#francis fukuyama

How about that Lenin? Big reader. Loved books. Tolstoy: loved him. Goncharov: couldn’t get enough of him. Chernyshevsky: the best. But Tariq Ali notes that Lenin couldn’t hang with the avant-garde, and that this had surprising ramifications for the Russian Revolution: “Lenin found it difficult to make any accommodations to modernism in Russia or elsewhere. The work of the artistic avant-garde—Mayakovsky and the Constructivists—was not to his taste. In vain did the poets and artists tell him that they, too, loved Pushkin and Lermontov, but that they were also revolutionaries, challenging old art forms and producing something very different and new that was more in keeping with Bolshevism and the age of revolution. He simply would not budge. They could write and paint whatever they wanted, but why should he be forced to appreciate it? … Shortages of paper during the civil war led to fierce arguments. Should they publish propaganda leaflets or a new poem by Mayakovsky? Lenin insisted on the first option. Lunacharsky was convinced that Mayakovsky’s poem would be far more effective and, on this occasion, he won.”

This and more in today’s culture roundup.

Post link

If shitlessness is too taboo for you, there are other ways to jar and unnerve your potential readers. Take pains to pepper your prose with irregardless, for example, and watch the hate mail pour in. Jennifer Schuessler writes, “Irregardless is one of those words that people love to hate. No one is lukewarm about irregardless. I don’t use it, but what I love about it that it has hung around on the periphery of English for over 200 years. It’s like this barnacle that you can’t get off the hull of the language, and I think that’s great.”

This and more in today’s culture roundup.

(Image: Tony Luong for The New York Times)

Post link

Looking for a fun, easy way to spice up your writing? Try throwing in a fecal intensifier or two. They’re the shit, and you’ll be thrilled shitless with the results. As the translator Brendan O’Kane writes, fecal intensifiers are the idiom of the moment, but it’s hard to follow their logic: “A certain distinguished Dutch professor emeritus … noted that ‘people before about 1950 were mostly bored shitless.’ This cracked the room up, naturally, but it also seemed slightly off …I might be scared shitless, but I’m unlikely to be amused, bored, delighted, outraged, or annoyed shitless. This is curious, since shitlessness would seem to be the natural result of something scaring, boring, or annoying the shit out of me—all distinct possibilities, according to my understanding of the idiom. In particularly unexpected circumstances, one might even shit oneself—as a response to fear, outrage, amusement, or surprise, rather than delight or (unless as a last resort) boredom.”

This and more in today’s culture roundup.

Post link

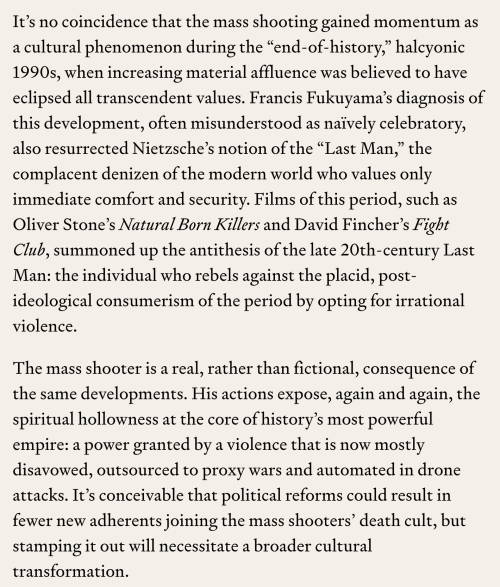

—Geoff Shullenberger, “The Faith of Mass Shooters”

Insofar as we need a cultural explanation, and not an MK-Ult(u)ra(l) one, this is probably it, not that those two possibilities are strictly inconsistent. For my take on how we can have Fukuyama-without-violence, see here (essay) and here(podcast):

The only way liberal democracy can fall short of humanity’s final political synthesis is if it too harbors an inherent contradiction necessitating further conflict. Now Fukuyama brings another alarming Teuton onstage to consider this possibility—for didn’t Nietzsche say that liberal society produces the bathetic creature he labelled “the last man,” a cow-eyed consumer so lost in complacent satisfactions that he lacks any thymos at all? (Nietzsche’s contemporary heirs—ultra-right-wing online shitposters—have their own pungent labels for this archetype: the soyboy, for instance, or the bugman.) And doesn’t this last man at the end of history eventually become so disgusted with himself that he begins to long for an apocalypse of the sort that ended Europe’s long peace in 1914 when the citizens of the nations clamored for a cleansing war?

Fukuyama says yes to this dire possibility. As a solution he proposes that liberal society must allow illiberal pockets in private life—religion, sports, art, etc.—to drain humanity’s incorrigible thymos away from the political realm while still satisfying our urge to rise up and be recognized as not merely equal to but better than our neighbors in at least some arenas. To put it more coarsely than he does, we may need a little fascism in our poetry or our football games or our church services to keep fascism out of the government.

For my response to Bataille, whom Shullenberger cites elsewhere in the piece, see here—limited to my reading of his most famous novel, all I’ve read of him, but enough to get the point. I took the excess violence or violence-as-excess in the pornographic novel more as prescription than diagnosis, but perhaps in that essay, significantly written and posted on the 7th of November 2016, I was being too moralistic:

Mothers and sisters—that is, female blood relations—are presumably sickening for Bataille because, like eggs, they stand for generation and their menstrual blood for the processes that generate life. The eye, on the other hand, stands for visionary perception, but it too must be debased because the eye’s idealism has in the western tradition also upheld life by associating it with a higher ideal, God or the Platonic forms or, simply, the truth. Bataille and his heroes are inverted Platonists, no less in love with an ideal, but a dark and negative ideal, an upside-down sublime, a mountain standing on its head, a photo-negative of the good, an anti-truth of the rapture of torture.

[…]

All in all, Story of the Eye is a typical piece of “French extremity,” to cite the film genre, a narrative tradition almost unchanged since the days of Sade, whose books I have never succeeded in finishing, and which continues onscreen today. Mechanically reversing the traditional pieties of the west like flipping a series of switches, the devotees of extremity have created a pious tradition of their own, carried on to a stultifying extent in the institutions of culture, particularly the art world and some wings of academe.

Post link