#medieval women

“Consider the Vikings. Popular feminist retellings like the History Channel’s fictional saga “Vikings” emphasize the role of women as warriors and chieftains. But they barely hint at how crucial women’s work was to the ships that carried these warriors to distant shores.

One of the central characters in “Vikings” is an ingenious shipbuilder. But his ships apparently get their sails off the rack. The fabric is just there, like the textiles we take for granted in our 21st-century lives. The women who prepared the wool, spun it into thread, wove the fabric and sewed the sails have vanished.

In reality, from start to finish, it took longer to make a Viking sail than to build a Viking ship. So precious was a sail that one of the Icelandic sagas records how a hero wept when his was stolen. Simply spinning wool into enough thread to weave a single sail required more than a year’s work, the equivalent of about 385 eight-hour days.

King Canute, who ruled a North Sea empire in the 11th century, had a fleet comprising about a million square meters of sailcloth. For the spinning alone, those sails represented the equivalent of 10,000 work years.”

“…Picturing historical women as producers requires a change of attitude. Even today, after decades of feminist influence, we too often assume that making important things is a male domain. Women stereotypically decorate and consume. They engage with people. They don’t manufacture essential goods.

Yet from the Renaissance until the 19th century, European art represented the idea of “industry” not with smokestacks but with spinning women. Everyone understood that their never-ending labor was essential. It took at least 20 spinners to keep a single loom supplied.

“The spinners never stand still for want of work; they always have it if they please; but weavers are sometimes idle for want of yarn,” the agronomist and travel writer Arthur Young, who toured northern England in 1768, wrote.

Shortly thereafter, the spinning machines of the Industrial Revolution liberated women from their spindles and distaffs, beginning the centuries-long process that raised even the world’s poorest people to living standards our ancestors could not have imagined.

But that “great enrichment” had an unfortunate side effect. Textile abundance erased our memories of women’s historic contributions to one of humanity’s most important endeavors. It turned industry into entertainment.

“In the West,” Dr. Harlow wrote, “the production of textiles has moved from being a fundamental, indeed essential, part of the industrial economy to a predominantly female craft activity.””

- Virginia Postrel, “Women and Men Are Like the Threads of a Woven Fabric.” in The New York Times

A different subject, of course, but this post nonetheless made me think of this passage from The Herb of Grace by Elizabeth Goudge:

It was homemaking that mattered. Every home was a brick in the great wall of decent living that men erected over and over again as a bulwark against the perpetual flooding in of evil. But women made the bricks, and the durableness of each civilization depended upon their quality, and it was no good weakening oneself for the brick-making by thinking too much about the flood.

gotta love the fact that of the two lives of St Radegund, the one written by a nun is all about her good work for the community and the one written by a monk is torture porn.

this is from the Vita Radegundis of the nun Baudonivia:

(that attitude. i’d literally let radegund drive her horse over me.)

and this is from her Life by Fortunatus, who clearly had a problem (proceed with caution: very violent self-harm)

gotta love the fact that of the two lives of St Radegund, the one written by a nun is all about her good work for the community and the one written by a monk is torture porn.

A poem by the Welsh female poet Gwerful Mechain (Gwerful of Mechain in mid Wales, born about 1462, died 1502) in praise of the vagina, in which she laughs at other poets for never mentioning it in their own eloquent writings in praise of women’s bodies.

The illustrations in this version show (top right) Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit, and (bottom left) Bathsheba bathing (with King David watching her in the background).

Post link

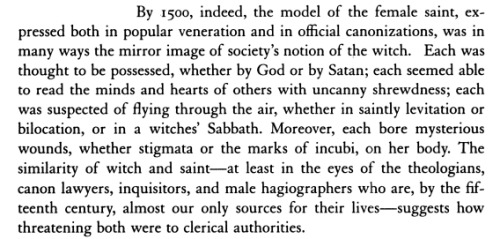

Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women

Post link

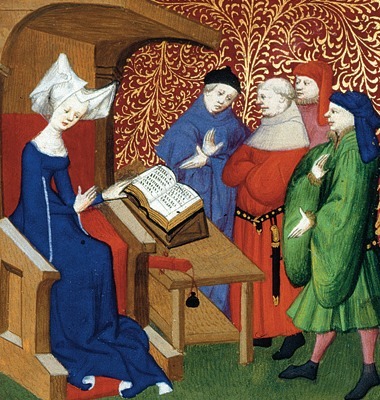

Author, historian, poet, philosopher

Born 1364 or 1365 – Died 1430 (age 65 - 66)

Claim to fame: An advocate for women’s education, Christine is the first European woman known to have made her living as a writer.

