#kozure ookami

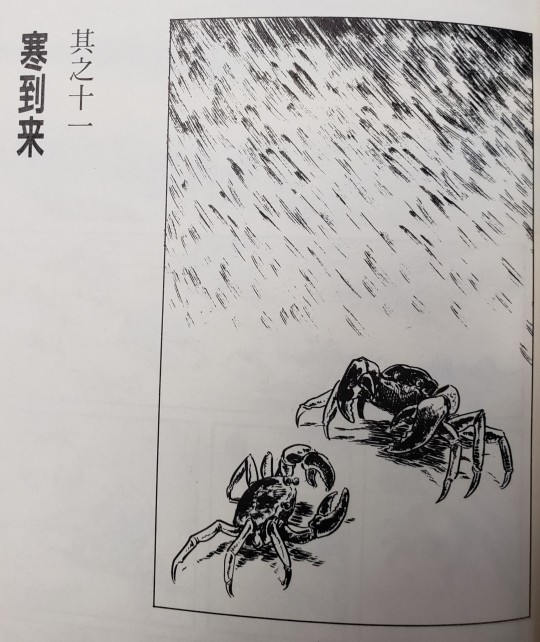

Chapter 11, The Arrival of the Cold. 寒到来 (kantourai).

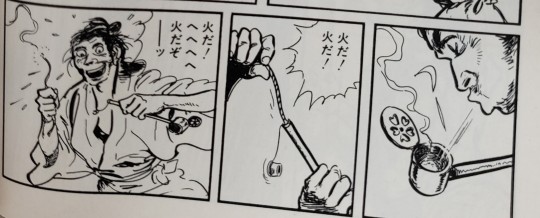

So, “aka neko” (Red Cat) appears to refer to this guy, an arson. So I guess “red” was not health or blood, but fire (火, hi).

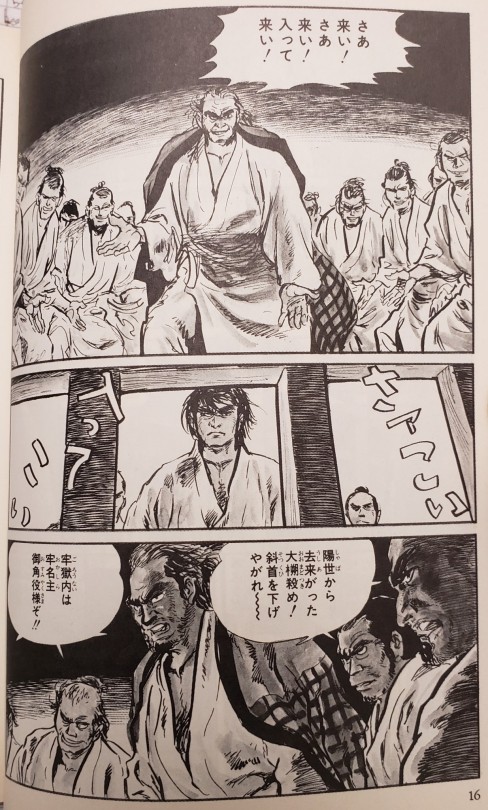

So the convicts in the jail are indeed singing a welcome song for Ogami Itto! “Saa, koi” and such all amounts to “So come, come on in!” The guy at the bottom adds a bunch of stuff about leaving the world behind…

This series was written a good 20 years before Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, but somehow I can’t help but think of “Be Our Guest” here, Edo-era prison style.

