#black characters

Happy Valentine’s Day!!

Whether you’re celebrating alone, with a partner or two, with friends, or family; I hope you have a great day today!! ❤️❤️

More black fantasy characters plz

I always wanted to draw those princess wake up scenes, but make it a cute black goth girl that just so happens to be a vampire princess

My two main OCs hanging out

- Don’t characterize a Black character as sassy or thuggish, especially when the character in question is can be described in literally ten thousand other ways..

- Don’t describe Black characters as chocolate, coffee, or any sort of food item.

- Don’t highlight the race of Black characters (ie, “the dark man” or “the brown woman”) if you don’t highlight the race of white characters.

- Think very carefully about that antebellum slavery or Jim Crow AU fic as a backdrop for your romance.

- If you’re not fluent with AAVE, don’t use it to try to look cool or edgy. You look corny as hell.

- Don’t use Black characters as a prop for the non-Black characters you’re actually interested in.

- Keep “unpopular opinions” about racism, Black Lives Matter, and other issues pertinent to Black folks out the mouths of Black characters. We know what the fuck you’re doing with that and need to stop.

- Don’t assume a Black character likes or hates a certain food, music, or piece of pop culture.

- You can make a Black character’s race pertinent without doing it like this.

- Beextremely careful about insinuating that one or more of a Black character’s physical features are dirty, unclean, or ugly.

Feel free to add more.

Adding more…

- Be wary of making Black characters seem animalistic, uncivilized, or subhuman in comparison to white characters. Watch out for: comparing us to monkeys, gorillas, chimpanzees, apes, and other animals.

- Words like Negroid, colored/colured, Negro, and the n-word do not belong in the mouths of contemporary characters you want to portray as sympathetic.

- Not all Black people are African American.

- Africa is not a country but the second-largest continent on earth with some 54 different countries with thousands of ethnic groups and 1,500 to 3,000 languages and dialects.

- Resist the urge to make a Black character seem uneducated and ignorant compared to white characters.

- Capitalizing Black shows that you recognize that the word unifying people of African descent, particularly the diaspora, should be described using a proper noun.

- Please, say “Black people,” not “blacks.”

- Give Black characters the same psychological and moral complexity as white men are given by default.

- Make sure that you don’t write a Black character as happily subservient to a white character.

- Understand and show that you understand that Black characters don’t exist to be the caretakers of white characters.

And more…

- Do your own homework instead of expecting, asking, or demanding Black fans to do it.

- Before approaching that Black person you admire so much for being so articulate about race issues (this is sarcasm) to beta read your work: 1) make sure it’s something they’ve expressed interest in doing, and 2) you offer something in return for their time and expertise.

- Be prepared for fans to have issues with what you came up with and open to suggestions.

- Having only one Black character in a story that takes place in a huge city, country, or galaxy looks weird. Really, really weird. Scary weird.

- Don’t use a Black character’s death to motivate a white character.

- Portray Black characters with complex and multifaceted identities. We are more than just Black. We are also women, LGBT, Jewish, disabled, neurodivergent, immigrants, etc.

- There is a huge chasm between hypersexual and desexualized.

- Remember: what’s progressive for a white character is not necessarily progressive for a Black one.

See more of the series on Instagram! @plekien

Black. Colorful. Melanated.

Artist: @plekien on Instagram

See more of the series on Instagram!

Follow on Instagram to see more of the series!

Follow on Instagram to see the series!

More drawings of my skater OCs Buff, Bro, and Brandy! More art on instagram https://www.instagram.com/jgeekie

Post link

Buff, Bro and Brandy new ocs

I created a Draw This In Your Style to encourage people to produce and occupy themselves during this quarantine

video of the process in partnership with wacom - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pz2ivbU6Uvw

Post link

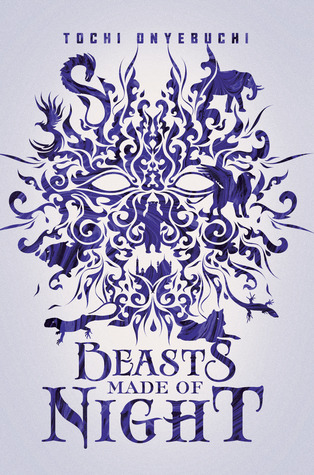

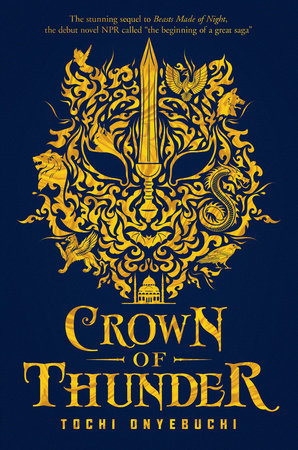

By Tochi Onyebuchi

I was asked recently on a panel what my thoughts were regarding the idea of a black Superman. There was a brief flutter of confusion on the panel, as I and another panelist wondered if some bit of casting news swept us by, but we soon realized the question was more theoretical than anything else. Questions about race and casting and storytelling generally are.