Born the eldest child of the personal physician to King Charles V of France, Christine was well educated and benefited from access to the King’s vast library.

Christine was married at 15 and widowed just 10 years later. After her husband’s death, she turned to writing to support herself and her family, serving as a court writer for several dukes as well as Charles VI of France.

Her 1405 book, ‘La Cité des Dames’ (‘Book of the City of Ladies’), catalogued female accomplishment and helped establish her popularity. This book is considered by many as the inaugural text in the field now known as women’s studies.

Christine completed forty-one works during her career. Her work contradicted negative female stereotypes and countered unjust slander of women within other literary texts. She argued that women have the same aptitudes as men and thus the right to the same education. Christine’s influence in the otherwise male-dominated field of rhetorical discourse lead Simone de Beauvoir to acknowledge her as the first woman to “take up her pen in defence of her sex”.

Post link

Uta von Ballenstedt

Margravine of Meissen

Born c. 1000 — Died pre-1046

Uta was a member of the House of Ascania. Through her marriage to Margrave Eckard II, she was the Margravine of Meissen in Saxony, eastern Germany.

Presumably to promote the rise of the Ascanian dynasty, Uta’s father married her to Eckard II in about 1026. However, the marriage produced no children, resulting in the extinction of the Ekkeharding dynasty.

The couple contributed a significant amount to construct what would become the Naumburg Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul.

When the Cathedral was completed in the mid-13th century, the presiding bishop honoured the founders, Ekkehard, Uta and 10 other nobles by commissioning the anonymous ‘Naumburg Master’ to produce life-size painted statues of them to adorn the cathedral. The sculptures are remarkable as secular rather than biblical decorations for the cathedral, particularly as they depict nobles rather than kings or emperors. The depictions are now generally considered masterpieces of Gothic art.

In the 20th century, the statue of Uta was used by the Nazi’s as a prototype of the ideal Aryan woman, even appearing as an Aryan role model in Fritz Hippler’s propaganda film The Eternal Jew.

It is also believed that the statue inspired the depiction of the Evil Queen in Disney’s 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. You be the judge!

NB: the dates from when her image was used to depict a ‘Teutonic Madonna’ in various Nazi propaganda makes me wonder if that was why her likeness was used to represent an evil character in the Disney film. Just a thought!Post link

Jeanne Laisné (nicknamed Jeanne Hachette - ‘Jean the Hatchet’).

Born 1456 - died ?

Claim to fame: a French military heroine who prevented the capture of Beauvais.

In June of 1472 Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, laid siege to the French town of Beauvais. Over the course of the three week siege, a peasant woman named Jeanne Laisne joined a contingent of women and children responsible for loading the town’s cannons, delivering munitions and dumping boiling liquid over the walls onto the attackers.

By 27 June, many of the French defenders had lost hope and begun to flee as an assault from the Burgundians seemed set to defeat the town. An officer was about to plant the Burgundian flag on the wall and claim Beauvais when Jeanne grabbed a hatchet and flung herself upon him, hurling him off the wall and tearing down the flag. Her bravery revived the courage of the garrison and the French soldiers returned to their posts, keeping the Burgundians at bay until reinforcements arrived and the town was saved.

By way of recognition, King Louis XI heaped favours on Jeanne and ordered for the ‘Procession of the Assault’ to take place in Beauvais every year with women marching at the head of the parade. This tradition still continues.

In 1851, a bronze statue sculpted by Gabriel-Vital Dubray (pictured above) was unveiled in Beauvais by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte.

Post link

The nobility of your forbears magnified you, O Edith,

And you, a king’s bride, magnify your forbears.