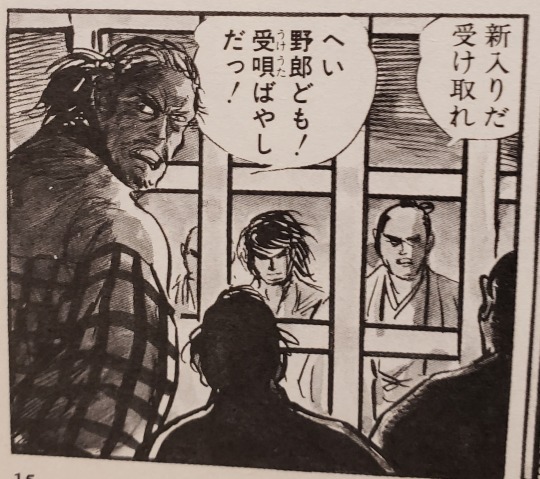

Ogami Itto is being thrown into prison. The guy on the left says “Hey guys, it’s time to do the welcome song!”

Whu….?

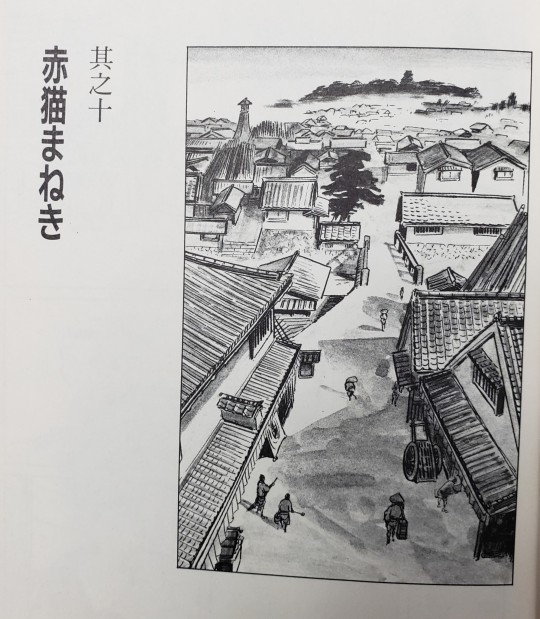

Kozure Ookami (Lone Wolf and Cub) Chapter 10: 赤猫まねき (akaneko maneki), Red Cat Invitation. Interestingly, the English translation goes with just “Red Cat.” People might be familiar with the “maneki neko,” the beckoning cat – usually a ceramic or status of a cat sitting on its hind legs and with a front paw (or both front paws) raised in beckoning. Usually maneki comes before neko, so I’m not sure of the significance here of it coming after. Also, red maneki cats usually symbolize good health, but red can also symbolize blood….

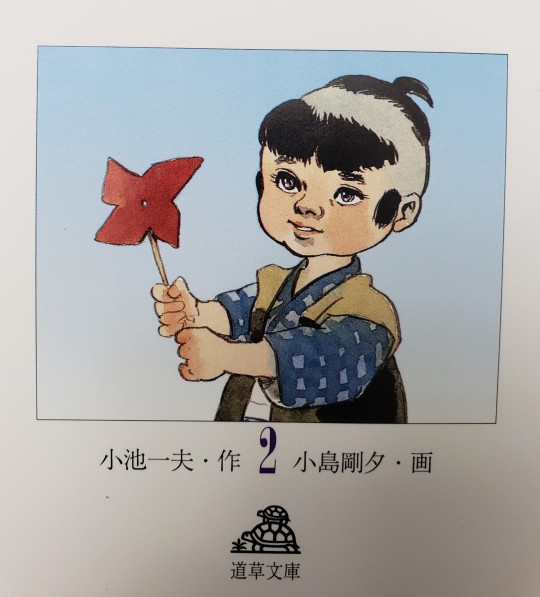

On to Volume 2 of Kozure Ookami (子連れ狼), Lone Wolf and Cub, featuring Daigoro with a かざぐるま (kazaguruma, a pinwheel).

