#charles babbage

THICC BOI

Big brained Babbage.

The digital savage,

Whose dreams were far from average.

If only he’d had enough cabbage

To finish building his computer package.

Post link

“It shall be done by… STEAM!”

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage by Sydney Padua, 2015

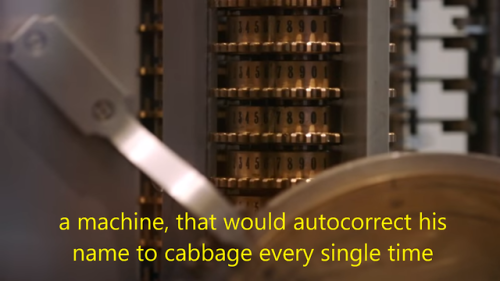

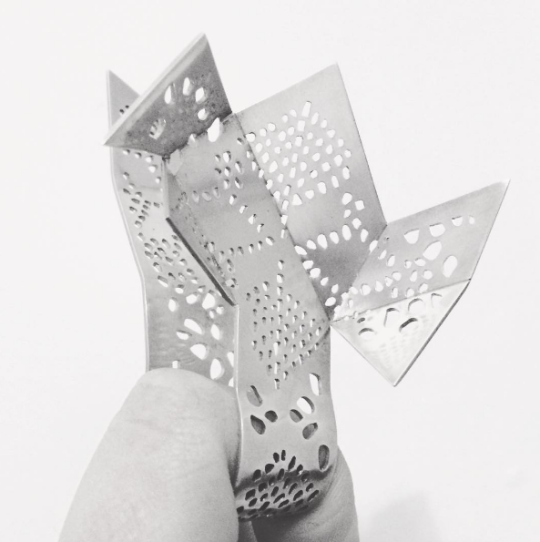

[IMAGE DESCRIPTION:

Two close-up photos of a difference engine, captioned with the text, “Babbage never foresaw the terrible consequences of his invention” and “a machine, that would autocorrect his name to cabbage every single time.”]

Post link

Weaving the Future: A conversation with weaver Soraya Shah and Natalia Krasnodebska, co-founder of Lady Tech Guild

Text by Natalia Krasnodebska

Film by Sara Kinney

In today’s tech savvy world, “luddite” refers to someone who is opposed to new technology. The term stems from a rebellion by English textile workers in 1811 protesting new power looms they feared would end their livelihood [1]. I’ve been working with various emergent technologies dependent on computing since 2008–so I’m hardly a luddite–but I was surprised to learn the link between weaving and software, which drives all the digital manufacturing I love and use.

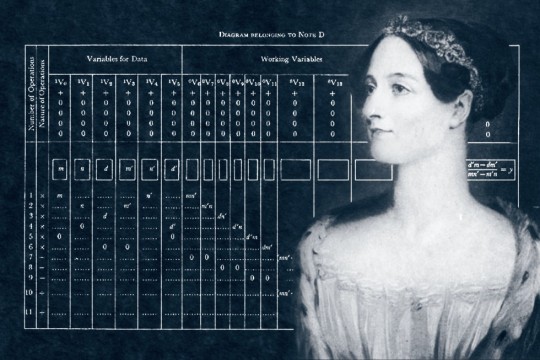

In 1801 Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a power loom that could base its weave (and hence the design of the fabric) on a pattern automatically read from punched wooden cards. Jacquard’s technology was revolutionary to mill owners [3], but more importantly it became the basis of code. Code, at its simplest, is just a system of symbols representing something. The punch cards created a system for placing individual threads in a fabric; a few enterprising people saw the potential beyond thread.

“Technology is just a tool. What are you going do with it? The artist is everything.”

Across the channel, English mathematician Charles Babbage was working on a steam driven calculating machine, the ultimately doomed ‘Analytic Engine’. He used Jacquard’s punch card idea to rework his machine. He even named components of it the “Store” and the “Mill”, which we now know as the “memory” and “CPU” of a computer. His friendship with Ada Lovelace led her to writing programs for the still unbuilt machine [2] and being credited as the world’s first computer programmer. Drawing on their ideas, American Herman Hollerith further advanced computing and ultimately founded a company based on his findings. That company was IBM and it would start the computer revolution. While IBM didn’t invent the personal computer (the honor belongs to Apple’s Steve Wozniak), it was the first to bundle it with software and thus put the power of technology in the hands of individuals.

Computers, and their software, have become ubiquitous parts of our lives, and the pace of technological revolution increases at an exponential rate. People marvel at smartphones, the internet, virtual reality, 3D printing and all that they can do to help advance the human race. Alongside this wonder is an attendant niggling fear that technology will take over our lives with Artificial Intelligence, the singularity and a robot uprising. We are seeing a worldwide return to appreciation for the artisanal, handcrafted, and seek connecting with objects around us. We love meeting the artists and makers and learning the story of their “one of a kind” items. We then snap artfully arranged pictures of a unique hand-thrown porcelain using a…smartphone. We carry the power of a million of Charles Babbage’s Analytic Machines in our pocket. And we use them to Instagram brunch.

