#native women

A RED GIRL’S REASONING : a film by Elle-Maija Tailfeathers starring Jessica Matten

Delia does not pass The Ali Nahdee Test but she is a badass through and through all the same.

“All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans (2016)

“In this enlightening book, scholars and activists Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker tackle a wide range of myths about Native American culture and history that have misinformed generations. Tracing how these ideas evolved, and drawing from history, the authors disrupt long-held and enduring myths such as:

- “Columbus Discovered America”

- “Thanksgiving Proves the Indians Welcomed Pilgrims”

- “Indians Were Savage and Warlike”

- “Europeans Brought Civilization to Backward Indians”

- “The United States Did Not Have a Policy of Genocide”

- “Sports Mascots Honor Native Americans”

- “Most Indians Are on Government Welfare”

- “Indian Casinos Make Them All Rich”

- “Indians Are Naturally Predisposed to Alcohol”

Each chapter deftly shows how these myths are rooted in the fears and prejudice of European settlers and in the larger political agendas of a settler state aimed at acquiring Indigenous land and tied to narratives of erasure and disappearance. Accessibly written and revelatory, “All the Real Indians Died Off” challenges readers to rethink what they have been taught about Native Americans and history.”

byRoxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Dina Gilio-Whitaker

Get it here

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz grew up in rural Oklahoma, the daughter of a tenant farmer and part-Indian mother, and has been active in the international Indigenous movement for more than four decades. She is the author or editor of eight other books, including An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, which was a recipient of the 2015 American Book Award. Dunbar-Ortiz lives in San Francisco.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) is an award-winning journalist and columnist at Indian Country Today Media Network. A writer and researcher in Indigenous studies, she is currently a research associate and associate scholar at the Center for World Indigenous Studies. She lives in San Clemente, CA.

[Follow SuperheroesInColor faceb/instag/twitter/tumblr/pinterest]

Post link

Alice E. Brown was born in 1912 in Kenai, Alaska. Brown worked to defend the rights of Alaska Natives and other marginalized groups in Alaska. She is best remembered for her efforts to pass the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Actwhichat the time of its passage in 1971, was the largest land claims settlement in US history. Brown was also the only woman to serve on the original board of the Alaska Federation of Natives.

Alice E. Brown died in 1973 at the age of 60.

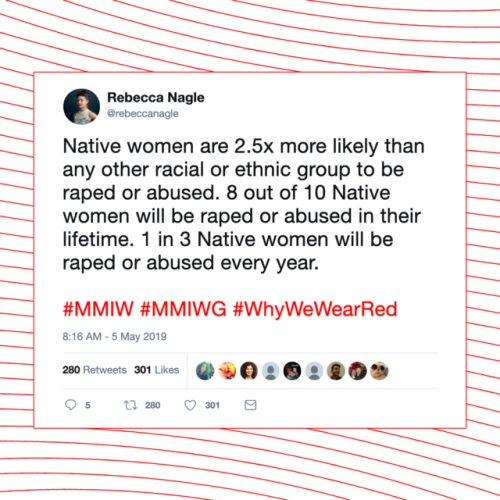

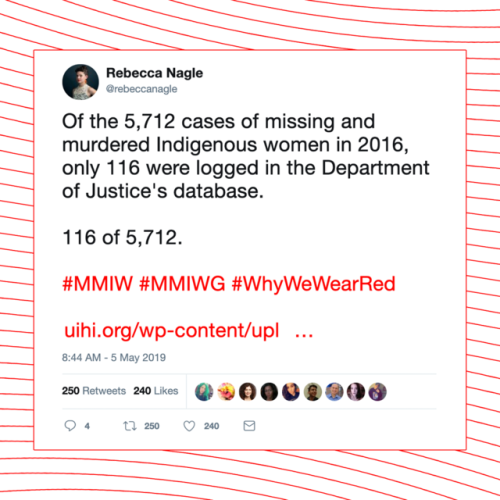

Yesterday was the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, and activists took to Twitter to amplify the stories and stats around this crisis. News outlets should work to bring public awareness to this issue.

The Guardian has started a series called Not Invisible, which seeks to shed light on the violence that Indigenous women face. Other outlets should follow suit in investigating and sharing the stories of Indigenous women.

Post link

Moving Robe Woman - Hunkpapa heroine

Moving Robe Woman (1854-1935) was a Hunkpapa Lakota woman who fought during the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 to avenge her brother.