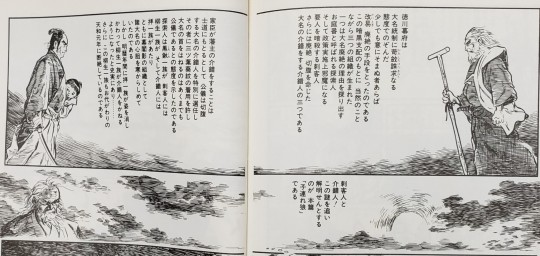

And here we finally get the full exposition for the story (well, most of it, anyway). The prose describes the Tokugawa reign, and the power of 3 groups. The Oniwaban (御庭番, or the garden one; basically ninja; of the Kurokawa clan), the assassins (刺客, shikaku; of the Yagyuu clan), and the executioners (介錯, kaishaku; of the Ogami clan). And that historicall, the Ogami clan mysteriously vanishes, with Yagyuu taking on both roles. And then eventually Yagyuu vanishes.

And that this story could be one of the possible answers!

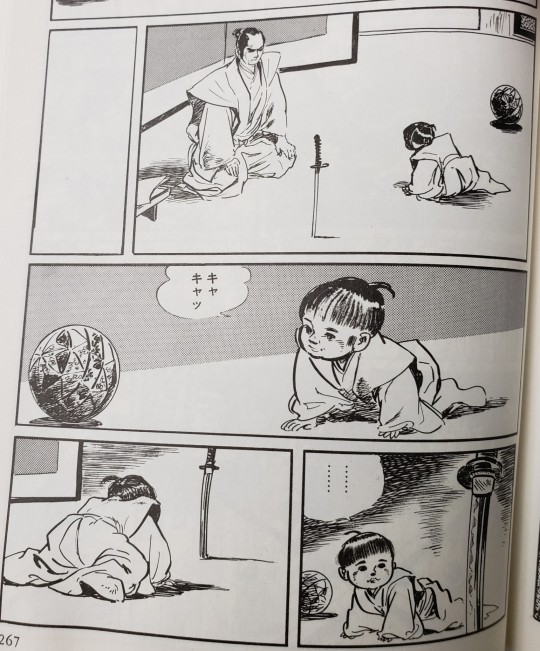

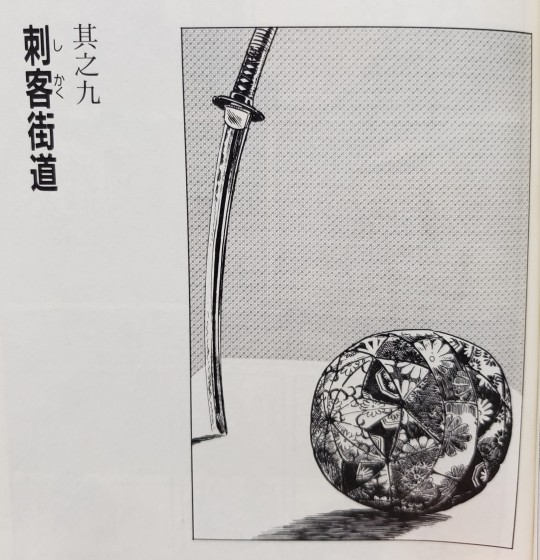

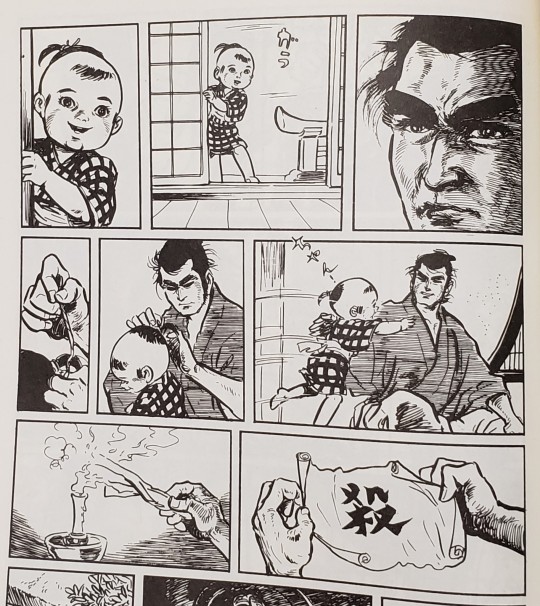

Yes, Chapter 9 is showing us a lot about Ogami Itto’s past. Here, we see that he gave a very young Daigoro the chance to choose whether he would join his father (choosing the blade), or he would join his dead mother (choosing the temari, or 手毬) – meaning that Itto would slay his son.

