#uzbekistan

A shy one ! They keep on cumming without their husbands, with me !! Hope to make more of a slut out of her! To be continued …..

submit your nudes wives! husbands will never know ;)Post link

Bukharian Jews (also Bukharan Jews) stem from Central Asia and speak Bukhori, a northern dialect of Tajiki language. The origin of Bukharian Jews can be traced back to the destruction of the Northern Israelite and Judean kingdoms. Exiled Jews left in droves, mostly northern and western, but a smaller number settled in the east, in what was then the Persian Empire. Many of them made the city of Bukhara their home, hence the name “Bukharian” Jews. In the 600s, the Arab conquest of Central Asia began and Islam became the dominant religion of the region. It was already evident here that the Bukharian Jews were taking steps to protect themselves from assimilation. They strove to live together in Jewish neighborhoods, and lived under their own rule with a community chief, called a kalontar. Despite varying levels of self-imposed segregation, cultural exchange did take place, and one can see many similarities in music, dance, food, and dress between Bukharian Jews and other Central Asian populations.

During the spread of Islam in the 7th and 8th centuries, control of Bukhara was transferred between many different Islamic administrations. In 1219, the Mongols, led by Genghis Khan, conquered Bukhara, pillaging and burning the city to the ground, destroying the Bukhara Jewish community. In the beginning of the 16th century, Central Asia was invaded and conquered by nomadic Uzbek tribes who established strict observance of Islam and religious fundamentalism. During this period many Jews were forced to convert to Islam. The town of Bukhara eventually became a center of Jewish life in Central Asia, absorbing Jews fleeing cities located in the midst of battles between warring Islamic parties. More Jews relocated to Bukhara when the city of Samarkand was destroyed by an earthquake in the 16th century.

Because of their ability to speak numerous languages, Bukharian Jews often acted as liaisons between various groups of foreign traders. Some Jews were financiers, others were known for their crafts, especially the dyeing of cloth, and silk weaving. Wealthier Jews invested in caravans which traveled the Great Silk Road.

In the middle of the 19th century, many Bukharian Jews began to move to Palestine, and there they established the well known Bukharian Quarter (Sh’hunat Buhori), that still exists today in Jerusalem. They had arrived by railroad and on animals, many bought land in Jerusalem either to live in, or to visit; some desired to hold onto the land in the event of a pogrom or persecution from which they would have to flee from their native land. At this time, many Jews began to support many of the Russian influences on Central Asia as a way to escape the persecution they had faced under the Muslim governments. This compliance with the Russian influence put them at odds with the Islamic majority, and there were riots against the Jews for most of the time between 1918 and 1920.

In the 19th century, Bukharian Jews were joined by Jews from other parts of what would become part of the Soviet Union. These new arrivals noticed the distinctive splendor of the costumes and customs of the Bukharian Jews. The woman’s costume included a loose-fitting ikat silk gown in shades of rose or violet, over which was worn an elaborately-embroidered coat with kimono sleeves, called a kaltshak. Head-covering was either an embroidered cap or tulle scarf with a jeweled forehead ornament. Other jewelry included bracelets, earrings and coin necklaces. Until modern times, Bukharian Jewish men wore a caftan-like garment called a djoma, secured at the waist by a cord girdle. Over the djoma was worn a long, loose-fitting flared coat. The usual head-covering was made of Astrakhan, short curled lamb hair, or a handsomely embroidered kippah. While Jewish men were forbidden to wear the turban, the rest of their clothing did not differ from Bukharian Muslim dress of the period.

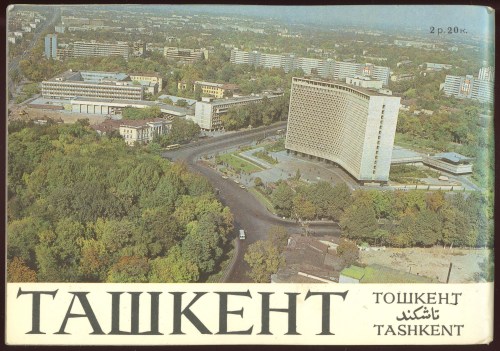

Since the creation of the independent Republic of Uzbekistan in 1991, a growing number of Bukharan Jews have left the country due to the rise in Muslim fundamentalism and the poor economy. More than 70,000 Jews have left the country since its inception, and have moved to Jerusalem and the United States. Large Bukharan Jewish populations are located in Jerusalem and Queens, New York. The Jewish community of Bukhara is now around 3,000 and, in Samarkand, there are approximately 2,000 Bukharan Jews.

xxxxxx

Post link

This fall, the George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum will open two new exhibitions that showcase textiles from its collections: China: Through the Lens of John Thomson (1868-1872) (opening September 19) and Old Patterns, New Order: Socialist Realism in Central Asia (opening October 10).

