#africanindigo

Creating this comic is about more that highlighting traditional Yoruba narratives. It is an exploration of African aesthetics, a blend of western and African artistic techniques. The textile and sculpture arts I use are not simple background, they are an ode to the artistic exuberance of of the Yoruba people and by extension all west african visual art forms. Too often these traditions are belittled as “craft” or “decorative” as opposed to “fine arts”. Their value only recognized when reinterpreted (often misinterpreted) through western contexts. Picasso and Matisse’s asinine obsession with a so called primitive spark ignores the the complex aesthetic and philosophical motivations behind African works of art, ignoring the need to look at it on its own terms. Coolness, spiritual agency, symbolism layered with metaphor within metaphor all are present in the hand and head of the weaver, aladire, carver and potter when they work. The same principles are present in a song, a poem, a proverb or a drumbeat. Whether uttered in Africa and the diaspora, they are imbued with aesthetic and philosophical principles that must be read on their own terms and seen through their own lens. I cannot truly explore the depths of black aesthetics without exploring the power of black arts. That is why it is so important that I make this comic the way that I am making it, To break the delusion of an aesthetic hierarchy that places european ideologies at the top. Support Itan comic today by visiting https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/itan-part-one-africa-art.

Post link

One of the benefits of living and working at the the Nike Centers For Art and Culture is that I get a chance to document her incredibly extensive textile collection. The collection includes Nigerian Textiles (mostly from the Yoruba kingdoms), Raffia cloths from the Kuba federation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Malian “Bogolanfini” Mud cloths and even one beautiful example of of a Ghanaian Kente cloth. The Yoruba made textiles are by far the most extensive part of the collection and include cloths made on both the Women’s (vertical) and Men’s (horizontal, narrow strip) looms. The collection also includes a huge variety Adire (tie and dye and starch resist ) cloths executed on both handwoven and machine woven cloths. The woven textiles include antique textiles woven with hand spun cotton threads, dyed with natural dyes (Mostly indigo with some some camwood dyed warp sections). They also include “Sanyan” textiles woven with the once illustrious beige wild silk collected from the indigenous anaphe moth, as well as textiles woven with imported silks from Asia and synthetic and machine spun cotton, rayon and polyester threads from Europe, Asia and the Americas. There were Indigo robes, shirts, trousers, wrappers and hats. The textiles beauty is only surpassed by their diversity. The pieces are testaments to tradition as well as ingenuity and creativity. There are clothes that could have easily been worn in the ancient courts of Ile Ife and the Ogiso era Benin Kingdom and others that take ancient motifs and execute them with brilliant synthetic or metallic threads, sometimes sewn together with imported textiles to create beautiful and unique pieces speaking to the individuality of the weavers. I began to respect the creators not only as traditional craftsmen, but as contemporary textile artists, working from an African aesthetic tradition.

Below: Examples of textiles using hand spun, hand dyed silk (Sanyan) and cotton threads, as well as machine spun imported threads in imitation of natural dyed threads. The colors and patters used in the AsoOke (Narrow strip cloths) are similar to those created since at least the 16th century, While the striped indigo Women’s loom AsoOfi echo back to cloths made in southern Nigeria dating back the 9th century.

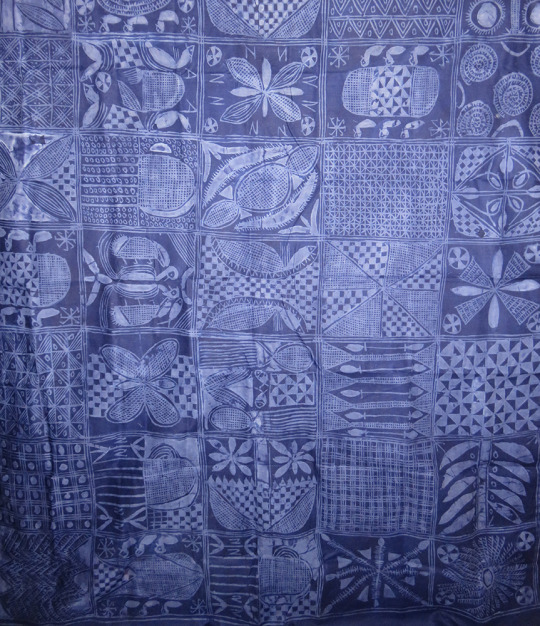

Below are examples of Adire textiles. The top two are representative of the Adire Eleko ( Cassava Starch Resist) techniques developed by Yoruba Women in the early 20th century. Below them are Examples of Adire Oniko (Tie and Dyed) on Kijipa (Hand woven cotton cloth using hand spun threads on a Women’s vertical loom). The textiles make use of the “Eleso/fruits” and “Osupa/moon” patterns. Textiles such as these were made as far back as the 11th century.