Kozure Ookami (Long Wolf and Cub) Chapter 9, the final chapter of Book 1, is 刺客街道 (shikaku kaidou, assassin’s road). Flipping ahead, it appears the chapter is mostly a flashback, and we’ll finally see some of Ogami Itto’s past.

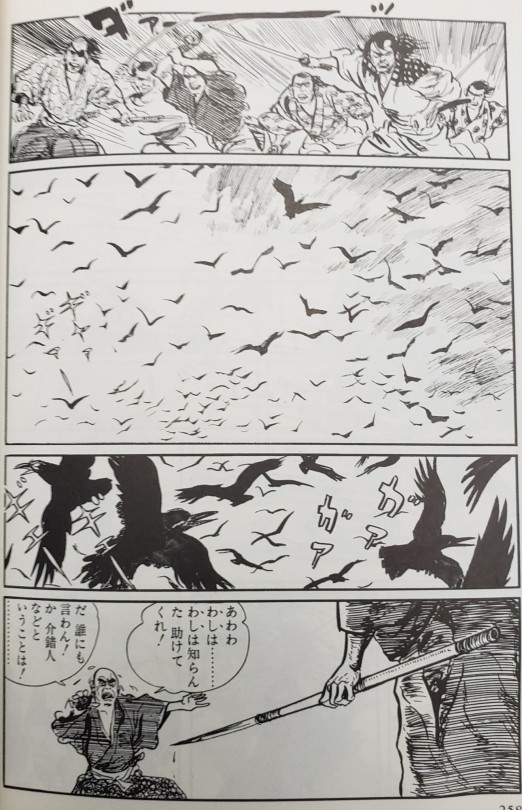

Two things about the end of Chapter 8. First, notice the six “tobiccho” (gang of ronin) at the top. Then notice the six uses of “ギャア” and “ガア” (basically, screams). The English translation made the first two “caww” for the crows, but it’s pretty clear they’re all the death cries of the six tobiccho, perhaps mixed in with the birds (the imagery of which is an echo of the Chapter title and subject matter, which includes the wings of birds).

Second, the leader of the tobiccho has realized who Ogami Itto really is. He begs for mercy and says he won’t tell anybody. Oddly, the English translation says “you’re the Shogun’s executioner.” But the Japanese translation only says “介錯人など” (kaishakujin nado, executioner and such). This is really the first glimpse we’ve gotten into who Itto might really be. It’s interesting that the English translation decided to reveal the shogunate connection earlier than what seems to be revealed here in the Japanese version.

At the beginning of the doubly-long Chapter 8, the head of the “tobiccho” (a gang of ronin that have banded together for general crimes and debauchery) meets Ogami Itto and says that he seems familiar. But he can’t quite place it.

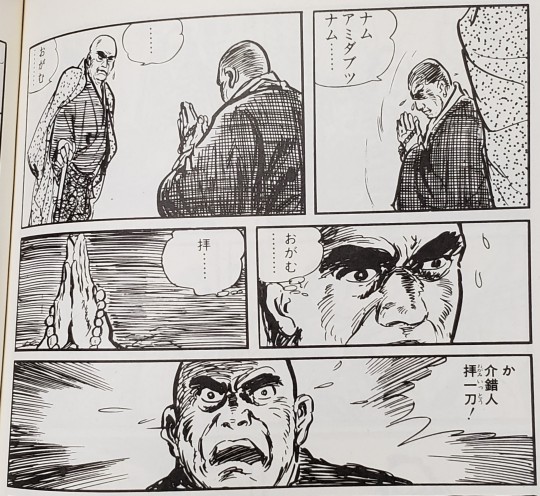

At the end of the chapter, the tobiccho are preparing to leave the hot springs, and they announce that they are going to kill the other visitors to keep them quiet. One of those visitors is a sick samurai. He begs for a 介錯 (kaishaku) while he commits 切腹 (seppuku), the ritual suicide. A kaishaku basically stands behind the person committing suicide, and cuts off their head at the moment of the stomach stabbing.