These photos give you a sneak-peek inside our conservation lab, where conservators have been hard at work preparing mounts to display the textiles chosen by the curators. These mounts are carefully crafted to both aesthetically compliment the objects and to safely account for their fragility and condition needs.

From top to bottom:

- When not on display, many textiles are stored in special mats; their standard size facilitates their transfer between the storage space and conservation lab. Once in the lab, their design allows for an easy move onto the display mounts. Textile fragment with cicadas and flowers of the four seasons, China, 19th century. The Textile Museum 1992.18.2; Gift of Dr. Edmund Bowles in memory of Lois W. and Edward L. Bowles.

- Each mount is custom-fit to the object and is covered by hand with layers of archival padding and exhibition fabric. Here, Conservator Lisa Anderson uses threads to square the perimeter and help center the textile on the mount. The threads will be removed once the object is secured.

- This silk embroidered sleeve for the China exhibition is laid down and carefully sewn to its display mount using fine silk thread. Very thin insect pins help keep the embroidery in place during the sewing process. Sleeve band, China, 19th century. The Textile Museum 1965.65.3a.

- Conservation intern Diana Van Wagner is putting the final touches on a hat mount for Old Patterns; this foam insert will be invisible to the viewer but will play a major role insuring that the hat will hold its shape and be well supported for all the time it is on display.

- At any given time, the conservation staff is working on various projects. In the foreground Chief Conservator Esther Méthé is verifying the final placement of a scarf for Old Patterns, while in the background Lisa is working on the underpinning she sewed to add volume to a coat slotted for display in the same exhibition. Woman’s scarf, Uzbekistan, late 19th to early 20th century. The Textile Museum 1995.8.1. Gift of Mr. Laron Larian, Tel Aviv.

Photos by Zachary Marin / The George Washington University.

Post link

The magnificent Royal Suzani tapestry, size is 20’ - 14’ (6х4,12 m), embroideress master Madina Kasimbaeva.

The exhibition ‘The Birth of Suzani’, which explores the traditional art of Uzbek embroidery, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Post link

LAKAI-SHAHRISYABZ Suzani, Uzbekistan, First half 19th century. 255 x 216cm (8’ x 7’) Rippon Boswell auction, Sold for: €143,000

Post link

In-door and out-door costumes of Sart (uzbek) women. Turkestan. Central Asia. 1880s. F.Orden.

Post link

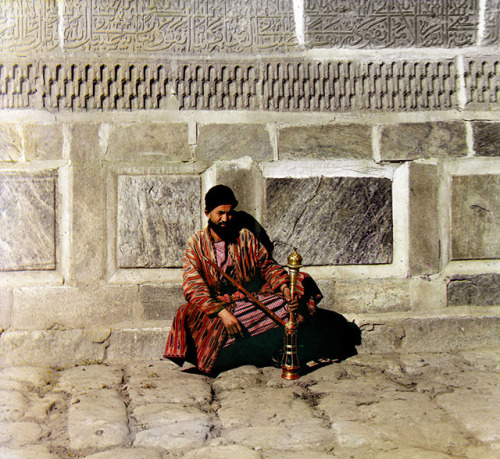

Shah-i-Zinda (Uzbek: Shohizinda; Persian: شاه زنده, meaning “The Living King”) is a necropolis in the north-eastern part of Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Ensemble includes mausoleums and other ritual buildings of 9-14th and 19th centuries.

Post link

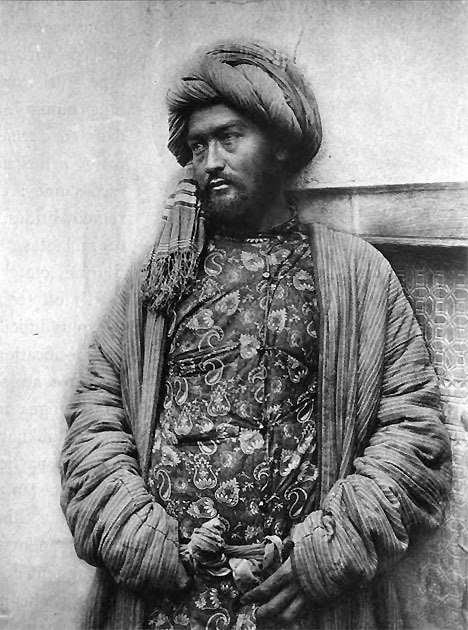

Amazing textiles and style…. Tajik man, near Bukhara, Central Asia. 1898—1899. Very nice old bohemian style, caftan, turban.

