#jonny’s insect catalogue

Winter Firefly - Ellychnia corrusca

Let’s have one more set of pictures from the Muskoka visit to round things out, shall we? Not to toot my horn but I’m very proud of Picture 1 with opened wings and exposure to the abdomen hidden beneath the shell. Interestingly, there was a short pause after opening the wings before taking flight. Anyways, the beautiful night sky of cottage country (which is dotted with many stars unobscured by light pollution) is the perfect environment for the illumination of insects like this one. Or at least it would be if this specie of Firefly was able to light up its rear as the name might hint. For this specie, only the larvae and pupae can glow, the adults losing this ability upon maturation. It’s not all bad news though since this Beetle spends most of its time as a larva anyways, scourging around the leaf litter and under logs in search of insects and slug to eat. Their diet changes upon reaching adulthood, shifting from carnivorous to hungering for sap and flowers. If you go looking for the larvae, know that they are quite a rare find. Fortunately you’ll know them when you see them as they might glow and they closely resemble Trilobite Beetles. If you can’t find the larvae, adults will be more out in the open. They fly during the daytime and crawl about on trees, leaves and man-made structures.

The adults should be recognizable enough with the colors of their armor, their antenna type and their (relatively) large size compared to other Fireflies. The specimens you see before you are likely those that have emerged after an overwintering stint as adults. It’s the ability to survive the harsh winter that gave this Beetle its name, and with the weather turning warm, it’s time to find a mate. If the temperatures can hold steady, there could be a second generation, but these are another generation from the eggs laid earlier in the year. Nevertheless, the Fireflies that emerged from winter waste no time forming mating pairs. It’s not really possible to discern which Beetle is the female or the male in these pictures (you’d need to flip them over to check the final abdomen segment which would be quite rude). To avoid sitting on them, you can persuade them to climb on a stick and relocate them to a more green environment…as I did. I was called up to the balcony to investigate what looked like a Caterpillar, but was in fact the Beetles you see before you. I can sort of see the resemblance. They can move together (even turning without a break) to escape a perceived threat, though it looks more like one is taking the lead and dragging the other along. While transporting them, the leaders switched occasionally, resulting in a change of direction. Fascinating!

Pictures were taken on May 28, 2022 in Muskoka with a Google Pixel 4. For anyone interested in more information, I enjoyed reading this paper by Rooney and Lewis covering the Winter Firefly.

Post link

Racket-Tailed Emerald - Dorocordulia libera

As promised, another beautiful insect from the Muskoka cottage scene by the lake. This one has wonderful shades of metallic green on its thorax plates which make it a sight to behold if you find one. You may think that those vibrant colors are what give this insect its name, and while there is a bit of truth to that, the real answer is much more interesting, and I truly wish these pictures could showcase what I’m about to describe. Belonging to the family CorduliidaeorEmerald Dragonflies, this new family is a first for the blog, joining the quick Skimmers (Libellulidae) and the large Darners (Aeschnidae) (and the one Clubtail also found in cottage country). The Emerald family received their name from the vibrant green eyes that most species tend to display when they fully mature. You’ll need to look at other pictures for reference, but I promise you, these eyes are saturated with a lush light-green. This specie can have that eye color too, but sadly not this individual, which leads me to deduce that this individual may be an “immature” adult, needing a little more time in the sun.

While other Dragonflies have differing male and female characteristics, both males and females can have green eyes, at least from what I’ve read and seen. This in mind, there’s a much easier way to tell male and female Emeralds apart: look to the tips of their abdomens! No matter what eyes they have, the males will have three prominent claspers and females have an elongated plate and/or diminished claspers on the abdomen tip. The pictures here don’t really show the best view of the abdomen, but I see no claspers. With this information in mind, I’ll know what to look for next time. Continuing on, as the name suggests, the widened tail tip has given this beautiful creature its name, “racket tail”. Keep an eye out for this feature if a green-eyed Dragonfly zooms by you. Also, while the top of the body shows greens of various intensities, the undersides of this Dragonfly are striped with yellow. She is truly stunning and will likely go on to birth several new Dragonflies that will call the lake in front of the cottage home in their young naiad forms. After spending their days hunting prey in the water, they too will emerge will emerald coloration to hunt the many flying insects of the cottage environment. MidgesandMosquitos provide an all you can catch buffet for them, and there are larger insects to try and catch such as the elusive Alderfly.

Pictures were taken on May 28, 2022 in Muskoka with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Common Snipefly - Rhagio mystaceus

I’ve just returned from a cottage trip up in Muskoka with many insect pictures to share. With the weather turning warmer across Ontario, many new insects have begun to emerge. Especially those insects that aren’t too far from the wooded areas or lake Muskoka. It’s still a bit too early for everyone to come outside, but there were May Beetles flying headfirst into the cottage’s walls, having been drawn in by the night lights. Night lights also draw in Crane Fliesand Moths (latter identification is ongoing) which have plenty of places to perch and rest thanks to window screens. In the daytime, other insects can be found rummaging and flying around cottage country including the subject of today’s post. I’m reluctant to post about another Fly so soon after the last one, but it’s another new specie for the blog and may serve as an educational tool for those in cottage country, the woods or marshes. Plus, it’s not every day that I find a Snipe Fly sporting beautifully patterned wings and posing for nice pictures. This specimen is a female which can be discerned by the gap between its compound eyes. Comparing it to the other species of this blog, it has the classic Rhagio Snipe Fly body shape and long legs. When first finding it, I wasn’t sure what this insect was, and I wouldn’t be sure until closely looking at Picture 2 and noticing a long, tapering abdomen with faint yellow stripes.