The word “kaishaku” shocks a memory for the head of the tobiccho. He then sees a monk, who is chanting the Namu Amida, which makes him think おがむ (ogamu), which means “to pray” or “to pray with hands pressed together” (it’s about the posture of the prayer)…. he repeats it… ogamu… ogami…. suddenly it all clicks with “介錯人拝一刀” (kaishakujin ogami itto) – or, Executioner Ogami Itto, and he realizes who the latest visitor really is….

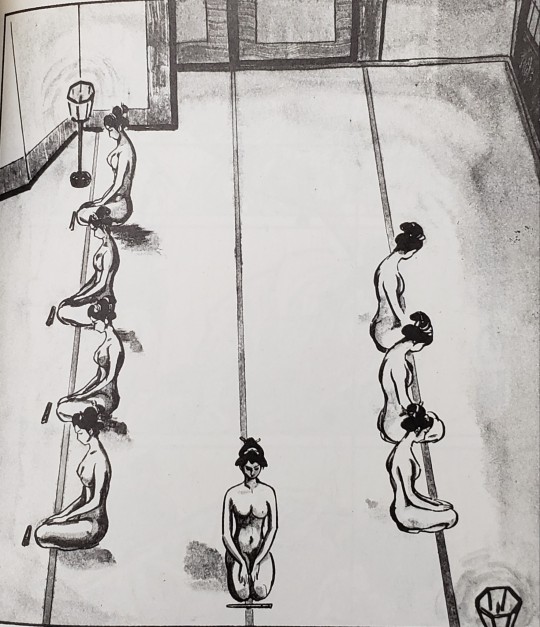

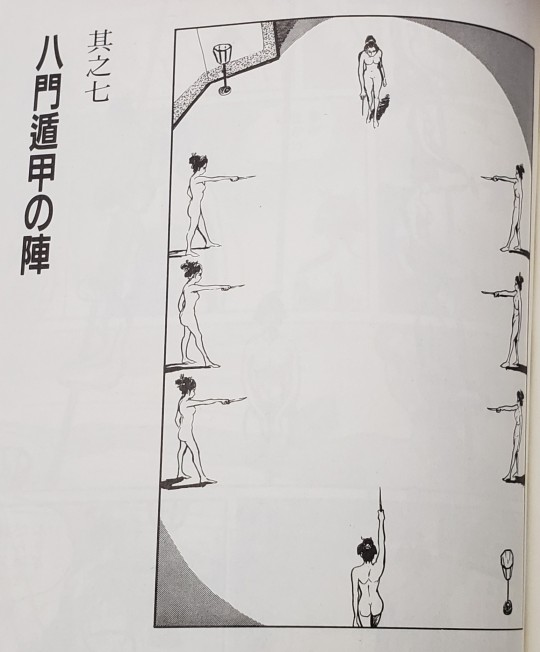

So each of these ladies has a kanji on her chest (either a tattoo or painted), 1 through 8. The first three, however, don’t use 一、二、三. Instead, they use 壱、弐、参. These are 大字 (dai ji), or alternate kanji.

As you might imagine, it might be easy to alter 一、二、三 (adding two lines to ichi to make san, etc) to falsify documents. So these more complex kanji, the daiji, are typically used in legal documents.

Alternate versions also exist for 十 with 拾, and 万 with 萬。

Ok, I’m certainly learning about a lot of new things as I read through Kozure Ookami. Chapter 7′s title is 八門遁甲の陣 (hachimon tonkou no jin), which roughly means something like The Mystical Eight Door Battle Formation.

