#women warriors

Sketchbook dump! I’ve built up a bit of a backlog because I’ve been working a lot of overtime the past couple weeks.

All of these are original characters from different head worlds of mine. Curious about any of them? Feel free to ask.

Pencil and brush-tip ink pens. I have plans to try to digitally color some of these, but we’ll see if that ever happens.

Post link

Ukrainians will understand…

December 2021

Agnieszka: Join the army? What, me? Are you crazy?

February 2022

Agnieszka: Give me that Javelin!

Post link

These two badass women…

Frau hair/Kylie hair by us. Outfits and weapons by @plazasims,@studio-k-creation and Razon. Amazing skin by @thisisthemand@ba-kalia!

Post link

Xania now regrets all the teasing and realises she may have pushed Melissa too far. As the winner Melissa now gets to wear the crown for the day. As queen she also decides a rather strange punishment for Xania.

Post link

What if I told you anime’s fierce female fighters had their inspiration in real life history? It’s not only the Strike Witches, but real ladies from the past, who have fought for Japan.

Military historian and Anime Boston convention panelist Haru Menna regaled his audience with tales of onna-bugeisha, female martial artists, from Japanese history. Here are five of the most famous, and the shocking exploits we still remember them for today.

Tomoe Gozen

Dubbed Japan’s “Beautiful Samurai,” Tomoe was born in 1184. The Heike Monogatari accounts her exploits, including the final battle she was ever involved with, in which she was the only survivor. Legend has it the only man she couldn’t kill, she married instead. In modern times, she is depicted yearly in the Jidai Matsuri parade in Kyoto.

Tsuruhime of Omishima

Born in 1526, Tsuruhime became the chief priest of the local shrine at age 16 after her father, the previous head priest, died. As a Shinto priest, she was the living embodiment of their local god. As a god, it was easy for her to become the local military leader as well, and she led the armed resistance against pirates trying to take over her hometown.

Miyagino and Shinobu

The woman warriors come as a pair! After a drunk samurai on the run, drunk, killed their father, a farmer, the younger sister (Shinobu) brought a word of the murder to her big sister Miyagino, working as a courtesan in Edo. For seven years they searched for the murderer and trained in hand-to-hand combat. After they found him, their local lord approved their request for a legal duel to the death, two on one. It is said that the murderer died… swiftly.

Nakano Takeko

In 1868, the imperial army put Nakano’s hometown, the city of Aizu, under siege. She formed a unit of about 30 teenage girls, known as the Joshigun, to defend the city. They faced off against 100 imperial soldiers with American Spencer rifles, armed only with naginata. When the imperial army saw their opponents were girls, they asked them to come forward so they could be taken prisoner… That’s when the dismembering began. Nakano sliced through six soldiers in a matter of minutes, and took seven bullets before she went down.

— Lauren, AB Staff Blogger

Artist’s depiction of a Sarmatian warrior

Amage was a Sarmatian warrior queen who lived toward the end of the 2nd Century BCE.

Amage was queen of the Sarmatians, an Iranian people who lived in the western region ofScythia on the coast of the Black Sea. According to the Greek strategist Polyaenus, while Amage’s husband, Medosaccus, was officially the Samartian king, Amage deemed him to be an unworthy ruler who abused his power for personal luxury. She took control of the Sarmatian government and military, using her power to build defensive garrisons which she used to defend her lands on multiple occasions.

Her success as a leader made her famous throughout Scythia and led to the neighbouring Chersonesians to ask for her help when they were being threatened by the Crimean Scythians. Amage agreed to the alliance, sending a message to the Scythian king demanding that he leave the Chersonesians in peace. When the king refused she gathered a force of 120 seasoned warriors, equipping them with 3 horses each so they could cover ground quicky. Marching toward the Scythian palace they covered a distance of more than a 100 stades (180 kilometres) in a single night and a day. The swiftness of the attack caught the Scythian forces off guard and they were easily defeated. Personally leading the assault on the palace, Amage broke into the Scythian king’s quarters and killed him along with his entire family save for one of his sons. She installed the boy as the new Scythian ruler, on the condition that Chersonesus would remain free and that the Scythians would never again attack their neighbours.

While little else is recorded of Amage’s rule, Sarmatian women became known for having a prominent role in war and are recorded by Herodotus as fighting in the same clothing as men. Some believe that the exploits of Amage and similar Sarmatian women served as the inspiration for the Greek myth of the Amazons.

Post link

#mulan when xixi said it was late for her nad that the people will accept #mulan but not her it showed the fact that as time

passes and people realize and opt out of social superstitions. people might not hadaccepted xixi at her time but it was different

as the time was different. In Ruth Bader GInsberg’s biograpic movie “on the basis of sex” it was shown that what she thought was

impossible her daughter did it and she only shouted at people on the streets. From women rights to voting rights what women in the

previous era would think it to be impossible not modern people would and that’s the evolution of mindset and society.

(The women of Eger, by Bertalan Székely)

The women of Eger - Victory or death

In June 1552, the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent began a military campaign against the Habsurgs. In the path of the Ottoman troops was Eger Castle, Hungary. Its garrison, consisting of some 1,920 men, faced a vastly superior force of 27,000 troops. Captain Istvan Dobo was determined to fight to the death and a huge black coffin was placed on Eger’s ramparts to signal this commitment.

Among the garrison were around 90 women, 40 of whom were ladies of nobility. The women refused to escape while it was still possible. They, too, wanted to fight.

The Turks first bombarded the walls, but ran out of ammunition on September 29. Close combat ensued as they tried to breach the walls. In addition to nursing the wounded, the women actively repelled the assailants. They poured boiling water onto them and threw burning faggots soaked with tar. The ladies also fought the Turks in hand-to-hand combat.

Tradition has highlighted some of their names: Margit Hommonay, Eufrozina Gyulafy and Mrs. Job Pasky. Katica Dobo, captain Istvan Dobo’s daughter, led the women on the ramparts “her long brown hair streaming from under her helmet”.

The besieged thus repulsed attack after attack and the Turks had to give up. They lifted the siege on October 13, 1552.

The women of Eger were thus remembered across the centuries as an example of determination and resistance.

If you want to support me, here’s the link to my Ko-Fi.