If I recall correctly, my answer was a bit of a deflection. I’d asked the questioner and the audience to, instead of engaging with a non-white Superman, ask themselves why Superman had been made white to begin with. This all-powerful demi-god, who could leap tall buildings in a single bound and who possessed untold amounts of strength, why, if he could already do so many things, was he also made white?

Increasing diversity in storytelling often comes with the built-in assumption that it is writers of color or disabled writers or non-binary writers who are doing the work. These people telling their own stories. The idea is that, the more these stories make it into the marketplace, the more a reader’s eyes will be opened to human possibility, the more likely they are, when they see a person of color or a disabled writer or a non-binary writer, to act with humaneness, rather than hatred. A story from a black author about a black boy makes its way into the hands of a young white reader and, suddenly, the pathway to bigotry is blocked by the empathetic undertaking that is the reading of a book.

But this is supposed to be a group project.

For me, sometimes what increasing diversity in storytelling entails is simply imagining ourselves outside of what we usually see. This can mean black superheroes and female corporate moguls, but it can’t be simple race- or gender-swapping. If the character is not a heterosexual, cis-gendered, white male, let’s make sure they are a fully realized character whose non-whiteness, for instance, isn’t just a splash of paint from an errant paintbrush. When I think back to that question about Superman, I find myself wishing from time to time that I’d answered along these lines, that I’d challenged the audience to imagine what it would look like in 2018 for a black man in America to be able to deflect bullets.

As powerful and as necessary as #ownvoices stories are, I can’t quite let white authors off the hook. In my estimation, it is not enough for them to sit back while the rest of us launch ourselves forward, telling stories that should have already been told, making up for lost time. I think white writers, male writers, should be called upon to interrogate their privilege, and to do so publicly and to do it in their storytelling. For so long, our heroes have looked a particular color. They should ask why, and they should ask it loudly.

Which brings me back to Superman. In many ways, this undocumented immigrant is the embodiment of white, male privilege. No mountain can stop him from getting where he needs to go. People around him are mosquitoes he can flick away with a finger. And, as Clark Kent, he wears glasses he doesn’t even truly need, a fashion accessory more than a health necessity. Of all the forms this alien could have chosen, he chose white. And I think all of us should be asking why.

I wrote Beasts Made of NightandCrown of Thunder not only to imagine a kid the same color as me saving the world, but also to imagine him fighting the awesome anime battles I watched as a teen and being the object of someone’s affection. I wanted to see a black boy fight monsters and be flirted with.

I talk at length about what it can mean, in a cosmic sense, having a hero of color in a world drawn from a non-Western mythos; the implications for diversity; my hopes with my readership. But lost in all of that is this selfish desire I’d had at the very beginning: I’d written Taj’s story for myself as much as for anyone else. Taj wasn’t just a black protagonist. He had my insecurities and my youthful bravado and my halting attempts at caring for my younger siblings. An undercurrent to a lot of questions I get is why did you make Taj black? which is a funny way of saying why did I make Taj me?

Because skin is everything that comes with it. Color carries the context of lived experience.

I don’t ascribe to any “color-blindness” that isn’t diagnosed by a doctor. Someone may insist that it shouldn’t matter what color our heroes are, but I disagree. It does matter. Because skin color has context. It informs our symbols, such that bullets bouncing off the chest of a black man make an entirely different sound than they do bouncing off the chest of a white man, even if the difference is pitched at a frequency only some of us can hear.

Tochi Onyebuchi’s fiction has appeared Asimov’s, Obsidian, and Omenana and is forthcoming from Tor.com, Harper Collins, and Razorbill. His non-fiction has appeared in Nowhere Magazine, the Oxford University Press blog, Tor.com, and the Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy, among other places. His Nommo Award-winning debut young adult novel, Beasts Made of Night, was published by Razorbill in Oct. 2017. Its sequel, Crown of Thunder, was released in Oct. 2018.

His books are available for purchase.

In graduate school, we had an epic battle over characters’ racial diversity/representation on the page, and craft. Some well-meaning white writers in workshop were including problematic depictions of characters of color in their stories – the “all-seeing,” “magical” black woman, the homeless black man, the perpetual Asian American foreigner. When confronted, I remember that one particularly irascible, intractable white male peer accused us of policing art. “You can write about whatever you want, however you want,” he sputtered. “If I want to write about a triangle on the moon, I should be able to do it. And no one should criticize me for not including black people.” I remember I smiled wryly and said, “Yes, but that doesn’t mean that it will be good art. If you are using problematic and tired racial stereotypes and tropes in your writing, or just writing a flat universe of (white, male, middle-class) characters it doesn’t matter how awesome your triangles on the moon might be: your form is probably pretty lazy, too.”

