#paleozoic

I had a lot of fun with those Permian drawings, so I decided to do another quick set of designs for my red bubble! Link will be in a reblog. If you’d like other flags or flag combos, just ask!

[ID: Several versions of the same drawing, showing two cartoony Opabinia facing each other. They are aquatic arthropods with segmented bodies with fin-like appendages, five eyes, and a single long facial appendage with a grasper at the end. The two are forming a heart shape with their curved facial appendages. Cursive text above them reads, “Gaymbrian Period.” In each image, the animals’ segments are colored with the colors of a different pride flag. In the first, one is the color of the original 9-stripe gay flag, while the other is trans flag colors. There are also two in gay flag colors, two in pan colors, two in bi colors, and two in lesbian colors. End ID.]

Dinosunday

Irritator

Temporal Range: Early Cretaceous, 110 Ma

Location: South America

Diet: Omnivore

Family: Spinosauridae

Strataday

Saltatelli F. “Triassic Layering in Ischigualasto Provincial Park,” Valley of the Moon. San Juan, Argentina.

Cotylorhynchus

Fossil specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History

Reconstruction by Hirokazu Tokugawa

When: Permian (~299 to 265 million years ago)

Where: North America

What: Cotylorhynchus is a member of one of the most basal groups of synapsids, the Caseidae. Cotylorhynchus was a herbivore, and reached lengths of up to 20 feet (~6 meters) long, with a massive barrel chest, putting weight estimates at around 2 tons. This animal is very large for its time… well at least its body is. Cotylorhynchus has one of the most extreme cases of ‘tiny head’ I have ever seen. Even more so than the sail-backed Edaphaosaurus! Which is closer to modern mammals than Cotylorhynchus is. It is one of the most primitive animals known that unambiguously falls on the synapsid lineage. It is so basal that it does not even have any differentiation seen in its dentition, though there are less teeth than found in the non synapsid contemporaries of this wee-headed creature.

Post link

Louisella

Reconstruction by Marianne Collins

When: Cambrian (~505 million years ago)

Where: British Columbia, Canada

What: Louisella is a worm-type organism from the Burgess Shale formation in the Canadian Rockies of BC. This organism was about 12 inches (~30 centimeters) long, with a proboscis at its anterior end that could be inverted into the body or extruded. In the images above it is inverted into the body in the fossil specimen, but shown at its full extended length in the reconstruction. This structure was ringed by a series of spines with shorter and more robust spikes on the end of the proboscis. These structures would rub past one another as the animal extended and retracted its proboscis, allowing it to ‘chew’ its food. The rows of short fringes on one surface of Louisella are thought to possible have been the animal’s gills. This worm has been reconstructed as a burrowing and carnivorous creature, and due to the grinding capability afforded to it by its proboscis, it likely ate animals of a relatively large size.

Louisella is currently held as a stem fossil on the lineage leading to the Priapulida worms, also known as the 'Penis worms’. I swear I am not making that up. These worms are very rare even today, with less than 20 living species known. They, like their ancient relative, are burrowing creatures which hunt other invertebrates. Fossils of priapulid worms are also rare, only a handful of Louisella specimens are known. What is far more common though are their distinctive shaped burrows, which are sort of an interlocking L-shape. The appearance of this type of burrows is one of the biostratigraphic markers of the start of the Cambrian period.

Louisella on the ROM’s amazing Burgess Shale website

Post link

Ophiacodon

Mounted specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC.

Reconstruction by Dmitry Bogdanov

When: Late Carboniferous to Early Permian (~305 - 280 million years ago)

Where: North America

What:Ophiacodon is a basal synapsid, meaning it is more closely related to mammals than modern reptiles. It was a fearsome predator of its day, with a long snout (over half of its skull length) full of pointy teeth. These teeth are so sharp that they are reminicent of the fangs of snakes - the name Ophiacodon means ‘Snake Tooth’. Ophiacodon reached up to 10 feet (~ 3 meters) in length and is thought to have preyed upon its fellow tetrapods rather than insects, as many previous predators focused on.

