#lucian freud

With the world turned upside down, we could all use something to look forward to—so, for the next few weeks, we’ll be highlighting our new season of books coming in the fall. First up are four new nonfiction titles from our New York Review Books series, all arriving in September: a literary biography of Balzac, a memoir on loss, the autobiography of an artist too long mistaken for a muse, and a collection of entire essays on single sentences.

Peter Brooks, Balzac’s Lives

Balzac’s massive exploration of French society, The Human Comedy, is said to have invented the nineteenth-century novel, if not the nineteenth century itself (according to Oscar Wilde). Here, writer and scholar Peter Brooks examines the man behind the masterpiece in a vivid and searching study that is based on a close examination of his extraordinary characters—from the capitalist Gobseck to the gay criminal mastermind Collin.

Dorothy Gallagher, Stories I Forgot to Tell You

Dorothy Gallagher’s husband, Ben Sonnenberg, the author of Lost Property: Memoirs and Confessions of a Bad Boy (out in June), died over a decade ago after a long battle with multiple sclerosis. In Stories I Forgot to Tell You, she moves between present and past, the smallest moments of life with her husband and her life after him. It’s a quirky and profound portrait of love, of loss, and of two writers sharing a life.

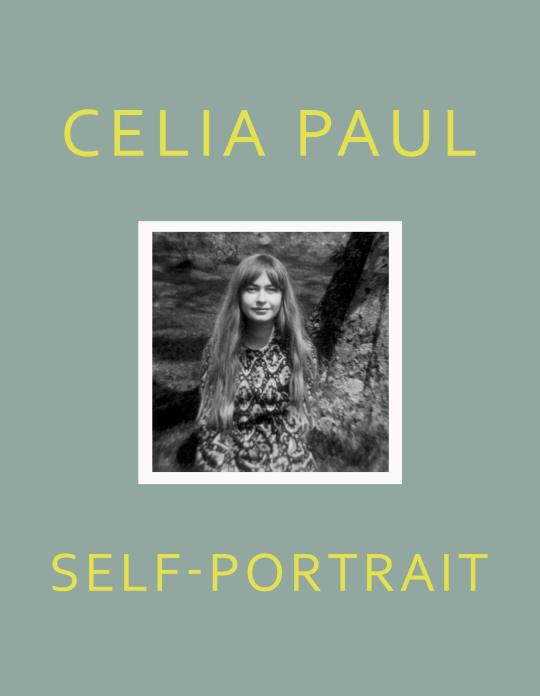

Celia Paul, Self-Portrait

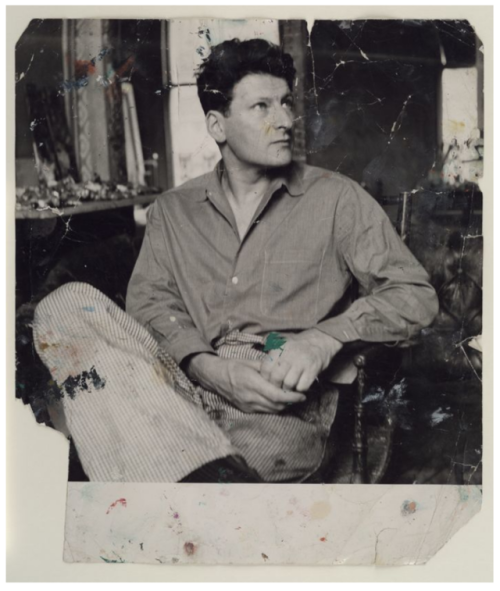

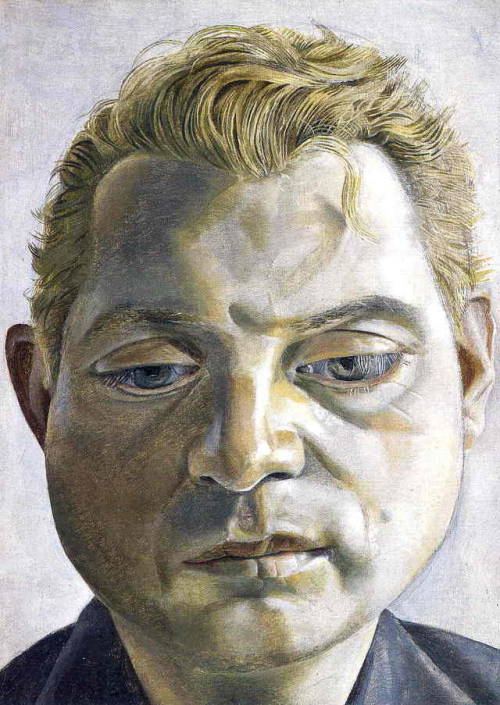

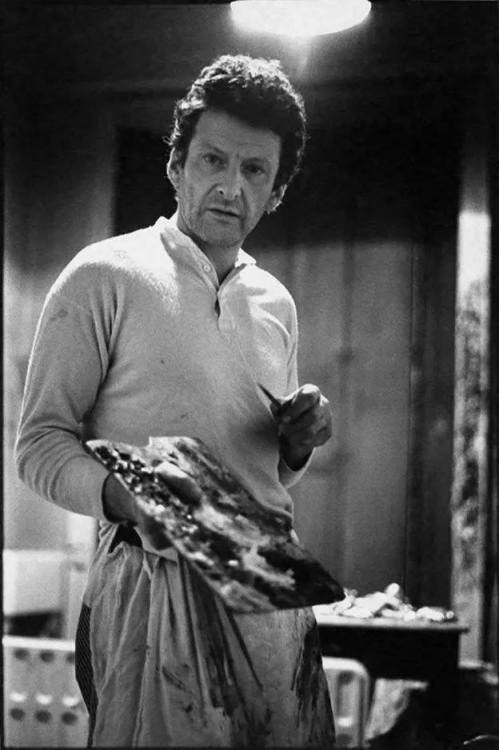

Celia Paul, one of Britain’s greatest painters alive today, lived long in the shadow of the domineering artist Lucian Freud: their decades-long relationship began when she was eighteen and he fifty-five. This intimate, introspective memoir puts her finally at the center of her own story, with poignant reflections on Freud as well as childhood, family, and motherhood, and above all her unyielding dedication to art.