Bibliography:

Hacker Barton, Vining Margaret (ed.), A Companion to Women’s Military History

Leisen Antal, “Eger, women in siege of”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.1

Post link

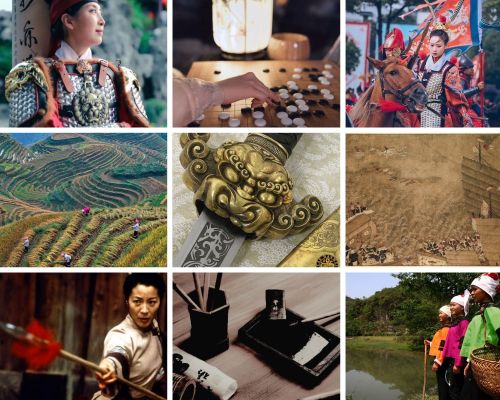

Lady Washi - Ferocious warrior and administrator

Lady Washi (1498-1557) was a woman ofZhuangethnicity. Her father was the sub-prefectoral magistrate of Guishun, present-dayJingxi,Guangxi province, China. She was taught military strategy and martial arts during her childhood.

Lady Washi was married to Chen Meng, the local leader of Tianzhou (present-day Tianyang). In 1523, Chen Meng ignored his wife’s advice and rebelled against the imperial Ming government. He was ultimately killed by Lady Washi’s father. One of Chen Meng’s sons, Chen Bangxiang, took his father’s place, but Lady Washi killed him after he raided her lands.

She then petitioned the court, asking for Chen Meng’s grandson, Chen Zhi, to be allowed to inherit the position and be placed under her care. Her request was granted. Lady Washi thus became regent as Chen Zhi was too young to rule. He died in 1553 and Lady Washi then served as a regent for his son.

She was a talented administrator who had her people’s trust. Lady Washi also proved instrumental in fighting the Japanese pirates who made incursions on the entire eastern seaboard. In 1555, the emperor named her female assistant regional commander. At that time aged of 57, Lady Washi led 5,000 soldiers in battle, killing many pirates, and acquired a reputation as an accomplished warrior.

She thus helped the imperial troops to secure their first victory in this long campaign and her exploits were celebrated by the local people. The emperor awarded her with silver coins.

For another woman who fought against the Japanese pirates, see Lady Qi.

If you want to support me, here’s the link to my Ko-Fi.

Bibliography:

“Lady Washi”, in: Lee Lily Xiao Hong, Wiles Sue (dir.), Biographical dictionary of Chinese women: Tang through Ming (618-1644)

Mou Sherry J., “Wa”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.2

Post link

““Swantepolk, duke of Pomerania, learning of the absence of the (Teutonic Order) brothers and the citizens of Elbing, proceeded there after gathering a great army to attack the fort and town. Seeing this, the women (of Elbing), laying aside feminine adornment, put on a male frame of mind, girded the sword upon the thigh, and ascended the battlements, comporting themselves so manfully for their defence that nowhere was the weakness of their sex apparent. Hence, the duke, thinking that the brothers and townsmen had returned, retreated in fear.Nor should you believe that this only happened here, but (also) many times in other places where in the absence of men the fortifications would have been endangered, if the boldness of the women had not put a resistance.”

Thus Peter of Dusburg, a priest of the military monastic Teutonic Order, depicts an attack on the order’s town of Elbing by the Duke of Pomerania (ally of the Prussian pagans) in 1245. Dusburg’s chronicle, completed in 1326, describes his order’s long crusade against the pagan Old Prussians and Lithuanians (…). Scholars believe Dusburg utilized reports from eyewitnesses and the order’s own oral tradition, since written sources can only be found for only a small part of Dusburg’s section III. The story of the “manly” women of Elbing does not appear in the known sources for his chronicles.

Of course, this leaves the problem of sheer invention by the chronicler to entertain and edify. There is no a priori reason to assume such stories must be invented. Elsewhere in medieval Europe, women did sometime take part in combat, even fighting with sword and lance. We will see that there are story of bellicose women much more factually told in the chronicles of the Teutonic Order and the Order of Sword Brothers in Livonia.

(…)

We have a much more matter-of-fact, first-hand account of women on the battlements in the Baltic wars by Henry of Livonia whose chronicle relating the exploits of the Livonian order of Sword brothers was finished in 1226-1227. (…) Indeed, he was active in the Livonian wars in what is now Latvia and Estonia from 1205 onwards and is thought to have been present at the attack on Riga in 1210 described here:

“Fishermen from all parts of the Daugava River fled to Riga, announcing that (the pagan Curonian) army was following them. The citizens and the brothers of the Order and the crossbowmen, although they were few in numbers with clerics and women all rushed to arms... some of us having brought small three pronged iron nails, scattered these on the road…”

(…)

For the chroniclers of the military orders conducting the Baltic crusade, women in heaven and on earth were not excluded from participation in battle. By definition, there could be no civilians, no bystanders in a war seen as an elemental struggle between God and demons. Women were physically weaker, but God or the Devil could give them strength to become virile at least in their own defense. Probably this partially reflects the reality of life in an area in which the main form of warfare was the raiding party which sought to kill or capture everyone in its path. Women grew up or moved in as colonists to a war zone, and perhaps on some occasion they became warlike. On Christianity’s norther frontier, or at least in the world of its chroniclers, women had equal opportunity to be brave and brutal.”

“”Nowhere was the fragility of their sex apparent”, Women warriors in the Baltic crusade chronicles”, Rasa Mazeika

“As long as you focus on one historical figure, or one cluster of women, or on one historical period, it is easy to believe any individual woman warrior was indeed an exception who stood outside the norm of her time—created by a national crisis or an anomaly of inheritance—and who consequently stands outside the norm of history as a whole. One of John Keegan’s “insignificant exceptions.” There is, after all, only one Joan of Arc. The number of women who enlisted disguised as men in any given war is statistically insignificant. The circumstances that led women to fight at the siege of Sparta or Tenochtitlan or Leningrad were desperate. And so on.