Needless to say, he didn’t exactly appreciate my commentary.

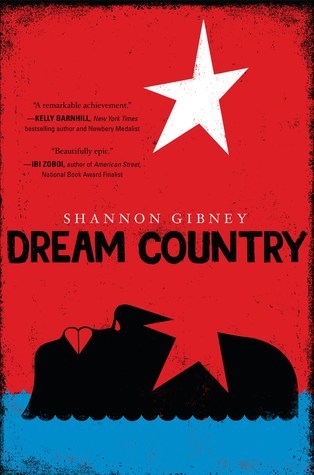

It did, however, force us to confront the relationship between diversity of content, and diversity of form – a topic which I thought I’d pose in this blog post. Quite simply, I’m interested in this question: Does more racial/identity diversity of characters and content necessarily mean more formal diversity? Meaning, are stories that include characters from a variety of racial, ethnic, class, gender, and other identities more likelyto be better written stories, or take more formal risks, or be more formally interesting, than stories with characters with mainstream (read: white) backgrounds? In the course of writing my new book, Dream Country,I certainly found this to be true.

Dream Countryis a sprawling story of colonialism, war, family, and home, and features five narrators on two continents, over 200 years. There was no way to write this novel and do the questions it asks justice without pushing myself out of my formal comfort zone. It could not be your standard one-voice YA novel (not that there is anything wrong with that – my first novel, See No Color, is a YA novel of this variety. But this approach just was not going to work for this particular project). I needed to inhabit the voice of a disaffected teenage Liberian refugee, a 19thcentury African American single mother, a young Liberian revolutionary in Monrovia in 1980, and a modern-day young, queer, African and American writer. I needed all these voices to be distinct, yet compelling, and I needed them to also somehow fit together in the contours of a larger story. Needless to say, my content comfort zone was also deeply challenged in the writing of the book. I am not Liberian, but African American, and balked at the prospect – and responsibility – of representing Liberians on the page. But I realized that this was actually the topic of the novel itself: The chasms and connections between Liberians, Liberian Americans, and African Americans. In my quest to tell this story, I had to attempt to cross these chasms by doing intensive bibliographic and interpersonal research. I read everything I could get my hands on about the colonial period in Liberia; went to Monrovia and interviewed government officials and everyday people about the 1980 coup; and interviewed two gentleman who were generous enough to share their stories of being “sent back” to Liberia from the U.S. by their parents, in their eyes, to save their lives. While I am quite sure that there are still plenty of errors in the book, its formal challenges required me to reach for a new level of excellence in its content – a phenomenon I think may be more common than we realize.

Shannon Gibney is a writer, educator, activist, and the author of See No Color (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), a young adult novel that won the 2016 Minnesota Book Award in Young Peoples’ Literature. Gibney is faculty in English at Minneapolis Community and Technical College, where she teaches critical and creative writing, journalism, and African Diasporic topics. A Bush Artist and McKnight Writing Fellow, her new novel, Dream Country, is about more than five generations of an African descended family, crisscrossing the Atlantic both voluntarily and involuntarily (Dutton, 2018).

Dream Country is available for purchase.

By Sarah Raughley

You know, it’s always cool to read letters from fans of the Effigies series who really appreciate the fact that the titular Effigies are from a racially diverse background—Maia being of mixed Jamaican—American descent, Chae Rin being Korean Canadian, Lake being Nigerian-British and Belle being French. For me it was very important to have the Effigies be as global as the story. This is a world, after all, where any girl in the world could potentially become an Effigy. It wouldn’t make sense, then, for the characters to be an all-white band. When I’m able to do events with kids in the community, for example A Room of Your Own in Toronto where I talked with girls of color at the public library, it’s just phenomenal to see with your own beady little authorly eyes just how important writing diversity is.

And it’s weird because I’ve been told so many times by certain people that there must be a point to the diversity in your book, which I think for them means that your characters’ non-whiteness must be the crux of the story, the world building and/or the characters’ own personal arc. My personal approach to racial diversity is a little different. Of course, our backgrounds inflect who we are in many ways and gives us experiences that others may not have had. However, for my characters, rather than thinking of them as Korean first, or black first, or white first, I think of them as characters first. That means understanding that despite what differences we may have depending on what our ethnicity or nationality is, what makes us human is fundamentally the same. We are all driven by feelings, fears and desires that shape who we are as people. The fact, for example, that I’m Nigerian Canadian doesn’t mean that I somehow respond radically different than someone else when I am in pain or confused or scared for my life, nor does it mean that I’ll react exactly like another Nigerian or Nigerian Canadian would. Certainly, there are cultural behaviors that are learned when you grow up in certain cultural environments, but ultimately, the simple fact of one’s racial makeup cannot be the determining factor of how we act and who we are. Though some would want you to think otherwise, we as human beings have far more in common with each other than with any other species; certainly, regardless of our skin tone or nationality, we have far more similarities than differences.

