#academic medicine

The Life of an Academic Attending

Work Bestie: what’s your schedule look like today?

Me: precepting in clinic all day

Friend: ah, decubitus day.

Neuroimaging study reveals potential brain mechanism underlying chronic neuropathic pain in individuals with HIV

As medical advances help individuals with HIV survive longer, there is an increasing need to treat their chronic symptoms. One of the most common is neuropathic pain, or pain caused by damage to the nervous system.

Distal sensory polyneuropathy (DSP) is the most prevalent neurological problem in HIV infection, affecting 50 percent of all HIV patients. Most persons with DSP describe sensations of numbness, tingling, burning and stinging in their hands or feet, which impair daily functioning and can lead to unemployment and depression.

Previous research on DSP has mostly focused on the peripheral nervous system, but nerve injury cannot fully explain the wide variability in DSP symptoms. Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and University of California San Francisco instead looked at the brain to see how it may be contributing to patients’ pain.

In a new study, published online October 29, 2021 in Brain Communications, the team observed unique patterns of brain activity in HIV-DSP patients when they experienced a painful stimulus. Compared to other patients with HIV, those with DSP showed increased activity in the anterior insula, a brain area involved in predicting and emotionally processing pain.

“The anterior insula is trying to predict the future for you,” said senior author Alan Simmons, PhD, professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine and research scientist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System. “It’s forming expectations about what is about to happen to you and how you’re going to feel. These expectations of pain play an important role in determining how much pain you then actually experience.”

Pictured: HIV patients with and without chronic neuropathic pain received short or long heat stimuli on their hands (control site) or feet (neuropathic site).

“Not So Great Expectations: Pain in HIV Related to Brain’s Expectations of Relief”

Genetic Signals Linked to Problematic Opioid Use

UC San Diego School of Medicine researchers asked more than 132,000 23andMe research participants of European ancestry “Have you ever in your life used prescription painkillers, such as Vicodin and Oxycontin, not as prescribed?” More than 21 percent said yes. Then, in a genome-wide association study, the team discovered novel genomic regions that influenced using opiate drugs not as prescribed. They also identified strong genetic correlations with other substance use traits, including opioid use disorder.

The study, published November 2, 2021 in Molecular Psychiatry, was led by Sandra Sanchez Roige, PhD, and Abraham Palmer, PhD.

Post link

Does High Stress in a Home Cause Childhood Obesity?

In a recent study, published in Clinical Obesity, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found associations between adverse home environments and appetite hormones in children.

Researchers measured high stress factors (maternal depressive symptoms, family stress and socioeconomic disadvantage) in the households of 593 Chilean children at ages 10 and 16. At age 16, the participants provided fasting blood samples for assessment of adipokines and appetite hormones.

The study found high levels of stress during childhood and adolescence can reduce levels of adiponectin, the body’s fat burning hormone, which makes it difficult to lose weight and contributes to obesity.

Patricia East, PhD, senior author of the study in the Department of Pediatrics at UC San Diego, explains more and how the results from participants from Chile can be used for patients in the United States.

Question: What is the clinical significance of this study?

Answer: Our results show that not only are high levels of stress during childhood and adolescence contributing to the reduction in the body’s fat burning hormone, which makes it difficult to lose weight, but because fat-burning hormones reduce inflammation and help regulate the body’s glucose levels, lower levels of this hormone, adiponectin, may also be an early red flag for developing type 2 diabetes.

It may be advisable for physicians to screen for diabetes in children and teens who are exposed to high levels of stress and have a lot of abdominal fat (a waist circumference above the 90th percentile or approximately greater than 70 centimeters).

Like the United States, Chile is a developed, upper-middle income nation with a highly literate population and good access to health care. Prevalence of overweight/obesity is similar between the U.S. and Chile, at approximately 40 and 30 percent, respectively.

A recent National Chilean Health Survey found high but equivalent prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking, high cholesterol and hypertension, between Chile and the U.S. Thus, while cultural factors, such as diet and physical activity, likely play a role in risk for diabetes, disease prevalence and contributing risk factors are similar between the two countries.

Q: What types of health issues do children with obesity face?

A: Rates of pediatric type 2 diabetes are rapidly increasing and are occurring at younger ages. Risk factors for children and teens include being overweight, inactivity and having a family history of diabetes.

Many children develop type 2 diabetes in their early teens. Adolescent girls are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than are adolescent boys.

Q: What are next steps now that you have results?

A: We are currently examining the associations between childhood adversity, appetite hormones and glucose and insulin levels at age 23 to determine if in fact early adversity and fat burning hormones link to type 2 diabetes in young adulthood.

— Michelle Brubaker

Post link

[The] UC San Diego-led team will receive a $9 million grant from the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) initiative to help advance this research and position it for the next phases of drug development. ASAP is a coordinated research initiative to advance targeted basic research for Parkinson’s disease. Its mission is to accelerate the pace of discovery and inform the path to a cure through collaboration, research-enabling resources and data-sharing. The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research is the implementation partner for ASAP and issuer of the grant, which contributes to the Campaign for UC San Diego.

“This grant is supporting some of the most incredible progress being made in the Parkinson’s sphere. It’s a game-changing strategy that we hope will improve how Parkinson’s is treated,” said David Brenner, MD, vice chancellor of Health Sciences. “We are grateful to ASAP for making these advancements possible.”

Discovery of new metabolic pathway for stored sugars helps explain how cellular energy is produced and expended in obesity, advancing therapeutic potential

Humans carry around with them, often abundantly so, at least two kinds of fat tissue: white and brown. White fat cells are essentially inert containers for energy stored in the form of a single large, oily droplet. Brown fat cells are more complex, containing multiple, smaller droplets intermixed with dark-colored mitochondria — cellular organelles that give them their color and are the “engines” that convert the lipid droplets into heat and energy.