Looking at women warriors in isolation, it is also easy to accept the way in which the accomplishments (or even existence) of a specific woman warrior are dismissed. That Telesilla or Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer or Artemisia II didn’t do what the sources claim she did. That an unknown man stood behind Matilda of Tuscany pulling the military strings. That Fu Hao played no more than a symbolic role on the battlefield. That Mawiyya or Kit Cavanagh didn’t exist. That any ancient remains buried with a sword are male. That the women who stood on the ramparts and fought back don’t count as warriors because if they were soldiers (and therefore men) the fact that they stepped forward to fire a cannon or picked up a rifle wouldn’t be worth remarking on. Looking at women warriors in isolation, it doesn’t matter that Katherine of Aragon successfully defended England against invasion because everyone knows the important part of her story is Henry Tudor’s inability to father a son. You can overlook the fact that Alexander the Great or Edward the Elder of England had a sister who led troops into battle. When you step back and look at women warriors across the boundaries of geography and historical period, larger patterns appear—parallels not only between the stories of the women themselves but in the ways their stories are told and not told. Some times, places, and social structures are more accepting of women warriors than others. (As a general rule, horse-based cultures, honor cultures, and tribal societies do a better job with the concept than large empires or regular armies—with the extraordinary exception of China.) The accomplishments of women are questioned, undercut, and ignored by scholars in consistent ways across periods. There are unexpected linkages between women, particularly between mothers and daughters—looked at in the context of Cynane, Matilda of Tuscany, Katherine of Aragon, and Amina of Zazzau, the legend that the Trung sisters learned the arts of war from their mother seems a lot more possible.

But the main thing that struck me when I looked at women warriors across cultures rather than in isolation is how many examples there are and how lightly they sit on our collective awareness. I began with hundreds of examples. I ended with thousands.(…)

Exceptions within the context of their time and place? Yes. Exceptions over the scope of human history? Not so much. Insignificant? Hell, no!”

Women warriors: an unexpected history, Pamela D. Toler

(Equestrian portrait of Madame de Saint-Baslemont, by Claude Deruet, 1646)

Alberte-Barbe d'Ernécourt, Dame de Saint-Baslemont - The amazon of Lorraine

Alberte-Barbe (1607-1660) was the eldest daughter of a distinguished family from Lorraine. This region between France and Germany is now part of France, but was at that time an independent duchy. Intelligent, robust and athletic, Alberte-Barbe was also generous and concerned with the well-being of the people who lived on her family estates.

In 1624, she married Jean-Jacques de Haraucourt, lord of Saint-Baslemont. The pair rode on horseback and hunted together. Of their children, only a daughter survived to adulthood. The couple would soon be parted as the Thirty Years’ War raged in Europe. Jean-Jacques left to join the Duke of Lorraine who was fighting against the French. It appears that Alberte-Barbe had sympathies for the French crown, as she sometimes gave safe passage to French troops. She nonetheless respected and supported her husband’s choice and paid his ransom twice when he was made prisoner.

Alberte-Barbe busied herself with defending her territories at the head of a small, but well trained militia. She led from the front, sword in hand and was often found fighting hand-to-hand with her enemies. She fought against French and enemy soldiers as well as marauding brigands, preventing them from pillaging her lands. Her first victory took place in 1636 when she defeated a band of 100 French cavalrymen trying to drive off her cattle herd.

She fought for eight years and her biographer states that she was never wounded or defeated. She also reportedly challenged a military officer who caused troubles on her lands to a duel and defeated him. The man thought he was fighting against “the knight of Saint-Baslemont” and was ashamed and astonished when Alberte-Barbe revealed her real identity before leaving. Her military reputation was so impressive that many refugees came to her lands.

Alberte-Barbe was nonetheless merciful and spared those who surrendered, she also offered medical care to the wounded, friends or foes alike. This benevolence could be observed in other aspects of her life, for instance, she established a weekly “soup kitchen” that fed 200 hundred people, often served by Alberte-Barbe in person. She gave dowries to young women and clothing to young men entering the monastery and cared for the sick.

She was also a very religious woman and attended the mass daily. Alberte-Barbe was also a playwright and wrote a religious tragedy title The twin martyrs and published in 1650. After her husband’s death in 1644, she refused to remarry. She died in 1660.

Bibliography:

D’Orléans Nemours Marie, Mémoires de la duchesse de Nemours

Hacker Barton, Vining Margaret (ed.), A Companion to Women’s Military History

Lynn John A., “Saint-Baslemont, Alberte-Barbe D’Ernecourt, Madame de”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.2

“Portrait équestre de Madame de Saint-Baslemont”

Tribout de Morembert Henri, Hommes illustres de Lorraine

Winn Colette H., Larsen Anne R., Writings by Pre-Revolutionary French Women

Post link

Milunka Savić - World War I’s most decorated woman

Milunka Savić (c.1890-1973) was born in Serbia. She took her brother’s place and enlisted in the army under the name Milun Savić during the Second Balkan War. During the Battle of Bregalnica, Milunka was leading her tenth charge at the head of a squad of men when she was wounded when an enemy grenade blew up at her feet.

Her real identity was discovered and Milunka was brought to her commanding officer who offered her to join the nursing corps. Milunka refused. She told him that she wouldn’t accept a position that didn’t allow her to bear arms to defend her country. Her superior thus promoted her to junior sergeant and allowed her to stay in the infantry.

Milunka was thus openly fighting as a woman when the First World War began. She was part of a prestigious unit nicknamed “The Iron Regiment”. During the Battle of the Kolubara river (3-9 December 1914), she single-handedly assaulted an Austrian trench, hurling grenades, and subsequently captured 20 Austrian soldiers. Milunka excelled at throwing grenades at used them to destroy the enemy machine guns. Her performance was so impressive that she was later nicknamed “The Bomber of Kolubara”. Milunka later told the press that during her childhood in the countryside, she spent a lot of time herding sheep. She and her young comrades played at hitting different targets by throwing stones. This was how she acquired her skills.

She went on to participate in several battles and fought alongside the French soldiers on the Macedonian front. In 1916, she single-handedly captured 23 Bulgarian soldiers. She was hospitalized at least 3 times and earned many awards for her performance in combat. Among the decorations Milunka received were the French Légion d’honneur, the Croix de guerre, the Cross of St. George, the Most Distinguished order of Saint Michael and Saint George and the Serbian Medal for Bravery.

(Milunka in uniform in 1917)

Milunka’s case wasn’t unique. A young woman from Belgrade named Sofija Jovanović served like her in the Second Balkan War and the First World War. Remarkably cultivated, Sofija attracted the attention of the foreign press and earned the nickname of “Serbian Joan of Arc”. She too received a number of Serbian medals for her merits.

