#cardiovascular disease

BPA exposure during pregnancy causes oxidative stress in child, mother

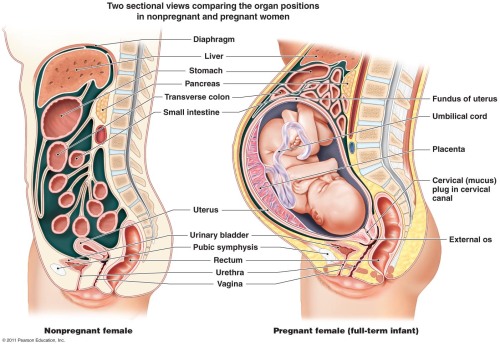

Exposure to the endocrine-disrupting chemical bisphenol A (BPA) during pregnancy can cause oxidative damage that may put the baby at risk of developing diabetes or heart disease later in life, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society’s journal Endocrinology.

Bisphenol A is a chemical used to manufacture plastics and epoxy resins. BPA is found in a variety of consumer products, including plastic bottles, food cans and cash register receipts.

Research has shown BPA is an endocrine disruptor – a chemical that mimics, blocks or interferes with the body’s hormones. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have estimated that more than 96 percent of Americans have BPA in their bodies.

Oxidative stress occurs when the body is exposed to high levels of free radicals – highly reactive chemicals that have the potential to harm cells when the body processes oxygen – and the body cannot neutralize the chemicals quickly enough to correct the imbalance. Some environmental toxins such as cigarette smoke, ionizing radiation or some metals may contain large amounts of free radicals or encourage the body to produce more of them, according to the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

“This study provides the first evidence that BPA exposure during pregnancy can induce a specific type of oxidative stress known as nitrosative stress in both the mother and offspring,” said the senior author, Vasantha Padmanabhan, MS, PhD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, MI. “Oxidative stress is associated with insulin resistance and inflammation, which are risk factors for diabetes and other metabolic disorders as well as cardiovascular disease.”

Almudena Veiga-Lopez, Subramaniam Pennathur, Kurunthachalam Kannan, Heather B. Patisaul, Dana C. Dolinoy, Lixia Zeng, Vasantha Padmanabhan. Impact of Gestational Bisphenol A on Oxidative Stress and Free Fatty Acids: Human Association and Interspecies Animal Testing Studies.Endocrinology, 2015; en.2014-1863 DOI: 10.1210/en.2014-1863

Post link

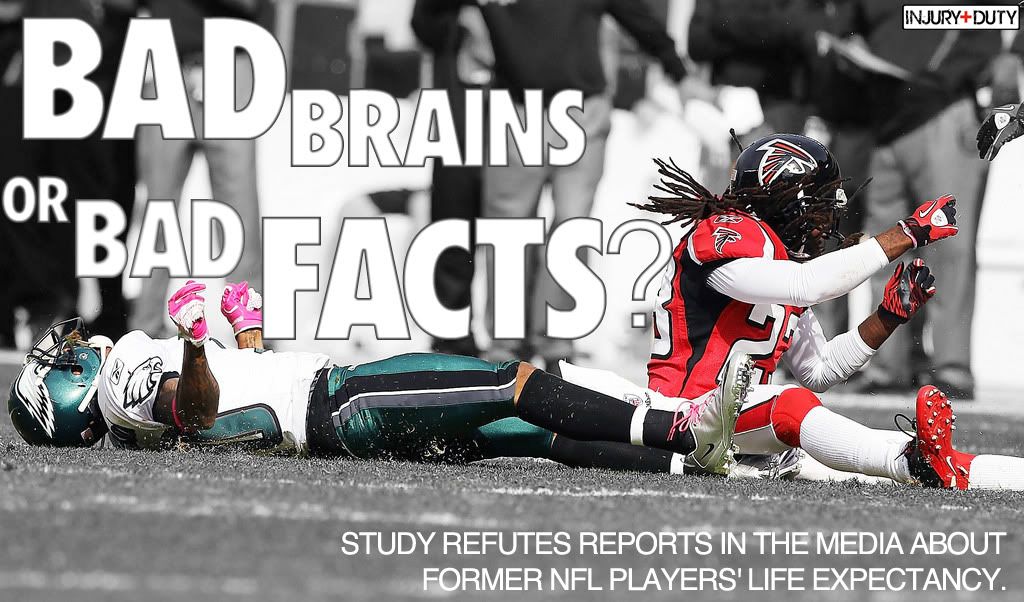

Talk of concussions in the NFL has been all the rage in last couple of years, and rightfully so. There is a lot that science is learning about the long term effects of repetitive head injuries on someones long term health, both physical and mental, but there is still a lot we don’t know or understand. However, that lack of scientific insight hasn’t stopped people from taking strong stances on the issue. The most common “knee-jerk” reaction are comments like “Come on, man! What is there to study? All that banging heads together, of course it’s not good for you! Of course it’s gonna mess guys up in the head.”

