#northern renaissance

Jan van Scorel, The Tower of Babel, 1550, oil on panel, 58 x 75 cm., Galleria Giorgio Franchetti alla Ca d'Oro, Venezia.

Post link

Joachim Patinir (attributed), The Building of the Tower of Babel, 1500-1524, oil on panel, 74 x 103 cm., Brighton and Hove Museums and Art Galleries,

Post link

Jan van Scorel, Tower of Babel, c. 1530, pen in brown ink, traces of black chalk on paper, 300 x 445 mm., Collection Frits Lugt, Institut Néerlandais, Fondation Custodia, Paris.

Post link

Hendrick van Cleve III, The Tower of Babel, 16th century, oil on oak panel, 61 x 72 cm., Private collection.

Post link

Unknown painter, The Tower of Babel, c. 1590, oil on wood, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

Post link

Here’s a little Friday morning personal inspiration with a snippet of The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1562. In this oil panel painting, Bruegel combines visual elements of Northern woodcuts of the Dance of Death, as well as concepts and styles seen in the the Italian fresco The Triumph of Death from Palermo. I love Northern Renaissance paintings and pieces with tons of strange little scenes and hidden symbolism. I also just love armies of skeletons. ☠⚔

Post link

modern-vampires-of-art-history:

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (1530) / Vampire Weekend, Horchata (2010)

Post link

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (1530) / Vampire Weekend, Horchata (2010)

Post link

The Ambassadors[1533]

- Featuring an anamorphic skull in foreground of painting. Fantastic 16th century work in perspective.

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger

Post link

‘bacchus’ - jan van dalen (1648)

HUMANIST PORTRAITURE IN RENAISSANCE ENGLAND

As Lord High Chancellor of England, the humanist scholar and author Sir Thomas More was the highest ranking official of King Henry VIII’s court and one of the wealthiest men in England. In 1527, More commissioned Henry’s Swiss court artist, Hans Holbein the Younger, to paint a group portrait of his extended family. The monumentally-scaled picture, depicting 12, highly-individualized figures in a unified spatial setting, executed in deep, jewel-like colors, set a new standards of invention, complexity and quality hitherto unparalled in English panel painting.

Holbein placed More at the center of the composition. His father, the judge Sir John More, is seated to More’s right and his only son, John, stands to his left. Just beyond the family’s patrinlineal core, is Holbein depicts More’s daughters: Elizabeth Daunce attends to Sir John, while Cecily Heron and Margaret Roper are seated at right. More’s second wife, Lady Alice More, is seated at the far right. Her daughter from her first marriage, Margaret Giggs, stands at the far left. Anne Cresacre, of Sir Thomas and future wife of John, stands behind the Sir John. Also included in the portrait are the household ‘fool,“ Henry Patenson, in orange, and More’s clerk John Harris. All figures are identified by Latin inscriptions.

More’s wife and children all hold books. Some are shown reading, while others pause to reflect with their books either open or mark their place with a finger. The clerk, entering from the right, carries a scrolled document, no doubt intended for Sir Thomas. More books and musical instruments are displayed on a shelf and a large pendulum clock hangs on the rear wall. As he would later do in The Ambassadors, Holbein conspicuously represents these objects to emphasize the literate and learned humanist culture of More’s household. An advocate of the education of women, More educated his wife, daughters, and son in the same liberal arts cirriculum. The panel’s latin inscriptions would have posed problems for no members of the family. Margaret Roper’s mastery as a translator of Greek and Latin was widely acknowledged by More’s humanist peers, including Erasmus.

The deeply-pious More had briefly entered a Carthusian monastery prior to embarking on his political career and his profound Christian belief influenced his theories of humanist education. Margaret is therefore seen reading Seneca’s Œdipus, while Elizabeth carries his Epistolae under her arm. These texts, along with The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, seen on a table, represent ancient Stoic philosophy held to be compatible with Christian values. Further indications of the family’s Christian piety include the crucifix worn by Patenson, the rosary worn by Margaret, and the red cross suspended from Elizabeth’s choker. Flowers associated with the Virgin Mary – lilies, carnations, columbine, iris and peony – are displayed in vases around the room.

Painting served an important purpose in More’s learned circle. In 1517, his friends and collaborators Erasmus and the scholar-editor Pieter Gillis (one of the dialogic participants in More’s Utopia), commissioned Quentin Matsys portraits of themselves, showing them at work in their studies, as gifts for More as tokens of their intense intellectual bond.

More’s resistance to Henry VIII’s ecclesiastical policies led to his execution in 1536. His family portrait survived, with several later additions and alterations, until it was destroyed in a fire in 1752. Today, it is known through two 16th-century copies and Holbein’s exquisite preparatory drawings.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Sir Thomas More, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Study for the More Family Portrait, 1527, Basel, Kunstmuseum; after Hans Holbein the Younger, Margaret More Roper, 16th c, Knole, National Trust; after Hans Holbein the Younger, Lady Alice More, 16th c., Private Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Elizabeth More Daunce, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Anne Cresacre, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Margaret Giggs Clement, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, John More, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Rowland Lockey after Hans Holbein the Younger, More Family Portrait, 1592, Nostell Priory, National Trust; Hans Holbein the Younger, Sir John More, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Cecily More Heron, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Quentin Matsys, Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1517, London, Royal Collection Trust; Quentin Matsys, Petrus Egidius, 1517, Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen.

Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390–1441) and Workshop Assistant. The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment, ca. 1440–41. Oil on canvas via the METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, USA

What an extraordinary detectiv

estory this has been!We started with the unexpected discovery of a hidden text on the frames of Jan van Eyck’s Crucifixion and Last Judgment, and then leveraged scientific research to help determine what was original to the paintings and what was not. The decision was made to restore the frames to their intended red color, and, finally, an ace paleographer deciphered the fragmentary Middle Dutch biblical text, which turned out to be a translation of the Latin pastiglia on the inner cove of the frames.

The result of the thrilling teamwork involved in this investigation is that, all together, we have been able to return these frames—an essential, integral part of Van Eyck’s conception for the paintings—to a state that is closer to what was originally intended. Now thinking back to the modern gold-colored (brass actually!) restoration that had hidden all of this information for many decades, it is hard to even conceive of such a misconception. The red frames look so genuine and compatible with the aesthetic of the paintings that any other solution is not imaginable. Now that the paintings have been reinstalled in their frames, they are back on view in gallery 641. There is enormous satisfaction in realizing, and then being able to implement, what was envisioned by Van Eyck and the unknown individual who commissioned the work. We can now appreciate how the Crucifixion and Last Judgment served to aid the priest celebrant and various worshippers in their devotional practices. Kneeling before these exquisite and detailed depictions of the stories of the Crucifixion and Last Judgment, the viewer was encouraged simultaneously to become immersed in Van Eyck’s paintings and to read the biblical texts that he so carefully coordinated to go with them.The Latin inscriptions on the cove of the frames were in the language known to the priest, but clearly these texts needed to serve a wider audience; the Middle Dutch translation—the vernacular language of the time—was therefore added in order to allow a less learned participant to fully engage in the same devotional experience. In this way, the production of the artwork facilitated the meaning and use of the paintings in their own time.Although there are still other ongoing investigations of these masterpieces of The Met collection—namely their patronage and the evolution of their form, likely from tabernacle doors to a diptych and to triptych wings—we have unraveled at least some of the mysteries that these works still hold. The results of our further research on these glorious paintings will appear in their online collection entry and in future publications.

Post link

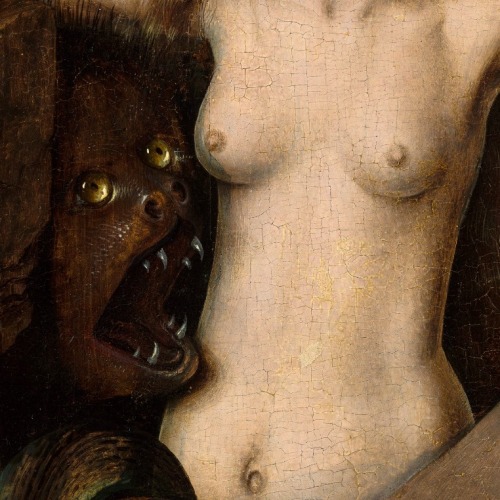

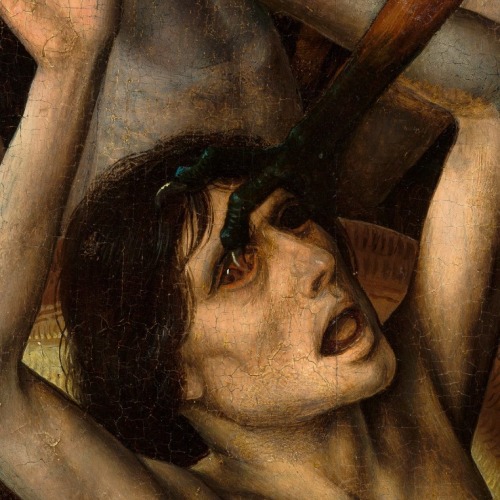

Hieronymus Bosch, Ecce Homo (detail), 1475-1485. Tempera and oil on oak panel, 71 cm × 61 cm. Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

In the 2016 documentary “Exhibition on Screen: The Curious World of Hieronymus Bosch,” they pointed out a detail I never noticed in this Ecce Homo: Christ’s bloody footprint.

Although this is a painting and not a photograph, it reminds me of the idea of the “punctum” of a photo as “that… which pricks me… bruises me, it poignant to me” (1). Roland Barthes went on to talk about how “while remaining a “detail,” it fills the whole picture,” and has “a power of expansion” (2). For early modern viewers of this painting, it’s possible to imagine how this footprint (and the detail of the cuts on Christ’s legs, which were depicted by a number of Northern painters, including as Matthias Grünewald in the early 16th-century Isenheim Altarpiece) would function as a visceral reminder of the pain Christ endured.

Throughout the early modern West, graphic and emotional images of Christ suffering (like this one) were produced for religious settings as well as private ones, where they could serve as personal devotional objects. Titian’s intimate 1547 Ecce Homo and Veronese’s 1584-1585 Christ Crowned with Thorns both depict Christ in a red cape or robe, his eyes lowered as blood drips down his face.

1. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 27.

2. Barthes, Camera Lucida, 45.

Post link

Robert Campin, The Virgin and Child, c. 1410

One of three panels in a triptych, this painting depicts the Virgin Mary and an infant Christ at her breast.

Source: Web Gallery of Art

Post link

![The Ambassadors [1533]- Featuring an anamorphic skull in foreground of painting. Fantastic 16th cent The Ambassadors [1533]- Featuring an anamorphic skull in foreground of painting. Fantastic 16th cent](https://64.media.tumblr.com/419d7596b9611b1d6776951b4365c008/f566370abaaac4d3-8c/s500x750/ac8f6ef219be8ef55686ed31207beceb921552e7.jpg)