Much beauty and much wisdom were yours

And also probity together with sobriety.

You teach the stars, measuring, arithmetic, the art of the lyre,

The ways of learning and grammar.

An understanding of rhetoric allowed you to pour out speeches,

And moral rectitude informs your tongue – Godfrey of Cambrai, prior of Winchester Cathedral (1082-1107)Edith of Wessex was born c. 1025, the eldest daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and his wife Gytha. Her family was a formidable one: Godwin was one of the most powerful men in England, while Gytha was the sister-in-law of Cnut.

She was raised at Wilton Abbey, which she later had rebuilt as a sign of gratitude. There she learned Latin, French, Danish, and some Irish as well as grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, weaving, embroidery, and astronomy. There is little else we know about her early life apart from her education, but she seems to have been especially close to her brother Tostig.

Edith’s father, Godwin, had a troubled relationship with King Edward the Confessor because Edward believed that Godwin was responsible for the death of his brother. Even so, Godwin was the most powerful man in England and Edward needed his support, and so married Edith at Godwin’s behest on 23 January 1045.

The relationship does not seem to have been a particularly romantic one. They were 20 or so years apart in age and he disliked her family, but all the same she had some influence and it was said that she always advised Edward wisely, and did a lot to improve his kingly image.

In 1051, Godwin and Edward’s relationship significantly deteriorated. Rather than risk arrest, Godwin fled the country with his sons. Edith was sent to a nunnery and all her lands confiscated, perhaps because he didn’t like her, thought they had little hope of conceiving together and wished to remarry, or simply wanted to get revenge on her father. The next year Godwin returned to England and civil war looked likely, but Edward lacked support and was forced to restore Godwin’s lands to him and reinstate Edith as Queen.

Though the two were still unable to have children (probably not because Edward had taken a vow of chastity, as is often said), Edith’s influence as Queen grew, as is shown by the increase in the amount of charters she witnessed, and she joined the circle of Edward’s most trusted advisers.

In 1055, Edith’s brother, Tostig, became Earl of Northumbria but his rule was hugely unpopular and 10 years later the local Northumbrian population rebelled, killing Tostig’s officials and outlawing him, asking instead to be ruled by a member of the leading Mercian family. There is some evidence that many of the Northumbrian people viewed Edith as complicit in Tostig’s tyranny, and indeed it’s likely that she herself had one of Tostig’s political enemies assassinated. Finally, one of Edith’s other brothers, Harold was sent to deal with the matter. He agreed to the rebels demands, depriving Tostig of his earldom, and Tostig, who fled to Flanders, never forgave Harold, nor did Edith.

On 5 January 1066, Edward the Confessor died, leaving Edith’s brother as King Harold II. The main chronicle on Edward’s reign, commissioned by Edith herself, actually attempts to discredit Harold’s claim, showing the extent of the rift between the siblings. Some historians, such as James Campbell, even believe that Edith was in personal danger from Harold, who wanted to placate the still restless Northumbrians by treating Edith harshly.

Harold successfully fought off Norwegian invaders that year at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, in which Tostig died fighting on the side of the Norwegians. Edith’s reaction is not recorded, but it is easy to imagine that she must have been heartbroken. Harold’s next major battle, the Battle of Hastings, was fought against William, Duke of Normandy. Harold and 2 of Edith’s other brothers died that day, and William was proclaimed King.

William sent men to Winchester to demand tribute from Queen Edith and she willingly complied. As a result, William allowed her to keep all her estates and income. Following this, Edith lived a comfortable life and when she died on 18 December 1075, she was recorded as the richest woman in England. She was laid to rest next to her husband in Winchester Cathedral and given a funeral befitting a queen.

As with so many women in history, Edith is often overlooked, but we have much to thank her for. Because she commissioned the Vita Edwardi Regis, she is responsible for much of the information we have on this period, and art historian Carola Hicks even suggests that she commissioned the Bayeaux Tapestry. Regardless of whether this theory is true, Edith is a person worth remembering. She was strong, determined, and loving, though some of her more corrupt actions are utterly deplorable. Nonetheless, her influence and contribution to Edward the Confessor’s reign is not one that should be forgotten.