Moving Robe Woman was harvesting turnips when she heard that her brother had been killed by the U.S. cavalry. According to an interview conducted in 1931 she did the following thing:

“I sang a death song for my young brother who had been killed. My heart was bad. Revenge! Revenge! For my brother’s death. (…) I ran to a nearby thicket and got my black horse. I painted my face with crimson and braided my black hair. I was mourning. I was a woman, but I was not afraid.

(…)

By this time the soldiers were forming a battle line in the bottom about a half mile away. In another moment I heard a volley of carbines. The bullets shattered tipi poles. Women and children were running away from the gunfire. In the tumult I heard old men and women singing death songs for their warriors who were now ready to attack the soldiers. The enchanting death songs made me brave, although as was a woman. Father led my horse to me and…we galloped toward the soldiers.”

Warrior Rain in the Face recalled that Moving Robe Woman was “pretty as a bird” as she was galloped on her charger, brandishing her brother’s war staff over her head. He said: “always when there’s a woman in charge it causes the warrior to vie with each other to display their valor”.

Moving Robe Woman fought as fiercely as any of the warriors. She killed two of Custer’s troopers: shooting one with her revolver and stabbing the other to death with her knife. She also reportedly shot the badly wounded interpreter Isaiah Dorman. A possible account tells the scene as follow, with him saying:

““Do not kill me, because I will be dead in a short while, anyway.”

The woman said, “If you did not want to be killed, why did you not stay home where you belong and not come to attack us?” The first time she pointed the gun it did not go off, but the second time it killed him.”

The battle ended in Custer’s death and a temporary victory. Moving Robe Woman died in 1935. She concluded her interview by saying:

“In this narrative, I have not boasted of my conquests. I am a woman, but I fought for my people. The white man will never understand the Indian. Eyas Hen La! I have said everything!”

Warrior women of the Little Bighorn:

Bibliography:

“Eagle Elk’s story of the battle of the Little Bighorn”

Hall Alan R., A Man Called Plenty Horses, The Last Warrior of the Great Plains War

Hardoff Richard G., Lakota Recollections of the Custer Fight, New Sources of Indian-military History

Lawson Michael L., Little Bighorn, Winning the Battle, Losing the War

Philbrick Nathaniel, The Last Stand, Custer, Sitting Bull and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

Post link

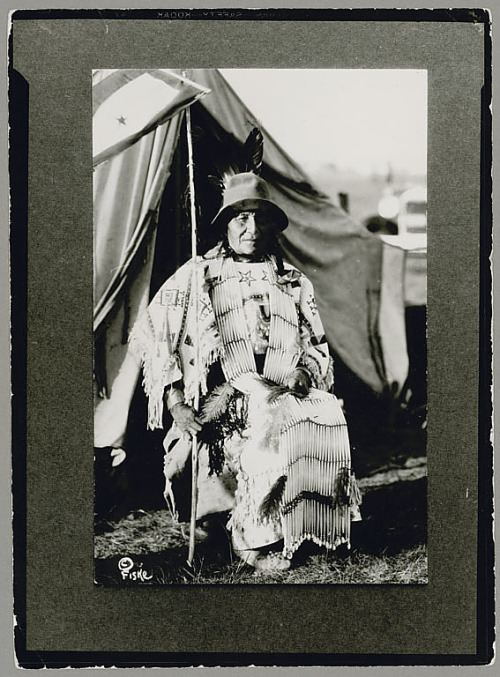

Minnie Hollow Wood and One Who Walks With the Stars - Lakota warriors

Minnie Hollow Wood (c.1856-1930′s) was a Lakota woman and wife to chief Hollow Wood. In 1876, she fought at the battle of Little Bighorn, which ended in a victory of the native tribes against the U.S. army. Minnie distinguished herself when fighting against the U.S. cavalry and was awarded the right to wear a war bonnet.

The tide later turned, and she and her husband surrendered to general Nelson Miles. In 1877, she was among the prisoners at Fort Keogh. She and her husband were later transferred to a reservation where they lived the rest of their lives. The above photograph was taken in 1930 when Minnie Hollow Wood was 74.

Oglala Lakotawoman One Who Walks With the Stars also resisted Custer’s soldiers. She was the wife of Brulé Lakota (or possibly an Oglala) chief Crow Dog. Her story was preserved by survivors of the fight. While her husband didn’t kill anyone during the battle, she killed two soldiers who tried to swim across the river.

