#a short description of historic fashion

Fashion Friday: The Power of Plumage

Thedissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 resulted in the creation of fifteen nation-states including Ukraine and Estonia, while 1993 saw the end of communist rule in Czechoslovakia, becoming the Czech Republic and Slovakia. These nations are featured here in my second-to-last fashion plate post with costumes honoring easier days of traditional ethnic dress.

Leo Tolstoy could be argued as the conscience of Russian peasants by his fictional writing in the classic Anna Karenina.Tolstoy was in fact a nobleman and landowner yet he adorned himself in smocks and meager dress, fashioning humility as he wrote of earthly indulgences and subtle sermons on the wickedness of the human condition.

The dress of laborers is also honored in a 1936 Soviet Union publication on a revered textile workerinMiss USSR where a young woman’s 10-hour days and record-breaking statistics on factory looms are lauded as joyful. Her uniform is a black silk blouse and skirt and her profile is documented as “slim” and “little.”

Yet, as with the earliest civilizations there is a place for costume, for adornment that celebrates more than the work of our hands or size of our bodies, whether a farmer’s, a writer’s, or a weaver’s; we yearn for the occasion allowing ornamentation that arouses our senses and inflames our imaginations.

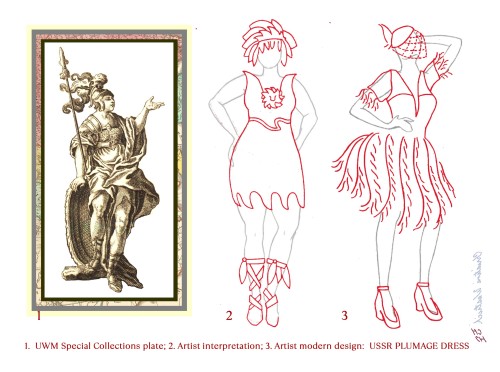

My first fashion plate is titled the USSR Plume Dress, perhaps interpreted by some as a peacock’s egoism; the second plate may be favored by fan-followers of Egon Schiele, while the last crowns brawn and might.

Here is a listing of sources from the UWM Special Collections and the UWM American Geographical Society Library that I have augmented with digital color and outline to emphasize particular details of my inspiration:

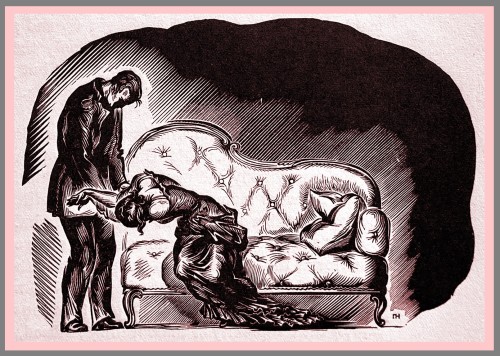

1, 8) Wood-engravings by Nikolas Piskariov as featured in Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina; published in the USSR in 1933 and printed by the Limited Editions Club, respectively titled Anna’s Fall and Head-Piece to Part the Fifth.

2-4) My contemporary designs of the USSR Plume Dress, Estonian Edith Dress, and Czech Crown Dress based on maps from the collection of the UWM American Geographical Society Library that show iconic costumes, respectively titled Russian Empire 1757, published in Augsburg, GE by Augustae Vindel in 1757; Folklore Map of Czechoslovakia, published in Czechoslovakia by the Ministerstvo Informaci in 1948; Parishes of Estonia 2010, published by the AS Regio in 2010.

3) Black and white drawing of Czechoslovakian dress by Belle Northrup in A Short Description of Historic Fashion published by Columbia University’s Teachers College in 1925.

5) Photograph of Dusya Vinogradovo a 21-year old woman dubbed Miss USSR: The Story of a Girl Stakhanovite, the Soviet Union’s leader in weaving production and noted to be every young person’s friend as she was “free and happy”; published in New York by International Publishers in 1936.

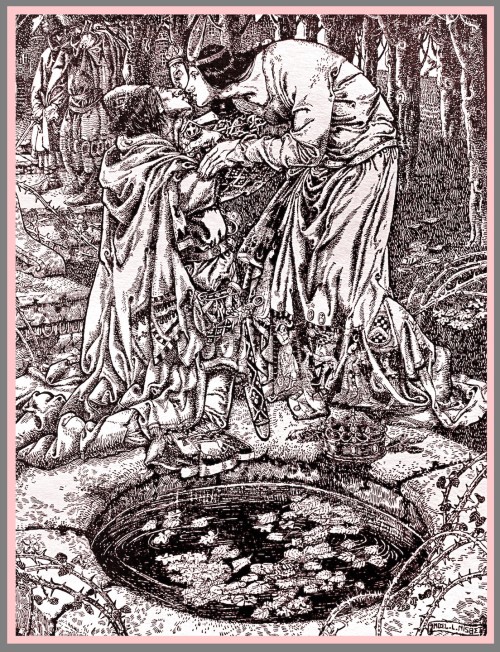

6, 7) Illustrations by Noel L. Nisbet from the collection of Russian Cossack Fairy Tales and Folk Tales, published in London by George G. Harrap & CO in 1916, respectively titled They Came to the Place Where He Had Left Her and His Wife Caressed and Wheedled Him.