Some people also have “beige” fat cells, brown-like cells residing within white fat that can be activated to burn energy.

In recent years, there has been much effort to find ways to increase brown or beige fat cell activity, to induce fat cells, known as adipocytes, to burn energy and generate heat in a process called thermogenesis as a means to treat obesity, type 2 diabetes and other conditions.

But the therapeutic potential of brown fat — and perhaps beige fat cells —has been stymied by the complexity of the processes involved. It wasn’t until 2009 that the existence of active brown fat cells in healthy adults was confirmed; previously it was believed they were common only in newborns.

In a new study, published online October 27, 2021 in Nature, an international team of researchers led by senior author Alan Saltiel, PhD, director of the Institute for Diabetes and Metabolic Health at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, describe how energy expenditure and heat production are regulated in obesity through a previously unknown cellular pathway.

Image: Artistic rendering of a brown fat cell with nucleus in pink, mitochondria in purple and yellow lipid droplets scattered throughout. Image courtesy of Scientific Animations.

“Sweet! How Glycogen is Linked to Heat Generation in Fat Cells”

Researchers look at the use of intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of Kawasaki disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, a rare reaction to SARS-CoV-2

Kawasaki disease (KD) is rare, with fewer than 6,000 diagnosed cases per year in the United States. It is most common in infants and young children and causes inflammation in the walls of some blood vessels in the body. KD is a common cause of acquired heart disease in children around the world, causing coronary artery aneurysms in a quarter of untreated children.

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is also rare, a life-threatening illness that follows exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). MIS-C is characterized by the acute onset of fever and variable symptoms, including rash, cardiovascular complications, shock and gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting.

KD and MIS-C share several clinical features and immune responses. Both conditions are treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), a therapeutic containing antibodies purified from blood products. Antibodies in the blood protect us from a number of viral, bacterial and fungal pathogens, but when administered as IVIG, can also suppress excessive inflammation. How it does this is an ongoing area of research worldwide.

In a pair of new studies, published online October 26 and August 31, 2021, two collaborating teams of researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine examined the use of IVIG in two groups; one group used a second dose of IVIG in children with KD who do not respond to the first dose of the drug, and the other group used IVIG as an effective treatment for MIS-C.

“Our research teams looked further into KD to improve treatment, and then used what we know about that disease to advance science in another illness,” said senior author Jane C. Burns, MD, professor and director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego.

“Same Treatment Tested for Kids with Kawasaki Disease and Rare COVID-19 Reaction”

A stained histological slide, magnified 100 times, depicts cancer cells expansively spread through normal breast tissues, including a duct completely filled with tumor cells. Credit: Dr. Cecil Fox, National Cancer Institute

Researchers describe how malignancies leverage evolution and basic cellular functions to promote immune dysfunction and a better future for themselves

Writing in EMBO reports, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center at UC San Diego Health describe how a pair of fundamental genetic and cellular processes are exploited by cancer cells to promote tumor survival and growth.

Cancer is driven by multiple types of genetic alterations, including DNA mutations and copy number alterations ranging in scale from small insertions and deletions to whole genome duplication events.

Collectively, somatic copy number alterations in tumors frequently result in an abnormal number of chromosomes, termed aneuploidy, which has been shown to promote tumor development by increasing genetic diversity, instability and evolution. Approximately 90 percent of solid tumors and half of blood cancers present some form of aneuploidy, which is associated with tumor progression and poor prognoses.

In recent years, it has become apparent that cells cohabiting within a tumor microenvironment are subject not only to external stressors (mainly of metabolic origin, such as lack of nutrients), but also to the internal stressor aneuploidy. Both activate a stress response mechanism called the unfolded protein response (UPR), which leads to an accumulation of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of cells — an organelle that synthesizes proteins and transports them outside the cell.

When this primary transport/export system is disrupted, UPR attempts to restore normal function by halting the accumulation of misfolded proteins, degrading and removing them and activating signaling pathways to promote proper protein folding.

If homeostasis or equilibrium is not re-established quickly, non-tumor cells undergo cell death. Conversely, cancer cells thrive in this chaos, establishing a higher tolerance threshold that favors their survival.

“In these circumstances, they also co-opt neighboring cells in a spiral of deceit that progressively impairs local immune cells,” said co-senior author Maurizio Zanetti, MD, professor of medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine and a tumor immunologist at Moores Cancer Center with Hannah Carter, PhD, associate professor of medicine and a computational biologist. Zanetti had previously introduced the hypothesis in a Sciencecommentary.

The researchers hypothesized that aneuploidy, UPR and immune cell dysregulation could be linked together in a deadly triangle. In the new study, Zanetti, Carter and colleagues analyzed 9,375 human tumor samples and found that cancer cell aneuploidy intersects preferentially with certain branches of the signaling response to stress and that this finding correlates with the damaging effects of aneuploidy on T lymphocytes, a type of immune cell.

“This was an ambitious goal not attempted before,” said Zanetti. “It was like interrogating three chief systems together — chromosomal abnormalities in toto, signaling mechanisms in response to endogenous stress and dysregulation of neighboring immune cells — just to prove a bold hypothesis.

“We knew the task would be challenging,” added Carter, “and that we would need to create and refine new analytical tools to test our hypotheses in heterogeneous human tumor data, but it was a worthwhile risk to take.”

The findings, they said, show that the stress response in cancer cells serves as an unpredicted link between aneuploidy and immune cells to “diminish immune competence and anti-tumor effects.” It also demonstrates that molecules released by aneuploid cells affect another type of immune cells — macrophages — by subverting their normal function to turn them into tumor-promoting actors.