Warrior women of Little Big Horn:

Bibliography:

Hirschfeld Arlene, Paulette F. Molin, The Extraordinary Book of Native American Lists

Lawson Michael L., Little Bighorn Winning the Battle, Losing the War

Liberty Margot,”Cheyenne Primacy: The Tribes’ Perspective As Opposed To That Of The United States Army; A Possible Alternative To “The Great Sioux War Of 1876″

Miller Humphrey David, Custer’s fall

Wakim Dennis Yvonne, Native American Almanac More Than 50,000 Years of the Cultures and Histories of Indigenous Peoples

Post link

Nanye’hi “Nancy” Ward - Beloved woman of the Cherokee

Nanye’hi (1738-1822) was a woman the Cherokee nation. In the early 1750s she married a man named Kingfisher. In 1755, she went with him on a military expedition against the neighboring Creeks. Women went with war parties to draw water, gather firewood and cook since male warriors weren’t supposed to perform these tasks due to the separation of gender roles.

During a battle, Nanye’hi hid behind a log, but her husband was shot and killed. She took his gun and fought on, leading the Cherokee to victory. Though war was technically a male domain, there were still instances of Cherokee women taking arms. During the American Revolution, a Cherokee woman “painted and stripped like a warrior and armed with bows and arrows” was found dead on the battlefield. During the same period, another woman slew her husband’s killer on the battlefield and was allowed to join the warriors in the war dance carrying her gun and tomahawk.

In the early 19th century, missionary John Gambold met an old woman named Chicouhla who had “gone to war against hostile Indians and suffered several wounds”. A woman namedCuhtahlatahrallied the warriors after her husband was killed in defending the village. She took his tomahawk, shouted “Kill, kill!” and lead her people to victory. In the 1880s a Cherokee woman whose name meant” “Sharp Warrior” was active.

Nanye’hi was rewarded for her heroism and granted the title of Agigaue,which translates as “Beloved Woman” or “War Woman”. There was, for instance, a “War Woman’s creek”, commemorating the stratagem of a woman who had led her people to victory and was after rewarded with a chiefly position.

Women like Nanye’hi were indeed influential and powerful. Their words were listened to and they were the head of the Women’s Council, involving representatives from each clan. Nanye’hi could also seat at the council of Chiefs. Agigaue also participated in martial dances and prepared the “Black Drink” that was given to the warriors who were about to go on the warpath. She had a right to spare prisoners who had been sentenced to death and in 1776 saved a white woman named Mrs. Bean. In 1781, she and other women helped five traders to escape to safety.

In the late 1750′s, Nanye’hi married white traded Bryant Ward and anglicized her name as Nancy. They had a daughter together named Elizabeth. Before 1760, he returned to live with his other family and Elizabeth remained with her mother. Nanye’hi didn’t, however, completely sever ties with him and sometimes visited him.

During the American Revolution, Nanye’hi sided with the new United States, a rare position among the Cherokee. In 1776, she warned settlers of an impending Cherokee attack. It seems that her decisions came from pragmatism, as she was aware of the superiority of the settler’s superiority in numbers and weapons. In October 1776 Colonel William Christian led a devastating raid on Cherokee territory, but spared Nanye’hi’s town of Chote out of respect for her. Chote was nonetheless destroyed in 1781, Nanye’hi was taken into custody, but was later allowed to leave to rebuild the town.

In 1781, Nanye’hi appeared at her a treaty conference with United States commissioners held on the Long Island. There had been cases before her of Cherokee women serving as ambassadors. She said:

“You know that women are always looked upon as nothing; but we are our mothers and you are our sons. Our cry is all for peace; let it continue. This peace must last forever. Let your women’s sons be ours; our sons be yours. Let your women hear our words.”

Her plight was heard. The original demands were revised and the Cherokee only had to give their land north of the Nolichucky River instead of giving all their lands north of the Little Tennessee River. She called for peace again in 1785, but this time the Cherokee had to cede more lands.

In the 19th century, the Cherokee government system was changing and there was less and less place for a woman like the aging Nanye’hi. United States agents who tried to “civilize” the Cherokee by imposing their values and the statues of women in the nation began to decline. In 1819, her town was ceded and she had to leave with her retinue for the Ocoee River near the present town of Benton, where she ran a sort of inn for travelers. She died in 1822. She thus didn’t live to see her people’s exile on the Trail of Tears following the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

Bibliography:

Harris McClary Ben, “Nancy Ward: The Last Beloved Woman of the Cherokees”

Perdue Theda, “Nancy Ward”, in: Glinton Catherine G. (ed.), Portraits of American Women from Settlement to the Present

Post link