For me, writing diversity means understanding that cultures and ethnicities are not a monolith. I am not like every other Nigerian or every other Nigerian Canadian or every other diasporic Nigerian living on this planet. I have my own personality, my own presence, my own voice (fun fact, I’ve been told over the phone that I sound like a white girl, which is a lot to unpack) based on how and where I grew up, based on my experiences, and everything else that goes into making someone an individual. If human beings can’t be pigeonholed into certain molds of personality, voice, and behavior based on their ethnic makeup, then neither can (and neither should) characters.

So while diversity is important, one crucial aspect of diversity in books is not approaching it with stereotypical, preconceived notions for how certain characters of a certain race are supposed to act, sound etc. In Fate of Flames and Siege of Shadows, the ethnicities and nationalities of the characters are part of who they are; but as a reader, what you’ll see before their ethnicity is what I always intended for you to see:

Their humanity.

Sarah Raughley grew up in Southern Ontario writing stories about freakish little girls with powers because she secretly wanted to be one. She is a huge fangirl of anything from manga to SF/F TV to Japanese role playing games. On top of being a YA writer, Sarah has a PhD in English, which makes her doctor, so it turns out she didn’t have to go to medical school after all.

Siege of Shadows is available for purchase.

I don’t have a daughter yet, but if I did, I would have taken her to see Wonder Woman. And I’m sure she would have been enamored as much as I was. It’s also safe to assume she’d be a young black girl, and while enjoying the movie, she would instantly know Wonder Woman doesn’t look anything like her. She might even go so far as to ask, “Mommy, I like Wonder Woman, but can I be Wonder Woman?’

The movie was progressive and (for the first part) fun, but its lack of intersectionality made it like many other superhero and fantasy series, in that women of color can only enjoy it to an extent. Wonder Woman didn’t have the diversity I want for empowering my future children. It had the kind of diversity that plucks a few POC at random and throws them into an all-white world, that makes them sidekicks and tokens, that others them. Wonder Woman isn’t the only movie to do this, and plenty of YA fantasy book series do it, too. When I have children of color, I want to be able to give them a fantasy series where they don’t have to ponder why the heroes and heroines never look like them. I don’t want them to feel like they must blend into the mainstream, into whiteness, to be powerful and strong.

My debut novel, The Blazing Star, is about a sixteen-year-old black girl named Portia who travels back in time to ancient Egypt, kicks butt, and saves the world. She also takes her twin sister, Alexandria, and a classmate, Selene, on the journey with her. They, too, are women of color. And smack dab in the middle of The Blazing Star’s cover is Portia’s face looking off in the distance, ready to wield her #blackgirlmagic as she sees fit.

I’m not sure how many other black girls are on the cover of YA fantasy book series, and I’m not sure how many lead their own stories as protagonists. But judging by Lee & Low’s annual research, the number is incredibly low. I was hell-bent on my book series doing what traditional pub is dragging its feet to do—fixing the representation gap—a major component of why I went indie. I received the “can’t connect with the voice” rejections from agents over and over, but knew there was an audience for The Blazing Star. Sure enough, it sold out on release day.

What I love most about the series is that I know my future daughter will never have to ask if she can be Portia. She will just know she can by picking up The Blazing Star and seeing a black girl on the cover. And when the second book in the series, The Falling Star, releases in February 2018, there will be another beautiful black girl on the cover, and my future daughter will know she can be Alexandria, too.

My parents gave me a wonderful (no pun intended) gift thirty years ago. They surrounded me with black dolls and books with black protagonists, which permitted me to see myself not as the Other, but as normal. As a well-rounded, complex person with likes and dislikes and experiences that matter like anyone else’s, and who knew her black skin was beautiful just the way it was. It was my parents’ mission to ground my normalcy in my agency, not in my proximity to whiteness. Perhaps that education, that pedagogy of possibilities, is why I sold my car and put the money toward publishing the first in a YA fantasy series starring teens of color. It’s not a series about tokenism. It’s about agency. It’s a love letter to my fascinating sisters and to my future children. It’s beyond diversity—fantasy or not, at its heart, my trilogy is reality.

Imani Josey is a writer from Chicago, Illinois. In her previous life, she was a cheerleader for the Chicago Bulls and won the titles of Miss Chicago and Miss Cook County for the Miss America Organization, as well as Miss Black Illinois USA. Her one-act play, Grace, was produced by Pegasus Players Theatre Chicago after winning the 19th Annual Young Playwrights Festival. In recent years, she has turned her sights to long-form fiction. The Blazing Star is her debut novel.

The Blazing Star is available for purchase.