“Tumor Reasons Why Cancers Thrive in Chromosomal Chaos”

A new trial by UC San Diego Health infectious disease specialist Maile Young Karris, MD, will use longitudinal questionnaires and qualitative interviews to assess the impact of living in an interconnected virtual village on the loneliness known to afflict older people with HIV.

“It’s about changing the culture back to how it used to be,” Karris said, “where neighbors actually knew each other and helped each other and you didn’t have to worry so much about your poor dad who lives by himself, far away from you, because you knew that his neighbors would call you if anything happened or would make sure that he was eating.”

Hepatitis A Vaccination Required for Herd Immunity in People Experiencing Homelessness or Who Use Drugs

In the U.S., hepatitis A outbreaks are repeatedly affecting people experiencing homelessness or who use drugs. A 2017-19 Kentucky outbreak primarily among these groups resulted in 501 cases, six deaths. Vaccination efforts likely averted 30 hospitalizations and $490K in costs, but UC San Diego and Oxford researchers say more could have been saved if initiated earlier and faster. They determined herd immunity in these populations requires 77 percent vaccinated, underscoring need for outreach.

The study, published October 18, 2021 in Vaccine, was led by Natasha Martin, DPhil, professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and Emmanuelle Dankwa and Christl Donnelly, CBE FMedSci FRS, at University of Oxford.

Pictured: A UC San Diego Health employee is vaccinated against hepatitis A during an outbreak in San Diego, Calif. in 2017. Credit: Erik Jepson/UC San Diego Publications

— Heather Buschman, PhD

Post link

Electroconvulsive therapy has long been used to treat severe, persistent depression, but not without unwelcome side effects; researchers looked at whether magnets might be better over the long-term

Treatment-resistant depression or TRD is exactly what it sounds like: a form of mental illness that defies effective therapy. It is not rare, with an estimated 3 million persons in the United States suffering from TRD.

In a novel study, published in the October 19, 2021 online issue of The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, an international team of scientists led by senior author Zafiris J. Daskalakis, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at University of San Diego School of Medicine, investigated whether continued magnetic seizure therapy (MST) might effectively prevent the relapse of TRD, particularly in comparison to what is known about electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), the current standard of care but a method with mixed results and a controversial history.

ECT often works when other treatments are unsuccessful, but it does not work for everyone, and some side effects may still occur, such as confusion and memory loss. These concerns, and a lingering public stigma, have limited its widespread use.

MST is a different form of electrical brain stimulation, debuting in the late-1990s. It induces a seizure in the brain by delivering high intensity magnetic field impulses through a magnetic coil. Stimulation can be tightly focused to a region of the brain, with minimal effect on surrounding tissues and fewer cognitive side effects. Like ECT, MST is being studied for treating depression, psychosis and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Free Period: Our OB/GYN Expert Weighs in On New Law for California Schools

Period products will be provided free of charge in public schools across California starting next school year as part of new legislation recently signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom.

The Menstrual Equity for All Act will require public schools with students in grades six to 12, community colleges and the California State University System to provide the free products in the 2022-2023 academic year.

We asked Alice Sutton, MD, obstetrician/gynecologist at UC San Diego Health, to explain the importance of providing free period products to this population of young women and how a comprehensive approach to women’s health is critical, especially for underserved students.

Question: What are some benefits to having tampons freely available in schools?

Answer: Students experiencing a lack of access to menstrual products, education, hygiene facilities, waste management or a combination of these, may skip school if they don’t have adequate sanitary products, or they may improvise with items, such as paper towels that are not meant for menstrual hygiene.

Period poverty causes physical, mental and emotional challenges. Having menstrual products available in school will help students concentrate on their studies and keep them in class while meeting their health care needs.

Q: Are there concerns about whether there’s enough support in schools to help young women who are menstruating?

A: Young women who are experiencing painful or heavy periods often don’t know that there are safe and effective treatments for these issues. Sometimes the discomfort is bad enough that they miss class or extracurricular activities.

Having a nurse, teacher, coach or other trusted adult in a young women’s life in the school setting provides support and could steer her towards making an appointment with an OB/GYN to discuss options for management, such as lifestyle interventions and medications.

Q: Besides providing tampons, what else should schools be doing to support reproductive health in young people?

A: Appropriate education about the menstrual cycle, tailored to their age-level should be provided. At an even more basic level, some students may not come from homes where they have a parent who they can ask for advice, and so school may be the place where they can find a trusted adult who provides them with accurate information and can point them to appropriate resources.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a first reproductive health visit between the ages of 13 and 15. It is a good time to establish care and have a first visit where the adolescent has the opportunity to discuss concerns privately with a doctor. Gynecology visits at this age are tailored to the patient. Topics that might be covered include normal anatomy and normal menstruation, healthy relationships and consent, immunizations, physical activity, substance use including alcohol and tobacco, eating disorders, mental health, sexuality, contraception and pregnancy prevention and sexually transmitted infections.

— Michelle Brubaker

Post link

An international team researchers, including University of California San Diego School of Medicine, has broadened and deepened understanding of how inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) affect different populations of people and, in the process, have identified new gene variants that may cause the diseases.

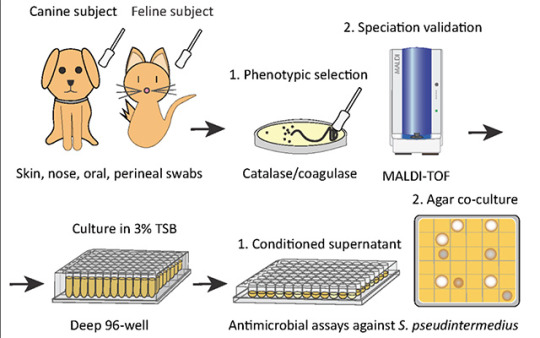

Researchers identify a bacteria on healthy cats that produces antibiotics against severe skin infections; the findings may lead to new bacteriotherapies for humans and their pets

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine used bacteria found on healthy cats to successfully treat a skin infection on mice. These bacteria may serve as the basis for new therapeutics against severe skin infections in humans, dogs and cats.

