#neoproterozoic

Dickinsonia – Late Ediacaran (558-555 Ma)

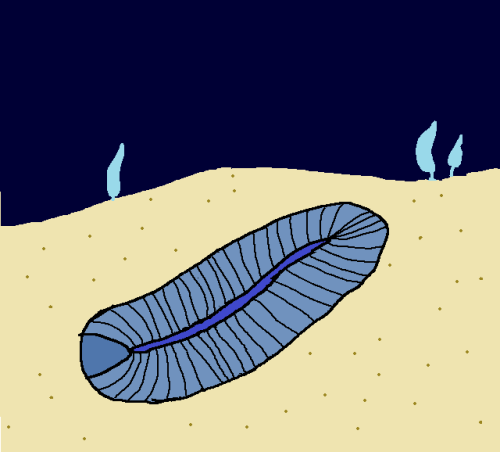

I may have been a little too quick to declare the end of my hiatus… But don’t worry, because I’ve got a lot to say about our featured organism today. We’re going back to the Ediacaran to talk about one of my favorite fossils of all time, called Dickinsonia. Its shape is a bit simplistic, so I gave it a little background, with some Charnia guest stars.

Like I mentioned last time, the Ediacaran biota are a loose group of super-ancient organisms who existed before the Cambrian Period, at the very end of the Proterozoic Eon. These are widely considered to be the first multicellular organisms, and lived during the second half of the Ediacaran period, in a span of about 40 million years. Many of these fossils come from the Flinders mountain range in Australia, where their squishy forms were preserved in exquisite detail, though they’re known from other locales too, like Newfoundland, the Ukraine, and England. These fossils are abundant just about wherever Ediacaran rocks can be found, which is really strange considering this was before the evolution of any hardened organic structures. Consider also that younger fossil beds like the Burgess Shale exist because something lucky happened to preserve everything. The Ediacaran biota are just kind of there. Why are there so many squishy organisms fossilized, and why in such detail? The most likely answer has to do with one of the hallmarks of this alien past.

The seafloor of the Ediacaran period was caked in squishy, lumpy carpets of bacteria or archaea feasting on the chemicals around them. These communities of microorganisms are called microbial mats, and although they were almost universal back then, they’re rare today. This is probably because animals who are really good at eating them evolved. If a microbial mat were to form in the middle of a busy reef, it wouldn’t be long at all before some fish or arthropod or something said, “Oh dunk, free food!” and ate it. That being said, they still thrive in remote waters that lack those predators.

So, the best explanation for the preservation of the Ediacaran biota are these microbial mats. They didn’t eat organic matter, so if something big died and sunk into the mat, the microbes covering it would unwittingly protect its impression from being covered by sand. Add a nice layer of sediment and several thousand years, and boom. Those softboys are preserved until subduction destroys the rocks forever.

So, anyway. What’s a Dickinsonia? Some sort of sea pancake? One of the trademarks of the Ediacaran biota is that we really have no clue what we’re looking at. Currently, their fossils are sorted into groups called morphotypes. A morphotype isn’t a real taxonomic division, but a method where organisms are grouped together based on their shape. So, you’ve got circles, and you’ve got fronds, basically. That doesn’t really mean anything though, because I could put snakes, caecilians, eels, and earthworms into the same morphotype—which I call Noodlemorpha—even though they’re all only distantly-related to each other. We just know that little about the lifeforms of the Ediacaran. Put all of that aside for a minute though, because Dickinsonia is special in that we actually know what it is, as of last year. After decades of postulating and debating, a conclusion has been reached. Dickinsoniais…

a bilateral animal.

Yeah, sorry, that’s it. We can’t really say anything else for sure. Still, that’s huge in the context of these organisms, most of which are so weird a new kingdom has been seriously proposed, called Vendozoa. To be able to identify one of them as anything definite is a huge landmark for the scientists who study these fossils.

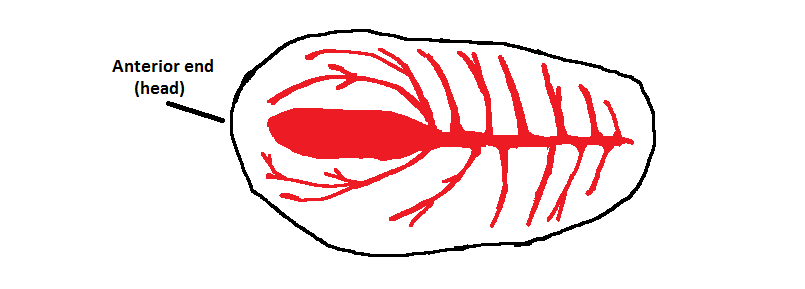

Dickinsonia lived on the seafloor. It crept along ever-so-slowly, and sifting food out of the sand and leaving trails of circular holes in the microbial mats beneath it. The segments on its body are called isomers, and might have been filled with organic fluids. t would have been very soft and flexible, like a segmented water balloon, but a bit thicker. It didn’t really have to be all that durable considering there wasn’t anything around to attack it. Some fossils even show impressions of possible muscle fibers, and a vein-like structure inside of its body, which some scientists have interpreted as a basal digestive system. It looked something like this, with the internal structure in red:

I really, really wanted to link to one of these fossils, but I wasn’t able to find any good pictures of the actual specimens. I can’t stress enough how absolutely extraordinary it is that a fossil this old might still show the internal organs of the thing that left it behind. We can guess a lot about the internal organs of things like dinosaurs based on similar animals alive today, but we’d have absolutely no idea what Dickinsonia looked like under the hood without these surprisingly detailed fossils.

Newly-bornDickinsonia looked like little circular pills without any isomers. We aren’t even close to ready to asking how this thing reproduced, by the way. Maybe it was like a sponge and just kind of spat its business into the sea and hoped for the best, but we have absolutely no idea. As the animal aged, new isomers grew from its posterior end, elongating its body. It grew throughout its entire life, getting bigger and bigger until something killed it. Because of this, they could grow up to 4 and a half feet long (1.4 m). I love marine invertebrates with all my heart, but if I were wading in the ocean and I saw a huge, segmented flapjack sucking nutrients out of the sand, I’d be terrified.

So this very weird oval is, more or less, the pre-alpha version of a multicellular animal. It does everything an animal does, but barely. It moves really slowly and eats other organic matter. It grows in that animal fashion. Despite how little we know about Dickinsonia, it’s one of the most well-understood Ediacaran organisms. It paints a vivid picture of life before the Cambrian, and that picture, as it turns out, is unlike anything we could have guessed. Because of that, and because I hope to study the Ediacaran biota myself one day, Dickinsonia has a special place in my heart.

Before I go, I wanna apologize again for the gap in posts after the alleged end of my hiatus. I’m gonna go back to posting more regularly. Also, while I have your attention, thank you so much to the person who donated to me last week! I’m currently stuck in PayPal Hell, but I will get it eventually, and I appreciate it so so much!

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link