#african american authors

In graduate school, we had an epic battle over characters’ racial diversity/representation on the page, and craft. Some well-meaning white writers in workshop were including problematic depictions of characters of color in their stories – the “all-seeing,” “magical” black woman, the homeless black man, the perpetual Asian American foreigner. When confronted, I remember that one particularly irascible, intractable white male peer accused us of policing art. “You can write about whatever you want, however you want,” he sputtered. “If I want to write about a triangle on the moon, I should be able to do it. And no one should criticize me for not including black people.” I remember I smiled wryly and said, “Yes, but that doesn’t mean that it will be good art. If you are using problematic and tired racial stereotypes and tropes in your writing, or just writing a flat universe of (white, male, middle-class) characters it doesn’t matter how awesome your triangles on the moon might be: your form is probably pretty lazy, too.”

Needless to say, he didn’t exactly appreciate my commentary.

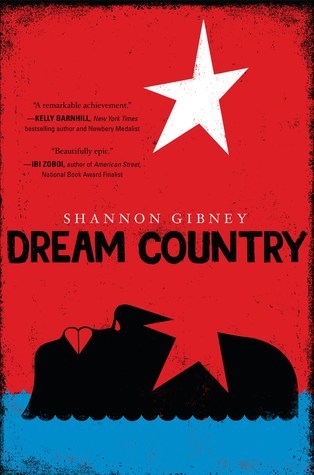

It did, however, force us to confront the relationship between diversity of content, and diversity of form – a topic which I thought I’d pose in this blog post. Quite simply, I’m interested in this question: Does more racial/identity diversity of characters and content necessarily mean more formal diversity? Meaning, are stories that include characters from a variety of racial, ethnic, class, gender, and other identities more likelyto be better written stories, or take more formal risks, or be more formally interesting, than stories with characters with mainstream (read: white) backgrounds? In the course of writing my new book, Dream Country,I certainly found this to be true.

Dream Countryis a sprawling story of colonialism, war, family, and home, and features five narrators on two continents, over 200 years. There was no way to write this novel and do the questions it asks justice without pushing myself out of my formal comfort zone. It could not be your standard one-voice YA novel (not that there is anything wrong with that – my first novel, See No Color, is a YA novel of this variety. But this approach just was not going to work for this particular project). I needed to inhabit the voice of a disaffected teenage Liberian refugee, a 19thcentury African American single mother, a young Liberian revolutionary in Monrovia in 1980, and a modern-day young, queer, African and American writer. I needed all these voices to be distinct, yet compelling, and I needed them to also somehow fit together in the contours of a larger story. Needless to say, my content comfort zone was also deeply challenged in the writing of the book. I am not Liberian, but African American, and balked at the prospect – and responsibility – of representing Liberians on the page. But I realized that this was actually the topic of the novel itself: The chasms and connections between Liberians, Liberian Americans, and African Americans. In my quest to tell this story, I had to attempt to cross these chasms by doing intensive bibliographic and interpersonal research. I read everything I could get my hands on about the colonial period in Liberia; went to Monrovia and interviewed government officials and everyday people about the 1980 coup; and interviewed two gentleman who were generous enough to share their stories of being “sent back” to Liberia from the U.S. by their parents, in their eyes, to save their lives. While I am quite sure that there are still plenty of errors in the book, its formal challenges required me to reach for a new level of excellence in its content – a phenomenon I think may be more common than we realize.

Shannon Gibney is a writer, educator, activist, and the author of See No Color (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), a young adult novel that won the 2016 Minnesota Book Award in Young Peoples’ Literature. Gibney is faculty in English at Minneapolis Community and Technical College, where she teaches critical and creative writing, journalism, and African Diasporic topics. A Bush Artist and McKnight Writing Fellow, her new novel, Dream Country, is about more than five generations of an African descended family, crisscrossing the Atlantic both voluntarily and involuntarily (Dutton, 2018).

Dream Country is available for purchase.

I don’t have a daughter yet, but if I did, I would have taken her to see Wonder Woman. And I’m sure she would have been enamored as much as I was. It’s also safe to assume she’d be a young black girl, and while enjoying the movie, she would instantly know Wonder Woman doesn’t look anything like her. She might even go so far as to ask, “Mommy, I like Wonder Woman, but can I be Wonder Woman?’

The movie was progressive and (for the first part) fun, but its lack of intersectionality made it like many other superhero and fantasy series, in that women of color can only enjoy it to an extent. Wonder Woman didn’t have the diversity I want for empowering my future children. It had the kind of diversity that plucks a few POC at random and throws them into an all-white world, that makes them sidekicks and tokens, that others them. Wonder Woman isn’t the only movie to do this, and plenty of YA fantasy book series do it, too. When I have children of color, I want to be able to give them a fantasy series where they don’t have to ponder why the heroes and heroines never look like them. I don’t want them to feel like they must blend into the mainstream, into whiteness, to be powerful and strong.

My debut novel, The Blazing Star, is about a sixteen-year-old black girl named Portia who travels back in time to ancient Egypt, kicks butt, and saves the world. She also takes her twin sister, Alexandria, and a classmate, Selene, on the journey with her. They, too, are women of color. And smack dab in the middle of The Blazing Star’s cover is Portia’s face looking off in the distance, ready to wield her #blackgirlmagic as she sees fit.

I’m not sure how many other black girls are on the cover of YA fantasy book series, and I’m not sure how many lead their own stories as protagonists. But judging by Lee & Low’s annual research, the number is incredibly low. I was hell-bent on my book series doing what traditional pub is dragging its feet to do—fixing the representation gap—a major component of why I went indie. I received the “can’t connect with the voice” rejections from agents over and over, but knew there was an audience for The Blazing Star. Sure enough, it sold out on release day.

What I love most about the series is that I know my future daughter will never have to ask if she can be Portia. She will just know she can by picking up The Blazing Star and seeing a black girl on the cover. And when the second book in the series, The Falling Star, releases in February 2018, there will be another beautiful black girl on the cover, and my future daughter will know she can be Alexandria, too.

My parents gave me a wonderful (no pun intended) gift thirty years ago. They surrounded me with black dolls and books with black protagonists, which permitted me to see myself not as the Other, but as normal. As a well-rounded, complex person with likes and dislikes and experiences that matter like anyone else’s, and who knew her black skin was beautiful just the way it was. It was my parents’ mission to ground my normalcy in my agency, not in my proximity to whiteness. Perhaps that education, that pedagogy of possibilities, is why I sold my car and put the money toward publishing the first in a YA fantasy series starring teens of color. It’s not a series about tokenism. It’s about agency. It’s a love letter to my fascinating sisters and to my future children. It’s beyond diversity—fantasy or not, at its heart, my trilogy is reality.

Imani Josey is a writer from Chicago, Illinois. In her previous life, she was a cheerleader for the Chicago Bulls and won the titles of Miss Chicago and Miss Cook County for the Miss America Organization, as well as Miss Black Illinois USA. Her one-act play, Grace, was produced by Pegasus Players Theatre Chicago after winning the 19th Annual Young Playwrights Festival. In recent years, she has turned her sights to long-form fiction. The Blazing Star is her debut novel.

The Blazing Star is available for purchase.

In honor of Black History Month, be sure to come to the YA area at Headquarters to check out our amazing selection of fiction and nonfiction books that celebrate the stories and contributions of African Americans.