Post link

Fredegund

Queen Consort of Neustria (western Francia)

Born ? - Died 597 CE

Claim to Fame: A brutal and formidable queen, best know for her forty year feud with her sister-in-law, Queen Brunhild of Austrasia.

Background: High-ranking women in Merovingian Gaul could hold substantial wealth and status in the fifth and sixth centuries which enabled them to exercise significant social, political and religious influence.

Born into a low-ranking family, Fredegund was a servant to the first wife of King Chilperic I of Neustria, Audovera. She seduced Chilperic and convinced him to divorce and expel Audovera. Chilperic then married a wealthy second wife, Galsuenda, but she soon died and was swiftly replaced as queen by Fredegund. Stories of Galsuenda’s death vary but it is believed that she spoke out against the immorality of Chilperic’s court so the King and his favourite mistress, Fredegund, had her strangled in bed. The powerful Queen Brunhild of Austrasia was both the sister-in-law of Chilperic (she was married to his brother) and the sister of Galsuenda. Brunhild’s fury at her sister’s death sparked a feud between the once unified houses of Austrasia and Neustria that spanned over forty years. The rivalry between Brunhild and Fredegund was particularly bitter and lead their families through generations of conflict.

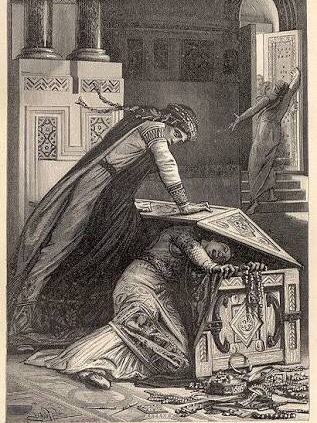

Fredegund is represented in primary sources as a particularly violent woman who used her desirability to manipulate and corrupt those around her. She frequently contracted assassins as well as torturing, maiming and killing opponents. Among her many alleged misdeeds, Fredegund was suspected of ordering the assassination of Brunhild’s husband, Sigebert I, and attempting to assassinate Brunhild’s son Childebert II, her brother-in-law Guntram of Burgundy, and even Brunhild herself. In a jealous rage, she even attempted to murder her own daughter, Rigunth, by slamming the lid of a chest down on her neck as she reached for the jewelry inside. However, her violence was not limited to royal family members, and included a number of officials, clergymen and locals. In a classic example, Fredegund attempted to quell a dispute between kinsmen but ‘when she failed to reconcile them with gentle words she tamed them on both sides with the ax’ by inviting them to a feast and having them all murdered. Her formidable reputation served her well and she manipulated all levels of society through the fear of her fury.

When a dysentery epidemic struck her husband and two of her sons in 580 CE, Fredegund was plunged into remorse. Believing the epidemic was punishment for her sins, she burned unfair tax records and donated to the church and the poor after her sons succumbed to the disease.

In 584 CE, her husband, Chilperic, was mysteriously assassinated and Fredegund sought refuge in the Notre Dame de Paris cathedral. She died of natural causes 8 December 597 in Paris and is entombed in Saint Denis Basilica.

Several years after Fredegund’s death, her son Clothar II defeated Brunhild in battle and, despite the Queen being in her late sixties, he had her stretched on the rack for three days and then torn apart by four horses. Such was the bitterness of their familial enmity.

Note: The main source for Fredegund’s life is Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks. Gregory was patronised by Queen Brunhild so his depictions of her qualities and the evils of her rival, Fredegund, are likely biased. Other sources recognise Fredegund’s brutality but treat her and Brunhild more equitably.

~ Much of this mini-bio is based on an essay of mine, so please PM me for sources.

Post link

A poor quality image but I still love this one of women sewing a corpse into a shroud from a 15th century book of hours. Preparing and shrouding the corpse was traditionally the role of women in Western culture until the late 19th/early 20th century.

Ah how I love the Trotula!

——————

On excessive flux of the menses

29. Sometimes the menses abound beyond what is natural, which has happened because the veins of the womb are wide and open, or because sometimes they break open and the blood flows in great quantity. And the flowing blood looks red and clear, because a lot of blood is generated from an abundance of food and drink; this blood, when it is not able to be contained within the vessels, erupts out.

