#11th century

Uta von Ballenstedt

Margravine of Meissen

Born c. 1000 — Died pre-1046

Uta was a member of the House of Ascania. Through her marriage to Margrave Eckard II, she was the Margravine of Meissen in Saxony, eastern Germany.

Presumably to promote the rise of the Ascanian dynasty, Uta’s father married her to Eckard II in about 1026. However, the marriage produced no children, resulting in the extinction of the Ekkeharding dynasty.

The couple contributed a significant amount to construct what would become the Naumburg Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul.

When the Cathedral was completed in the mid-13th century, the presiding bishop honoured the founders, Ekkehard, Uta and 10 other nobles by commissioning the anonymous ‘Naumburg Master’ to produce life-size painted statues of them to adorn the cathedral. The sculptures are remarkable as secular rather than biblical decorations for the cathedral, particularly as they depict nobles rather than kings or emperors. The depictions are now generally considered masterpieces of Gothic art.

In the 20th century, the statue of Uta was used by the Nazi’s as a prototype of the ideal Aryan woman, even appearing as an Aryan role model in Fritz Hippler’s propaganda film The Eternal Jew.

It is also believed that the statue inspired the depiction of the Evil Queen in Disney’s 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. You be the judge!

NB: the dates from when her image was used to depict a ‘Teutonic Madonna’ in various Nazi propaganda makes me wonder if that was why her likeness was used to represent an evil character in the Disney film. Just a thought!Post link

The nobility of your forbears magnified you, O Edith,

And you, a king’s bride, magnify your forbears.

Much beauty and much wisdom were yours

And also probity together with sobriety.

You teach the stars, measuring, arithmetic, the art of the lyre,

The ways of learning and grammar.

An understanding of rhetoric allowed you to pour out speeches,

And moral rectitude informs your tongue – Godfrey of Cambrai, prior of Winchester Cathedral (1082-1107)Edith of Wessex was born c. 1025, the eldest daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and his wife Gytha. Her family was a formidable one: Godwin was one of the most powerful men in England, while Gytha was the sister-in-law of Cnut.

She was raised at Wilton Abbey, which she later had rebuilt as a sign of gratitude. There she learned Latin, French, Danish, and some Irish as well as grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, weaving, embroidery, and astronomy. There is little else we know about her early life apart from her education, but she seems to have been especially close to her brother Tostig.

Edith’s father, Godwin, had a troubled relationship with King Edward the Confessor because Edward believed that Godwin was responsible for the death of his brother. Even so, Godwin was the most powerful man in England and Edward needed his support, and so married Edith at Godwin’s behest on 23 January 1045.

The relationship does not seem to have been a particularly romantic one. They were 20 or so years apart in age and he disliked her family, but all the same she had some influence and it was said that she always advised Edward wisely, and did a lot to improve his kingly image.

In 1051, Godwin and Edward’s relationship significantly deteriorated. Rather than risk arrest, Godwin fled the country with his sons. Edith was sent to a nunnery and all her lands confiscated, perhaps because he didn’t like her, thought they had little hope of conceiving together and wished to remarry, or simply wanted to get revenge on her father. The next year Godwin returned to England and civil war looked likely, but Edward lacked support and was forced to restore Godwin’s lands to him and reinstate Edith as Queen.

Though the two were still unable to have children (probably not because Edward had taken a vow of chastity, as is often said), Edith’s influence as Queen grew, as is shown by the increase in the amount of charters she witnessed, and she joined the circle of Edward’s most trusted advisers.

In 1055, Edith’s brother, Tostig, became Earl of Northumbria but his rule was hugely unpopular and 10 years later the local Northumbrian population rebelled, killing Tostig’s officials and outlawing him, asking instead to be ruled by a member of the leading Mercian family. There is some evidence that many of the Northumbrian people viewed Edith as complicit in Tostig’s tyranny, and indeed it’s likely that she herself had one of Tostig’s political enemies assassinated. Finally, one of Edith’s other brothers, Harold was sent to deal with the matter. He agreed to the rebels demands, depriving Tostig of his earldom, and Tostig, who fled to Flanders, never forgave Harold, nor did Edith.

On 5 January 1066, Edward the Confessor died, leaving Edith’s brother as King Harold II. The main chronicle on Edward’s reign, commissioned by Edith herself, actually attempts to discredit Harold’s claim, showing the extent of the rift between the siblings. Some historians, such as James Campbell, even believe that Edith was in personal danger from Harold, who wanted to placate the still restless Northumbrians by treating Edith harshly.

Harold successfully fought off Norwegian invaders that year at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, in which Tostig died fighting on the side of the Norwegians. Edith’s reaction is not recorded, but it is easy to imagine that she must have been heartbroken. Harold’s next major battle, the Battle of Hastings, was fought against William, Duke of Normandy. Harold and 2 of Edith’s other brothers died that day, and William was proclaimed King.

William sent men to Winchester to demand tribute from Queen Edith and she willingly complied. As a result, William allowed her to keep all her estates and income. Following this, Edith lived a comfortable life and when she died on 18 December 1075, she was recorded as the richest woman in England. She was laid to rest next to her husband in Winchester Cathedral and given a funeral befitting a queen.

