#auguste toulmouche

The Love Letter (Detail)

Auguste Toulmouche, 1883

Said she can’t help it

“Humiliation” by The National // Dans la Bibliotheque by Auguste Toulmouche

Post link

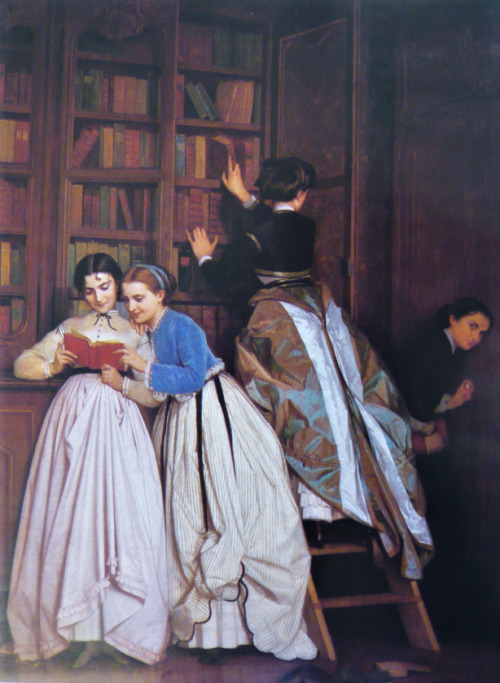

Forbidden Fruit (Le Fruit Défendu) by Auguste Toulmouche, 1865, illustrating how young women have always rebelled against having their access to knowledge policed.

Nineteenth-century French and British families kept a close eye on the literature allowed to pass into the hands of unmarried girls (married women were not automatically exempt, either). While Toulmouche’s painting garnered great acclaim for its aesthetic charms when it was exhibited at the Salon of 1865, a contemporary male art critic’s sour aside summed up the prevailing attitude to independent female minds:

“I do not approve of these silly girls; instead of searching forbidden pages for the knowledge that they lack, they would do better to leave tomorrow’s lover the pleasure of instructing them in the matters of which they are ignorant.” Paul Mantz quoted in Women Readers in French Painting 1870-1890 by Kathryn J. Brown.

No comment.

This is so interesting–what a great painting!

Also interesting: in the 18th century, pornographic books (French and English) often contained a ‘Note to Readers’ that assumed a mixed-gender readership; there was almost always an admonition to make sure your maidservants didn’t get hold of the book (wink, nudge). In Western Europe, from about late antiquity through the mid-19th century, the very general assumption was that women were naturally horny, lusty, and incapable of controlling themselves sexually: this is why they can’t be rulers or merchants or priests, because unlike men, they’re incapable of separating their minds/spirits from the base demands of their bodies. Think of Chaucer’s Wife of Bath–she’s a positive rendition of the prevailing misogynist stereotype.

Even with these general attitudes, in certain times and places women were able to receive an education and be praised for their minds: in 17th-18th century France, many intellectual and artistic salons were run by women–a sharp mind and witty conversation were part of the feminine ideal during that period. Many salonnièreswere prolific writers, particularly of fairy tales–the best-known versions of “Beauty and the Beast,” for example, come from female salon writers. (Of course, the most famous and celebrated salon writer of fairy tales was still a dude–Charles Perrault. But check out his fairy tale “Ricky of the Tuft”.)

At the end of the 18th century though, the Industrial Revolution came along. The Industrial Revolution radically changed the organization of society: most notably, the population shifted, in huge numbers, from country to city–in 1800, 80% of people lived in the country; by 1900, 80% lived in cities. The other big change was a new emphasis on the nuclear family (father, mother, children) as the primary unit of society. In a farming economy, the emphasis was more communal–you needed a ton of extended relatives and friendly neighbors to help you work the land and bring the harvest in. But urban industrial capitalism favored a smaller, more isolated family unit.

Along with the Industrial Revolution came Romanticism. As the old farming society broke down in the face of hard-headed Science, Progress, and Industry, Romanticism championed nature, emotion, and immediacy of experience, and mourned–from the cities–the destruction of the old pastoral way of life, which seemed a time of Innocence. So, the Romantics also developed the modern concept of Childhood: for the Romantics, children were the ideal citizens and Christians, because of their innocence. Earlier eras saw children as basically short, stupid adults who needed to grow up quickly to pull their weight on the farm; the Romantics argued that children were intrinsically differentandbetter than adults–their ignorance was the innocence of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden before the Fall. The Victorians took this idea and fetishized the shitout of it–in some ways, pedophilia is almost, like, a defining feature of the Victorian period.

ANYWAY, by the mid-19th century, the old gender roles had basically flipped: now WOMEN were, like children, so pureandspiritualthat they shouldn’t be subjected to the demands of nasty urban capitalism. It was MEN’S thrusting lustiness that made them suited for the labor market, politics, and the like. It was Women’s Duty to maintain the home as a haven of purity and rest from the big bad world out there. This is the ‘Angel in the House’ thing that the Victorians loved, and we still have today. Women, in this construct, are basically asexual: any sexual feelings they have are just the means by which she can get a child, upon which all of her energy is properly lavished. A Good Woman will therefore submit to her Wifely Duty, but she wasn’t expected or supposed to get any real pleasure out of it–it was only men who could enjoy so base an act. Thanks, Victorians, for normalizing non-consensual sex! And your pedophiliac fixation on innocence!

Of course, these attitudes are VERY MUCH about race and social class: all the sexuality denied to middle- and upper-class white women was dumped on women of color and working-class women. Black women were overtly de-feminized AND hypersexualized, in order to justify subjecting them to the horrors of slave labor–this is the crux of Sojourner Truth’s famous speech ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ And working-class women, who always had to work outside the home, were stuck with this as well: their ‘innocence’–socially desired ignorance of sexuality–was suspect, because they weren’t as cloistered as women of higher social classes. of course, all of this got rationalized as inherent and biological–middle/upper-class asexualized women were the “most evolved.” White upper- and middle-class men, on the other hand, could obviously be trusted, despite their base bodily desires–they had the requisite “civilized” upbringing (and bloodline) to control themselves, unlike poor men and men of color. Sound familiar?

SO: denying women access to education, in the 19th century, was rationalized on very different grounds than in previous centuries: anything that might Corrupt and Destroy her Natural Purity, Innocence, and Squeamishness was to be forbidden, and any woman who displayed curiosity about such things was Morally Suspect. The previous assumptions about women as a whole–don’t let them have access to sexy stuff, because it will inflame their already weak minds and lusty bodies, and then CHAOS–was pushed onto women of color and the working classes. Opposition to education for middle-/upper-class women, in this period, was often framed in terms of ruining her Character, turning her into an Undesirable Bad Girl, and depriving her husband of his God-Given rights to control his wife’s access to knowledge–this rhetoric often focused on individual and interpersonal psychology and relationships. Contrast this to oppositions to education for people of color and the working classes, which often focused on the societal chaos that comes from inferiors getting ideas above their station.

IN CONCLUSION: that fuckin dude’s comment on the painting is so stereotypically 19th century it makes me want to puke, and 17th century French women would have been allowed some measure of witty smackdown.

Post link

‘The Hesitant Bride’ - Auguste Toulmouche

Oil on canvas, 1866

Additional information about this piece

Post link