#leslye headland

Russian doll put “I thought if I worked hard enough, if I kept putting the time in, if I kept my head down, you know, did everything right that this aching gnawing feeling of being an absolute failure would just go away” and “I look at you now, chasing down death at every corner and, sweetheart, where is that gorgeous piece of you pushing to be a part of this world” in back to back scenes

did they want me to cry

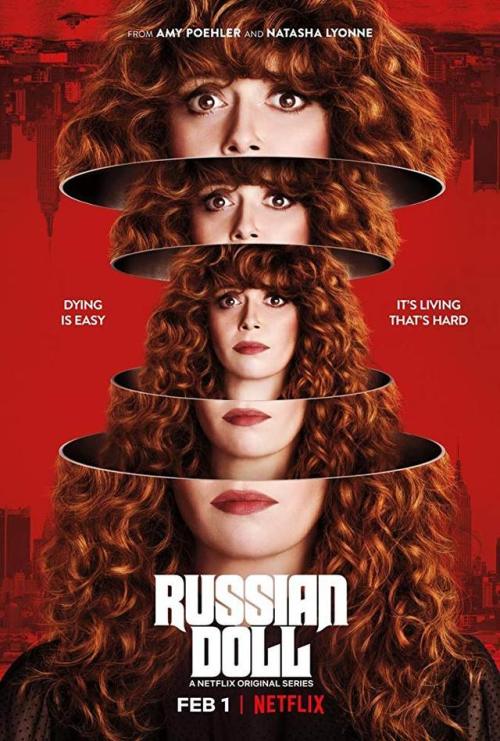

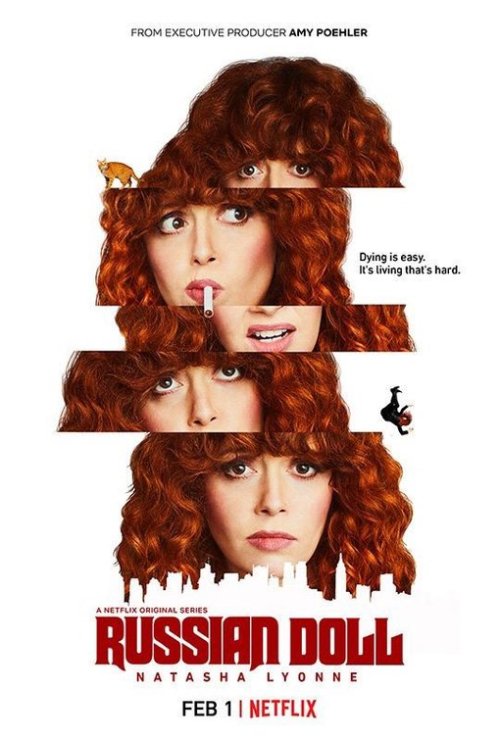

RUSSIAN DOLL

Russian Doll Season 2—not that great—is honestly a gift to me personally, as now I am always going to have the perfect talking point for my perpetual position: STRUCTURE ABOVE ALL (in storytelling)

This is going to be an excuse to finally write at any length about Russian Doll Season 1, one of my favorite pieces of television, but it’s going to be about 2 too, a remarkable instructional case that sets off in contrast so many of the things that make Season 1 a masterpiece of the medium. I actually understand better now what is so important to how Season 1 works, becauseof which elements Season 2 thought it could leave out, and it couldn’t! The post about making ratatouille.txt. Anyway there will be spoilers for the plots of both.

The main thing though, the most essential tomato in the sauce: Russian Doll Season 1 couldn’t be anything but television. If you ran it all together into one 3.5 hour watch, which many of us did, the story and rhythm is still completely distinguishable as eight distinct episodes, each with their own internal arc and tone that you can easily recall later—the episode where Nadia thinks the yeshiva is haunted, the episode where they’re going through Alan’s day together looking for clues, the episode about Nadia’s childhood trauma, et cetera. This was something I thought about a lot in 2019 when I first watched it, how it binged so well yet still has this nicely chaptered form. Like an album, co-creator Leslye Headland has described it, you can listen to the whole thing through but it’s composed of individual songs. This is a really good analogy. Another would be: like television. But in the era of streaming limited series that just formlessly run on to their end, often without even opening credits* to set off new episodes anymore, that classic television structure can be rarer and rarer to find.

In fact, if you look ahead to just the next season of this show, you won’t find it! Russian Doll Season 2 is no longer a story built episode by episode, like building blocks that each contain their own kernel of color and meaning, it’s a concurrent & continuous narrative that has just been arbitrarily cut at about each 30 minute mark. You can tell by how this time, it is much more difficult to recall later which episode something happened in. Somehow the episode where we finally find out what Alan has been up to is also the episode where Nadia and Maxine go off to Budapest for like 36 hours—that should not happen! That is so befuddled! It’s something you might not pinpoint at the time, but this simple lack of internal episodic cohesion is absolutely a part of what makes this season feel more scattered and unsatisfying compared to the first one.