31. The cure. If, therefore, the blood is the cause, let it be bled off from the hand or the arm where the blood is provoked upward. Any sort of gentle cathartic ought also to be taken.

34. Let her eat hens cooked in pastry, fresh fish cooked in vinegar, and barley bread. Let her drink a decoction made from barley, in which great plantain root is first cooked, and boil it with the decoction and it will be even better. And afterward boil [the root] in seawater until it cracks and becomes wrinkled, and let vinegar be added and let it be strained through a cloth and let it be given to drink. Let her drink red wine diluted with seawater. And if great plantain root is boiled with the decoction, so much the better.

43. In another fashion, take shells of walnut and make a powder and give it in a drink with seawater. Then make a plaster of the dung of birds or of a cat [mixed] with animal grease and let it be placed upon the belly and loins.

—————

From ‘Women’s Lives in Medieval Europe : A Sourcebook’ edited by Emilie Amt (Taylor & Francis Group, 2010).

“There were once women in Denmark who dressed themselves to look like men and spent almost every minute cultivating soldiers’ skills; they did not want the sinews of their valor to lose tautness and be infected by self-indulgence. Loathing a dainty style of living, they would harden body and mind with toil and endurance, rejecting the fickle pliancy of girls and compelling their womanish spirits to act with a virile ruthlessness. They courted military celebrity so earnestly that you would have guessed they had unsexed themselves. Those especially who had forceful personalities or were tall and elegant, embarked on this way of life. As if they were forgetful of their true selves they put toughness before allure, aimed at conflicts instead of kisses, tasted blood, not lips, sought the clash of arms rather than the arm’s embrace, fitted to weapons hands which should have been weaving, desired not the couch but the kill, and those they could have appeased with looks they attacked with lances.”

~ Saxo Grammaticus in Gesta Danorum c1200 CE

Some interesting tidbits on the penalties for cross-cultural sex in 13th century Spain from ‘The Crusades: A Reader’, edited by S.J. Allen and Emilie Amt.

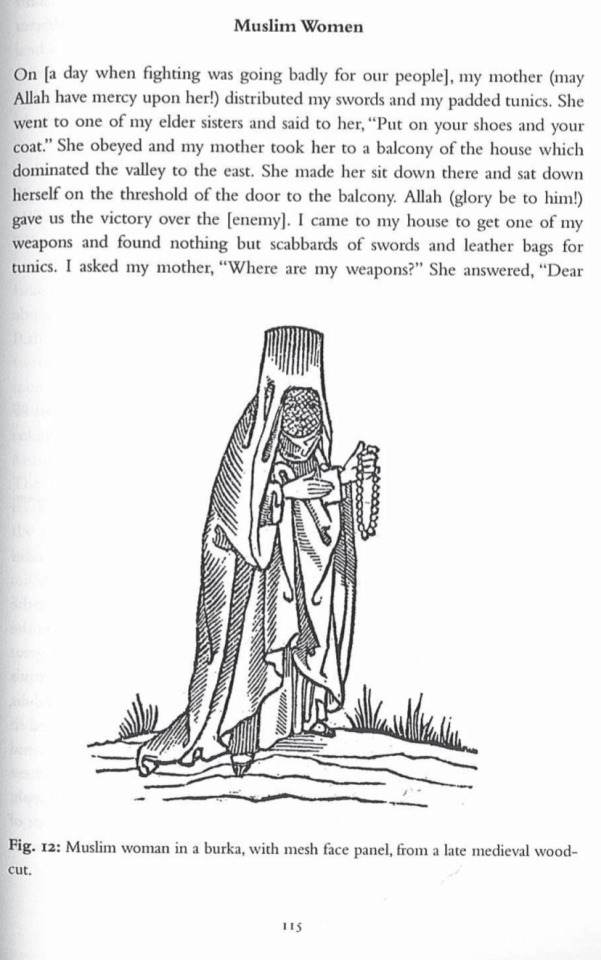

An interesting segment on medieval Muslim women from the Memoirs of Usamah Ibn Munqidh in ‘The Crusades: A Reader’, edited by S.J. Allen and Emilie Amt