(Sofija Jovanović)

Two school teachers named JelenaŠaulić and Ljubica Cakarevic also fought among the Serbian troops. A Slovenian woman, Antonija Javornik, was also part of the Serbian army, as was the British womanFlora Sandes .

(Jelena Šaulić)

(Antonija Javornik)

Milunka married after the war and gave birth to a daughter, but the union didn’t last long. She afterward adopted three other girls. Since she had never been to school, Milunka had to work as a cleaning lady, but faced the situation with courage and dignity. She managed to send all her daughters to school and helped thirty children, many of them from her natal village, to get a proper education as well.

During the Second World War, Milunka still found a way to help her country. She notably hid antifascists in her home and nursed them, creating a kind of secret hospital. She died in Belgrade in 1973 and was buried with military honors. A street in Belgrade is named after her.

(Milunka in 1966)

References:

Breverton Terry, Breverton’s First World War Curiosities

Larson Carmichael Jacqueline, Heard Amid the Guns, True Stories from the Western Front, 1914-1918

Toler Pamela D., Women warriors: an unexpected history

Post link

María la Bailadora - Soldier at Lepanto

The naval Battle of Lepanto took place on October 7,1571. The Catholic states of the Holy League fought against Ottoman Empire and secured a decisive victory.

Fighting bravely among the Spanish soldiers was a woman: María la Bailadora (”the dancer”). María had wanted to follow her lover and had thus joined the soldiers dressed as man. A report of the battle tells that she was particularly skilled with an arquebus. Encountering an enemy at close quarters, she stabbed and killed him.

As a reward for her bravery, her name was inscribed in the official register of the soldiers, thus allowing her to earn a pay.

María’s story reminds of another Spanish woman, AnaMaría de Soto (fl.1793-1798) who enlisted in the marine infantry in 1793. She fought in naval battles, served for several years, was promoted to sergeant, but was discharged when her sex was revealed after a medical examination.

Bibliography:

Claramunt Soto Alex (ed.), Lepanto. La mar roja de sangre

Fields Nic, Lepanto 1571: Christian and Muslim Fleets Battle for Control of the Mediterranean

Parente Rodriguez Gonzalo, «Una mujer en la Infantería de marina del XVIII»

Post link

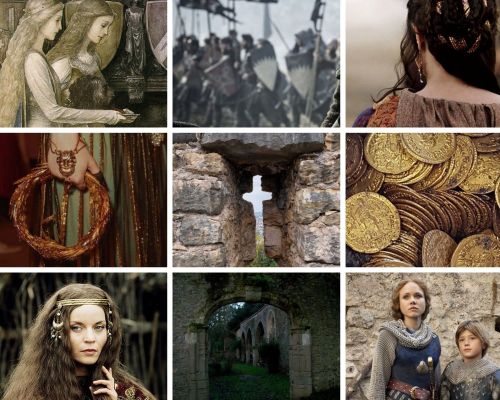

Richilde of Hainaut - Fighting countess

Richilde (c.1018-1074) was countess of Hainaut (a territory straddling the border between present-day French and Belgium) during her first marriage between 1040 and 1051. She later married count Baldwin VIofFlanders and thus became countess of Flanders. She entrusted the children born of her first marriage to the clergy: her daughter became a nun and her son, who was probably physically disabled, became a bishop.

Richilde gave birth to two sons from her second marriage and was determined to protect their inheritance. When Baldwin VI died in 1070, his brother Robert the Frisian, wanting the county for himself, marched on Flanders with his army.

The resourceful Richilde recruited men from Hainault and asked for king Philipp I of France’s help, convincing him to bring her an army of men from northeastern France.

Richilde was present and captured during the ensuing battle of Cassel in 1071. Though her exact role is unclear, the chroniclers saw her as the leader of the troops and reported her participation matter-of-factly, without finding it appalling. However, it was during the 13th century that a chronicler felt the need to explain her presence on the field by accusing her of sorcery and having tried to throw “magic powder” at the opposing army.

Richilde was unable to secure Flanders and withdrew to Hainaut where she ruled as a regent. She acted as a protector of the church and built a monastery. Her son took power in 1083 and Richilde retired to a nunnery where she died the following year.

Other countesses of Flanders led troops to defend their lands. Clemence of Burgundy, wife of Robert II (1065-1111) did the same. Having ruled the county and struck coins in her own name while her husband was away on crusade, she wielded considerable power. Her dower included several towns. She remained active after her husband’s death, but her son Baldwin VII named his cousin Charles of Danemark as his heir. After Baldwin’s death, Charles tried to seize a part of Clemence’s dower. She raised an army against him, but was forced to negotiate after Charles captured four of her towns. This marked the end of her rule and she withdrew to her remaining holdings in Southern Flanders for the rest of her life.

Another notable case was Sybil of Anjou (d.1165), wife of count Thierry (fl.1128-1168). Sybil ruled the lands while her husband was crusading. A pious woman, she was instrumental in strengthening the relationship between the count and the church. While Thierry was away, count Baldwin IV of Hainaut invaded Flanders and started pillaging. Even though she was pregnant, Sybil raised an army and attacked Baldwin with a “virile heart”, burned villages and towns and pillaged the countryside. Baldwin fled and “acquired no honor in this campaign”. Sybil managed to secure a truce. Her son Philip later remembered the time “when my mother Sybil, countess of Flanders, strongly governed the principality of Flanders”. The documents indeed show Sybil as a vigorous and decisive leader.

Bibliography:

Cassagnes-Brouquet Sophie, Chevaleresses, une chevalerie au féminin

McLaughlin Megan, The woman warrior: Gender, warfare and society in medieval Europe

Nicholas Karen S., “Countesses as rulers in Flanders”

Post link

“At the battle on the Danube in 971, beforeSviatoslav sued for peace, there came a black day of defeat for the Rus, when the Byzantine emperor’s cavalry drove the Rus warriors back against the walls of the town and many were “trodden underfoot by others in the narrow defile and slain by the Romans when they were trapped there.” As the victors were “robbing the corpses of their spoils,” wrote John Skylitzes in his Synopsis of Byzantine History a hundred years later, “they found women lying among the fallen, equipped like men; women who had fought against the Romans together with the men.”