Instagram may not be fully using the technology’s potential. But what is? How do we harness technology to serve us beyond apps? Can we combine our love of art and our love of technology? To unravel this question, I went to the source. I went to talk to a weaver.

Soraya Shah is an accomplished handwoven textile designer and Vice President of The New York Guild of Handweavers. Her weaving studio is based out of Studio Four NYC, a carpet, fabric and wallpaper showroom and design studio. For the past 11 years Soraya has been working closely with interior and architectural designers to weave custom and bespoke textiles for their interior and architectural projects. All of her goods are hand woven here in the USA.

Natalia: Your studio is so beautiful! What do people think when they come in here?

Soraya: Seeing the process allows people to appreciate the fabric I make in a different way, they ask Wow people still do this by hand? With my loom set up in the showroom, I’m able to sell fabric but I’m also able to show how it’s made, which adds a lot of value and consideration when clients are looking to order custom pieces. It was important to us to set up the weaving studio in the showroom as it helped to answer clients inevitable questions about why this is so expensive and why it takes so long. This setup is unique in our field, and it is also a defiance to our industry. People want everything fast, cheap and easy. I’m sitting here hand weaving to say art takes time; beauty is expensive. Wait, it’s worth it.

N: I’ve been trying to understand the link between weaving and computing. If code is a system, what’s woven fabric?

S: Weaving is the concept of taking thread and creating a grid like structure with it. Woven fabric is a cloth made up of two groups of threads, the warp and weft. These two groups interact with one another at 90 degree angles, the grid. This type of fabric is produced on looms by weavers.

N: Like this one? This isn’t a Jacquard loom?

S: No. Weaving has actually been around since before biblical times. Before floor looms like this, there were frame looms and backstrap looms. Then came the Jacquard looms. My loom is a Compu-Dobby loom. Dobbys were originally created in the 1840’s, in part to simplify the Jacquard process. This one has 24 harnesses and is computerized. Like the various 3D printing technologies, different methods of weaving give different results. A Jacquard loom gives you control: you can create shading, curves and even organic shapes because each warp thread can be controlled independently. The Dobby loom was developed in part to get it done faster and cheaper. There are a lot more limitations to what you can create, which I personally like. For me, structure is the foundation of everything.

N: I agree, limitation helps creativity. But going back to this loom, it’s a really complex machine! How do you get 24 individually threaded harnesses to become fabric?

S: I code it, I tell the loom what to do. First, since my loom is computerized I’m able to use a program to design and block out thread interactions to create the pattern I want. As well as the pattern, as I design, I am mindful of structural stability too.

N: How does technology influence your process?

S: I couldn’t do what I do without the technology but I don’t think it could exist without me either.

I draft the pattern and write the code so my loom and computer can communicate, but I power the loom with my body. I throw the shuttle, beat the weft in, my feet operate the treadles which drives the interaction between the loom and the computer, through a solenoid system triggered by my treadeling. I’m the translator.

The process begins with cones of yarn and a warp that I make by hand. I use a warping board to measure out yardage and the width of what I’m going to make. The warp then gets threaded on to the loom, through the reed and through the heddles. I use my hands and my bodyweight to comb out knots and which allows the yarn to wind on smoothly. Once the yarn is wound on to the loom and threaded through it, I tie the ends onto a dowel connected to the front of the loom and balance out the tension by making knots. I then turn on the loom and the computer and start to weave. As a weaver I respect every thread and every part of the process. That is how you make precise cloth. Add to that an even beat - that’s the hand of a master. That’s weaving.

N: How did you get into weaving?

S: As a child we used to drive up the Otavalo markets when I lived in Ecuador, that is where I saw tapestry weaving for the first time. To me, those textiles looked like drawings made with thread. After that everywhere I lived, cloth was something that stood out to me. How it varied from culture to culture. I moved to the US when I was 19 to study Illustration at Savannah College of Art and Design but I found myself drifting into other disciplines and ended up in a Fibers class and never looked back. I had an incredible professor named Doris Louie, she said it before I even knew it: “You’re a weaver”.

In the middle of college, my grandfather died. I was devastated, and weaving helped me deal with the grief. I went to his funeral in Trinidad and was in awe of the hundreds of people that attended, all people that his life left an impression on. I thought about how threads, as they are woven into fabric, leave an impression on each other. When I take fabric apart, I’m seeing fabric become yarn again, but those yarns are left with the impressions of each other on them. That’s so fundamental to people, to our history, our culture, and our stories. We change each other, every interaction leaves an impression. Cloth is the ultimate representation of that. Cloth holds our history.

N: That’s beautiful. With your weaving, you seem to be making order of our chaos, both literally and figuratively. Are you weaving yourself?