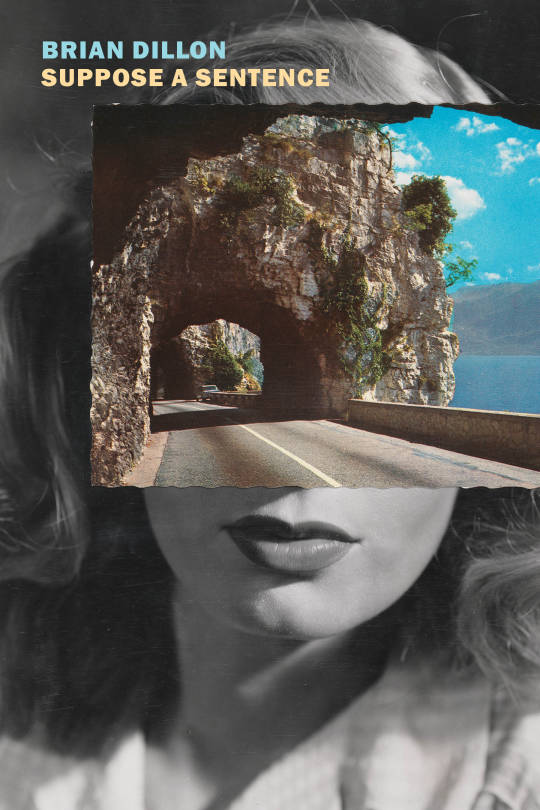

Brian Dillon, Suppose a Sentence

Brian Dillon’s last book, Essayism, was a roaming love letter to literature’s perhaps most indefinable form. In this collection, he offers a series of essays prompted by a single sentence—from Shakespeare to Janet Malcolm, John Ruskin to Joan Didion—exploring style, voice, language, and the subjectivity of reading.

Lucian Freud, Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening (Self-Portrait), 1967-69, oil on canvas

Post link

Today’s Flickr photo with the most hits: this 1947 canvas by Lucian Freud - Girl with Kitten (Kitty Gorman).

Post link

Mark Doty

I love starting things

*

Fat and shadow, oil and wax,

mobility solidified,

like cooled grease in a can –

*

Seeing how far I can go

*

Analiese said, happily, ‘He paints the ugliness of flesh,’

but that isn’t it: flesh without the overlayer, how we ought to see it,

all we’re taught –

January sky over Seventh. To the north,

a slab of paraffin. A wax table. Then it pinks,

shifts, at the most complicated hour, after sunset, before dark, the lamps already on. A deepening blue at the sky’s centre, but the tops of the buildings still warmed by the last of sunlight,

the way he fixes the face at its most subtle hour

*

One of the things that makes you continue is the difficulty surely

*

all the decisions of colour revealed, light making available every nuance of a (sur)face so plainly itself it’s become plea and testament.

*

Ugly: resist the term, or open it: the living edge resisting?

Surface the heart of the matter.

Strange achievement: to see skin

as no one else.

*

Never any beauty

greater than the body hung in the ceaseless wind of time

and repeating in that current its stream of postures,

skin perpetually lit from within

as if by its own failure –

*

When I paint clothes I am really painting naked people who are covered in clothes

*

January in grisaille.

