#costumes of the world

Decorative Sunday Fashion: The Menagerie of the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are often viewed as the Dark Ages for want of enlightenment and with the Black Death bookending its perilous time. Yet a closer look shows the most novice scholar that the one-thousand-year period from the 5th century to the 15th century is rich with new kingdoms and hybrid cultures.

The Eastern Mediterranean hosted the Roman Empire in its Byzantine lore, while the conquest of the Umayyad Caliphate marched into Northern Africa and Spain, and Western Europe saw the Vikings land on their shores. Civilizations were blended, skilled trades were shared, and manuscripts such as the Divine Comedyabounded.

The Late Middle Ages saw the quick rise and fall of Joan of Arc whose premonitions from the archangel Michael sent her to King Charles VII of France where she became a confidante, military strategist, and gravely feared by the oppressed English rulers. Burned at the stake for heresy and supernatural powers, it was largely a political move to eradicate her power as royal soothsayer.

The ecclesiastical court that judged Joan of Arc may well have been fashioned with mitres just as Roman Catholic leadership was in her modern-era beatification. Original papal tiaras had three tiers representing the authority of sacred orders; silk and linen versions are adorned today and the opulent gold jewels have been shunned and given as symbols to the poor people of the world.

Just as the papal headgear evolved to suit changing sensibilities of society, so too did robewear. The houppelande was worn by both regal men and women of the Middle Ages, and today it is best seen in black on the shoulders of our Supreme Court. The robes were collared in a variety of forms, standing up, V-neck, or perhaps in most recent memory, in the bejeweled style of the dissent collar.

My first fashion plate is titled “Joan of Arc Dress,” armor and flames in style. The remaining designs are similarly inspired; perhaps you can trace the muse through each iteration.

Here is a listing of sources from the UWM Special Collections which I have augmented with digital color and outline to emphasize particular details of my inspiration:

1, 10). photogravures by Lynd Ward in a tale of the Middle Ages, The Cloister and the Hearth, published by the Limited Editions Club in 1932.

2). My interpretation and contemporary design of the JOAN OF ARC Dress based on the illustration of Christian dress in the Middle Ages in Adolf Rosenberg’s Geschichte des Kostums published by E. Weyhe in 1923.

3). My interpretation and contemporary design of the MITRE Dress based on common dress worn by Hebrew and Christian ecclesiastics, illustrated by Belle Northrup in A Short Description of Historic Fashion published by the Teachers College of Columbia University in 1925.

4, 6). My interpretation and contemporary design of the HOUPPELANDE Dress based on garments of the Middle Age illustrated by Paul Louis de Giafferri in The History of French Masculine Costume published by Foreign Publications in 1927.

5) Byzantine costume plate in the United States Work Projects Administration Museum Extension Project publication, Costumes of the World, 100 Hand Colored Plates from Ancient Egypt to the Gay Nineties, 1940.

7) “Indiano” motifs through the Middle Ages, plate XXXVIII in Gli Stili Nella Forma e nel Colore, Rassegna dell’ arte antica e Moderna di Tutti i Paesi, published by Crudo & Co. in 1925.

8) Christian tapestry, plate 57 in Alexander Speltz’s The Coloured Ornament of All Historical Styles, Part I: Antiquity. Leipzig, GE: Baumgärtner, 1915.

9) German expressionist oil painting by Melanie Kent Steinhardt which evokes a common perception of life in the Middle Ages, in The Life and Art of Melanie Kent Steinhardt, published by Rabbit Hill Press in 2002.

Viewmy other posts on historical fashion research in Special Collections.

ViewmoreDecorative Sunday posts.

View more Fashion posts.