The real valkyrie, The hidden history of viking warrior women, Nancy Marie Brown

Émilienne Moreau - The heroine of Loos

Émilienne Moreau (1898-1971) was born to a family of coal miners. Her father moved to Loos-en-Gohelle where she helped him run his shop. She was 17 in when the First World War broke out and was studying to obtain the qualification for becoming a schoolteacher. The German soldiers, however, advanced toward her city. Émilienne warned the French troops of the position of the German artillery, but the French had to retreat.

The civilians began to live in difficult conditions. Émilienne’s father died due to the “privations and anguish” of the occupation. She set herself as a teacher for the local children due to the school having closed. In September 1915, the British troops approached tried to retake the town. Émilienne thus warned them of the positioning of the German defenses.

During the battle, she nursed the wounded in her house. Émilienne also took arms to defend herself. She notably threw grenades to help a fellow Scottish soldier. As she recounted in her memoirs: “I had killed men. Everything happened within minutes. I didn’t even have time to think(…)”. She grabbed a gun and killed two German soldiers who fired at her through the door.

The town was liberated and she and her family evacuated. Émilienne was awarded the Croix de Guerre from the French and received two additional medals from the British. The newspaper Le Petit Parisien also commissioned her to write her memoirs.

Émilienne didn’t give up on her dreams and became a schoolteacher. In 1932, she married Just Evrard, who was like her involved in the socialist party SFIO. In 1934, Émilienne became the Secretary General of the socialist women in the Pas-de-Calais.

As Germany invaded France again in 1940, Émilienne took the path of resistance. She pursued her militant activity and accomplished many missions in Paris, ToulouseorMarseille. She barely avoided arrestation twice in 1944 and managed to escape to London.

Back to France in September 1944, she became one of the six women to be made Compagnon de la Libération (”Companion of the Liberation”) and received the Croix de la Libération (”Cross of the Liberation”). She remained politically active and played a leading role within her party. She died in Lens, in 1971.

If you want to support me, here’s the link to my Ko-Fi

Bibliography:

Fell Allison F., Women as Veterans in Britain and France After the First World War

Malassis Frantz “Emilienne Moreau-Evrard”

Post link

“Estonian folklore revolves around women, and while its pagan culture was warlike, women were not excluded from that facet of life. In ancient Estonian burials, bodies were buried in communal tombs, marked by cairns, or coverings of stone. The bodies were allowed to rot before burial; then parts of skeletons of all ages and sexes were so intermingled that archaeologists cannot distinguish individuals, much less determine their gender.

(…)

Estonia’s communal burials held few or no grave goods, but in the middle of the tenth century—Hervor’s time—individual burials like those found throughout the Rus world became popular. Yet even in these individual graves, filled with weapons and jewelry and a skeleton capable of being sexed, gender remains irrelevant. Estonian women and men wore identical jewelry—unlike in neighboring lands, where men, though gaudily bedecked, had their own jewelry styles. Likewise, weapons are found in up to 30 percent of female graves in tenth-century Estonia, along with nongendered objects like tools, implying that women had equal access to power.”

The real valkyrie, The hidden history of viking warrior women, Nancy Marie Brown

“Coming upon Hervor’s Song for the first time, as a college student new to Old Norse literature, I wondered not should Hervor wield her father’s Flaming Sword, cursed as it was to destroy her family line, but why would she want to? Wouldn’t a woman rather fight with a bow, standing out of the fray and picking off her targets?

Now I realize my young imagination was cramped by those Victorian stereotypes that say women lack the ruthlessness to fight. That they are, by nature, too dainty to wield a heavy Viking sword. It took one evening with a group of Viking reenactors to disabuse me of that nonsense: Their best fighter happened to be female.

Could Hervor (the name the author gave to the Birka woman) have fought well with a sword? Indeed, she could have. She was taller than most people of her day and well nourished. Because of the way Viking armies were organized in the tenth century, she had ample opportunity to spar with other warriors. Many Viking women may have trained in sword fighting in their youth. When Gudrun in one Viking poem “took up a sword and defended her brothers,” she reveals her valkyrie training: “The fight was not gentle where she set her hand,” the poem says. She felled two warriors. She struck one “such a blow, she cut his leg clean off. She struck another so he never got up again; she sent him to Hel, and her hands never shook.” Though a wife and a mother, Gudrun remained a warrior woman, the poet asserts, with the skill and reflexes needed to target a weak spot (the legs) and to strike hard.”

The real valkyrie, The hidden history of viking warrior women, Nancy Marie Brown

Lydia Litvyak - The white rose of Stalingrad

Lydia Vladimirovna Litvyak (1921-1943) was fittingly born on August 18, the Soviet Air Fleet Day or Aviation Day. She made her first solo flight at 15 and was training as a flight instructor by the age of 17.

In 1937, her father was accused of having committed crimes against the Communist Party and arrested. She never saw him again. Unlike her brother, Lydia refused to change her name.

When World War II began, Lidya had already trained 45 pilots at the Kirov Flying Club in Moscow. The USSR’s Airplanemagazine praised her for having carried out a record number of training flights in a single day (over 8 hours in flight). Lydia wanted to join the war effort, but her appeal was rejected.

However, things changed when Marina Raskova was allowed to create female aviation regiments. Lydia joined her recruits. She was friendly and curious toward the others. She first refused to have her hair cut, but had to give up due to Marina’s insistence. Lydia was full of enthusiasm, she wrote her mother that she was “thirsting for battle”.

In September 1942, she and some of her female comrades were moved to an entirely male regiment. They stood their ground and quickly adapted. It was during this month that Lydia was deployed in battle for the first time. She shot down two enemy planes during the fight and thus became the first woman in the world to shoot down an enemy combat aircraft on her own.

Story has it that a renowned German ace she had shot down was captured, and asked to meet the person who defeated him. When he saw Lydia, he couldn’t believe it was first. Lydia, however, used hand movements to reconstruct their duel and he was forced to admit the truth. Impressed, he offered her his wristwatch, but she refused.

Nicknamed the “White rose of Stalingrad”, Lydia flew with a bouquet of flowers stuck on her dashboard. A white lily was painted on her plane. To become an ace, a pilot had to shoot down five aircrafts. Lydia shot down 11 enemy planes by herself within a year and added a “shared kill” to her performance. She was granted the status of “free hunter”, meaning that she could go searching for enemy aircraft or ground forces on her own initiative.

