#meganeura

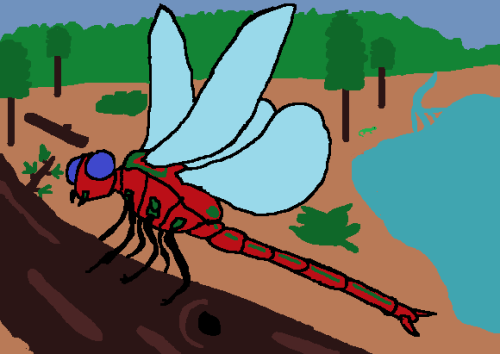

Paisagem do período carbonífero, com uma Meganeura e alguns anfíbios.

Carboniferous period scene, featuring a Meganeura and some amphibians.

Ludek Pesek.

Post link

Meganeura – Late Carboniferous (305-299 Ma)

Remember a while ago, when I talked about big Carboniferous arthropods, and then proceeded to talk about a tiny one? And then at the end, promised to talk about the big ones ‘soon’? Well, it’s finally time. This is one of my favorite insects of all time, and one that was really, really fun to draw.

Meganeura, (‘large nerve,’) was one of the biggest flying insects ever. Its wingspan ranged from 25-28 inches (65-70 centimeters). This is an insect the size of a crow, as David from the Common Descent Podcast put it. It’s a member of a clade called Meganisoptera, or griffinflies, and are closely-related to dragonflies and mayflies. Meganeura is an unusually well-preserved insect. Its name comes from the fact that several of its fossils clearly shows the veins of its wings. This is what we paleoinvertebrate enthusiasts call a Big Deal™. And look at the detail of those segments, and even the head, which is unusual for Meganisopteran fossils.

I discussed this the last time I talked about a Carboniferous arthropod, but the Carboniferous and very early Permian are the only time insects got this huge. Afterwards, they never got quite this big again. That’s likely because the Carboniferous atmosphere contained around 33% oxygen content, whereas now it’s only 21%. Arthropods have no lungs. Air flows through openings in their body called spiracles, and is then carried through their respiratory system and distributed through the body directly. The movement of the different segments of their body also helps move oxygen. They don’t inhale or exhale, and they don’t have blood as we know it. It doesn’t carry oxygen, and functions more like our lymphatic fluid.

If this sounds dumb and impractical, it’s actually way more efficient for small animals. It’s a lot less effort than active respiration. Small vertebrates are always breathing so quickly, but arthropods are just fine. The downside is, they can only get so big, since they need a certain amount of ambient oxygen or they just can’t breathe. But the Carboniferous offered exactly that, and thusly, we have monstrosities like Meganeura and its pals.

There is some controversy to this idea, though. Similarly-sized Meganisopterans lived into the Permian, when the oxygen content appears to be much closer to that of today. Scientists also point to a lack of flying vertebrates, giving insects license to party in the sky.

This was a predatory insect, if ever there was one. It ate other insects for the most part, but also ate small amphibians and reptiles if it could get ahold of them. The key phrase there is, “if it could get ahold of them.” Although its living cousins are speedy little fighter jets who can quickly zip and weave, Meganeura was a slower, more powerful ambush hunter. Its eyes were similar in shape to those of modern Hawker dragonflies, which hunt by watching the air overhead and leaping from its perch to snatch flying prey. They were adapted more for hunting in open areas, rather than the dense undergrowth so characteristic of the Carboniferous.

These wings were powerful—modern dragonflies and mayflies fly with what’s called direct flight. This means they have muscles attached directly to their wings, whereas plenty of other insects fly by flexing their bodies to indirectly move their wings. Meganeura probably moved its wings like dragonflies, and that probably allowed it to get so big while retaining its flight and lifestyle. We don’t know for sure how quickly it beat its wings, but they may have sounded something like this.

In summary, this was an insect that acted a lot like a dragonfly, only gigantic. It was a dragonfly that could eat lizards, and whose nymphs were active hunters of small fish and amphibians. This backwards world, where bugs eat fish and are the biggest terrestrial organisms, is part of what makes paleontology so exciting. Everything about Meganeura reads like a description of a sci-fi monster. This is a huge part of why I love the Paleozoic so much, too. It was the slow windup to modern conventions and ecosystems, and in the meantime, pretty much anything went. Bugs could be giant apex predators, and that was just fine.

Also, I did base its color scheme off Yanma and Yanmega, which are two of my favorite Pokemon.

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link