—Christine Westrich, MFA Graduate Student in Intermedia Arts

Post link

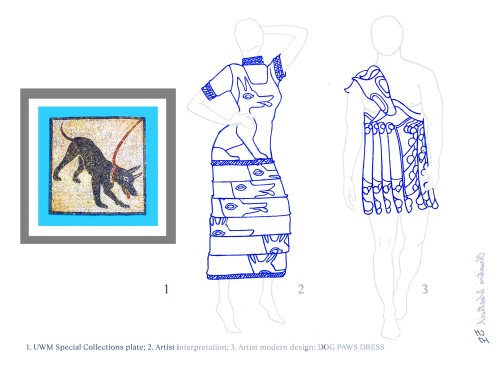

Fashion Friday: Adopt a Pompeiian Dog

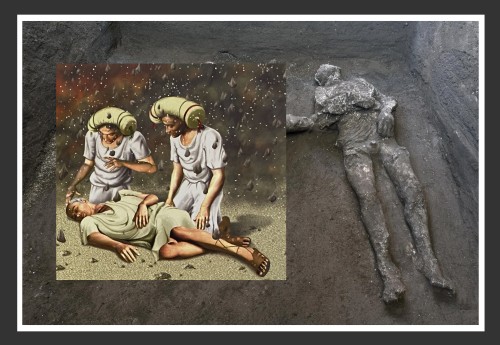

For my fashion inspiration this week, I turned to ancient Pompeii, an urban land that succumbed to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, located on the western coast of Italy, southeast of Naples. The ruins of the city laid buried under ash and earth until 1748 when murals and bodies posed as action figures frozen in time were revealed. While much has been excavatied, today, there are still over 50 acres of land yet to be explored, with growing access to the public as the archeology digexpands.

The allure of Pompeii lies in the catastrophic and immediate deaths of so many who failed to escape, becoming concrete mummies in situ. Recent discoveries in a nearby villa have shown scholars that life in Pompeii was not to be envied, with slavery paramount and social welfare nonexistent.

In spite of the tough Pompeii society, the urban streets were very multi-cultural where theatre was performed in Greek. Street vendors and food stalls provided Roman urbanites with stews of sheep, snail, and fish. Graffiti was found everywhere. Inside one food stall is the mural of a chained dog, with graffiti scrawled on the mural’s painted frame, blaspheming a snack bar owner.

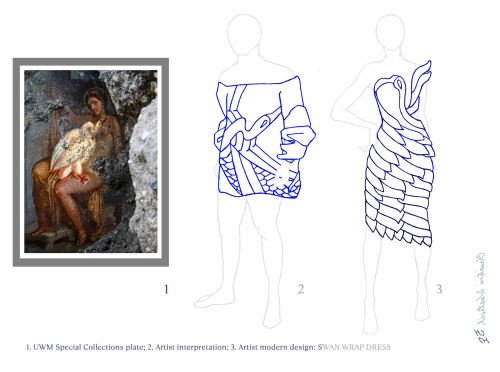

Carnal proclivities were not uncommon in ancient Pompeii. For instance, an excavated fresco of the Spartan queen Leda hints at the everyday homage to the eroticism of mythology. In this story, Leda is seduced and raped by Zeus in swan-form bearing heirs whose power continued the deity tradition of wickedness.

Fortunately, today’s leaders of the Great Pompeii Project are using $137 million of EU funds to reach a vast audience, including Instagram and Twitter followers. Prior to this joint effort, the ruins of Pompeii suffered from environmental overexposure, looting, and Italian red-tape while being nestled in a region of organized crime. In fact, packs of stray Pompeiian dogs are now available for adoption as the archeological site leads modern conservationism efforts by abating tourism blight and corruption traps.

My first fashion plate is titled “Dog Paws Dress,” highlighting the round velvet foot-pads of our furry friends. The remaining designs are similarly inspired; can you spot these single inspirations?