On March 22, 1943, she found herself outnumbered by the enemy two to one. She shot down a German plane, but was wounded in the leg. Lydia then found herself surrounded by six enemy planes. She flew straight in the middle of the German aircrafts and shot one of them. She managed to escape and to land, before fainting. This exploit turned her into a celebrity.

In July, she and six or five of her comrades found themselves fighting thirty six enemy planes. She shot a German bomber and a fighter, but was wounded in the shoulder and the leg and had to crash-land her plane. She refused to be hospitalized. The death of her best friend in battle didn’t stop her. A week later, she returned to combat.

She was flying her fourth mission on August 1, 1943, when she was ambushed by a superior number of enemies. One of her comrades saw her dive into the clouds to escape. This was the last time she was seen. Nobody could find her body or plane. Since she was declared “missing”, she couldn’t be granted to rank of “Hero of the Soviet Union”.

After the war, search for her body and plane were conducted and it was discovered that she had possibly been found and buried in the village of Dmitrievka in Ukraine. On May 5,1990 Mikhail Gorbachev finally made her a hero of the Soviet Union.

Lydia’s last letter to her mother said:

“I am completely absorbed in combat life. I can’t seem to think of anything but the fighting. I long … for a happy and peaceful life, after I’ve returned to you and told you about everything I had lived through and felt during the time when we were apart. Well, good-bye for now. Your Lily.”

If you want to support me, here’s the link to my Ko-Fi.

Bibliography:

Sakaida Henry, Heroines of the Soviet Union 1941-1945

Wayne Elizabeth, A Thousand Sisters: The Heroic Airwomen of the Soviet Union in World War II

Post link

How the women of Palencia fought the English and saved their city

In 1388, the Spanish town of Palencia was under attack by John of Gaunt, earl of Lancaster, who had landed in Spain to defend his claim to the kingdom of Castile. All the men had left the city to fight in king John I’s army. The women stayed behind.

When they saw the English army approaching, the townswomen decided to resist. They dressed themselves in male clothes, took the weapons they could find and stationed themselves on the walls.

The English thought it was going to be an easy victory and began the attack. The women, however, fought and repelled the waves of assault. The armies of the king of Castile came to the rescue and John of Gaunt had to lift the siege.

The women’s exploits were rewarded by the king and they no longer to bow in front of him, a privilege generally only granted to knights. This was signaled by the band of fabric they now wore on their clothes.

A commemorative plaque reminds today of their exploits and a mention to this episode is made in the city’s hymn. The band they wore became part of Palencia’s traditional costume.

This isn’t the only time in Spanish history where women defended their city in the absence of men. In Orihuela, in the beginning of the 8th century, the women fooled the attackers army by occupying the walls armed and dressed male clothes. Thinking that the city was well guarded, the enemy didn’t try to besiege it. In the 12th century, Jimena Blazquez and the other women used successfully the same ruse in Ávila. They were later rewarded with the right of participating to the town’s council. In the 13th century, it was the lords’s wife who convinced all the women of Jaén to take arms and to stand on the walls, thus preventing the city’s capture.

If you want to support me, here’s the link to my Ko-Fi.

References:

Las Mujeres y las guerras, el papel de las mujeres en las guerras de la Edad Antigua a la contemporánea

“Mujeres Palentinas, Caballeros De Honor”, Casa de Palencia

Santamarta del Pozo Javier, Siempre estuvieron ellas

Post link

Pretty Nose - Arapaho war chief

Pretty Nose (b.1851-d.c.1952) was a war chief of the Arapaho people. Her red, black and white beaded cuffs signaled her rank. She distinguished herself by fighting at the Battle of The Little Bighorn in 1876 where the Arapaho, Lakota and Northern Cheyenne defeated the U.S. army.

The above photography was taken at Fort Keogh in 1878. Pretty Nose lived for the rest of her life at a reservation. She was still alive in 1952 and saw her grandson, Mark Soldier Wolf, come back from the Korean War in 1952. By a clear spring morning, Soldier Wolf was reunited with his 101-year-old grandmother. Pretty Nose wore a buckskin dress with elk teeth and her cuffs.

When she saw him, Pretty Nose began to sing a war song. As her grandson later recalled: “It was really something when she sang that song. It didn’t sadden me, just put more strength into me and I wished I could have just stayed there with that song.”(Click here if you want to listen to thesong sung by her grandson).

Warrior women of the Little Bighorn:

References:

Ahtone Tristan, “The story of Soldier Wolf”

Hall Alan R., A Man Called Plenty Horses, The Last Warrior of the Great Plains War

Post link

Minnie Hollow Wood and One Who Walks With the Stars - Lakota warriors

Minnie Hollow Wood (c.1856-1930′s) was a Lakota woman and wife to chief Hollow Wood. In 1876, she fought at the battle of Little Bighorn, which ended in a victory of the native tribes against the U.S. army. Minnie distinguished herself when fighting against the U.S. cavalry and was awarded the right to wear a war bonnet.

The tide later turned, and she and her husband surrendered to general Nelson Miles. In 1877, she was among the prisoners at Fort Keogh. She and her husband were later transferred to a reservation where they lived the rest of their lives. The above photograph was taken in 1930 when Minnie Hollow Wood was 74.

Oglala Lakotawoman One Who Walks With the Stars also resisted Custer’s soldiers. She was the wife of Brulé Lakota (or possibly an Oglala) chief Crow Dog. Her story was preserved by survivors of the fight. While her husband didn’t kill anyone during the battle, she killed two soldiers who tried to swim across the river.

Warrior women of Little Big Horn:

Bibliography:

Hirschfeld Arlene, Paulette F. Molin, The Extraordinary Book of Native American Lists

Lawson Michael L., Little Bighorn Winning the Battle, Losing the War

Liberty Margot,”Cheyenne Primacy: The Tribes’ Perspective As Opposed To That Of The United States Army; A Possible Alternative To “The Great Sioux War Of 1876″

Miller Humphrey David, Custer’s fall

Wakim Dennis Yvonne, Native American Almanac More Than 50,000 Years of the Cultures and Histories of Indigenous Peoples

Post link

Nanye’hi “Nancy” Ward - Beloved woman of the Cherokee

Nanye’hi (1738-1822) was a woman the Cherokee nation. In the early 1750s she married a man named Kingfisher. In 1755, she went with him on a military expedition against the neighboring Creeks. Women went with war parties to draw water, gather firewood and cook since male warriors weren’t supposed to perform these tasks due to the separation of gender roles.