I was hesitant to approach at first. Why? Cottage country can be notorious for biting Flies, especially in areas by lakes, woods and fields. Specifically Deer Flies and Horseflies, both of which tend to present with patterned wings. Muskoka definitely has Horseflies, but this is too small and spindly to be that, so I pondered whether this was a Deer Fly. Thankfully not, as Deer Flies tend to have bright, metallic eyes with scintillating patterns. Breathe a sigh of relief if you see this Fly near you as this specie is reported not to be frequent biters (if at all) of humans. Other species of the west may bite, but not to the same degree as a Horsefly. The Snipe Fly mouthparts seem to be for jabbing rather than slicing. Getting off that subject, I’ll end this post by mentioning that this insect has a look-a-like that you should be aware of: R. punctipennis: the Lesser Variegated Snipe Fly! To tell these two down-lookers apart, pay close attention to the wings and thorax. The wings are patterned differently and thorax’s parallel bands are different too. The Common Snipe Fly has a little divide in between the middle band (zoom in on Picture 5) and the scutellum appears discolored compared to the scutum (smaller thorax plate compared to larger thorax plate). It’s much less complicated than it sounds, trust me, but the take away here is that this Fly isn’t likely to bother you during a cottage summer day.

Pictures were taken on May 28, 2022 in Muskoka with a Google Pixel 4. Another Muskoka cottage insect will come on Friday. A larger, more metallic insect will be examined. Which one could it be?

Post link

Golden Dung Fly - Scathophaga stercoraria

The more Flies I find while out looking for insects, the more surprised I am to find new varieties and families within their order, Diptera. Today’s post is a new specie and opens up another new family for this blog to explore: Scathophagidae. More commonly they are called Dung Flies, but researching into this family suggests that this common name is a bit of a stretch as not all Flies within this family have an appreciation for dung. It can be tough to narrow broad spectrum characteristics into a family name. The only name I could think of would be “Hunter Flies” given the diet of the adult, but this might tread on Robber Flies, which, in my opinion are the more vicious predatory Flies. The latter exemplify hunting with that sharp facial spike and their aggression, but this Dung Fly is no slouch to hunting. There’s great footage online with this specie slowly approaching other Flies at rest and then rushing them and trapping them with their enlarged spine covered legs. The only thing I’m confused on is their mouthpart. Looking at macrophotography and videos of the Fly hunting, it looks like it has a sponge mouthpart (labellum) on the end, but the mouthpart as a whole looks like a short and blunt pencil tip. I’m very curious to seeing how exactly it lands the first blow upon capturing a Fly or similar insect.

Regardless of how it manages to nab its way, the where it interests me. When hunting, the hungry Fly waits from around flowers, leaves or dung to attack insects. Blowflies such as the Greenbottle Fly are on the menu given their attraction to both, and I fear that Hoverflies may also be on the menu too! Let’s hope their striped patterns can give this Fly the slip. Whether hunting or waiting for a potential mate, this individual was vigilant over a pile of dog poop and remained on plants nearby. Had I known what this specie was, I would’ve stayed around a bit longer to see if it catch something. The adults won’t eat the dung as a primary food source, but they are drawn to it, and eggs laid inside it (for this specie). Other species within Scathophagidae lay their eggs on other things found in nature such as on plants, in water and some even parasitize other insects. The only thing I can think of that all these sites have in common is a lot of moisture (which is handy to ward off drying out). All this variety of habits and preferences and yet poop is the main focus of this family. With this particular specie being a common find in the wild and well studied in research, it may have influenced the naming of this family.

Pictures were taken on May 19, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Lucia Azure Butterfly - Celastrina lucia

Here’s a fun-looking specimen, and a more glamorous find along Toronto’s lake shore. I’m not entirely sure that I’ve chosen the right insect here as Azure/Blue Butterflies look very similar to each other, requiring close inspection to be sure. I’ve chosen the insect as Lucia Azure due to the habitat range and time of emergence. Embarrassingly, I had the insect pegged as the Summer Azure (C. neglecta) initially. Yes, that’s how similar these insects are to one another! Especially looking at the patterns on the underwing. The name should’ve been a giveaway, but it was worth exploring and researching anyway to learn more about this branch of Gossamer Winged Butterflies, which is otherwise a large insect family. Yes, the Summer emerges as an adult in summer, meanwhile this specie emerges during spring after an overwintering. If you find a Blue or an Azure, observe it very carefully and look for any features that may help determine what you’ve found. Even the flowers it feeds from or the plants that it hovers around!

While it looks peaceful and content on the sandy dirt, let me assure you that this insect is quite jittery and takes off at an alarming speed! Trying to follow it around, it darted around the grass and dandelions in the area, eventually settling on the dirt…and then launching away as soon as I’d bend down to take some picture. If approaching a Butterflylike this one, take your time and approach slowly. No sudden movements! If the opportunity should arise, you can even catch it in your hand with an open grip, upon which it will take again! While it’s skittish and eager to escape, it’s actually quite easy to keep an eye on it for tracking purposes due a detail not shown in these images. As the name suggests there’s a blue color that makes this insect very noticeable in flight from the scales on the dorsal side of the wings. But when folded upwards at rest, the patterned wings do a good job of blending into the stone-scattered sandy terrain. While other Butterflies can mimic leaves, this one can hide on the ground at the right angle, but I think it would need to be careful about choosing its moments to fly away.