Ophiacodon occurs very early in synapsid evolutionary history, it is even more basal than the ’sailbacks’; almost at the base of the spilt between the major living aminote clades. Ophiacodon is part of the group Ophiacodontidae, which ranged from Mid Carboniferous to the Early Permian. About a half dozen genera are known for this group, and they all were good sized predators. Ophiacodontids and other basal synapsid clades were once grouped together under the name pelycosaurs, however, this group is not monophyletic/a natural group. That means that some synapsids that were held as pelycosaurs are more closely related to mammals than they are to other 'pelycosaurs’. 'Pelycosaurs’ can be though of as an evolutionary grade in the synapsid lineage; these are the members of our group that more closely resemble reptiles - they had sprawling gaits and their their teeth were not differentiated - there is not even a distinct canine. Ophiacodon and its kin are assuredly synapsids, however, as shown by the single opening behind their eye sockets - their single temporal fenestra.

Post link

Gemuendina

Fossil and model both on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Model created by Louis Ferraglio

When: Early Devonian (~410 to 392 million years ago)

Where: Germany

What: Gemuendina is an odd little placoderm fish. It is known only from the early Devonian of Germany, from deposits that have been reconstructed to represent areas with anoxic bottom waters. Anoxic means ‘lack of oxygen’, so there was no oxygen in the sediments where the dead or dying fish fell, and thus scavengers and decomposing organisms could not disturb the remains. Specimens of Gemuendina have only been preserved in such conditions because their armor was not a solid shield, as seen in some other placoderms, but rather a series of unfused relatively thin bony plates. This placoderm bears a close resemblance to a ray, with its flat body and series of horizontal fins. This is another excellent example of convergent evolution. Unlike rays, however, the eyes of Gemuendina were on the top of its head, not the side, and its nostrils were on top as well, not on its ventral (under) surface.

Within Placodermi Gemuendina falls into the clade Rhenanida. This group shares the characters of a ray-like body and the lose series of unfused plates that covered their flat bodies. While the ray-like body is a shared derived feature that unites the group, the seires of individual plates is likely a retained primitive feature that was also found in the first placoderms, which gave rise to all of the rest, including massive forms such as Dunkleosteus. Gemuendina is one of the earliest well-known members of the clade, but isolated plates from tens of millions of years earlier in the Silurian period may represent the true first rhenanids. Though the fossils are rare and fragmentary, rhenanids swam throughout the Devonian waters all over the world.

Post link

Tiktaalik - the fishapod

Model by Tyler Keillor and this particular set up on display at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

When: Late Devonian (~375 million years ago)

Where: Found on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada

What:Tiktaalik is a very critical specimen on the line of tetrapod evolution. In the tetrapod family tree it falls between sarcopterygians (‘lobed fin’ fish) that looked much like the living Coelacanth and more advanced tetrapods, such as Acanthostega.The discovery and announcement of Tiktaalik was very exciting, as fossils on both side of transitional period were known for a long time, but nothing really in the middle. Of course as with the discovery of any 'missing link’ now we have two more 'links missing’: one on either side of Tiktaalik ;). The most important part of the specimen is the anatomy of its forelimb - there was a well developed wrist inside the fin of Tiktaalik! Not only that, but it possibly has the first 'fingers’ seen in the tetrapod lineage. Unfortunately the back end of Tiktaalik is unknown… for now!

In life Tiktaalik would have been an aquatic animal, as its limbs could not support its weight on land - but they would have been very helpful for maneuvering the creature around the shallow waters of prehistoric Canada. Based on the spiracles - openings behind the eyes- of the skull it has been preposed Tiktaalik could have had a form of primitive lung.

If you want to know more about Tiktaalik - check out its website at: http://tiktaalik.uchicago.edu/. And for more in depth reading, I cannot recommend the book 'Your Inner Fish’, written by the discover of Tiktaalik - Neil Shubin, enough! It is a really great explanation of how Tiktaalik fits into the evolution of tetrapods and explaining homology in general! Shubin has done a fantastic job of promoting public science education using this great Tiktaalik specimen as a starting point.

Just look at all of these models getting ready to go out to museums. Maybe one is near you!