I love the feisty old woman! ✊

“Duke Amalo sent his wife to another estate to attend to his interests, and fell in love with a certain free-born girl. And hen it was night and Amalo was drunk with wine he sent his men to seize the girl and bring her to his bed. She resisted and they brought her by force to his house, slapping her, and she was stained by a torrent of blood that ran from her nose. And even the bed of the duke mentioned above was made bloody by the stream. And he beat her, too, striking with his fists and cuffing her and beating her otherwise, and took her in his arms, but he was immediately overwhelmed with drowsiness and went to sleep. And she reached her hand over the man’s head and found his sword and drew it, and like Judith Holofernes struck the duke’s head a powerful blow. He cried out and his slaves came quickly. But when they wished to kill her he called out saying: “I beg you do not do it for it was I who did wrong in attempting to violate her chastity. Let her not perish for striving to keep her honor.” Saying this he died. And while the household was assembled weeping over him the the girl escaped from the house by God’s help and went in the night to the city of Chalon about thirtyfive miles away; and there she entered the church of Saint Marcellus and threw herself at the king’s feet and told all she had endured. Then the king was merciful and not only gave her her life but commanded that an order be given that she should be placed under his protection and should not suffer harm from any kinsman of the dead man. Moreover we know that by God’s help the girl’s chastity was not in any way violated by her savage ravisher.”

~ Gregory of Tours

Historia FrancorumIX:27,6th century CE

Isabella of Angoulême

Queen consort of England and Countess of Angoulême

Born c. 1186/c. 1188 - died 1246

Claim to fame: a feisty young queen who defied the English monarchy and rebelled against the French.

At the age of 12 or 14, Isabella became the second wife of 34 year old King John of England in 1200. Though young, she was already a renowned beauty with blonde hair and blue eyes. It was reported by his critics that John was so infatuated with her that he neglected his duties as king to stay in bed with her. She became the Countess of Angoulême in her own right in 1202. She had five children with John, including his heir Henry III. She oversaw the coronation of Henry after John’s death in 1216 but left her son and returned to France a year later although he was just nine years old.

In 1220 Isabella married Hugh X of Lusignan, Count of La Marche. Interestingly, she had been betrothed to his father prior to her marriage to John and Hugh X was engaged to her daughter, Joan, but decided he preferred Isabella who was still still a beautiful woman of around 30 years old. She married without the consent of Henry III’s council which lead to a stoush whereby her dower lands were confiscated and she threatened to prevent the marriage of her daughter to the King of Scots. Her son tried to have her excommunicated but eventually came to terms. She had a further nine children with Hugh.

Apparently disgruntled with her lower status as countess, she took great offence to being publicly snubbed by the French Queen Dowager, Blanche of Castile, whom she already hated due to her support of the French invasion of England in 1216. In retaliation, Isabella reportedly conspired with other disgruntled nobles to form an English-backed confederacy against the French King Louis IX. By 1244 the confederacy had failed but Isabella was implicated in an attempt to poison Louis. To avoid arrest she fled to Fontevraud Abbey where she died two years later.

The first image is of her effigy at Fontevraud Abbey. The second is her seal, presumably designed before she had fourteen children…

My “Almost Queens” blog series takes a look at some of the girls and women who nearly became Queen (generally consort), had fate not intervened.

Margaret of Burgundy was almost a Queen of France. But the discovery of her affair with a knight from her father-in-law’s court saw her imprisoned in Chateau Gaillard, and possibly murdered on the orders of her cuckolded husband.

Find out more at The Creative Historian.

Reblogging as she died on this day (30th April) in 1315!

Post link

“One poignant expense in [Elizabeth of York]’s Privy Purse is tiny: 3½ yards of cloth to “a woman that was nurse to the Prince, brother to the Queen’s grace.” Nineteen years after the young prince disappeared, his older sister remembered the nurse who took care of him. Similarly, she regularly sent alms to “a poor man” who was a former servant of Edward IV.”—Arlene Okerlund,Elizabeth of York: Queenship and Power(viarichmond-rex)