The English translation for Lone Wolf calls this chapter Eight Gates of Deceit.

So what’s the deal?

遁甲 (tonkou) refers to a type of Eastern astrology. In particular, there’s something called Qimen Dunjia, which in Chinese is usually spelled 寄門遁甲, which is an ancient form of divination from China. It was originally used with figuring out military tactics. It uses a 3x3 grid.

I’m not exactly sure where “bamen” (八門) comes into play. But either way, Japanese audiences are probably familiar enough with the term 遁甲 to understand the meaning here.

Western readers are probably much less familiar with the terms, and so they’ve chosen a different tact in translation. As far as I can tell, nothing in this title suggests “deceit,” and so the English translators are probably using something that happens in the chapter.

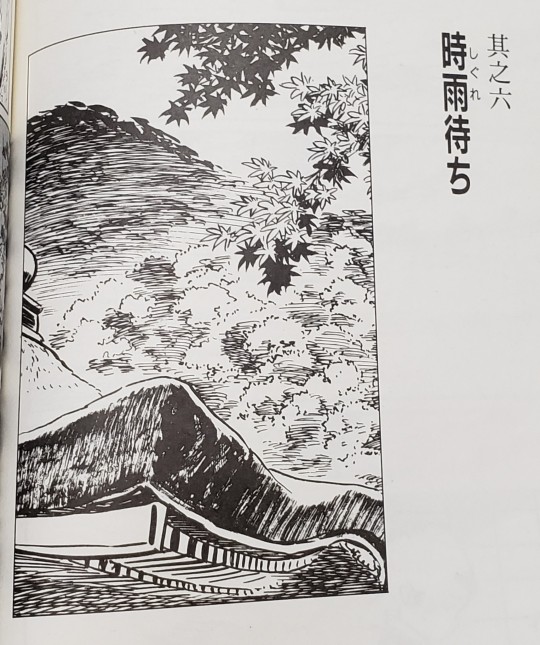

Another common seasonal word in Japanese: 紅葉, momiji. Momiji refers to the maple leaf, but it also means leaves turning red, or autumnal colors (the characters themselves mean ‘red’ and ‘leaf’). And again, ‘momiji’ is a special reading for these characters.

Chapter Six opens with an unknown man leading a horse, upon which Daigoro sits, singing a song. The man makes a comment about being told to deliver the boy to this temple, and he departs. Daigoro finds his father, upon which he reveals that the tie for Daigoro’s hair contains a message (殺, kill).

Daigoro has been involved in some important way in each chapter so far, and all quite different ways. I was not expecting this level of involvement, and it’s neat to see.

Chapter Six. “Waiting for the Late Autumn Rains.”

Japanese seems to have special words for seasonal weather. This chapter shows a good example, 時雨 (しぐれ, shigure), means later autumn or early winter drizzle. Which is also a special reading for those characters.

I think the first time I ran across the term “shigure,” it had to do with a museum in Japan that somebody (recently retired?) from Nintendo had created, and I think they were using the Nintendo DS (the original DS, which was just new at the time) to serve as a tour guide.

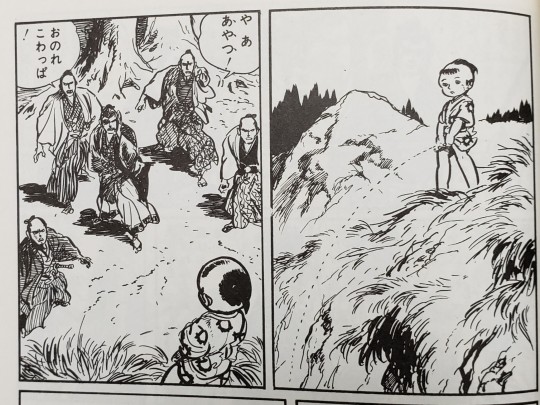

Well, this is certainly a way to start a chapter.