Below are some example of Chief Nike Okundaye’s extensive Raffia Textile collection.

A minimalist example of Malian Bogolanfini “Mudcloth”

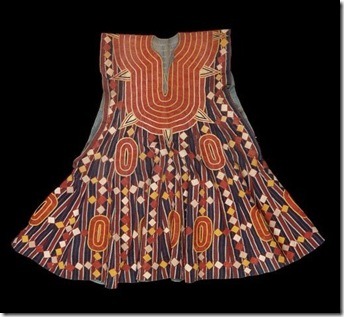

A more contemporary handwoven Dashiki made using handwoven AsoOke “stripwoven” Fabric and machine embroidery. The basic style in format though is quite old.

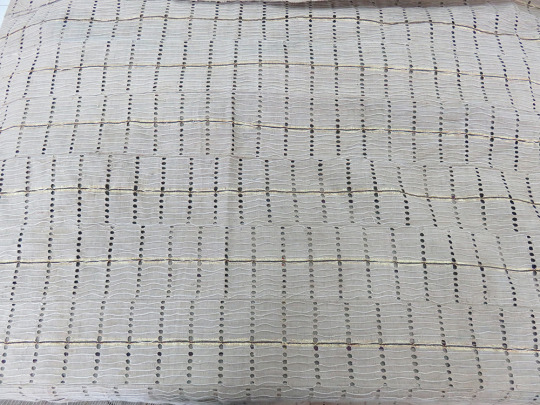

A unique cloth that incorporates machine woven Damask fabric with hand woven AsoOke, utilizing “Jawu/openwork” and metallic threads.

Being immersed in this tradition made me think about the perception African textiles in the Americas. For so many Dutch, Indian or Chinese made printed textiles have become synonymous with African cloths. These wax prints although an important part of contemporary African Identity often undercut the rich local handmade textile traditions of west and central Africa. The ancestral resist dyeing and weaving traditions that link Africa with diaspora often go unnoticed in favor of the printed textiles, as do important avenues of mutual exchange and economic development of African creative markets. The “invasion” of these foreign textiles is so absolute that they have almost completely replaced the once vibrant raffia weaving tradition of central Africa, which at one time was producing tens thousands of yards of domestic and luxury textiles. These “Wax Print” textiles were originally created by the Dutch to sell in Indonesian markets were often made to specifically imitate the Batik patterns and motifs of southeast Asia. When it was discovered that these cloths sold far better in African markets they began exporting them across the continent. Although these early 20th century Africans loved these brightly colored “new "textiles, their patterns and colorways held little to no significance to the preexisting textile traditions and at least in West African indigenous weaving and resist dyeing traditions continued to flourish and evolve alongside these newer imports. For us in the Diaspora it important to understand that our ancestors would not be able to recognize brightly colored machine made textiles that we associate with Africa now. What we call a dashiki is vastly different from the ones they wore, but also very similar to those made in West Africa today by West African weavers and tailors, who maintain these vibrant traditions. The technicolor floral and kaleidoscope patterns that dominate printed textiles would have also been alien to them, but the tie and dyed patterns that are still made and used in Nigeria, Mali and Liberia would have been strikingly familiar, as they not only predate the transatlantic slave trade, but may have been practiced by the descendants of African slaves in the Americas up until the 19th century.

Below: Pre 20th century robes: Top: Kanuri robe from the mid 19th century embroidery on imported silk. Second: Mande robe from the 17th century indigo dyed robe with tie dyed “eleso” pattern. Third: mid 19th century embroidered Dahomean robe from what is now the Republic of Benin, Strip woven fabric with embroidery. Fourth: 17th century strip woven tunic most likely from a Mande speaking region.

The indigenous textile traditions of Africa are rich and varied, and represent both continuity and change. As we in the diaspora begin to explore African textiles it is important that we understand the roots of these traditions and the fascinating ways in which these aesthetics and traditions relate to our own textile and aesthetic traditions and how we can economically support this incredible work made by black artisans.

My Time in Ogidi-Ijumu came to an end yesterday. With the indigo pit finally ready I was able to dye the threads and the textiles I was preparing over the previous weeks. For so many people Nigerian (and by extension all west african) textiles bring to mind wax print ankara cloth, but for me and the other artisans at the Nike Art Center in Ogidi the ancient arts of Adire Oniko Adire Eleko, Aso-ofi and Aso-oke are at the core of the long and rich tradition of adornment. I would like to thank Mrs. Agnes Umeche for being such a patient and fantastic teacher I cant wait to share what you have taught me with students in the U.S.A!

Post link