Viewmyother posts on historical fashion research in Special Collections.

View more Fashion Friday posts.

—Christine Westrich, MFA Graduate Student in Intermedia Arts

Post link

Fashion Friday: The Mannerism of Michelangelo

The Renaissance period is often synonymous with the greats of Michelangelo, Da Vinci, and young Raphael. These master painters poised “imitation” as preeminent beauty, art as poetry—ut pictura poesis—with Michelangelo arguably harnessing the peculiarities of the human spirit most adeptly in his abstract sprawl of figures, elongating their unseen beauty.

A Renaissance essay on Michelangelo by the nineteenth century art critic Walter Horatio Pater investigates the imagination of the master, calling attention to the artist’s wayward loves-at-first-sight and their contradictions with the sculptor’s mantra of la dove io t'amai prima, or,where I loved you before. Pater argues that it is precisely this paradox that comprises harmony: the delight between the sweet and the strange.

Pater repudiated his own time of the Victorian era, acclaiming the decadence of the Renaissance period as the seizing of life, or more aptly in his own words on living:

…to grasp at any exquisite passion… or any stirring of the senses, strange dyes, strange colours, and curious odours, or the work of the artist’s hands, or the face one’s friend.

It is in his words that we can embrace the unnatural grace of the late Renaissance, the period adorned with the Mannerist style of bold outlines, objects at-play with nature, and form with fantastical animal-humans. This unique style of the Renaissance is attributed to Michelangelo’s successors who desperately tried to imitate his alien elegance.

Hidden in the figures of Michelangelo are these languid features, satyrs in repose, where solemnity and “faces charged with dreams” dictate, as described by Pater. Darting poetic thoughts give us a glimpse of the bittersweet temperament of Michelangelo’s genius. He wrote of his torments in the pagan frivolities of endless quarrelling and his anger at the Gods for loving him so that he reached an age of eighty-eight years.

In all of his years, Michelangelo claimed his figures to be common, austere persons, yet his hand rendered an inherent surprise and energy that future imitators would exploit in quirky forest gods and lovely monsters.

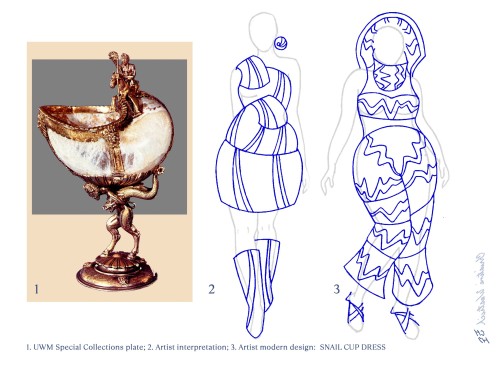

Ergo, my first fashion plate is titled “DRAGON EWER Dress,” odd, but not as eccentric as the last two designs; perhaps you can trace the growth of the outlandish creature in each iteration.

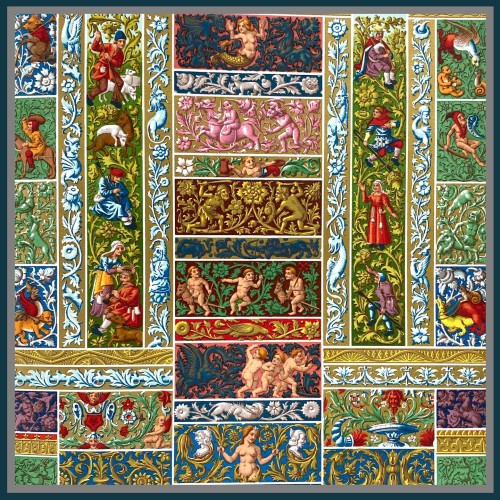

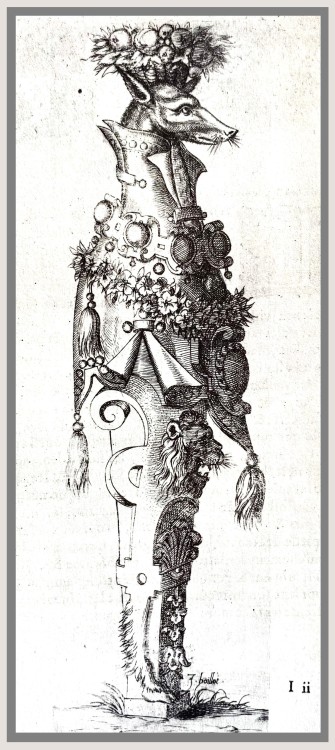

Here is a listing of sources from the UWM Special Collections which I have augmented with digital color and outline to emphasize particular details of my inspiration:

1) A watercolor drawing by (or after) Wenzel Jamnitzer, circa 1575 in the Virtuoso Goldsmiths and the Triumph of Mannerism, published by Rizzoli International in 1976.

2-4) My interpretation and contemporary design of the DRAGON EWER Dress, SNAIL CUP Dress and DAVID TANKARD Dress based on Renaissance period vessels between 1540 to 1590 as published in the Virtuoso Goldsmiths and the Triumph of Mannerism, published by Rizzoli International, in 1976.