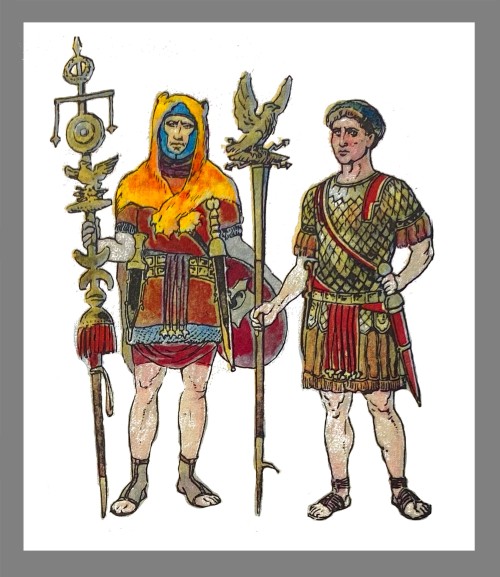

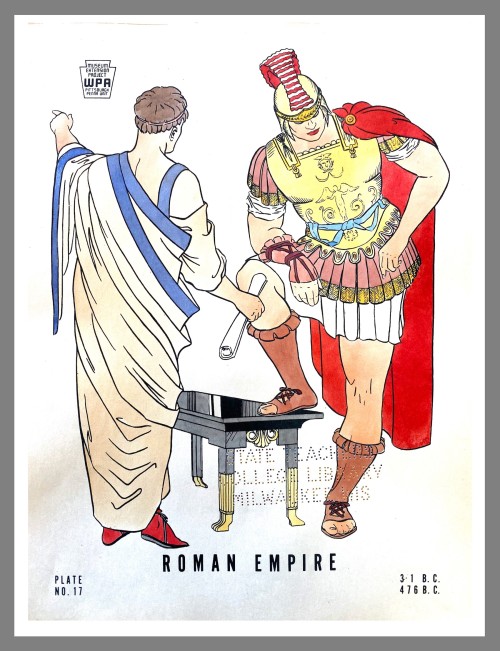

Here is a listing of sources from the UWM Special Collections and the New York Times, which I have augmented with digital color and outline to emphasize particular details of my inspiration:

1, 3, 4, 8). Photographs of ancient Pompeii frescoes and two Roman bodies, published by The New York Times, written by Elisabetta Povoledo, 2018 - 2020. Images 3 an 4 inspired my own designs for the Swan Wrap Dress and the Curly Rooster Dress.

2, 8). My interpretation and contemporary design of the Dog Paws Dress inspired by David Hawcock’s pop-up book, The Pompeii Pop-Up, published by Universe Publishing in 2007.

5) Costume illustration of Roman warriors with animal predator as hooded cloak, in Geschichte des Kostums, published by E. Weyhe in 1923.

6) Woodcut prints by the illustrator Kurt Craemer as published in The Last Days of Pompeii by the Limited Editions Club in 1956.

7) Works Projects Administration illustration of Roman warriors as published in the Costumes of the World, 100 Hand Colored Plates from Ancient Egypt to the Gay Nineties in 1940.

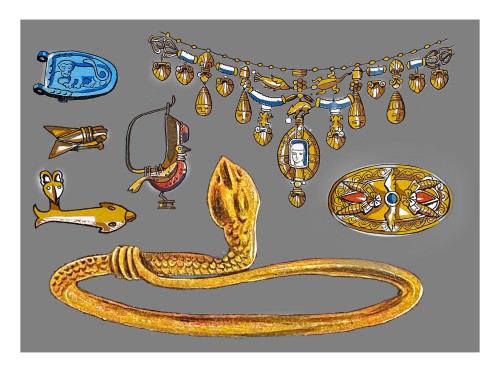

9) Jewelry of the Roman civilization with several animal motifs in Alexander Speltz’s plate collection, The Coloured Ornament of All Historical Styles, Part I: Antiquity, published by Baumgärtner in 1915.

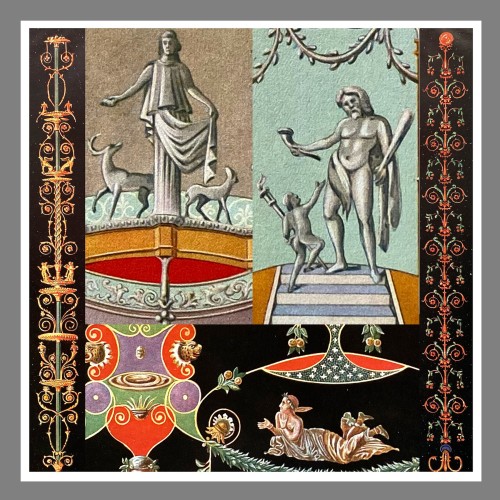

10) Ornamentation of Roman aesthetic as seen in Giulio Ferrari’s Volume 1: Gli Stili Nella Forma e nel Colore, Rassegna dell’ arte antica e Moderna di Tutti i Paesi, published by C. Crudo & Co. in 1925.

Viewmy other posts on historical fashion research in Special Collections.

View more Fashion posts.

—Christine Westrich, MFA Graduate Student in Intermedia Arts

Post link