seen as questioning religious doctrine, as well as the credibility of influential officials who have believed the case from day one.

Despite his prestigious background, Burroughs is thought by many to be the “head actor at some of their hellish rendezvous, and one who had the promise of being a king in Satan’s kingdom”. Like the other men, Burroughs has a long history of domestic violence and surprising strength, in addition to damning testimony by the ghosts of his dead wives and the many accused witches of his being in charge of black Sabbaths with red wine and bread.

Burroughs’s ministerial background haunts him as witnesses come forward to warp Biblical texts in his name, such as Mercy Lewis, who testifies that, like Satan to Jesus, Burroughs had taken her to a high place and offered her all the kingdoms of the world. She would not yield, she said, even if thrown on a thousand pitchforks. Ann Putnam Jr., likewise, writhes on the floor and cries that the “little black man” is shoving his demonic book at her. Burroughs already has a history of living among, if not fraternizing with the Indians, and Putnam has already accused him of bewitching soldiers fighting them.

As the accused tell their stories, they frequently fall into fits and are unable to speak. When confronted about this, Burroughs acknowledges that the devil may be hindering them, but seems confused as to why.

Burroughs has a final retort, however: when asked to defend himself before the jury, he produces a written speech, in which he states that having heard the accusations against him, he is now convinced that “there neither are, nor ever were, witches, [and} that having made a compact with the devil, can send a devil to torment other people at a distance.” With this simple sentence, Burroughs shatters Puritan theology: not only does he deny spectral evidence, but witchcraft itself. If witches do not exist, neither does the devil. If the devil does not exist, neither does God.

All three are found guilty.