5, 6) French Renaissance plates of frieze borders in Rouen prayer books from 1508; and painted enamel work of Limoges under Italian faience between 1520 and 1540 as published in theDas polychrome Ornament: Hundert Tafeln, by P. Neff in 1880.

7) Walter Pater included an image of Michelangelo’s The Holy Family, or, Doni Madonna, at the Uffizi in Florence, Italy in his aethesticism manifesto, The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry, published by the Limited Editions Club, Stamperia Valdonega in 1976.

8) Costume of the early sixteenth century often in velvets (red is common) and embellished with fewels, gold, lace, fur and feathers as illustrated by Belle Northrup in A Short Description of Historic Fashion published by the Teachers College at in 1925.

9) An 1592 engraving by Joseph Boillot titled Et Levrs Antipatie (possible translation Antipathy Lips) as publishedThe Renaissance in France: Illustrated Books from the Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, by the Houghton Library, Harvard University in 1995.

10) A drawing or possible woodcut of indentured lions as published in Thomas Wood Stevens’Book of Words: A Pageant of the Italian Renaissance, published by the Alderbrink Press at the Art Institute Chicago in 1909 for the Antiquarian Society.

Viewmy other posts on historical fashion research in Special Collections.

View more Fashion posts.

—Christine Westrich, MFA Graduate Student in Intermedia Arts

Post link

Decorative Sunday Fashion: The Menagerie of the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are often viewed as the Dark Ages for want of enlightenment and with the Black Death bookending its perilous time. Yet a closer look shows the most novice scholar that the one-thousand-year period from the 5th century to the 15th century is rich with new kingdoms and hybrid cultures.

The Eastern Mediterranean hosted the Roman Empire in its Byzantine lore, while the conquest of the Umayyad Caliphate marched into Northern Africa and Spain, and Western Europe saw the Vikings land on their shores. Civilizations were blended, skilled trades were shared, and manuscripts such as the Divine Comedyabounded.

The Late Middle Ages saw the quick rise and fall of Joan of Arc whose premonitions from the archangel Michael sent her to King Charles VII of France where she became a confidante, military strategist, and gravely feared by the oppressed English rulers. Burned at the stake for heresy and supernatural powers, it was largely a political move to eradicate her power as royal soothsayer.

The ecclesiastical court that judged Joan of Arc may well have been fashioned with mitres just as Roman Catholic leadership was in her modern-era beatification. Original papal tiaras had three tiers representing the authority of sacred orders; silk and linen versions are adorned today and the opulent gold jewels have been shunned and given as symbols to the poor people of the world.

Just as the papal headgear evolved to suit changing sensibilities of society, so too did robewear. The houppelande was worn by both regal men and women of the Middle Ages, and today it is best seen in black on the shoulders of our Supreme Court. The robes were collared in a variety of forms, standing up, V-neck, or perhaps in most recent memory, in the bejeweled style of the dissent collar.

My first fashion plate is titled “Joan of Arc Dress,” armor and flames in style. The remaining designs are similarly inspired; perhaps you can trace the muse through each iteration.

Here is a listing of sources from the UWM Special Collections which I have augmented with digital color and outline to emphasize particular details of my inspiration:

1, 10). photogravures by Lynd Ward in a tale of the Middle Ages, The Cloister and the Hearth, published by the Limited Editions Club in 1932.

2). My interpretation and contemporary design of the JOAN OF ARC Dress based on the illustration of Christian dress in the Middle Ages in Adolf Rosenberg’s Geschichte des Kostums published by E. Weyhe in 1923.

3). My interpretation and contemporary design of the MITRE Dress based on common dress worn by Hebrew and Christian ecclesiastics, illustrated by Belle Northrup in A Short Description of Historic Fashion published by the Teachers College of Columbia University in 1925.

4, 6). My interpretation and contemporary design of the HOUPPELANDE Dress based on garments of the Middle Age illustrated by Paul Louis de Giafferri in The History of French Masculine Costume published by Foreign Publications in 1927.

5) Byzantine costume plate in the United States Work Projects Administration Museum Extension Project publication, Costumes of the World, 100 Hand Colored Plates from Ancient Egypt to the Gay Nineties, 1940.

7) “Indiano” motifs through the Middle Ages, plate XXXVIII in Gli Stili Nella Forma e nel Colore, Rassegna dell’ arte antica e Moderna di Tutti i Paesi, published by Crudo & Co. in 1925.

8) Christian tapestry, plate 57 in Alexander Speltz’s The Coloured Ornament of All Historical Styles, Part I: Antiquity. Leipzig, GE: Baumgärtner, 1915.

9) German expressionist oil painting by Melanie Kent Steinhardt which evokes a common perception of life in the Middle Ages, in The Life and Art of Melanie Kent Steinhardt, published by Rabbit Hill Press in 2002.

Viewmy other posts on historical fashion research in Special Collections.

ViewmoreDecorative Sunday posts.

View more Fashion posts.

—Christine Westrich, MFA Graduate Student in Intermedia Arts

Post link