Таджик (окрестности Бухары). Здесь и далее фото Г. Крафта.

Post link

Uzbekistan has one of the worst human rights records on Earth. The government forces citizens to work in annual cotton harvests, leading the Global Slavery Index to estimate that 4% of the country is enslaved, and the reason you don’t hear about it is because the US government is not only not trying to overthrow them, it is not even sanctioning them, and in fact the State Department states that “Uzbekistan is important to U.S. interests in ensuring stability, prosperity, and security in the broader Central Asian region, and the U.S. has provided security assistance to the country to further these goals.”

my parents lived in uzbekistan and they said that if they didn’t pick enough cotton, they couldn’t attend school

I hope that it’s okay if I add more informations on this.

International and Uzbek law explicitly prohibit forced labor and specifically prohibit a government from forcing a person to work against his or her will under threat of punishment or penalty.

Yet according to official statistics, the government imposes contracts on more than 45,000 farms per year to deliver annual quotas of silkworm cocoons. Although some of the farms are specialized silk farms, the vast majority are small-scale farms that also produce cotton, wheat, livestock, or vegetables. Given the short but intensive production cycle of silk cocoons, to meet their silkworm cocoon quotas many farmers rely on family members’ labor, others offer in-kind goods in exchange for their neighbors’ labor, and some hire workers, either with written or verbal contracts.

In addition to the official number of farms that produce silk, local authorities also require numerous public organizations such as mahalla committees, schools and hospitals to produce cocoons. Where the regional or district hokim also imposes silk cocoon quotas on public organizations, this occurs completely informally and without a contract. The government exploits the vulnerability of farmers and public sector employees to force them to produce cocoons and the system relies on rural poverty since many rural people agree to help farmers produce cocoons in return for in-kind payments of basic items needed for survival, such as firewood and cooking oil.

The government imposes quotas on producers for cotton, wheat, and silk, and producers must sell to the state at the official procurement price. The government wields tremendous power over farmers: it can take a farmer’s land or assign him less desirable land; government-owned or controlled monopolies supply all agricultural inputs; and the government controls all financial transactions related to farming.The government prohibits farmers from growing vegetable gardens on leased agricultural land, although such gardens provide a crucial means for farmers to feed their families and earn cash. The gardens put farmers in violation of their lease agreements, giving hokims additional leverage over farmers. Public sector employees such as teachers, school officials, and medical workers, and other people dependent on the government for livelihood support such as people receiving welfare payments, are also vulnerable to state-orchestrated forced Labor because they fear losing their jobs or support payments.

Batir Zakirov (Ботир Зокиров) - Uzbek Tango

Batir Zakirov was an Uzbek and Soviet singer, painter, actor and a prominent cultural figure, who is considered to be the founder of Uzbek pop music. He was awarded the title of People’s Artist of the USSR at age 29.

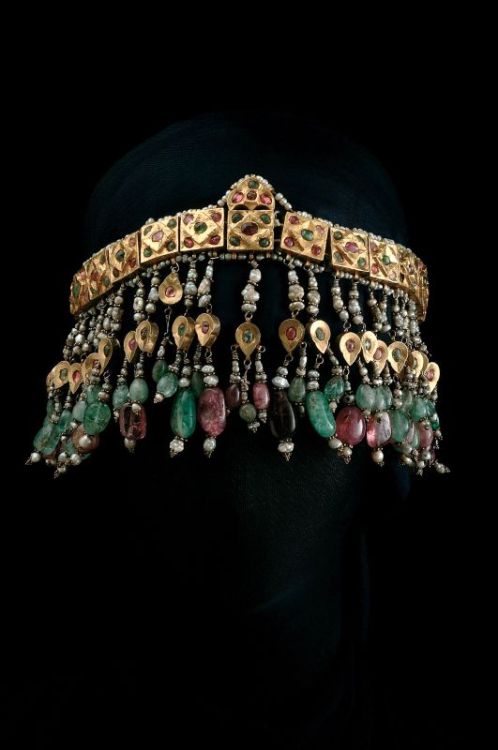

Head ornament of a Jewish bride (balgak), Bukhara, Uzbekistan, late 19th century.

Before the wedding, well-to-do Bukharan Jewish families would invite a goldsmith to their house, where he would make the jewelry for the bride, living there until the dowry preparations were completed. The jewelry was made of gold, colorful semiprecious stones, and pearls, some local and others imported, mainly from Russia. The jewelry remained the bride’s private property throughout her life and was bequeathed to her daughters upon her death. This forehead ornament is a central component in the magnificent set of jewelry worn by Jewish women for holidays and ceremonies.

Post link