Post link

Hybodus

Fossil specimen from the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Germany

Model by Dan Erickson and on display at the American Museum of Natural History

When: Permian to Cretaceous (260 to 80 million years ago)

Where: World Wide

What:Hybodus is a very wide spread, both temporally and geographically, fossil shark. I will be upfront here and say that I may be grossly over representing its temporal range, the literature is rather confusing and there have been a number of species going in and out of Hybodus over the years. So you may want to consider this an article on hybodontiform sharks in general, rather than just the one genus. Shark fossils are fairly rare in the fossil record when compared to other fish because sharks do not ossified their skeleton. However, Hybodus and its kin can be identified from fragmentary remains by their distintive teeth (two kinds in their jaws, both flat and pointy) and their ossified dorsal spines. These spines can be easily seen on both the fossil and the model above, they were most likely involved with stabilization of Hybodus as it swam. The relatively few full body specimens preserved complete the picture, showing us that Hybodus was a streamlined shark with a very heavy ribcage compared to most sharks, and that the males had not only ventral claspers, as seen in modern sharks, but also a series of spines on the side of the head - which are depicted above.

Hybodontiform sharks were the dominate group of sharks in the Jurassic period, and were even very common in the late Cretaceous after modern sharks had originated and diversified. Studies of this archaic shark clade have shown they were most likely over all slow swimmers, but they could enjoy brief bursts of speed if needed. The diverse teeth forms of hybodont sharks imply they did not just eat fish, but also were able to prey on hard shelled invertebrates. In the shark family tree Hybodontiformes is the first group outside of Neoselachii - the clade that contains all living sharks and rays.

Post link

Plesiadapis

Mounted specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Reconstruction by Jay Matternes

When: Late Paleocene to Early Eocene (~ 61 - 55 millon years ago)

Where: North America and Europe

What:Plesiadapis is a small tree-dwelling mammal that was fairly comment in the late Paleocene of North America and Europe. This ancient mammalian taxon was about the size of a house cat, and though it may look very reminiscent of a squirrel it is a member of the primate family, as part of the larger group Plesiadapiformes. The latest research has shown that Plesiadapis was actually atypical for its namesake clade; this genus tended to be much larger than the average plesiadapiform and was not as well adapted for climbing as its smaller relatives, lacking a hand specially adapted for grasping. Plesiadapis could climb trees, but it would have been an arboreal quadruped, like the living squirrels, rather than a grasping locmotion as seen in most primates today. Another features reminiscent of rodents in Plesiadapis (and this is found in most of its kin) is its enlarged front teeth and the reduction or loss of teeth between these massive incisors and the grinding cheek teeth. Plesiadapis has been reconstructed as a frugivore - meaning its diet was primarily comprised of fruit. As much of North America and Europe was covered with lush sub-tropical forests during its range, Plesiadapis would have had quite a large selection of fruits to feed on.

The placement of Plesiadapiformes has been somewhat controversial in the past decade or so. There is uniform agreement that these animals fall somewhere near the group Euarchonta within placental mammals, but exactly where has been much debated. Euarchonta contains not only primates, but also the Scandentia (tree shrews) and Dermoptera (flying lemurs). Some early studies placed plesiadapiforms closer to the dermopterans than primates, but more recent studies tend to find this clade as either the first branches to spring off the primate lineage or just outside of Euarchonta itself, as stem taxa to all three orders. One last point to make things even more confusing! The group Plesiadapiformes? It is probably not a monophyletic (natural) group in reality. It is looking more and more like that some taxa previously grouped within Plesiadapiformes fall closer to living primates than to other taxa within the group.

To sum up that confusing mess, Plesiadapiformes are very important in understanding primate evolution, as at least some members of this assemblage of taxa are the first animals on the primate lineage. As this lineage includes me and you there is a lot of study focused on this group right now! Nice to see animals that are primarily paleocene taxa finally getting some attention.

Post link

Paisagem do período carbonífero, com uma Meganeura e alguns anfíbios.

Carboniferous period scene, featuring a Meganeura and some amphibians.

Ludek Pesek.