It’s so interesting that it feels more jumbled, because on paper, Season 2 actually has a much more clear and specific topic it’s addressing, what it’s About, than Season 1 does, with its poetic, (theatrical), open-ended conclusion that just doubled down on letting everyone draw the takeaway that mattered most to them. No one is writing explainers this time of the different themes, or self-effacingly airing their extremely niche pet theories about the Tompkins Square Park Riots that turn out to have something there. There’s no need: Season 2 is expressly about inherited trauma, all roads lead to Rome (or the past, rather). Yet by the time this journey wraps up, what is the impactof this new season? Rather less? The widely middling reviews and near entire lack of Season 2 on my dash when everyone had been posting about Season 1, all seem to indicate yeah, less.

What I think these two seasons demonstrate so well is that the power of narrative art forms often depends less on just what their ideas are, than how those ideas are being conveyed, what storytelling methods are being used to get atthem. The interests of this season are absolutely of a piece with the first, in fact I think most of it was first brought up in the scene where Nadia and Alan are getting drunk at the bar. He mumbles that her necklace is pretty, and she lays out this history of her family fleeing the Holocaust and the story of the gold coins and how her ill mother in her delusions lost them, all but one, and she’s blithe and sad and drunk, not as drunk as Alan but in keeping with him, her eyes are a little bright and she’s feeling confessional and shocking, and it’s so powerful. There is so much in this inter-generational tragedy to delve into, and Season 2 is doing that! It’s about these things and these characters we were already invested in, this should be great, so why does it fall flat when we’re actually watching it? STRUCTURE.

Okay, so these two seasons are basically going about themselves from opposite directions:

Season 1 is structure-led: it sets up a framework (death time loop), and the characters are set loose to quite literally batter themselves against it in an attempt to find meaning (each other) (healing) (self-peace). Our two protagonists are constrained at nearly every turn by this shape the show has place placed them in, yet the sparks of their humanity bumping into it creates some of the brightest parts—the amount of revealing Maxine & Lizzy moments that come from Nadia refusing to leave via the stairs after episode two; Alan hurriedly telling a gasping Nadia where he’ll meet her if they’re dying as blood starts to trickle out of his ear; the fucking song.(*Oh we’ll come backto this!)

Season 2, meanwhile, has a different starting point: it sets up a discussion topic, and pretends to have a new structure (time train), but from the very beginning, the rules of the 6 train change depending on whatever the story wants to be about at that moment—it’s story-led, 100%. Season 1 was beholden to its form, to the point of occasionally feeling like both we and the characters were trapped in one of Nadia’s video games. Season 2 is not actually constrained by any form at all, but instead of this freedom letting the show burn brighter, we lost those edges to spark against. Everything ended up feeling more diffuse and watery, until our lead characters were literally wading through it. Notably: apart. (We’ll get to this too!)

Season 1 tells a story that can be understood to be about a lot of different things, in a setting that is so wonderfully specifically one thing—culturally, geographically, calender-ly. Season 2 tells a story clearly understood to be about one thing, in a setting that now includes three different cities, four different time periods, and eventually a sort of collapsing multiverse of timelines. They’re opposites!

And I think I have an idea of why one (1) works better. We’re going briefly to the stage, actually. (Hang with me!)

In an interview on Little Gold Men about his adaptation of Tick, Tick, Boom!, Lin Manuel Miranda said something that caused me to say for the second time (the first time was when I was watching Tick, Tick, Boom!), “Aw man, you’re a good director.” What he said he was this:

“Yes, the musical theater truism of the opening number establishing the rules of the world, is important. You have to tell the audience how to experience this show, and how does the singing work, and what are we watching. But I also learned on Hamilton that every number is an opportunity to renegotiate that relationship, and crack it open a little more and bend the rules here. […] Establishing all those rules with every song and pushing on those rules, so that by the time we get to the end of the show, we can literally stop time.”

As a nerd for structure, this really spoke to me. Sure it’s initially about musical theater, a unique medium with its own tool set, but it also applies perfectly to a season of television like Russian Doll Season 1, where instead of each song, it’s each restart of the time loop that is an opportunity to re-establish the rules while also pressing on them.