The study, published in eLife on October 19, 2021, was led by Richard L. Gallo, MD, PhD, Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Dermatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, whose team specializes in using bacteria and their products to treat illnesses — an approach known as “bacteriotherapy.”

Skin is colonized by hundreds of bacterial species that play important roles in skin health, immunity and fighting infection. All species need to maintain a diverse balance of healthy skin bacteria to fight potential pathogens.

“Our health absolutely depends on these ‘good’ bacteria,” said Gallo. “They rely on our healthy skin to live, and in return some of them protect us from ‘bad’ bacteria. But if we get sick, ‘bad’ bacteria can take advantage of our weakened defenses and cause infection.”

This is the case with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP), a bacterium commonly found on domesticated animals that becomes infectious when the animals are sick or injured. MRSP is an emerging pathogen that can jump between species and cause severe atopic dermatitis, or eczema. These infections are common in dogs and cats, and can also occur in humans, though rates of human infection vary around the world. As its name suggests, MRSP is resistant to common antibiotics and has been difficult to treat in clinical and veterinary settings.

To address this, researchers first screened a library of bacteria that normally live on dogs and cats and grew them in the presence of MRSP. From this, they identified a strain of cat bacteria called Staphylococcus felis(S. felis) that was especially good at inhibiting MRSP growth. They found that this special strain of S. felis naturally produces multiple antibiotics that kill MRSP by disrupting its cell wall and increasing the production of toxic free radicals.

“The potency of this species is extreme,” said Gallo. “It is strongly capable of killing pathogens, in part because it attacks them from many sides — a strategy known as ‘polypharmacy.’ This makes it particularly attractive as a therapeutic.”

Bacteria can easily develop resistance to a single antibiotic. To get around this, S. felis has four genes that code for four distinct antimicrobial peptides. Each of these antibiotics is capable of killing MRSP on their own, but by working together, they make it more difficult for the bacteria to fight back.

Having established how S. felis kills the MRSP, the next step was to see whether it could work as a therapy on a live animal. The team exposed mice to the most common form of the pathogen and then added either S. felis bacteria or bacterial extract to the same site. The skin showed a reduction in scaling and redness after either treatment, compared with animals that had no treatment. There were also fewer viable MRSP bacteria left on the skin after treatment with S. felis.

Next steps include plans for a clinical trial to confirm whether S. felis can be used to treat MRSP infections in dogs. Bacteriotherapies like this one can be delivered via topical sprays, creams or gels that contain either live bacteria or purified extract of the antimicrobial peptides.

Pictured above: To identify candidates for a new bacteriotherapy against skin infection, researchers first screened various bacteria from dogs and cats and co-cultured them with S. pseudintermedius in liquid and agar antimicrobial assays.

“Cat Bacteria Treats Mouse Skin Infection, May Help You and Your Pets As Well”

Left: JoAnn Trejo, PhD, is professor in the Department of Pharmacology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and assistant vice chancellor for UC San Diego Health Sciences Faculty Affairs. Right: Elizabeth Winzeler, PhD, is professor in the Division of Host Microbe Systems and Therapeutics in the Department of Pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and adjunct professor in the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at UC San Diego.

Leaders in cell biology and anti-malarial drug development respectively, JoAnn Trejo and Elizabeth Winzeler were recognized by their peers with one of the highest honors in health and medicine.

Trejo is known for discovering how cellular responses are regulated by molecules known as G protein-coupled receptors, particularly in the context of vascular inflammation and cancer. Her findings have advanced the fundamental knowledge of cell biology and helped identify new targets for drug development. Trejo’s research has been continuously funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including a recent NIH R35 Outstanding Investigator Award.

Winzeler is known for her early contribution to the field of functional genomics, where she worked primarily in the model yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Concerned about global health disparities and the alarming rise in the number of worldwide malaria cases in the early 2000s, she shifted her research focus to malaria, beginning with functional genomics and then moving to drug discovery.

“Two UC San Diego Scientists Elected to National Academy of Medicine”

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has awarded researchers at University of California San Diego approximately $30 million over five years to expand and deepen longitudinal studies of the developing brain in children.

“This is a groundbreaking study of normal and atypical brain developmental trajectories from day 0 to 10 years of age in a large sample of about 8,000 families,” Christina Chambers, PhD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and professor in the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science at UC San Diego.

Molecular profiling is more often used after standard cancer treatments have failed, but a new study suggests that it could effectively guide first-line treatment, especially for poor-prognosis cancers

In treating cancer, personalized medicine means recognizing that the same disease can behave differently from one patient to another, and precision medicine means that diagnosis and treatment should involve understanding the specific genetic makeup of each patient’s tumor and disease.

In a recent study, published October 4, 2021 in Genome Medicine, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center at UC San Diego Health, with colleagues elsewhere, report that conducting genomic evaluations of advanced malignancies can be effective in guiding first-line-of-treatment, rather than waiting until standard-of-care therapies have failed.

By their nature, cancers are molecularly complex, each with a heterogeneous combination of genetic mutations that, more often than not, defy easy treatment. With every stage and line of therapy, tumor cells adapt to become more resistant to remedy.

The study authors hypothesized that developing matched, individualized combination therapies for patients with advanced cancers who had not been previously treated might be feasible and effective.