During a battle, Nanye’hi hid behind a log, but her husband was shot and killed. She took his gun and fought on, leading the Cherokee to victory. Though war was technically a male domain, there were still instances of Cherokee women taking arms. During the American Revolution, a Cherokee woman “painted and stripped like a warrior and armed with bows and arrows” was found dead on the battlefield. During the same period, another woman slew her husband’s killer on the battlefield and was allowed to join the warriors in the war dance carrying her gun and tomahawk.

In the early 19th century, missionary John Gambold met an old woman named Chicouhla who had “gone to war against hostile Indians and suffered several wounds”. A woman namedCuhtahlatahrallied the warriors after her husband was killed in defending the village. She took his tomahawk, shouted “Kill, kill!” and lead her people to victory. In the 1880s a Cherokee woman whose name meant” “Sharp Warrior” was active.

Nanye’hi was rewarded for her heroism and granted the title of Agigaue,which translates as “Beloved Woman” or “War Woman”. There was, for instance, a “War Woman’s creek”, commemorating the stratagem of a woman who had led her people to victory and was after rewarded with a chiefly position.

Women like Nanye’hi were indeed influential and powerful. Their words were listened to and they were the head of the Women’s Council, involving representatives from each clan. Nanye’hi could also seat at the council of Chiefs. Agigaue also participated in martial dances and prepared the “Black Drink” that was given to the warriors who were about to go on the warpath. She had a right to spare prisoners who had been sentenced to death and in 1776 saved a white woman named Mrs. Bean. In 1781, she and other women helped five traders to escape to safety.

In the late 1750′s, Nanye’hi married white traded Bryant Ward and anglicized her name as Nancy. They had a daughter together named Elizabeth. Before 1760, he returned to live with his other family and Elizabeth remained with her mother. Nanye’hi didn’t, however, completely sever ties with him and sometimes visited him.

During the American Revolution, Nanye’hi sided with the new United States, a rare position among the Cherokee. In 1776, she warned settlers of an impending Cherokee attack. It seems that her decisions came from pragmatism, as she was aware of the superiority of the settler’s superiority in numbers and weapons. In October 1776 Colonel William Christian led a devastating raid on Cherokee territory, but spared Nanye’hi’s town of Chote out of respect for her. Chote was nonetheless destroyed in 1781, Nanye’hi was taken into custody, but was later allowed to leave to rebuild the town.

In 1781, Nanye’hi appeared at her a treaty conference with United States commissioners held on the Long Island. There had been cases before her of Cherokee women serving as ambassadors. She said:

“You know that women are always looked upon as nothing; but we are our mothers and you are our sons. Our cry is all for peace; let it continue. This peace must last forever. Let your women’s sons be ours; our sons be yours. Let your women hear our words.”

Her plight was heard. The original demands were revised and the Cherokee only had to give their land north of the Nolichucky River instead of giving all their lands north of the Little Tennessee River. She called for peace again in 1785, but this time the Cherokee had to cede more lands.

In the 19th century, the Cherokee government system was changing and there was less and less place for a woman like the aging Nanye’hi. United States agents who tried to “civilize” the Cherokee by imposing their values and the statues of women in the nation began to decline. In 1819, her town was ceded and she had to leave with her retinue for the Ocoee River near the present town of Benton, where she ran a sort of inn for travelers. She died in 1822. She thus didn’t live to see her people’s exile on the Trail of Tears following the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

Bibliography:

Harris McClary Ben, “Nancy Ward: The Last Beloved Woman of the Cherokees”

Perdue Theda, “Nancy Ward”, in: Glinton Catherine G. (ed.), Portraits of American Women from Settlement to the Present