Sarah and Lucy erased,

weirdly euphonious terms:

lymphoma, heroin.

Then an anonymous body

on the sidewalk,

a fifth-floor room onto Sixth Avenue,

the aching window open all afternoon.

A man on our block

pulled from his car and beaten

with a tyre iron by another driver

who wanted him to hurry up

and pass the garbage truck.

Flesh fails and failure

is visited upon it.

The book of Freud’s paintings

a brooding invitation, catalogue

of human suspension in time

and today I think they’re an oil

and pigment howl,

outpouring against limit.

But as soon as I’ve said it,

the old argument resumes,

the ambiguity of vanitas:

do these paintings of dying things

warn or celebrate,

does their maker caution or consume?

My life in the fields of this argument,

shifting skin

the live veil,

elongated grammar of muscle,

this moment’s agreement of light

on the pure actual. (No such thing as the body,)

Fact of a wrist.

Vein troubling a forehead.

Melville: How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall?

*

(By the waterfountain in the gym)

On the huge man’s left arm TRUST

above an image he called the god of joy

on his right forearm

inscribed above the veins

a centaur

symbol of leadership he said

of direction

I couldn’t speak, in some deep basement of myself thinking

Maybe his great body is the fact

I require …

the dream of being realised

And half the night I’m thinking

of the immense human wall

and veil of him. What is it

we want from a body;

the lying-awake longing,

to what does it attend? Whitman:

These thoughts in the darkness why are they?

*

Clothing veils

the real;

flesh conceals –

what to call it?

quick lively presence quickening

through the lidded eyes,

a moment’s sharp attention,

the painting looking back at us?

*

The mystery isn’t mind

(what else are we, evidently,

besides aware?)

but materiality, intersection

of solidity and flame,

where quick and stillness meet –

Materiality the impenetrable thing.

We don’t know what it is

other than untrustworthy –

all bodies, even the young,

who rightly think

they’re untouchable:

that faith’s their signature

and credential.

I am a body less reliable,

and therefore the rough-scumbled peaks

of these faces thrill, familiar –

aspects of flesh breaking here,

the way we say waves break –

become visible at the instant

of their descent.

Caught somewhere in the arc.

How will these look

in a hundred years?

Stunningly here.

*

Intricate wall

of appearances –

lit at its highest entablatures,

water towers and rooftops, cornice and capital,

smokestack and chimneypot picked out

by the glow slanting across the river,

intensified Hudson-light,

and warm lamps in the high windows,

neon over the shopfronts

flickering on;

world of consummate detail,

the city lay back, shambling, corpulent, nude … (why he loves the big frame: because it is no longer

flesh but the flesh)

*

Nothing ever stands in for anything. Nobody is representing anything.

*

My god: every body

of a piece, every factual expanse of skin,

the contour of them –

that’s what language can’t do, curve and heft of it,

that stretch … Oil and shadow,

fat and wax, grief solidified.

There’s no one else.

You and I the common apprehension of this.

*

Our chests open, arms back,

the teacher said, ‘This is a position

of FIERCE VULNERABILITY – ’

I thought, that’s it, that’s

exactly a position one could live

toward, to stand in permeable faith,

and yet such force in that stance,

upright, heart thrust out

to the world, unguarded, no hope

without the possibility of a wound.

‘To hold oneself in this pose,’ he said,

‘takes incredible strength.’

*

Everything is autobiographical

*

I look at his pictures and want

above all language muscling up,

active work of pushing out some sound,

throat and muscle of the tongue,

some hope of accuracy –

*

and everything is a portrait, even if it’s a chair

*

Accuracy? Go on, then –

to write the tragedy of this body

*

I want to go on until there is nothing more to see

Today’s Flickr photo with the most hits: this Lucian Freud canvas at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Post link

Naked Portrait and a Green Chair by Lucian Freud, 1999.

Grandson of Sigmund, Lucian Freud (who lived most of his life as a recluse in London) also had a preoccupation with human sexuality–but they approached the subject in different ways.

Whereas the first Freud focused on theory, his descendant preferred empirical research.

One left a legacy of concepts such as penis envy, castration anxiety and the Oedipal complex.

The other left at least 14 children.

That’s a conservative estimate, by the way. Some people have speculated that the number is closer to 40.

His models remember Lucian as a charming but demanding painter who sometimes relied on seduction to attain his artistic vision. The art that resulted tended to be stark (or grotesque, some critics said) with no concessions to romance, but he found beauty in bodies in the absence of glamour.

Two of his daughters posed for their absent father in order to get to know him. Now what would Sigmund have thought about that?

Even before he died in 2011, Lucian’s work was selling for as much as $33 million at auction. Whether he had 14 heirs or 40, presumably his estate was generous enough for all.

Post link