Just under 150 adults with newly diagnosed cases of advance malignancies were enrolled in the prospective study at two sites: Moores Cancer Center and Avera Cancer Institute in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. The patients had either incurable, lethal cancers (at least a 50 percent cancer-associated mortality rate within two years) or they had a rare tumor with no approved therapies.

Researchers performed extensive genomic profiling of all patients, identifying and documenting all detectable gene mutations to create a molecular profile of each patient’s tumor that would guide their precision cancer therapy.

“Each patient received a personalized N-of-1 treatment plan that optimally matched therapeutic agents to their tumor’s distinct biology, while also taking into account other variables, such as underlying conditions or co-morbidities unique to that patient,” said first author Jason Sicklick, MD, professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine and surgical oncologist at Moores Cancer Center.

Pictured: Cancer cells ( Thomas Deerinck)

“At Initial Cancer Diagnosis, a Deeply Personalized Assessment”

Fatigue Associated With Worse Cognitive Functioning in Older Persons with HIV

Older people with HIV experience a type of fatigue associated with worse cognitive and everyday functioning, according to a paper published in the journal AIDS by UC San Diego School of Medicine researchers. That association remains even after accounting for factors like depression, anxiety and sleep quality.

The finding suggests fatigue is important symptom to assess and consider in the context of aging with HIV, which is a major focus in HIV research. By 2030, it’s estimated that 73 percent of persons with HIV will be age 50 or older.

“There’s a dearth of research examining the fatigue-cognition relationship — in particular in people with HIV,” said senior author Raeanne Moore, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

“This is one of the first studies to examine it.”Moore and her team, led by graduate student researcher Laura Campbell, studied 105 people ages 50 to 74 — 69 persons with HIV and 36 persons without HIV — recruited from ongoing studies at UC San Diego’s HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center and from the community. Participants completed neuropsychological testing, a performance-based measure of everyday functioning and self-report questionnaires about fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep quality, and everyday functioning.

Fatigue was the only factor associated with cognition among participants with HIV.

“The fact that we found this very strong relationship between fatigue and objective cognition among persons with HIV may speak to the biological underpinnings of fatigue and how that might be related to cognition, given that we also see this relationship in other chronic disease populations as well,” Moore said.

“Down the road, the hope is that we can identify and modify some of some of these biological mechanisms with treatment.“Fatigue is often one of the primary complaints that patients present with, so identifying new ways to reduce fatigue could have a significant impact on daily cognitive abilities and overall quality of life.”

— Corey Levitan

Pictured above: A colorized scanning electron micrograph of an HIV-infected human T cell. Image courtesy of NIH.

Post link

Pharmacists at Higher Risk of Suicide than General Population

The pandemic put a spotlight on burnout and suicide among physicians and nurses, but until now, less was known about the mental health of pharmacists.

In the first study to report pharmacist suicide rates in the United States, a team of researchers led by Kelly C. Lee, PharmD, professor of clinical pharmacy at UC San Diego Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, found that suicide rates are higher among pharmacists compared to non-pharmacists, at an approximate rate of 20 per 100,000 pharmacists compared to 12 per 100,000 in the general population. Results of the longitudinal study were published May 13, 2022 in Journal of the American Pharmacists Association.

The most common means of suicide in this population was firearms, followed by poisoning and suffocation. The prevalence of firearm usage was similar between pharmacists and the general population, but poisoning via benzodiazepines, antidepressants and opioids was more frequent among pharmacists.

The data also provide some insight into contributing factors, including a history of mental illness and a high prevalence of job problems. Job problems are the most common feature of suicides across health care professions.

For pharmacists, Lee said job problems reflect significant changes in the industry in recent years, with more pharmacists employed by hospitals and chain retailers than small, private pharmacies more common in the past. The responsibilities of a pharmacist have also grown considerably, with larger volumes of pharmaceuticals to dispense and increasing demands to administer vaccines and other health care services.

“Pharmacists have many more responsibilities now, but are expected to do them with the same resources and compensation they had 20 years ago,” said Lee. “And with strict monitoring from state and federal regulatory boards, pharmacists are expected to perform in a fast-paced environment with perfect accuracy. It’s difficult for any human to keep up with that pressure.”

Future research will further evaluate which job problems have the biggest impact and how the field can better respond. In the meantime, Lee advised pharmacists to encourage help-seeking behaviors amongst themselves and their colleagues.

“Mental health is still highly stigmatized, and often even more so among health professionals,” said Lee. “Even though we should know better, there is such an expectation to appear strong, capable and reliable in our roles that we struggle to admit any vulnerabilities. It’s time to take a look at what our jobs are doing to us and how we can better support each other, or we are going to lose our best pharmacists.”

— Nicole Mlynaryk

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (En Español: 1-888-628-9454; Deaf and Hard of Hearing: 1-800-799-4889) or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

Post link

Tome Sweet Tome

The surfaces of all cells in nature are festooned with a complex and diverse array of sugar chains (called glycans). These perform a wide variety of biological functions, from the proper folding of proteins to cell-to-cell interactions. Their ubiquity in nature underscores their essentialness to complex life.

This week, the fourth edition of “Essentials of Glycobiology” (the study of glycans) was published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. It’s a continuation and updating of landmark work by a consortium of editors, led by Ajit Varki, MD, Distinguished Professor in the departments of Medicine and Cellular and Molecular Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine, with contributions from a number of UC San Diego scientists and physicians, including Jeffrey D. Esko, PhD, Distinguished Professor of cellular and molecular medicine; Pascal Gagneux, PhD, professor of pathology and anthropology, and Kamil Godula, PhD, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, and Amanda Lewis PhD, professor of obstetrics-gynecology and reproductive science.

Varki and Esko are also founding directors of the Glycobiology Research and Training Center (GRTC) at UC San Diego, established in 1999, and have recently handed over leadership to Lewis and Godula.