Speaking of songs! Let’s get to this now: the diegetic music cue of Harry Nilsson’s ‘Gotta Get Up’ playing on each restart is such a stroke of genius. On one level, it let them hack the no-credits format of Netflix’s recent years—it’s now the credits song! It signifies one little narrative close and the start of a new one! We’re humans, we love patterns, and we also love when patterns alter in satisfying ways. Studies on people who experience frisson, goosebumps while listening to music or even just watching or reading a narrative, have found that it usually comes at key pattern moments, either when the current pattern breaks, or when it reforms into a pattern from earlier. The same ‘Gotta Get Up’ track playing from the same exact spot every single time was a thrill of repetition, but ALSO an incredible barometer for how the show was making us feel at that moment, as the song’s tone would almost seem to alter as we went on. Sometimes it would feel more manic, other times more ominous, others more hilarious, more moribund, more surreal. It’s so eeriewhen it’s playing in Maxine’s now fully empty apartment, and so joyouswhen it’s playing and everyone’s back.

BecauseRussian Doll Season 1 is perfectly following that musical theater adage. As Lin would have it, each ‘song’ (each restart): an opportunity. Season 1 is miles more rule-bound than Season 2, but that doesn’t make it static at all. In fact, it’s continuously using what we know of the structure to reveal new things to us, either by something’s sudden absence or sudden appearance in what we had grown to think of as a sealed loop. Paradoxically, each time we learn another rule, the world expands.

Most importantly, indelibly: the end of the third episode—

Nadia: “Hey man, didn’t you get the news? We’re about to die.”

This guy in the elevator: “It doesn’t matter, I die all the time.”

Fun fact, so I get frisson? I got frisson just now simply thinking about this moment. IT’S PERFECT TELEVISION WRITING. It feels WILD, it’s SO surprising, but it’s also not actually breaking our rules at all, it’s simply revealing to us a new person who is also subject to them. And we didn’t know!! The panic over “spoilers” that has grown up in recent years is, I think, rather overblown, but I will say that’s one thing about Netflix keeping Russian Doll a secret and just dumping “a new Natasha Lyonne show” on everyone with no warning one week in February 2019: we didn’t even know there was a second lead character. If I had seen even a single still of Charlie Barnett before watching it, I didn’t remember. Top ten TV moments of my life!! And that we KNEW the next episode was going to start with him looking into a mirror, you just knew it! That predictive joy of pattern & surprise!

And then the existence of Alan immediately offers so much. For starters, someone for grousing, gravelly Natasha Lyonne to play off of (wonderful), but what I think I might find most moving is the discovery that bears down on you the minute we start that next episode—'Alan’s Routine’, it is tellingly titled—that oh, oh he is trying to handle this completely differently. I know I keep saying similar things, but it’s my refrain: it’s the structurethat is allowing us to so quickly get this depth of characterization, and a deeper understanding of Nadia as well, just through their differing responses to the same time loop. It’s so important to what that season is trying to do with its central existential pondering that this be happening to them in the same way, but because of who they are as people and the circumstances of their personal histories, they’ve each started to build up a totally different mythos of how and why it works (god, god, it’s so good).

But then in Season 2, we actually barely get Alan at all, and even when we do they’re quite cordoned off from each other. I love Alan and missed him, but it’s not just that—I love them together. Nadia sets off Alan at his best angles; Alan sets off Nadia at her best angles. I really think another part of what makes the developments of this season feel oddly skimmed over sometimes is that neither of them has the other there to question and comment and collaborate. Imagine Alan providing cover for Nadia, heist-style, as she slips into that Budapest auction house basement, and then supporting her with the emotional weight of what she finds there. Imagine Nadia’s reaction to Alan’s reaction to getting catcalled by Stasi officers who see him as his young grandmother.

I do think that even without the unavoidable comparison with the story of connection that had come before, the writing of this season would have still felt disjointed between them, Alan’s unrelated Berlin B-plot tacked on to the clear A-narrative of Nadia and the krugerrands. Sure, stories don’t always have to have the fates of the characters intertwined to be moving, but it generally makes for more rewarding experiences when there are these thematic echoes, these exchanges between people, when they change each other. Part of the beauty of that first season Russian Doll was that as it went on, we all began to realize, Nadia and Alan too, that it was only going to be through helping each other that they were going to be in less pain. I don’t know if I can save myself, but perhaps I can save you. It’s lovely.

Season 2 is more of an individual journey. It’s basically Nadia and Alan now doing work on themselves, on their own. It is a stepping back from where Season 1 ended, or maybe a step inward I mean? And I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, just as I don’t think that every story has to be highly structured to be any good (of course not!). But I do think that more loosely organized individualism can be harder to manage from a storytelling perspective. It can, as this second season does, tend toward meandering. It can, as this season does, lose awareness of rhythm. Those patterns, building and breaking and reforming. Those constraints that create beauty. Season 2 cut itself loose from form, when it needed structure more than ever.

But hey, it really did make me fall even more in love with that first season, and I don’t know if I would have thought that was possible.