Post link

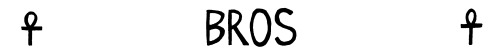

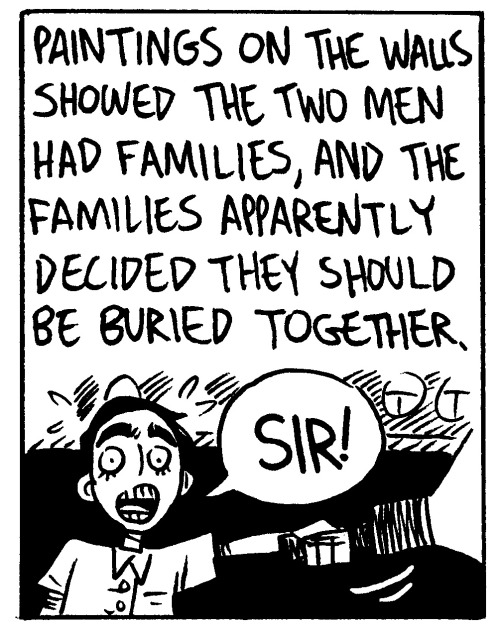

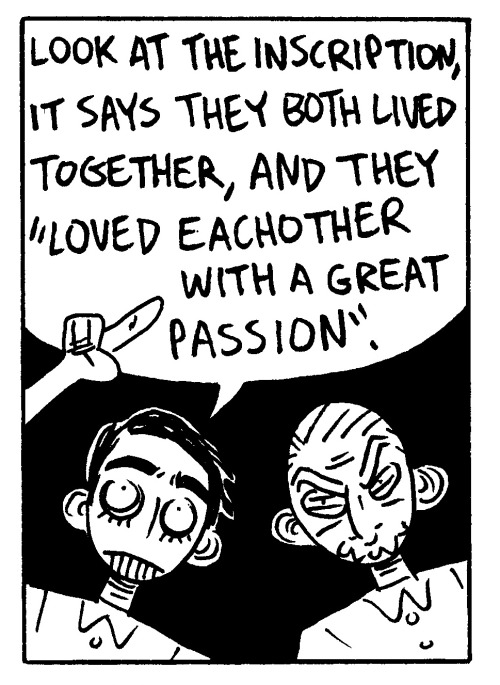

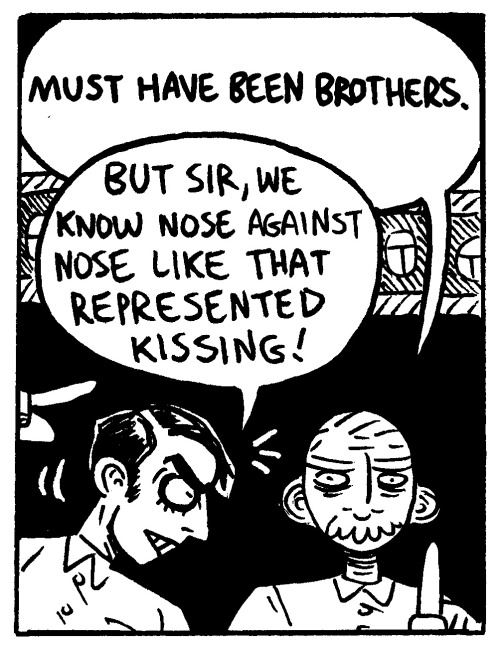

Informative Ancient Egypt Comics: BROS

Our1st place contest winner requested a Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep comic as their prize.

I took a class about Ancient Egypt last semester and we had a whole lecture dedicated to talking about how gay Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were.

Their tomb walls were decorated with scenes of them ignoring their wives in favor of embracing each other. In one scene, the couple is seated at a banquet table that is usually reserved for a husband and wife. There’s an entire motif of Khnumhotep holding lotus flowers which in ancient Egyptian tradition symbolizes femininity. Khnumhotep offers the lotus flower to Niankhkhnum, something that only wives were ever depicted as doing for their husbands. In fact, Khnumhotep is repeatedly depicted as uniquely feminine, being shown smaller and shorter than his partner Niankhkhnum and being placed in the role of a woman. Size is a big deal in Egyptian art, husbands are almost always shown as being larger and taller than their wives. So for two men of equal status to be shown in once again, a marital fashion, is pretty telling. Not to mention they were literally buried together which is the strongest bond two people could share in ancient Egypt, as it would mean sharing the journey to the afterlife together.

And yet 90% of the academic text about these two talks about these clues in vague terms and analyze the great “brotherhood” they shared, and the enigma of Khnumhotep being depicted as feminine. Apparently it’s too hard for archaeologists to accept homosexuality in the ancient world, as well as the possibility of trans individuals.On the last note, I was walking around the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and there is a mummy on exhibit. It caught my attention because the panel that was describing it was talking about how it was a woman’s body in a male coffin and wow, the Egyptian working that day really screwed that up. My summary, not actual words, sorry I can’t remember verbatim but it basically said that someone screwed up.

They claimed that the Egyptians screwed up a burial.

The Egyptians. Screwed up. A burial.

Now I’m not an expert in Ancient Egypt but from what I know, and what the exhibit was telling me, burials and the afterlife and all that jazz DEFINED the Egyptian religion and culture. They don’t just ‘screw up’. So instead of thinking outside the box for two seconds and wonder why else a genetically female body was in a male coffin, the ‘researchers’ blatantly disregard the rest of their research and decided to call it a screw up. Instead of, you know, admitting that maybe this mummy presented as male during his life and was therefore honorably buried as he was identified. But it would be too much of a stretch to admit that a transgender person could have existed back then.

(Sorry I can’t find any sources online and it’s been like 2 years but it stuck in my mind)

There’s a lot of bigoted historian dragging on my dash these days and it makes me happy.

Once again, more proof that we queers have ALWAYS been here, and it’s a CHOSEN narrative to erase them.

Reblog because ancient gay power

ALWAYS. REBLOG. THIS.

And also ancient gay power.

Ancient Gay Power

Can we talk about the Vikings for a second? Because this same fuckery applies there.

First, you’ve of course got the biological women who were buried as warriors.

One such woman was buried with two horses, heaps of weapons and, most notably, a sort of gameboard in her lap that was used to plan battle strategy. All of this indicates a Viking who commanded troops and led them into battle. Naturally, therefore, it was impossibleit was a woman. Researchers were forced to test the bones four different times, each time concluding that, yes, this is a woman. There are still people who argue that there are two bodies in the graves or that, basically, they scienced wrong.

The body of another biological woman was discovered in a grave surrounded by weapons but it was automatically dismissed she was a warrior because, you know, woman. Then they looked at her skull more closesly and saw that she took a sword hack to the face and. it. might. not. have. been. what. killed. her. See a reconstruction of her face using facial recognition software.

Now let’s talk about the myth that Viking men had long hair. Every image and description we can find of Viking men from their time period shows them with short, practical haircuts. That’s not to say that no Viking man ever had long hair, but in general, hair seems to have been worn short in a number of styles - after all, sea wind is not kind to long hair, nor is horseback riding or battle; you can get blinded, tangled up or grabbed by your enemy.

So where did this myth come from? The same place as all the rest of this: bigoted historians. In the 19th century, scholars were really beginning to delve into the old Norse sagas and translate them and speculate on their meaning.

If you’re at all familiar with the Hebrew Old Testament, you’ll know the God contained therein is mostly large, angry and masculine but with moments of softness, empathy and compassion. He is even called El Shaddai which translates roughly to something like ‘one who feeds with breasts’. This is further expounded on in the Christian New Testament with God compared to a mother, a refuge, etc. He’s not the only high god given male and female attributes.

Odin is portrayed similarly (large, angry and masculine) but like the Hebrew/Christian God can be deeply caring. At times he was specifically depicted with the long hair of a woman to make this very obvious. Scholars could not believe that almighty ODIN could have a female side, so they decided that Viking men must have had long hair.

The second component was the existence of a cult called what translated to Long-Hair(Like A Woman’s). In mythology there were two brothers who went on various adventures together, including slaying a dragon. Whether they were based on any actual people or not is unknown. What is known is that after their deaths they more or less became the Norse equivalent of saints and a cult formed around them. For reasons that are unclear, these cult priests, who were biologically male, dressed in womens’ clothes and wore their hair long like women, earning them their name. They were fearsome warriors, often taking up arms to defend their shrine or to join in a particular cause and battle, fighting in their womens’ garments.

Again, historians could not accept the idea of transwomen Vikings or even Vikings who embraced their sacred feminine sides, which ever the case may be, and instead, long hair was just a Viking way.

This erronous myth of long-haired vikings is everywhere and the next time you see it, remember it’s the product of bigots and historians who can’t be bothered to do their job properly.

Post link