Glycobiology is a relatively new scientific discipline. The term was only coined in 1988, recognizing the combining of carbohydrate chemistry and biochemistry to focus on glycans, which have since proven to have a multitude of diverse and often critical roles in biology.

They have been linked to human origins and as a key evolutionary marker. They are found to both inhibit and promote tumor growth; and the presence of a particular sialic acid in red meat may be linked to increased cancer risk in humans. Another class of glycans called glycosaminoglycans have been shown by Esko and colleagues to be involved in COVID-19 coronavirus pathogenesis. The cover of the fourth edition presents an all-atom model of infamous spike protein of the pandemic virus, emphasizing the massive array of glycan chains modelled by UC San Diego professor of biology Rommie Amaro.

Varki, Esko and colleagues at the GRTC have been central to many of the advances in glycobiology, and the textbook, which originally debuted in 1999, has been an enduring effort to broadly introduce and describe the rapidly changing discipline.

For example, the second edition of “Essentials of Glycobiology,” published in 2008, appeared simultaneously in print from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, and free online to reach a wider audience. Subsequent editions have also been free online at the National Center for Biotechnology Information at the National Library of Medicine.

“This approach ensures that everyone, from the layperson to the high school student to the graduate student in a developing country, has free access to the knowledge the book contains, while increasing awareness of the availability of a printed edition that may be more suitable for some readers’ requirements,” said Varki at the time.

— Scott LaFee

Pictured above: In this electron micrograph, the surface of a bacterium is fuzzy with a coating of glycans.

Post link

In recent years, hallucinogens ranging from LSD and ecstasy (MDMA/Molly) to salvia divinorum and ketamine have garnered renewed interest as potential as therapeutics for a variety of psychiatric conditions. Both LSD and ketamine, for example, are being widely studied as a treatment for major depression.

In a study published online April 28, 2022 in the journal Addictive Behaviors, researchers at UC San Diego School of Medicine and New York University investigated how use of these substances outside of medical settings relates to subsequent psychological distress, depression and suicidality.

They examined data from a representative sampling of noninstitutionalized adults (2015-2020) who had reported specific drug use on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, and whether that use was associated with any reported serious psychological distress, major depressive episode (MDE) or suicidality.

The researchers found that LSD was associated with an increased likelihood of MDE and suicidal thinking. Salvia divinorum, a plant species with psychoactive properties when its leaves are consumed by chewing, smoking or as a tea, was linked to increased suicidal thinking. The hallucinogens DMT, AMT and Foxy were associated with suicidal planning.

Sometimes called “Maria Pastora” or “Sally-D,” Salvia divinorum contains opioid-like compounds that induce hallucinations when the leaves are chewed, smoke or brewed in a tea. Researcher found the plant also induces an increased likelihood of suicidal thinking.

Conversely, ecstasy use was associated with a decreased likelihood of serious psychological distress, MDE and suicidal planning.

“The findings suggest there are differences among specific hallucinogens with respect to depression and suicidality,” wrote authors Kevin H. Yang, a fourth year medical student; Benjamin H. Han, MD, an assistant adjunct professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine; and Joseph J. Palamar of New York University. “More research is warranted to understand consequences of and risk factors for hallucinogen use outside of medical settings among adults experiencing depression or suicidality.”

— Scott LaFee

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (En Español: 1-888-628-9454; Deaf and Hard of Hearing: 1-800-799-4889) or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

Gene Therapy Reverses Effects of Autism-Linked Mutation in Brain Organoids

In a study published May 02, 2022 in Nature Communications, scientists at University of California San Diego School of Medicine used lab-grown human brain organoids to learn how a genetic mutation associated with autism disrupts neural development. Recovering the function of this single gene using gene therapy tools was effective in rescuing neural structure and function.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia have been linked to mutations in Transcription Factor 4 (TCF4), an essential gene in brain development. Transcription factors regulate when other genes are turned on or off, so their presence, or lack thereof, can have a domino effect in the developing embryo. Still, little is known about what happens to the human brain when TCF4 is mutated.

To explore this question, the research team focused on Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome, an ASD specifically caused by mutations in TCF4. Children with the genetic condition have profound cognitive and motor disabilities and are typically non-verbal.

Using stem cell technology, the researchers created brain organoids, or “mini-brains,” using cells from Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome patients, and compared their neurodevelopment to controls.

They found that fewer neurons were produced in the TCF4-mutated organoids, and these cells were less excitable than normal. They also often remained clustered together instead of arranging themselves into finely-tuned neural circuits. This atypical cellular architecture disrupted the flow of neural activity in the mutated brain organoid, which authors said would likely contribute to impaired cognitive and motor function down the line.

The team thus tested two different gene therapy strategies for recovering the functional TCF4 gene in brain tissue. Both methods effectively increased TCF4 levels, and in doing so, corrected Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome phenotypes at molecular, cellular and electrophysiological scales.

“The fact that we can correct this one gene and the entire neural system reestablishes itself, even at a functional level, is amazing,” said senior study author Alysson R. Muotri, PhD, professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

The team is currently optimizing their recently licensed gene therapy tools in preparation for future clinical trials, in which spinal injections of a genetic vector would hopefully recover TCF4 function in the brain.

— Nicole Mlynaryk

Post link

Harms of Vaping Hang in the Air

With the increasing popularity of e-cigarettes or vaping, there has been a concurrent rise in “e-cigarette or vaping product use-associate lung injury,” dubbed EVALI. In 2019, according to published data, more than half of patients diagnosed with EVALI in the United States required hospitalization.

