#russian revolution

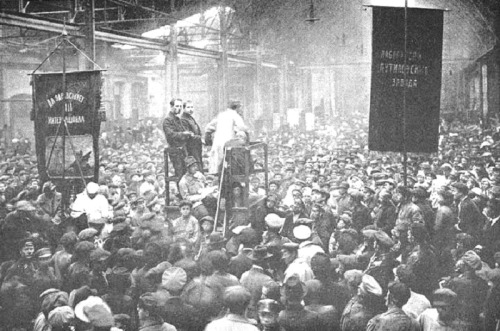

This fall, the Jewish Museum presents a rare opportunity to explore a little-known chapter in the Russian avant-garde. Opening on September 14, Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922features some 120 works of three iconic figures—Marc Chagall, El Lissitzky and Kazimir Malevich—as well as works by students and teachers of the Vitebsk school—100 years after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Post link

Final weekend—don’t miss your last chance to see Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922, closing this Sunday. Through the work of three iconic figures–Marc Chagall, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich–as well as works by students and teachers of the People’s Art School, discover how Vitebsk–a small city with a significant Jewish population–became an incubator of avant-garde art during a time of radical transformation following the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Post link

How about that Lenin? Big reader. Loved books. Tolstoy: loved him. Goncharov: couldn’t get enough of him. Chernyshevsky: the best. But Tariq Ali notes that Lenin couldn’t hang with the avant-garde, and that this had surprising ramifications for the Russian Revolution: “Lenin found it difficult to make any accommodations to modernism in Russia or elsewhere. The work of the artistic avant-garde—Mayakovsky and the Constructivists—was not to his taste. In vain did the poets and artists tell him that they, too, loved Pushkin and Lermontov, but that they were also revolutionaries, challenging old art forms and producing something very different and new that was more in keeping with Bolshevism and the age of revolution. He simply would not budge. They could write and paint whatever they wanted, but why should he be forced to appreciate it? … Shortages of paper during the civil war led to fierce arguments. Should they publish propaganda leaflets or a new poem by Mayakovsky? Lenin insisted on the first option. Lunacharsky was convinced that Mayakovsky’s poem would be far more effective and, on this occasion, he won.”

This and more in today’s culture roundup.

Post link

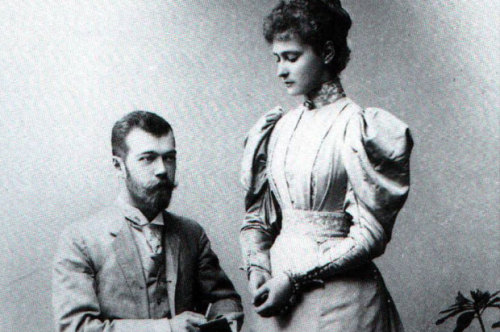

Set against the backdrop of revolutionary turmoil, featuring an opportunistic mystic and hinging on an incurable bleeding disease, their tale had all the melodramatic elements of a sensational opera. (Indeed, it has inspired at least two.) The granddaughter of England’s Queen Victoria, Alix Victoria Helena Louise Beatrice—later known as Alexandra Feodorovna Romanov—rejected an arranged marriage to her first cousin, Prince Albert Victor, after falling in love with Nicholas, heir to the Russian throne, as a teenager in 1889. Equally smitten, her lover convinced his reluctant, ailing father to agree to the union, and the pair wed in November 1894, just several weeks after the czar’s death and Nicholas’ coronation.

Though forged amid great sadness, the marriage was a happy and passionate one, producing four daughters and a son, Alexei. From his father the young czarevitch inherited the claim to the Russian throne, but his mother bequeathed him a more burdensome legacy: the mutant gene for the clotting disorder hemophilia, of which both Alexandra and her grandmother Victoria were carriers. Terrified of losing Alexei, his parents became increasingly reliant on the controversial “mad monk” Grigori Rasputin, whose hypnosis treatments seemed to slow the boy’s hemorrhages. Rasputin’s political influence over the czar and czarina undermined the Russian public’s confidence in the Romanov dynasty and contributed to its overthrow during the February Revolution in 1917. Nicholas, Alexandra and their children were executed on July 16, 1918, on orders from Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin. Indirectly, at least, the royal couple’s romance had opened a new and bloody chapter in Russia’s history.

Post link

Protazanov contributing to my intellectual laziness tonight — I thought some of you might also be interested to see… Cool movie!..:

Further whetting my interest in 1920-1930’s Soviet cinema, Part III of Kozintsev’s “Maxim Trilogy” — an excellent and intriguing work throughout. All of his films are for free/ subtitled generally reliably in English on YouTube. (Have to add that Dovzhenko, Pudovkin et al. are also found there.)