As with so many women in history, Edith is often overlooked, but we have much to thank her for. Because she commissioned the Vita Edwardi Regis, she is responsible for much of the information we have on this period, and art historian Carola Hicks even suggests that she commissioned the Bayeaux Tapestry. Regardless of whether this theory is true, Edith is a person worth remembering. She was strong, determined, and loving, though some of her more corrupt actions are utterly deplorable. Nonetheless, her influence and contribution to Edward the Confessor’s reign is not one that should be forgotten.

Post link

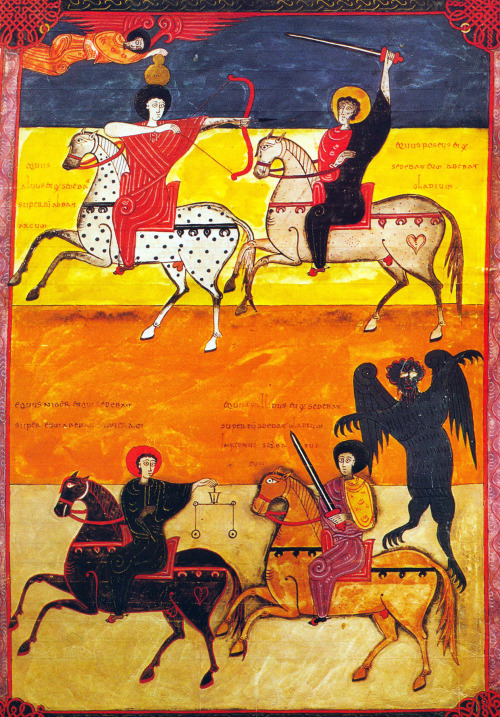

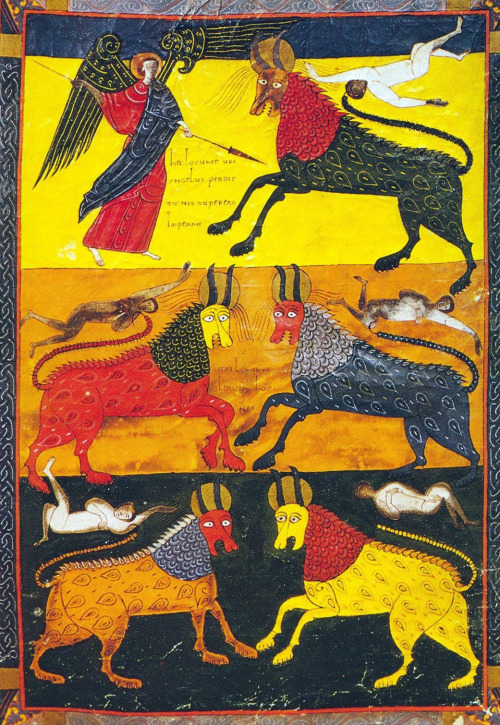

Facundus

Illustrations from a version of the Commentary on the Apocalypse, or the Beatus, c. 1047.

Post link

(From http://ubrus.ru/node/10864, scroll pretty far down.)

Echtra Fergus mac Léti facsimile copy Gaelic manuscript 11th Ct - Copy of 8th Ct text

“This medieval tale "Echtra Fergus mac Léti” (Saga of Fergus son of Léti) contains the earliest known reference to a leprechaun (8th Century). This facsimile copy is on display in Ireland’s National Leprechaun Museum.“

-taken from @nicolekearney & @leprechaun_ie on twitter

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2022/03/echtra-fergus-mac-leti-facsimile-copy.html

Necklace Centerpiece,Attributed to Syria,11th century, Gold & glass, H. 5.8 x W. 3.4 x D. 0.6 cm. x Wt. 11.3 g. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New-York, USA

Historical Objects: St Margaret’s Gospel Book

Saint Margaret of Scotland, queen to King Malcolm III, is probably one of the most famous women in Scottish history, and the country’s only royal saint. As a granddaughter of Edmund Ironside and the sister of Edgar Aetheling, she was an eleventh-century princess of England’s pre-Norman royal family, the House of Wessex, who though she allegedly wished at first to be a nun, ended up marrying the Scottish king c.1070. As queen of Scotland, she is credited with helping revitalise the life of the Church in the country (founding many churches, such as that which later became Dunfermline Abbey, and helping revive interest in things like the shrine of Saint Andrew) as well as bringing the it more in line with the Roman tradition, and also with helping to transform the kingdom in a more secular sense. She was also the mother of three (possibly four) kings of Scotland and one queen of England, as well as being the grandmother, through her two daughters, of the Empress Maud and her rival King Stephen’s wife Queen Matilda of Boulogne. Little wonder, then that she has remained famous and revered as a holy woman since even her own lifetime over nine hundred years ago.