In a paper published March 30, 2022 in the journal CHEST, a multi-institution team of researchers, including Laura E. Crotty Alexander, MD, associate professor of medicine in the UC San Diego School of Medicine and a pulmonary specialist, outline best health care practices for treating EVALI patients.

“Not long ago, there was tremendous interest in vaping-related lung injuries. But I think, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, many people believe this problem has gone away,” said first author Don Hays, MD, a pulmonologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“The truth is that it hasn’t. These injuries are still being seen, though we’re not positive on the frequency because the CDC has ceased collecting data since the pandemic began. The goal of this study is twofold: to provide information and guidance on treating EVALI patients, and also to put forth a reminder that this is still a problem.”

EVALI is characterized by respiratory symptoms, such as cough, shortness of breath and chest pain, combined with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. The new study reviewed CDC data regarding 2,708 confirmed or probable EVALI patients requiring hospital admission between August 2019 and January 2020. The study reported that 93 percent of the patients survived to discharge, but 88.5 percent required respiratory support.

Given that EVALI symptoms can be similar to common respiratory infections, such as influenza and COVID-19, the authors said it is important to determine whether a patient has a history of e-cigarette use, particularly within the last three months.

Alexander said the EVALI epidemic in 2019 was primarily due to the addition on Vitamin E acetate to e-cigarettes already containing THC, the psychoactive compound in marijuana, but also noted that e-cigarettes containing nicotine were linked to EVALI before and after 2019.

“We need to continue to warn both THC and nicotine e-cigarette vapers about the potential for acute lung injury,” said Alexander, who noted that UC San Diego Health averages two EVALI hospitalizations monthly.

“In health care, it is critical to be aware of, and understand, what’s going on in the public domain, in order to be suspicious of what might be happening with an individual patient. This is why public health is so important,” said Hayes. “The fact is, the average doctor may only see one or two EVALI cases, so by utilizing this panel of experts, who see EVALI cases more frequently, we’re able to provide guidance to questions like, ‘What should we be doing, how do we manage this, and should we be doing certain types of diagnostic tests?’”

Alexander agreed: “As clinicians become more aware of the health effects of e-cigarettes, we are hopeful that more accurate inhalation histories will be taken and documented, allowing us to accurately quantify e-cigarette driven diseases and outcomes.”

— Scott LaFee

Post link

Excess Neuropeptides Disrupt Lung Function in Infant Disease and COVID-19

Excess fluid in the lung can significantly disrupt lung function and gas exchange, but researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine were surprised to find that neuropeptides may be to blame.

In a study published March 17, 2022 in the journal Developmental Cell, scientists show that excessive neuropeptide secretion by neuroendocrine cells in the lungs can lead to fluid buildup and poor oxygenation. However, blocking the neuropeptide signals with receptor antagonists prevented the leakage and improved blood-oxygen levels, suggesting that neuropeptides may be a promising therapeutic target for conditions marked by excess lung fluid.

This mechanism was discovered in the context of neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia of infancy (NEHI), a lung disease affecting infants in which lung size and structure appear normal but blood-oxygen levels are consistently low. Its defining feature is an increase in the number of pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNECs), but until now, physicians did not know how these cells contributed to the disease.

In the new study, researchers confirmed that PNECs and their neuropeptide products are the drivers of NEHI, but also showed that PNEC numbers were increased in the lungs of COVID-19 patients with excess lung fluid. This suggests a similar mechanism may contribute to COVID-19 symptoms.

The study was led by Xin Sun, PhD, professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and the Division of Biological Sciences.

“We were surprised to find that neuropeptides can play such a major role in gas exchange,” said Sun. “Researchers are just starting to appreciate the relationship between the nervous system and the lungs, but the more we understand it, the more we can modulate it to treat disease.”

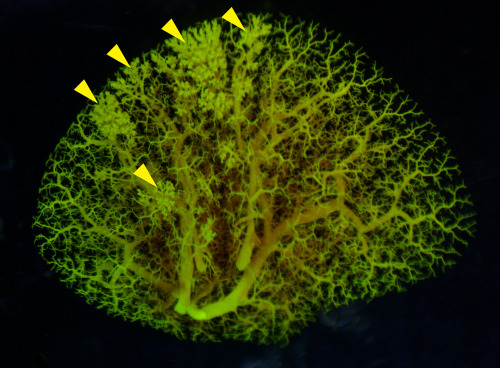

Pictured above: An angiogram of blood vessels in the NEHI mouse lung shows multiple sites of fluid leakage, marked by yellow arrowheads.

— Nicole Mlynaryk, Bigelow Science Communication Fellow

Post link

All of UsAdvances

Officially launched in 2018, the All of Us Research Program represents a massive, long-term effort to gather information from 1 million or more persons living in the United States, then use that data to accelerate health research and medical therapies. The biggest emphasis is upon gathering information on racial, ethnic and cultural groups who have historically been underrepresented or ignored in medical research.

Today, the sponsoring National Institutes of Health announced the release of the first genomic dataset generated by All of Us: nearly 100,000 whole genome sequences encompassing diverse individuals that can be used as a national resource for studies covering a wide variety of health conditions.

UC San Diego is part of the All of Us program, led by Lucila Ohno-Machado, MD, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Medicine, chair of the Department of Biomedical Informatics at UC San Diego Health, and associate dean for informatics and technology.

“As modern medicine seeks to become more precise and personalized, it necessarily requires more and more data to both understand the big picture of health and disease and, more specifically, how each person fits into the whole,” said Ohno-Machado. “With this first public genomic dataset, All of Us begins to meet its goals and expectations, allowing physicians and scientists to parse the mysteries and challenges of diseases across the health spectrum in new, individualized ways.”

— Scott LaFee

Post link

Sequencing Celebrity Mice: New Study Compares Genetics of 14 Popular Mouse Models

In a new study published on March 9, 2022 in Cell Genomics, researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine present a genome-wide map comparing the genetic makeup of 14 common strains of laboratory mice.

In the century since the C57BL mouse strain was first generated, it has become the most popular laboratory rodent for biomedical research. It functions as a sort of “default” mouse, and its genetic makeup is commonly used as a “neutral” backdrop for genetic modifications that model human diseases. The specific C57BL/6J strain from The Jackson Laboratory is currently the most commonly used inbred mouse, with a closely-related C57BL/10 strain widely used in fields, such as immunology. Many additional sub-strains have since been derived from both.

Given the prevalence of these mouse strains in biology research, a comprehensive understanding of their genetic similarities and differences is valuable to researchers, but until recently, such a resource did not exist.

A team led by Abraham Palmer, PhD, and Jonathan Sebat, PhD, professors at UC San Diego School of Medicine, has now identified 352,631 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 109,096 small insertions and deletions (INDELs), 150,344 short tandem repeats (STRs), 3,425 structural variations (SVs) and 2,826 differentially expressed genes (DEGenes) among the different strains. Most of the SNPs were clustered into 28 short segments in the genome, indicating that these genetic differences are likely due to an early introgression of an unrelated mouse, rather than recent independent mutations.

The authors say these results can now be used to guide both forward genetic approaches (wherein scientists identify a phenotypic difference between mice and look for the genetic variation that caused it) and reverse approaches (wherein scientists first identify a genetic difference and then assess whether it produces a different phenotype). Either way, they urge researchers to be aware of the unique genetic profile of their strain of choice.

— Nicole Mlynaryk, Bigelow Science Communication Fellow

Post link

When Viruses Become More Virulent

The evolution of virulence depends on the biology and interplay of infection and transmission, writes Joel O. Wertheim, PhD, associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Public Health at UC San Diego School of Medicine, in the journal Science.

Virulence is the degree to which a pathogen weakens, sickens or kills its host. More virulent pathogens may be less transmissible because in killing its host, it reduces the opportunity for transmission. But both virulence and transmissibility are forever linked: To maintain or increase infectiousness, a pathogen must be virulent.

In his Science article, Wertheim describes the emergence of a more virulent and transmissible variant of HIV that has spread to 102 known cases, mostly in the Netherlands. These findings, he says, have relevance to SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s possible that the coronavirus is evolving toward a more benign, highly transmissible infection, similar to common cold viruses, but that outcome is not guaranteed.

SARS-CoV-2 has displayed an extraordinary ability to rapidly alter its transmissibility and virulence, and how those two factors interact over the coming months will dictate whether SARS-CoV-2 will benignly fade away or continue to be an evolving, global public health threat.

– Scott LaFee

Post link

Brain organoids provide insight into the mechanism of a difficult-to-treat seizure disorder

Brain cells, or neurons, communicate through organized electrical bursts to control body processes like walking, talking and breathing. Sometimes, those electrical bursts can become disorganized and cause seizures, or epilepsy if the seizures are recurring. Focal cortical dysplasia — a brain disease characterized by abnormal balloon cells in the outer layer of the brain — is the leading cause of medication-resistant epilepsy. Some cases are caused by spontaneous genetic mutations, but the majority have an unknown cause. Treatment options are limited to invasive brain surgery, which may be ineffective.

In a new study, published online December 27, 2021 in Brain, an international collaboration between teams of researchers led by senior authors Alysson Muotri, PhD, director of the Stem Cell Program at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Iscia Lopes Cendes, PhD, professor in the Department of Translational Medicine at the University of Campinas, Brazil, describe a new laboratory model for focal cortical dysplasia using small floating balls of human brain cells called brain organoids.

Using a method called “reprogramming,” researchers are able to take skin cells from a skin biopsy and turn them into pluripotent stem cells. These stem cells can transform into any cell in the body — even tissues like brain organoids — and retain the same genetic material as the patient that received the skin biopsy, making it easier to personalize medicine.

The lead author of the study, Simoni Avancini, PhD, generated brain organoids from stem cells derived from patients with focal cortical dysplasia and compared them to brain organoids derived from healthy patients.

The researchers mimicked several aspects of the disease using the new model. They observed abnormal neurons, abnormal balloon cells, less actively dividing cells and more electrical bursts between the neurons. The results suggested that, at least in these patients, spontaneous genetic mutations do not cause focal cortical dysplasia, and it may be caused by unknown inherited mutations.

Inside brain organoids are sunflower-shaped areas called neural rosettes. where cells divide and mature into neurons. Precursor cells divide and fill the inner circle. Maturing neurons grow out of that circle like the petals of a sunflower. To investigate why brain organoids from patients with focal cortical dysplasia had less actively dividing cells, the researchers zoomed in on those neural rosettes and discovered differences in the expression of ZO-1 — a protein that helps cells stick together.

Unlike brain organoids from healthy patients where ZO-1 forms a smooth outline around the inner circle, brain organoids from patients with focal cortical dysplasia show ZO-1 as disorganized points within the inner circle. This led the researchers to investigate RHOA — a gene that regulates ZO-1 — in diseased brain organoids, and they discovered decreased expression of this gene compared to healthy brain organoids, suggesting that the decrease in actively dividing cells is caused by abnormal RHOA regulation.

Overall, these findings offer new insights into the mechanisms underlying focal cortical dysplasia, write the authors.

“We hope that this model will be useful to test and screen new theories and new ideas regarding focal cortical dysplasia, as well as finding novel treatments for this condition,” said Muotri.

— Gabriela Goldberg, graduate student

Brain organoids derived from a healthy person (left) compared to a person with focal cortical dysplasia (right).

Click to watch a video with Professor Lopes Cendes.