Pictures were taken May 15, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Eastern Boxelder Bug - Boisea trivittata

I’ve developed a large stockpile of Boxelder Bug pictures to upload over the years, but despite how frequently I find them in my area, They’re some of the first insects to be food in the early spring (crawling in the leaf litter) and some of the last insects to grace the autumn (eventually making their way to the leaf littler); 2 generations make them easy to document and photograph. I’ve never sought to record them in motion. With today’s video, that changes. Taking a walk in a wooded area, I noticed that there were Boxelder Bugs galore! Not quite swarming, but there was tremendous activity on the goldenrod plants and in the dried grasses. Perhaps they were looking to secure territory and mating spots? The timeline would fit, and hopefully the nymphs are positioned near a suitable plant to satisfy them, While named after their host plant, it seems that maple tree juices are a source of food for them too! With this video, we can examine and observe how the insect moves on and reacts to the surfaces it struts along. While exploring the hand was a new experience for it, it seemed more than eager to return to the young goldenrods and hide from me. What interested me the most when revisiting the footage at home was how the insect’s antennae orient themselves when the Bug is on the move and at rest. It’s always sensing where to go next and getting a feel for its surroundings.

Video was recorded on May 19, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4. As well, B. trivittata will be known as the Eastern Boxelder Bug rather than just Boxelder Bug. This is to futureproof for later Boxelder Bug posts with new species. Prior posts have been adjusted to the reflect this change.

Midges - Family: Chironomidae | Species unknown

Afterlast week’s video post showcasing these insects and their dancing formations over flowing water, this week we’ll attempt to get a closer look at them. It’s funny how the insects seem of reasonable size when you actually hold or see one, but when looking at them against the sky, one could be mistaken to thinking that it’s just birds flying in the distance. Each speck represents one Midge flying around so there’s probably 50 or so in picture 2. Those are rather small, and actually very close, but not all Midges are so tiny. Some are larger, and there is a size difference between females and males. Based on what I’ve read females are larger, but the males have plumose antennae. More than a decoration for their appearance, they (similar to Moths) use those feathered antennae to help them find a mate. Looking at the individual I’ve caught in Pictures 1 and 10, you can get a closer look at the features. Take note of the elongated body, shortened wings, feathered antennae and the positioning of the front legs. Though a bit roughed up from the capture, this hardy fellow was able to fly away after a few pictures. These are non-biting Midges, which may imply that there are biting Midges…and yes there are. Those belong to the family Ceratopogonidae and some do bite humans.

As said earlier, they are drawn to bodies of water and moist environments as those places are beneficial places for the placing of eggs. The adult Midges need to get to work quickly as they usually live for a few weeks, if that long. Depending on the specie, they may not even feed when they are adults (some take honeydew or nectar), so the timing is quite urgent. Fortunately, they can mitigate most risks with simultaneous emergence (again, it depends on the specie) and the emerge of massive swarms. While annoying for boaters, bikers and visitors of a waterfront, the sheer numbers of Midges allow more than enough to survive to ready the next generation, even if a few get caught in spider webs or eaten by other predators. They lack defenses aside from their flying prowess, and since they’re often mistaken for Mosquitoes, they can be eaten or swatted at with little thought. While similar in appearance to Mosquitoes and closely related to them, these non-biting Midges don’t have a taste for blood and have a few differences that you can use to tell them apart, all of which can be found in the first paragraph of this post. The front legs should stand out immediately, and as such both insect groups have different postures when landed.

Pictures were taken on May 11 and 15, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Midge Swarm - Family: Chironomidae | Species unknown

Please view this in HD to not obscure the insects behind resolution pixelization. There’s no insect close ups in this video, but instead the dance to see a swarm of insects that recur year after year. Over bodies of water, adult Midges emerge and swarm to find mates. It’s a bit of a common sight in Ontario as the seasons shift into spring. If this is what they’re like here, can you imagine the amount of little Flies that cottage country sees? Goodness me! Potentially numbering in the hundreds over here, they can certainly get in your way as you’re walking around near a body of water. I sometimes see masses of them hovering over the pine bushes in the front yard, especially before or after rain. Seems moisture is the key to their success. Fortunately, while these Midges can make visibility difficult, these are not biting insects and do not need to be avoided in the same way Mosquitoes would be. That’s a good small miracle. To otherwise prepare for these spring swarms, make sure your window screens are in place, wear some goggles or glasses, and bring a net if you want to try capturing and observing a few members of the swarm. The midges in particular are tiny, black, somewhat long-legged and have transparent wings. When swinging my hand through the insect cloud to catch a few, several mating pairs were stunned for a bit, and then flew away. One detail I did catch was that the males have (white, almost see-through) feathered antennae similar to some Moths. This may help identify it better, but without a super close up view, identification will be impossible. For now, let’s just enjoy the sunset swarming.

Video was recorded on May 11, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4. For close-ups of a small insect, please check out this post featuringCarpet Beetles which received an update today with new pictures.

Dunning’s Miner Bee - Andrena dunningi

With a few days of sunshine and gentle winds, it’s finally beginning to feel like spring over here in Toronto. With springtime around, the flowers have opened, the greens are growing, and many prominent insects begin to make themselves known. Time for me to go outside! While tending to the front and back yards (and checking for dandelions), I was greeted by 2 distinct Beesflying around in search of flowers or mates: The Eastern Bumblebee and the Carpenter Bee. I’ll wager their numbers will pick up as they establish colonies and homes respectively, and come summer when many more flowers open, they’ll be out to forage for their families. While these are the largest Bees you might see, there are several smaller, solitary Bees that also emerge from an overwinter to build nests and search for food. The Dunning’s Miner is one such Bee. I haven’t seen any yet this year, but the last few years they have been spotted near flowers in my neighborhood. Or at the very least, a Bee very similar to it; Andrenidae (and genus Andrena) Bees can be tough to identify without looking at them very closely. Dunning’s Miner is well known and wide-ranged, so it’s the best chance we have to discuss this family of insects. The description below may sound similar to the Unequal Cellophane Bee’s description (different Bee family), but it’s worth it to share again.

These Andrenid Bees make their homes in soil and sand, digging a column with side chambers to store the next generation of Bees and the pollen that the mothers gather as provisions. Though a solitary species, they can nest close to one another if there’s enough room to go around. The Cellophane Bees apparently nest in larger aggregates and (as can be determined from even a pictures) are larger than Andrenids, which helps to identify them if you happen to find some Bees near holes in the ground. Strange, but true to know that Bees can live comfortably in the ground, as we usually expect Bees to live in tree hollows or wooden cavities. They do live there of course, but underground living is more common than you may expect (even Bumblebees live underground). Nevertheless, whether in the ground or a tree, the hardworking Bees get to work providing for their young while simultaneously pollinating the flowers they visit. Dunning’s Miner is reported to be a generalist; feeding and visiting on many flowers. While Bumblebees may have more longevity (due to their colony structure) for pollination, Miner Bees can help get things going for the first wave of spring flowers! Enjoy these Bees while you can as they bow out gracefully after June, although other Andrenid Bees keep to a different schedule. Keep that in mind, as timeframe will help you identify what visitors come to your garden. Bless the Bees! Especially the mother Bees!

Pictures were taken on May 3, 2020 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Varied Carpet Beetle - Anthrenus verbasci

I was looking through the insect orders and families that have been covered here and was surprised to find that I haven’t covered these little guys. As it turns out, I don’t have too many pictures of them either which makes me sad. I’ll have to come back and add more Beetles to this post as I take more pictures! Though fairly small, the checkered pattern on their back makes the adults easy to spot, but you’d need a powerful magnifier to see the fine details such as the position of their eyes and their tiny antennae. I’m not sure how common they are in other parts of Canada or North America, but at home there’s always a few individuals that are found yearly, crawling around just before and after the winter. The ones that emerge in time for spring get to enjoy the outdoors while those that emerge before winter will need to remain indoors if they wish to roam around. They’ve obtained a bit of a status as a pest, as the household environment can provide these Beetles and their future larvae with nourishment (more so the latter, adults (like the individual in Picture 1) prefer to feed on pollen). As that wonderful name “Carpet Beetle” suggests, these Beetles may have a taste for human furnishings, which can make them pests.

Don’t let these images undersell just how small the adults truly are! They are much smaller than any other Beetles shown here, including the Yucca Beetle! Like the Yucca Beetle, a few may be adorable, but an aggregation of them may present issues. To clarify, these Dermestidaefamily Beetles may occasionally eat some furnishings because the hungry larvae need a diet of protein to grow. In nature, their protein sources come from dried fur, fallen hairs, shed skin, dandruff, wool, silk; anything organic in nature really. As such, when the larvae are abundant in a household, they may turn their attention to materials that fit this description such as clothing, loose fabric, and yes, carpets! They’ll need a source of water too. Best thing you can do if you find them is to vacuum them up, but unless there are many little larvae wriggling around, you may not find them. If you suspect you have any, look for millimetric grubs coated in small hairs. They’re quite small, so small in fact that the adults may use bird’s nests as locations to lay eggs. Just like in the Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers film, “The closer we are to danger, the further we are from harm”…”you are very small”. Considering the visual acuity of birds, its a risky proposition, laying eggs next to a predator, but these Beetles seems to make it work.

Update:7 more pictures added on Friday May 13, 2022. Hopefully this better conveys the size of these little beans. While they do seem tick-like, they do not bite. You can even see the little wings poking out.

Pictures were taken on April 22, 2019 with a Samsung Galaxy S4 and May 18, 2021 with a Google Pixel 4. Update pictures were taken on May 12, 2022.

Post link

Black Dancer Caddisfly - Mystacides sepulchralis

The year 2021 was a great year for finding and observing Caddisflies in their natural environment: on the vegetation by nearby streams. Since they’ve pupated, grown their tent-shaped wings and left the flowing water, they aren’t likely to return for a swim anytime soon, and yet they always seem to want to stay nearby. The only time they may actively revisit the water (up close) is to lay eggs. I’m not quite sure what this specie does since there’s not very much information to draw from, but the consensus seems to be that most species don’t lay eggs directly in water. Instead, they are laid in large number on nearby aquatic plants, sometimes coated in a viscous clump of gel. I’ll be looking around the water’s edge this summer for specks or jelly if I find any adults in the area. While I’ve implied that most lay eggs of vegetation, there are reports of some brave Caddisflies diving in to place their eggs! It would save a bit of time and may even be safer for the young larvae, as the ones on the leaves have a bit of exposure to predators and risk of desiccation until they drop into the stream to begin their lives. Gotta gather those stones!

While I’m not sure at all on the egg-laying habits (or dietary habits for that matter) for this specie, I can certainly be sure on the identity of this particular Trichopteran. The Black Dancer Caddisfly has elongated mouthparts (which resemble thick antennae or claws)and a thin, long, whip-like antennae with a ringed pattern along the first few segments. No camera flash was using to grab these pictures, so those red eyes aren’t a consequence of camera light. The eyes can be another trick to help identify these elusive creatures. I’ve read that only the males have bright red eyes, but I couldn’t say for certain. I’d need to do more research, and they only other way to tell for sure would be to examine a specimen with a dissection microscope (which I don’t have). If you do come across an insect that looks like this, monitor it closely, and if you do, document what plants or flowers it prefers to visit. Flowers in particular would be helpful to learn if it actually has a liquid diet or doesn’t feed. With luck, it would be some nearby flowers close to the stream. Depending on the flowers they prefer, those palps might be useful grasp on other structures while feeding or to pull flowers closer to its mouth since Trichopterans lack a proboscis. More info would go a long way here. If a revision to the Audubon Insect Guide comes out, this specie would be a great inclusion for the field guide. Especially since there aren’t many Trichopterans in the guide as is. They’ve been compiled together with similar looking insects (though different orders) such as Lacewings, Alderflies and Stoneflies. The Black Alderfly does have a resemblance to it, but you can tell by looking at wings just how different they are.

Pictures were taken June 16, 2021 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Cluster Fly - Pollenia spp.

When I first uploaded this drab looking specie of Fly to the blog last year, I had only found one on the leaves. With a name like “Cluster Fly”, you would expect many individuals grouping closely together and hanging around to enjoy the warmth of a new spring. While I can honestly say that the Flies I found weren’t exactly super close to each other, the warm afternoon weather caused many individuals to come outside and swarm around. It was hard to get a moment’s peace outside with Fly after Fly landing on me or nearby and needing to be shooed away. It wasn’t quite a cloud, but there could’ve been at least 20 Flies nearby, and maybe more if some flew away and others took their place! If this is what they’re like outside, just imagine what happens when they hide away in confined spaces during the winter such as inside houses! Have no worries because as pesky as Cluster Flies sound, they only enter houses to escape the cold. When winter arrives, they enter diapause and await the end of winter to become active again: with their metabolism slowed down, they won’t breed. Even if they wanted to breed indoors, Clusters Flies seem to rely on parasitizing earthworms with their eggs. Maybe if have any potted indoor plants you might want to check the soil if you’ve seen adult Flies near them.

A bigger problem that’s been reported with Cluster Flies is if they were to die indoors they may draw other predators indoors in search of an easy meal. Before searching your homes (inside and out) for a potential cluster invasion, remember that there are always signs you can watch for and ultimately they aren’t as big a pest as other types of Flies. They don’t tend to spread filth (beyond any germs in soil) and they feed on pollen from flowers rather than rotting material or garbage. I’d still recommend you wash your hands after handling them, and speaking of handling them, this is the first time I’ve ever stuck a finger out to a Fly and it actively climbed aboard. These insects aren’t skittish and react much slower compared to BlowfliesorHoverflies. While this makes me appreciative for the closer look at them, I do fear for their safety if they are sluggish aren’t predators. Perhaps the summer broods have more speed to spare, but if there is evidence to support that, I have yet to see it. If I find any answers, I’ll create a follow-up post, but these Flies tend to be overshadowed during the summer by the other flower-loving Fly species.

Pictures were taken on April 11, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Two-Spotted Grass Bug - Stenotus binotatus

A green area filled with green grass, green leaves, and a certain green insect skitting around in this green world. With a bright green body, this specimen could have a much easier time hiding in your garden or the meadows that it calls home. You’d probably be better off searching for it in the meadow as there’s plenty of tall grasses for it to stick its rostrum into and enjoy. Yes, the Two-Spotted Grass Bug does in fact feed on grasses, but not the blades of grass that are seemingly more appetizing. Leaving the blades for the Grasshoppers to munch, this verdant Plant Bug uses its mouthparts to take nutrients from the clustering flowers of grass. As well, it isn’t too picky about the grass flowers it chooses to feed on whether a nymph or a full grown adult (like this specimen). The major difference is how to get to and from the food it needs since the nymphs lack wings. While known for feeding on grasses, they don’t seem to be generalists as they’ve been found feed on tree flowers too. With zebra grass growing in our neighborhood, I wonder if they have taken to that?

While named after the spots on their thorax plate, you could be forgiven for missing them by looking at the stripes that run down their wings. They certainly are lovely, but you have to look for those spot markings too. With look-a-like insect such as the Alfalfa Plant Bugand Ilnacora malina,it’s helpful to be sure which insects are flying around the meadow. With respect to the latter which is a dark green with a darker head, the Two-Spotted Grass Bug tends to be a paler green color with green on the top of its head. Although sometimes you may find a yellow-colored Grass Bug! What’s this! It seems that male S. binotatus tend to fall more on the yellow side while females tend to have that pale green color! Also, while I’m not totally sure, it seems that males have more their spots become gradually more prominent as they age, practically connecting with the markings on their back into one long line. I’ll need to find and review more specimens to be sure, and find more in person too! As with every insect I photograph, if I can find more, you’ll find them here, and I do sincerely hope that you enjoy them!

Pictures were taken on June 16, 2021 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Dog-Day Cicada - Neotibicen canicularis

Well, I hinted at this in a very important earlier post that honors someone who will always be with us, and here it finally is! Insects are very resourceful when it comes to entering adulthood, even if it means using manmade structures to get the job done. It may be topical to share this on Earth Day (with an insect that spend most of its life in the earth) and take a small, unconventional glance on how insects and humans interact and share the planet. I agree that other avenues such as climate change, habitat destruction, biodiversity changes and examining more significant insects (Beetles,Butterflies&Honeybees) are far more relevant, but I’d like to share the short encounter with a Cicada molting using a car tire. It’s an unexpected example of the natural world using human creations. I’ve seen Cicadas using wooden benches and concrete barriers too, but at least those are similar to trees and stones. Tires are something completely foreign, but it does offer a good grip for the nymph’s old shell to grab and hold on as it molts. This nymph must have been extremely determined to climb up the curved slope of the tire’s bottom and climb against gravity! Amazing as this new molting post is, I don’t think Cicadas would make it a yearlong habit when aforementioned natural structures are available.

Talking about nature, insects are some of the best environmental caretakers we have, and it would benefit us to learn a little more about them and realize how different insects contribute to the ecosystem and food webs. Not to mention, appreciating the contributions of every insect order, rather than just writing them all off as pests. Insects help us in more ways than we can imagine, but the wrong insect in the wrong place (e.g. an invasive specie) can be just as detrimental so we must be respectful and careful with our interaction with them. Their lives deserve all the beauty and triumph that our lives do, and that might mean a little help for them. Even caring for trees and wildflowers, cleaning up where we can and being careful with biological debris such as leaf litter and fallen logs. Nothing too intrusive unless something needs a major correction. Just a subtle, guiding hand. With this Cicada friend, I just found the adult insect stretching its wings and hardening its body, missing the molt process. It was relatively fresh as while the wings were almost ready, the body’ still needed more time to darken. I didn’t know how long the Cicada friend would hang around for, but I didn’t want to leave it alone, so I picked it up and placed it on a nearby tree. Perhaps it’s for naught, but at least that Cicada won’t have all that effort ruined by being run over. After it began to move around and climb upwards, I continued with my walk. Hopefully that Cicada enjoyed a wonderful summer!

Pictures were taken on August 18, 2021 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Brown Marmorated Stink Bug - Halyomorpha halys

So I’m working at my desk, doing research for an online course and I hear a noise. It sounds like a low buzzing, and it also sounds much larger than an Asian Ladybug, a more common visitor in my warm when spring’s warmth arrives. I turn around, that there’s a large flying body zooming around the lights and flying around the room with great haste! I thought it might be a Western Conifer Seed Bug since they’ve appeared in my room before, but it was flying too quickly to be sure. Couldn’t tell until it finally settled down, but there’s something about insects and light, and it keep circling the lamps. By this point, I had closed the door to prevent escape into the house. After a few minutes of flying around and tension growing, it crashed behind a set of drawers. Searching for it, I found the visitor on my tennis racquet, upon which I got a good look at it. A Stink Bug has awoken up for the spring! When I went to get my phone, the little Bugger took flight and began to buzz around the room again! Argh!! At least we know what it is now.

While it has a compact, shield-shaped body, it can be startling to see the full length of the wings for that split second before flight. When at rest, Stink Bug wings are folded against the abdomen, the forewings conceal the hindwings until it’s time to fly. It just wouldn’t be possible to maneuver that wide body without powerful wings, so when it’s time to go, the wings unfold out and get flapping. Getting back to the story, it resumed flying around the room aimlessly, eventually crash landing on top of the drawers this time. No slowing down, just crashing to an abrupt stop! Thank goodness an insect’s armored body allows for that, even if it may be too much for some other body parts to handle. Poor thing was missing a leg and an antenna. It could be tough to fly without all your instruments working. I picked it up in a glass and put it out the window (and without any spraying of stink) so that it wouldn’t be a bother indoors. Just a little story for today. Try not to be too nervous about the insects that decide to spend the winter in a warm house. They don’t mean to be bothersome, but they just can’t stand the cold. Quite relatable!

Pictures were taken on April 12, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

Pavement Ants - Tetramorium immigrans

Here we have the first video of the year, and wouldn’t you know it the Pavement Ants have gotten to work and are setting up their new colonies and territorial ranges for the year. Once again, a turf war (that extends fairly far out) is fought on the patio in hopes of maintaining a good spot for the colony to proliferate and enjoy the warm weather. The patio provides ample protection and environment thanks to the stones, lack of plants (except for mosses and small grasses) and the insects that traverse it, so no wonder it’s sought after! After the fighting ends and the territories are established, it returns to business as usual for the Ant colonies: foraging, exploring, defending, and ventilating the nest in the summer. The numbers of workers will soon shoot up again thanks to the diligent queen of the nest (and in some cases, 2 queens working together). The unusual thing to note is that despite the fighting and the massive Ant casualties as a result, in a matter of hours all traces of the battle will be gone! The next time I showcase a video of a colony conflict, I’ll make it a time lapse for as long as possible to see what happens when the dust settles and retreat is called.

Video was recorded on April 13, 2022 with a Google Pixel 4.

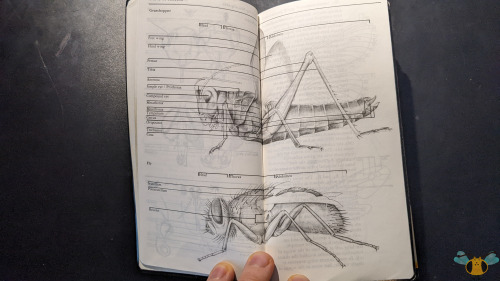

Short-Winged Meadow Katydid - Conocephalus brevipennis

With my field guides and my main literature resource explored, this blog returns to the showcase of many beautiful and wonderful insects of Ontario (and beyond)! This insect is actually one of the few insects that isn’t included in the current Audubon field guide, so lets revisit it today. True to her name, she has shortened wings across her back. This is how they’re commonly seen, but you might be able to find one with elongated wings if you’re lucky! With a blade on her abdomen, she’s definitely a female specimen. She was observed crawling on a goldenrod stem that’s gently drooping down due to the weight of the Katydid (and maybe the snail hiding underneath the leaves?). Looks like she was searching among the flowers for a tasty snack. While the flowers didn’t get more than a nibble, there are pieces of leaf in between her mandibles in some images, and in some other images are her legs which she cleans every so often as she travels. It’s amazing just how simple yet sophisticated an Orthopteran’s mouthparts are: delicate enough to clean without scraping the legs, but powerful enough to tear plants and soft-bodied insects for nourishment. The mandibles are the prominent insect mouthpart given that they do most of the chewing, but let’s highlight some other important mouthparts.

Let’s get started with insect lips (really). They aren’t lips as we know them, but they act as supports to keep any food in their grasp contained while they shovel it in. They are known as the labrum (front lip) and the labium(back lip), acting more like plates and graspers. With the food stable, flexible structures that hang down from mouth called palps,and set of secondary jaws calledmaxilla(maxillae plural). The latter are used to orient the food around while its being chewed. They come in handy for pushing food into the mandibles and navigating a captured insect in search of a soft spot (this Katydid may not appreciate the later since they tend to be opportunistic rather than hunters). The palps on the other hand are used to sense, assess and “taste” the food. They don’t necessary function as primary tongues, but they are essential for the insect to interpret the world around it. The Larger palps in the front are called maxillary palps while a set of smaller palps on the back lip are called (you guessed it) labial palps. All these parts work together harmoniously to keep this Katydid well fed as she explores the forest, while carnivorous insects would use these same mouthparts as powerful weapons to hunt. They certainly are effective either way, but there are other alterations to those mouthparts that help other insects thrive. Mosquitoes for example, they don’t use mandibles to tear up food. What other insects can you think of? Check the guides if you need to.

Pictures were taken on September 11, 2021 in Kleinburg with a Google Pixel 4.

Post link

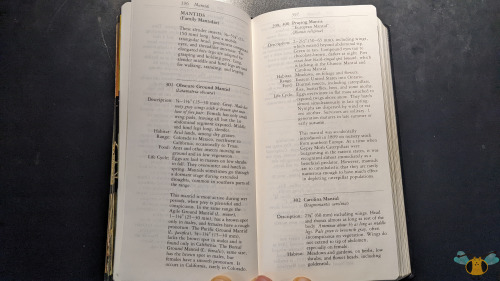

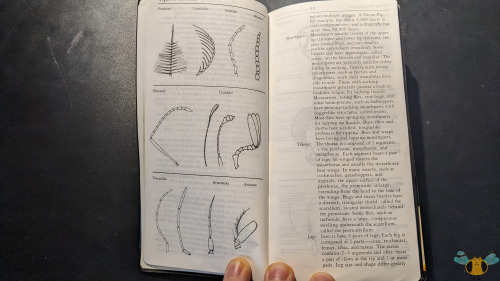

Daly and Doyen’s Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity 3rd Edition, James Whitfield and Alexander Purcell III

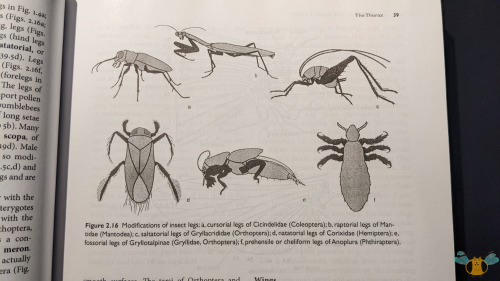

One more little bit of literature to share, and then next week I’ll return to the regular scheduling of sharing insect photos. Yeah, wasn’t really planning for this type of showcase, but it’s worth it to show you (dear reader) what helps me identify insects. This is my textbook from my time at the University of Toronto. Though pricey, it was handy during my time in Insect Biology and was a great asset to getting my bug box ready for the end of the term. Unlike the previous 2 guidebooks, this one is far more technical when it comes to insect identification. This is definitely for the best since identification of tiny organisms requires examination of the tiniest of details. You’d need a dissection microscope to get your money’s worth, more on that later. For now, the knowledge in this book is wonderful. While most of the book is in black and white, colored pictures (like 5 and 6) are used to highlight the fundamentals of the insect world without becoming too technical. It is a textbook after, so you can expected detailed outlines of insects, their systems, their ways of life, habits, locomotion, ecosystem roles and everything in between. The diagrams on Pictures 2-4 are some examples. The insect education is thorough and easy to understand, but when it comes to insect identification, this textbook is extremely thorough. Follow along using Pictures 8 and 9 as examples.

By thoroughly examining a specimen up close and knowing what to look for, an insect can be sorted and classified all the way down the genus, if not the specie if you’re sure. The guide explains exactly what to look for to confirm. You start from the very top of the order and work your way down as your become more familiar with your insect, eventually discovering what it is. The guide outlines what details or structures to focus on, and rules out other insects based on your findings. Now, it’s not completely bulletproof as insects do have variability and there can be wiggle room for interpretation, especially when multiple people are looking at one microscope. One story I have was when I was examining a Bee and trying to determine its family. Since its face was coated in hairs, I couldn’t see the lines on its face. After “shaving” the Bee with an insect pin (not the point), the lines were visible but even with 4+ people looking at the specimen, still no avail. In the end, my professor settled on Andrenidae Bee as the family and wouldn’t mark me down for it. Mining Bees can certainly be a challenge, which is to say nothing of smaller insects. Perhaps we can count that as an anomaly since the organization schema worked perfectly for everything else.

Do I recommend you get this textbook however? Maybe. It’s a little big and technical to bring outside on bug hunts, so the Audubon Guides would do otherwise. If you like insects and would appreciate a comprehensive education tour de force on them, plus technical look at them that doesn’t go into a more research-heavy focus, sure! But it is introductory material (and that can only get you so far). As well, there is a new edition available now (from 2021) so that may be worth checking out instead. For me though, I’m happy with this textbook and am glad to have it as a resource for this blog. Either way, I’d never part with it either as it’s been autographed by one of my most dear friends. You can check out her blog here. She’s just gotten her Doctorate, and I’m so proud of her!

Ally, this post is for you. Thank you!