こわっぱ (小童, kowappa) is a derogatory term for a child, kinda like brat.

This is the second time in the first 5 chapters that Daigoro peeing has played a role in the story.

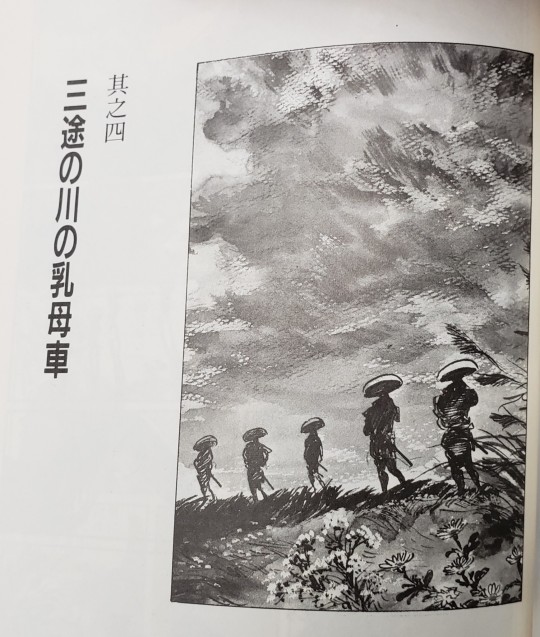

The 4th Chapter (其之四, sono yon) means something like “Baby carriage on the River Styx.”

三途の川 (Sanzu no kawa, Sanzu River) is, according to my dictionary “the Buddhist equivalent of the River Styx,” or the River of the Dead, for those not familiar with Greek Mythology.

乳母車 (ubaguruma, baby carriage) is “nursing mother” plus “cart.”

If this were another series, I might wonder whether they chose to mention the River of Death specifically in Chapter 4, since 四, four, can have the same pronunciation as 死, death. But so far, it seems as though every chapter is going to have death as a theme…

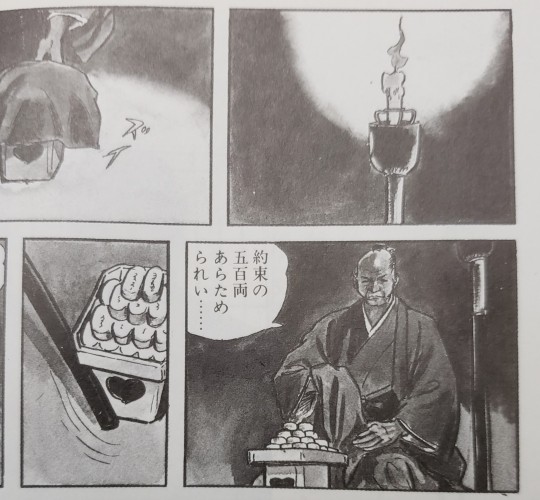

And even in the first word speech bubble, I learn something.

両 (ryou) are the coins piled on that small altar. As the man says, the “promised 500 ryou.” I was more familiar with the term “koban,” the oval gold coins (if you know what Meowth are, those are koban on their foreheads). Koban were apparently minted to have about 1 ryou of gold. So koban was the coin itself, but the ryou was the value of the material.

Like any currency, the value fluctuated over time. It looks like 1 ryou ranged around 1-4 koku a rice, where 1 koku of rice is considered the amount of rice to feed 1 person for 1 year. Other figures put 1 ryou ranging from $30 to $1,000 USD. No matter how you count it, 500 ryou is a hefty sum.

I’d be curious if anybody knows if the altar with the heart-shaped hole has any cultural significance? I imagine this series will have lots of importance cultural references.