S: There is always a piece of me going into the fabric. I am chaotic! Even before I started weaving, I was always drawn to the things that disgust and disturb me. I can not tell you how many fabrics I’ve made based on one color that grosses me out. It might be a color, a fiber, a pattern or an idea that doesn’t sit right with me. I have to find a way to make it beautiful. Ultimately for me, the draw was defiance. Everything I make is a form of defiance. I’m impatient and have short attention span, I’m terrible at math. Everything about weaving requires patience, attention, time…math.

Speaking of math, what drew you into creating the jewelry you make, which then led you to using 3D printing to create it?”

N: While studying goldsmithing I was reading the “Poetics of Space” and was drawn to the idea of negative space. I started making a lot of thin, precise shapes. Unfortunately, the human eye is incredible, if my line was even a fraction off, you could tell it wasn’t straight. I made a lot of wonky squares before I realized my technical expertise needed another 40 years of practice. Ultimately your eye is better than your hand.

Around that time, I read about this emerging thing called 3D printing. I taught myself to 3D model and signed up for the beta test of a company called Shapeways, who were kind of like Kinko’s for 3D printing–using expensive industrial machines and making them available to the public. I sent them my 3D file, and they sent me back a precise, perfect 3D print.

When I unpacked that first 3D printed piece I was transfixed. This was exactly what I imagined, what I had designed, and that to me was the magic.

The head of our department, Robert Baines, was worried that this technology would destroy jewelry as a field. But to me the technology was just a tool, like calipers, or a saw. He taught us to be craftspeople, and the importance of designing for the body. Inherent in our design process was the wearer and the method of production. Today, the RMIT jewelry department is still going strong, and they now incorporate 3D printing as a method of production alongside traditional techniques.

3D printing let me combine art and technology, and gave me the precision I was lacking. As I got to know more about the process I was able to work with the machine more, and I admire people who are really taking advantage of it to push the boundaries of art and design. People like Jessica Rosenkrantz of Nervous System, Iris van Herpen, Bathsheba Grossman, Anouk Wipprecht, Francis Bitonti and Bradley Rothenberg.

The artists that use 3D printing in creative and novel ways have artistic vision AND they master the technology, and so bend it to their will. Soraya, you do that too! By programming your loom, you combine art and technology, and you take advantage of the process. This takes time and patience, because if you don’t understand the process you can’t take advantage of it. In both our fields, we rely on the machine to automate only part of our process.

You mentioned that the loom you use was designed in the 1840s and it hasn’t changed much.

That’s the same with jewelry using fire since 2BC; both our techniques are basically unchanged since they were invented. The challenge now is to incorporate digital techniques, the same way we have incorporated previous tools as a human race. I’d argue that technology is just another tool in an artist’s hand.

“To be a good artist you have to have vision and talent, to do production you have to have the technical skill and to be a true craftsperson you need an understanding of both.”

S: Exactly! What changes is the “translator”, the artist. Faced with the same technology, the same tool, an artist today does something different than an artist did ten years ago. Weaving is an ancient craft and it’s important to honor the history of the process. I always feel new, like I’m just dipping my toes in the weaving pool. It makes me humble, but also drives me. I’m an artisan, I’m not reinventing weaving, but I am injecting traditional woven pattern with Soraya flavor.

N: So what is the point of artists if we have intelligent machines?

S: We power the machines. We build them, we tell them what to do. When we worry about technology taking over our lives, let’s not forget where the power lies.

N: So you, the artist, are actually integral to this technological process?

S: There is always an element of the artist’s hand in weaving, even in computerized weaving machines, because they are threaded by hand; there are people running the machines. There is a misconception that mills just “make” complete fabric or products.

N: We have the same misconception in 3D printing, that the machines “make your ideas come to life”. The 3D printing industry has been selling this dream “If you have an idea we will make it a reality! You can have whatever you imagine, right now!” and it’s misleading.

S: Right! That’s only half the story. The artist makes the blueprint, then executes the plan and oversees production by the machine. The machine just does what I tell it to do. If you design without thinking of production, it won’t work. Good design is nothing without good production.

To be a good artist you have to have vision and talent, to do production you have to have the technical skill and to be a true craftsperson you need an understanding of both.

–

We live in a fertile time for art and technology collaborations, but they are not new. From the camera, to silkscreen printing to virtual reality, technology changes how art is made. Artists have been an intrinsic part of technological evolution.

Occasionally, it’s embodied in one person like Leonardo da Vinci: an artist who also gave us some useful inventions. Today, it’s people like Soraya Shah. Far from being at odds with each other, the divide between (wo)man and machine is getting smaller and smaller; Soraya and her loom embody the “increasingly meaningless standoff between hand and machine” [4].

Perhaps Instagram photographers are the best expression of the Analytic Machine after all. If we want to harness the power of technology, place it in the hands of artists. As Soraya put it: “Technology is just a tool. What are you going do with it? The artist is everything.”