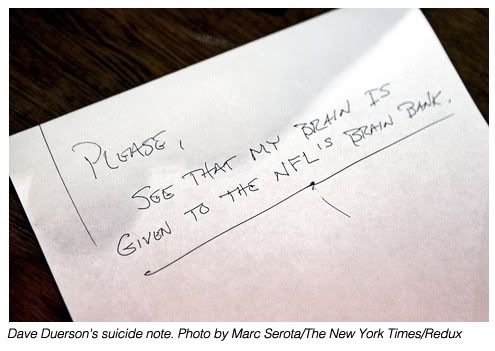

The most recent link between Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI) and off the field mental health has been the issue of suicide amongst former NFL athletes. In just over the past year-and-a-half, four former NFL players (Ray Easterling,Dave Duerson,Junior SeauandO.J. Murdock) have committed suicide, adding more fuel to the already heated debate over the long term effects of brain injuries and the game of football. One recent headline even read “Junior Seau and the disturbing NFL suicide trend”. Scary stuff, but “trend”? Is there even any hard evidence to back up these sorts of claims?

The NFL has taken a lot flack for what many consider their “nonchalant” response to the concerns surrounding mTBI and their game, so much so that the United States Congress got involved and have grilled NFL officials and doctors on the matter. Specifically, Dr. Ira Casson the former NFL doctor, told Congress that there was no proven link between football head injuries and brain disorders. Evidence since that statement has all suggested otherwise. But, the idea of “brain disorders” is a pretty broad one. In there are included everything from Alzheimer’s disease to dementia and Parkinson’s and even depression. Teasing these out and searching for an indisputable link between each disease and mTBI will take some time, mainly because the only way to truly see, on a microscopic level, what is going on in the brains of the men in question is to examine their brain tissuesafterthey have passed away.

Here’s Where It Gets Interesting: A recent study done by a group of researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) looked at the mortality (a measure of the number of deaths) among 3,439 retired football players who had played at least five years in the NFL between 1959 and 1988. Their report appeared in Volume 109, Issue 6 of the American Journal of Cardiology and what they found, well, may surprise you.

“Overall,” the study concluded, “retired NFL players from the 1959 through the 1988 seasons showed decreased all-cause and (cardiovascular disease) mortalities compared to a referent United States population of men.”

In other words NFL players, in general, live longer. Wrap your head around that for a second. If you’re anything like most people, you’re probably asking yourself “How is that possible? You mean to tell me these guys lived longer lives than guys in the general population?” Yes. That is exactly what this study found.

Researchers point out that these players for the most part lived “healthier” lives. For example, they are less likely to smoke and were in good overall health- all of which would contribute to their lower than expected likelihood of dying compared to the general United States population.

Even more interesting were the results when it came to deaths due to suicide. Researchers found that 9 former players died through suicide. Based on the numbers seen in the general population in men of the same race, age etc., the number was expected to be closer to 22. In short, the actual percentage of deaths due to suicide was 59% less than what they expected to find.

Now, although the NIOSH study indicated that NFL alumni are less likely to commit suicide than others, this shouldn’t be interpreted as “the NFL is off the hook”. This same study found that 12 of 3,439 players died of “diseases of the nervous system and sense organs”. Only 9.7 men in the general population would have died of these causes. So, there’s still work to be done and the NIOSH plans on a more complete study examining this small group of former NFL players.

This study likely raises more questions than answers, but it’s a step in the right direction. One thing is clear however, these issues aren’t going to be solved with a few changes in the rules on the field or a better built helmet. The best thing we, as both physicians and consumers of the game, can do is ask questions and demand answers. It’s going to take time, but slow motion is better than no motion.

Researchers look at the use of intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of Kawasaki disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, a rare reaction to SARS-CoV-2

Kawasaki disease (KD) is rare, with fewer than 6,000 diagnosed cases per year in the United States. It is most common in infants and young children and causes inflammation in the walls of some blood vessels in the body. KD is a common cause of acquired heart disease in children around the world, causing coronary artery aneurysms in a quarter of untreated children.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is also rare, a life-threatening illness that follows exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). MIS-C is characterized by the acute onset of fever and variable symptoms, including rash, cardiovascular complications, shock and gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting.

KD and MIS-C share several clinical features and immune responses. Both conditions are treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), a therapeutic containing antibodies purified from blood products. Antibodies in the blood protect us from a number of viral, bacterial and fungal pathogens, but when administered as IVIG, can also suppress excessive inflammation. How it does this is an ongoing area of research worldwide.

In a pair of new studies, published online October 26 and August 31, 2021, two collaborating teams of researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine examined the use of IVIG in two groups; one group used a second dose of IVIG in children with KD who do not respond to the first dose of the drug, and the other group used IVIG as an effective treatment for MIS-C.

“Our research teams looked further into KD to improve treatment, and then used what we know about that disease to advance science in another illness,” said senior author Jane C. Burns, MD, professor and director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego.