#elegy lament in the 20th century

Doris Caesar once said, “I try to be emotional, and yet get away from reality.” Characteristic of her expressive work, this figure is elongated and gaunt. The surface of the piece is covered with marks left by the artist’s hands as she worked the clay that would later be cast in bronze. With her slumped posture, drooping shoulders, and downturned facial features, the widow’s body appears to convey the emotional weight of her grief.

See this sculpture in our newest installation “Elegy: Lament in the 20th Century.”

“The Widow,” around 1930–50, by Doris Caesar

Post link

Barbara Chase-Riboud created this monumental sculpture by combining angled bronze forms with bundles of wrapped and knotted fibers. The artist was living in Paris at the time, having moved there in 1960 from her birthplace of Philadelphia. Even though she was abroad, the events of the civil rights movement in the US greatly affected Chase-Riboud and inspired her to dedicate a series of sculptures to the Black Muslim minister and activist Malcolm X. “Malcolm X #3” is a tribute to and celebration of the leader, rather than an icon of mourning. The series was not meant to represent the man in a literal sense or to lament his assassination. The artist instead created the sculptures on an aesthetic basis and dedicated them to Malcolm X as an historical person.

See this sculpture on view in our new exhibition “Elegy: Lament in the 20th Century.”

“Malcolm X #3,” 1969, by Barbara Chase-Riboud © Barbara Chase Riboud

Post link

Using found materials such as mop strings and broken glass, Thornton Dial, Sr., created this monumental, abstracted representation of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., exploring the intersection of the secular history of King’s assassination and the sacred history of Christianity. The central tiger—Dial’s primary emblem for representing Black men in his early work, because of the cat’s survival skills—symbolizes King on April 3, 1968. In the lower left-hand corner, we see with a table set with metal pots and pans, representing the Last Supper—the final meal Jesus shared with his twelve apostles the night before the Crucifixion—and signifying the impending murder of the civil rights leader.

See this work on view in our new exhibition “Elegy: Lament in the 20th Century."

”The Last Day of Martin Luther King,“ 1992, by Thornton Dial, Sr. © Estate of Thornton Dial / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Post link

Dorothy Norman was born in Philadelphia on this day in 1905. In 1927 she met and began collaborating with photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz. Norman made this photograph of Stieglitz’s final gallery, An American Place, shortly after his death. Unbroken planes of light on empty walls seem to highlight his absence.

See this photograph in our installation “Elegy: Lament in the 20th Century.”

“From the Window of An American Place after Stieglitz’s Death,” 1946, by Dorothy Norman

Post link

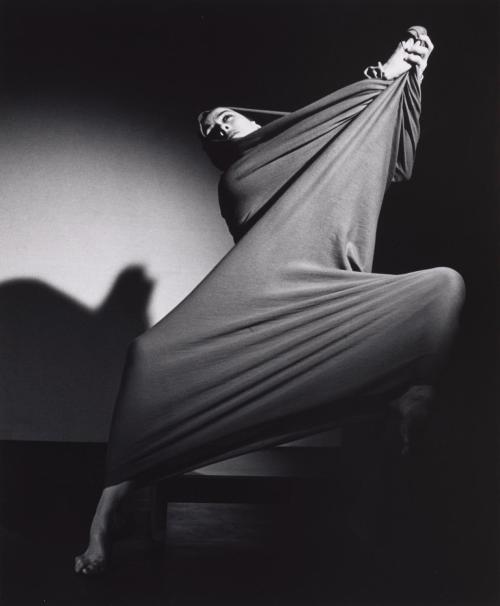

Barbara Morgan described the performance “Lamentation” by Martha Graham as a “dance of sorrow … the personification of grief itself.” Working to portray the melancholy essence of the dance and to capture its “visual peak,” Morgan produced a dramatically diagonal image of the American modern dance pioneer. Though Graham leans on a bench, her arms and legs extend expressively to stretch the dark fabric that envelops her—a material that, according to the dancer, “indicate[s] the tragedy that obsesses the body, the ability to stretch inside your own skin, to witness and test the perimeters and boundaries of grief.”

See this photograph on view in our newest installation “Elegy: Lament in the 20th Century.”

“Martha Graham - Lamentation,” 1935 (negative); c. 1981 (print), by Barbara Morgan © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

Post link