Post link

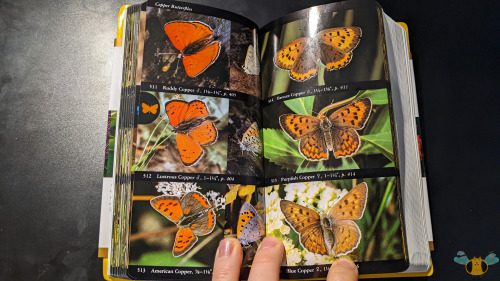

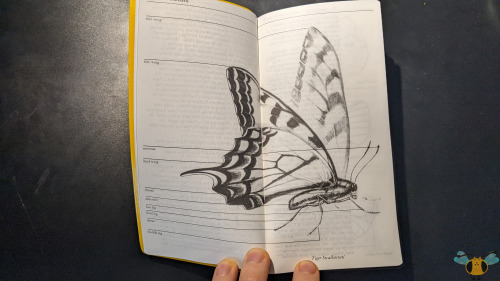

National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects and Spiders, by Lorus Milne and Margery Milne

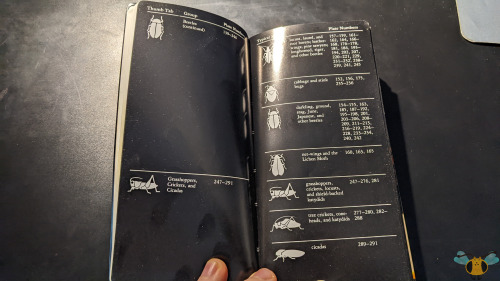

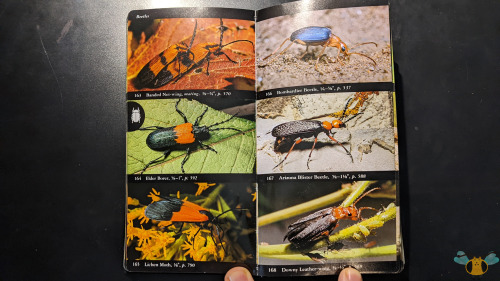

With a new primary identification resource (the NAS Butterfly Field Guide) explained last week, it seems right to also share the field guide that I’ve relied on for many years for insect identification. It’s always with me when I go looking for insects and it’s always my starting point when looking to identify a new insect from a photo. Plus, it’s good for a read if your curiosity on an insect or insect family is piqued. It’s organized beautifully and is nearly 1000 pages of insect goodness! Towards the end, the guide contains a few pages on arachnids too. Notably spiders, but it also mentions some small creatures and scorpion-like creatures too. We’re all about insects here though. Like the Butterfly Field Guide, this book focuses on North American insects (and it can’t cover all of them) and describes them in detail using the photography and detailed descriptions within the text section. For example, underneath the pictures of the Mantids (Picture 6), it directs the reader to pages 396-398 which briefly describes a few species with their behaviors, ranges, diets and even their life cycle! If you look closely at the photography sections from the book, you may notice something strange is afoot: some of the insects in the section aren’t like the others.

The field guide includes some insect mimics within the section of the insects that they mimic. For instance the Mantidfly (a Neuropteran) hidden among the Mantids. What others can you find? I like the insect orders organized, but I can appreciate that those just beginning to learn about insects may appreciate the grouping. Also included in the guide are illustrations and diagrams on the bodies of the many different insect orders. Special attention is also called to their heads, mouthparts, wings, antennae, legs and other notable features. It’s a handy glossary if you need to know the difference between a tarsus and a trochanter (parts of the leg). Handy is probably the best word describe it, though as much as I love the book, I do feel it may need a revision soon. Not quite an overhaul, but lots of small additions here and there would begin to add up. The world of insects is in constant research and examination, and with that many changes are born and the field guide should reflect this. For example: some of the scientific names have changed, new observations are discovered, the former Isoptera order (termites) is now folded into the order Blattodea (Roaches), more insects could be added to the pages (the Black-Legged Meadow Katydid is a noticeable missing insect to me), True Bugs could be reorganized.

Just suggestions, but I’d look forward to anything that follows. Until that day, I very much recommend this field guide and will continue to carry it with me when I go exploring. For more information, check the guidebooks directly at the NAS webpage.

Post link

National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Butterflies, by Robert Michael Pyle

It may be April Fool’s Day today, but I assure you this is no joke. I’m happy to announce that I’ll be using another field guide to help with insect identification. Previously I only had the Insect and Spiders Guide (also the Rocks & Minerals and Reptiles & Amphibians guides), but this book just arrived today. I’ll be looking through it in depth, but having just briefly looked through its contents, it’ll be a big help. For those not familiar with Audubon Society Field Guides, the books are structured to make identification relatively easy. The Butterflies are sorted into their family groups, each section accompanied by a silhouette of a typical specimen. In each section are wonderful photographs of Butterflies out in the field (some have 2 pictures since the top and bottom of the wing can feature different colors or patterns), their common name and a page number. The page number is used to locate the description of the insect in the back of the guide. For example: In Picture 6 the Desert Swallowtail says, p. 329. Scrolling to that page you can find pointers identification, range, behaviors and other facts. Since the guidebook it covers all of North America, there’s bound to be a few species I’ll never see (and even a few species not in the book), but it’ll be fun to learn about them nonetheless. I’m looking forward to using this book in between insect hunts to figure out the identities of some more peculiar Lepidopterans!

Since this is a Butterfly guide, there are no pictures of Moths, but there are descriptions of Caterpillars,Chrysalids and eggs. And since Skippers are Butterflies, you’ll find them here too. Me personally, I’d like to see an Audubon guide to North American Beetles given the sheer variety of Beetles out there. For more information, check the guidebooks directly at the NAS webpage.

Post link