Post link

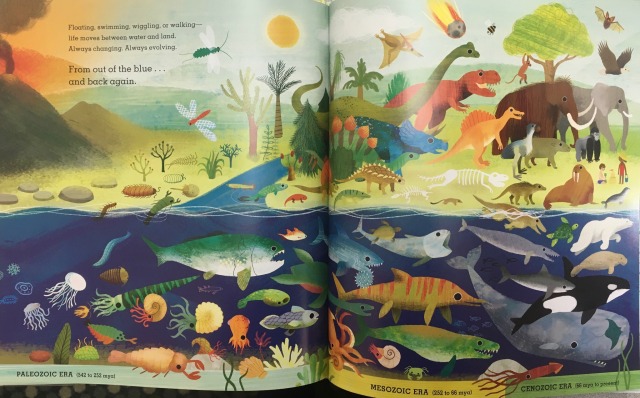

Out of the Blue: How Animals Evolved from Prehistoric Seas final spread

By Elizabeth Shreeve and illustrated by Frann Preston-Gannon

LAST CHANCE to adopt a huggable Permian fossil! https://paleopals.square.site/

Get your prehistoric amphibian pins here: https://paleopals.square.site/#EyzKjP

Snab yours up before they are gone! https://paleopals.square.site/#rTZOwa

Find more Anomalocaris themed goodies at: https://paleopals.square.site/#IShREF

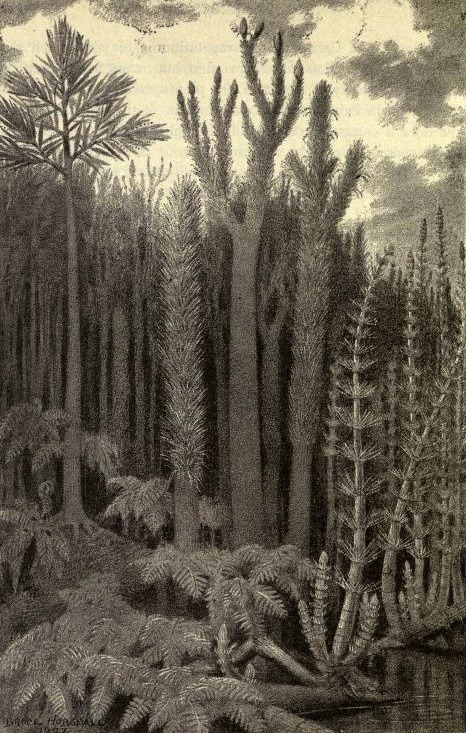

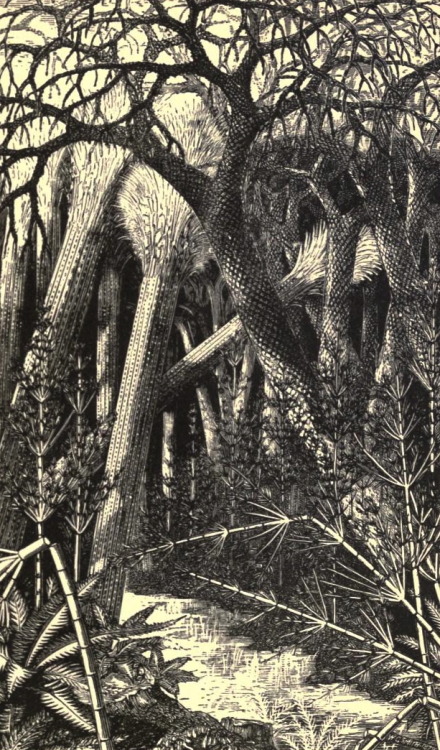

Carboniferous forest scenes by Heinrich Harder, Bruce Horsfall, & W. C. Smith

The Carboniferous is a panoply, an exhibition, a theater of increasing complexity, a demonstration of verdant braggadocio in which amphibians lurk and arthropods achieve hallucinatory measurements. The animals sing and chirp and croak and bellow, splash in the water and feed on each other, they grow and mate and fight and die, but their part in the forest is only a fraction of the symphony here. The green kingdom has its own drama, its own conflicts, kinships, and hymns; it is not passive. Its members also grow and mate and fight and die, but at speeds an animal cannot see and with means an animal cannot notice. Instead of songs, the plants communicate with chemicals—three thousand of them—in a vocabulary unknown and unsensed by eyes and ears, but felt on the tongue when leaves turn bitter or saps run toxic, invisible messages made of methanol, formaldehyde, tannins, caffeine, and terpenoids released into the air to dissuade herbivores, attract plant-eater predators, or alert the forest in a botanic siren that spreads between leaves and branches, roots and buds—a system of communication without sight or sound, where compounds are signals and chemicals are words.

-Benjamin Chandler

Post link