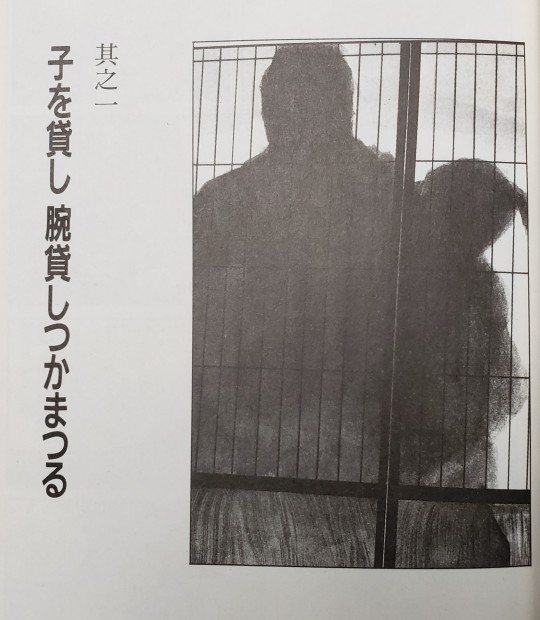

I was afraid of this…. I haven’t event started reading the first chapter, and I’ve run into something archaic. The chapters all have 其之 in front of them (其之一、其之二, etc). Apparently these are the kanji for その (sono), just nobody uses them much any more, they have an archaic feeling (appropriate for this story, then). Also, その gets used as counters for stories, episodes, or chapters, so 其之一 (sono ichi) amounts to Chapter 1 or Episode 1. I think I might have learned this a long time ago, but it comes up so infrequently…

And apparently, つかまつる (tsukamatsuru) is an old/polite form of 仕える (tsukaeru), to serve, to work. So the chapter title is roughly, Child for hire, “arm” (sword) for hire.

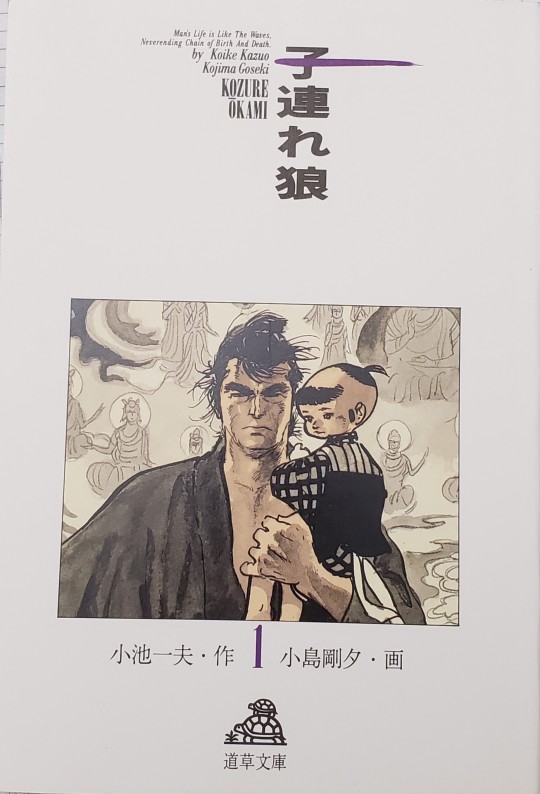

On to the next series! Next up, Kozure Ookami (子連れ狼). Numerous people have recommended it to me, and so I’ve wanted to read this one for a while, but I don’t know anything about it, other than it’s a historical play ( 時代劇, jidai geki).

It most often gets the translation “Lone Wolf and Cub” but as usual, the English is adding more than is in the Japanese. A more accurate translation would be “Wolf Taking along (his) Child.” The 連れ (tsure) means to take along, and becomes ‘zure’ when combined with 子 (ko, child), to give ‘kozure.’

This story came out in the 1970s (1970-1976) and comprises 28 volumes. It also looks like it will be heavy on historical aspects, so I’ll likely be on this one for a while. Even finishing one book per week will mean half a year!

Edit: Oof, and the first page is already pretty tough. I might need to intersperse something on the lighter side. Recommendations welcome!