As a girl, Margaret may have spent some time at a nunnery- probably Wilton Abbey, Salisbury- and grew to be a very learned woman. To this end she possessed several books of which only two survive- a psalter in Edinburgh and this Gospel-Book, possibly her favourite of them all, which now resides in the Bodleian at Oxford. After Margaret’s death, the book passed through many different people’s hands, gradually becoming disassociated with its saintly owner, so that, by the late nineteenth century, when it arrived at the Bodleian, having been bought comparatively cheaply and (inaccurately) dated to the fourteenth century. However in 1887 a young woman named Lucy Hill, through the studying of a poem inscribed at the front of the book, realised that what she was holding was nothing other than Saint Margaret’s own Gospel-Book and, happily, brought her findings to light.

But the book is not simply remarkable for having been thought lost for so long. It is also rare in that it is the subject of a particular allegedly miraculous event- in memory of which, the poem was inscribed at the front of the book and, perhaps more importantly, the poem matches up with a story told in the biography of Margaret written by Turgot at the request of her daughter Queen Matilda (or Edith). The story goes that St Margaret’s Gospel-Book (at that time with a cover of jewels and gold, though since replaced with a leather one), whilst being carried on a journey, slipped unnoticed from its holdings and fell into a fast-flowing river. When it was eventually recovered, the onlookers were sure that, with its silk covers washed away, its pages would be completely ruined but in an apparent miracle it was undamaged save for some slight moistening of the edges (and indeed, some water-staining on the manuscript would seem to support the tale). Thereafter, it is said that Margaret cherished it more than before with the result that the book now held by the Bodleian could very well be St Margaret of Scotland’s favourite book.

But even without its miraculous story, the book would still have been extremely precious to its owner. Books were expensive and difficult to make in those days- since there was no paper available in England at the time, the parchment had to be made from animal skin, which had to go through an extremely arduous process before it could be written on. The scribe then would have had a tremendous amount of work to do when he or she came to write it, and the elaborate decoration of the words and pages are also testament to someone’s hard work. And to historians it is doubly precious in that it is a short, selective, Gospel-Book intended to be small and easily carried making it an extremely personal item in contrast to the full versions of the Gospel which Margaret may also have owned. The selections of texts in it tell us a lot about the Queen’s piety- for example, the large number of tales regarding women such as Martha and Mary Magdalene.

Therefore, even if you’re not the type to believe in miracles, the identification and survival of St Margaret’s Gospel-Book is something of a miracle for history in itself- it’s existence gives us, in a way very few other things could, a glimpse into the mind of, and a physical link to, one of Scotland’s most remarkable queens.

* And there were a LOT of remarkable Scottish queens. The picture above is not mine, sorry. It is worth noting that a copy of the Gospel-Book may be found in St Margaret’s Chapel at Edinburgh castle as well. For references, see Richard Oram’s ‘Domination and Lordship’, Rebecca Rushforth’s book on the Gospel-Book, and others.

Post link

The Mysterious Lady Aelfgyva-women in history(42/?)

The Tapestry of Bayeux (Tapisserie de Bayeux) is an impressive embroidered cloth (70 meters long, 50 centimeters tall – 230ft x 20in) and tells the story of the Norman conquest of England by William, duke of Normandy, culminating in the Battle of Hastings (1066). It is thought to be made quite shortly after the conquest, somewhere in the 11th century.

This fragment is the only fragment putting a woman at the center stage. It is one of the most intriguing parts of the tapestry. It portrays a woman confronted by a tonsured cleric, who is touching her face; it is not clear if it is out of anger or affection. Above the scene, the inscription reads: Ubi unus clericus et Aelfgyva - Here a certain clerk and Aelfgyva. Since it is the only part of the tapestry that shows a woman on the center stage, and one of the few women on the tapestry, her role in the episode must have been viewed by the artist as significant.

Historians are unsure about who this woman is. Often it is thought she is queen Aelfgifu-Emma, the mother of King Edward the Confessor. Other historians, like Freeman, state that Harold might have had a sister, who accompanied him in his ill-fated mission. More recently, it has been argued she is Aelfgifu of Northampton, mistress of Canute the Great and mother of his sons.

The story of Aelfgyva is an example of how women are often forgotten and lost in history: overlooked in stories of men, their agency taken away. As Gloria Steinman said: Women have always been an equal part of the past. We just haven’t been a part of history.

McNulty, J. Bard. “The Lady Aelfgyva in the Bayeux Tapestry.” Speculum, vol. 55, no. 4, 1980, pp. 659–668.

St. Georg, Reichenau, Germany, 11th century (church dates back to the 9th century)

Photos:Allie_Caulfield (2 photos at the top) / See58 (photo at the bottom)

Post link

Left: Illustration of a man wearing herigaut ca. 1280-1285.

Right: Dress from Michael Kors Spring 2005 Ready-To-Wear collection.

Post link

![esmitierra:Hermitage of Santo Cristo, Coruña del Conde, Burgos, Castile and León, Spain. VIA. [x] esmitierra:Hermitage of Santo Cristo, Coruña del Conde, Burgos, Castile and León, Spain. VIA. [x]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/35943198c599fcc0d476641f72105899/tumblr_oz02aaQfWI1tsl05ao1_500.jpg)