#austerlitz

Climbed the 81 stairs of the Pyramid of Austerlitz (NL). Built in 1804. Accordingly attired.

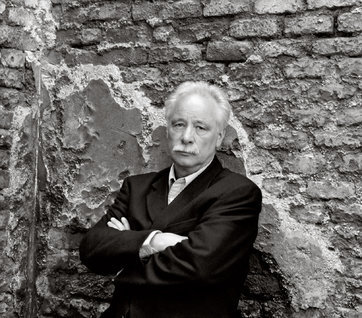

(photo by Isolde Ohlbaum)

Not sure how I missed this, but back in May, Joshua Cohen had a fantastic little review of the posthumous collection of W.G. Sebald’s early literary criticism, A Place in the Country, in the Times. Aside from being whip smart, Cohen’s piece mentions a few features about Sebald’s “novels” that I hadn’t realized:

All four of his novels bear the marks of these influences, in images and even lines lifted verbatim: parts of Stifter’s story “Der Condor” appear in “The Rings of Saturn,” and of Walser’s short story “Kleist in Thun” in “Vertigo,” unacknowledged. But then Sebald also borrowed from the living, especially from the biographies of émigrés: the poet and translator Michael Hamburger has a cameo in “The Rings of Saturn.”

None of this was plagiarism, or even allusion. This was Sebald proposing a self whose only homeland was the page: Existence beyond the bindings was too compromising. This principle corresponds to the photographs Sebald included in his novels, black-and-white portraits he’d purchased from antique markets; in “Austerlitz,” that boy in the cape holding the plumed tricorn is not Jacques Austerlitz — it can’t be: Jacques Austerlitz is fictional — and yet it is more Jacques Austerlitz than the boy it actually depicts, who remains unknown to the reader (and who remained unknown even to Sebald, who, according to James Wood, paid 30 pence for the photo).

The page is the new horizon at the same time that it’s the old one. All words and works, bound together and repeated and rephrased and reused–mine and yours and Walser’s and Sebald’s and Cohen’s–forever and ever. Of course, Sebald and Cohen say it better than any of us can.

-Hal-