#ediacaran

I FINALLY finished part 1 of the Evolution of Life poster that I was doing for my class-

it’s been a passion project of mine- I wanted to attempt something like this outside of school, regardless. the history of life on earth has always fascinated me!

This first part shows the transition from simple life to complex life, and the move from sea to land.

I really hurt my hand making this, but I think it was worth it (:

Species: P. abyssalis

Etymology: “Comb of leafy branches,” after its shape

Age and Location: Ediacaran of Newfoundland

Classification:?Eukarya:incertae sedis: Rangeomorpha

Pectinifronsis a rangeomorph, and so broadly similar to Fractofusus,which also was a sessile organism that reclined on the surface, and with which it shared a presumed osmotrophic lifestyle and fractal anatomy. However, despite the simplicity of their body plans, there was still substantial variation between different genera. Pectinifronswas an enormous organism by Ediacaran standards, with the largest individuals being nearly a meter long. Unlike Fractofusus,which lay flat on the seafloor, Pectininfronswas taco-shaped, with its midline lying on the seafloor and two rows of fronds sticking upward. While superficially it resembled a folded Fractofusus, though, it appears to have grown differently: all Fractofusushave the same number of fronds and are essentially identical except for size, while larger Pectinifronshave more fronds. This suggests that Fractofususdeveloped an adult morphology early in life and simply grew by expanding itself, whereas Pectinifronsgrew by lengthening the midline of its body and growing additional fronds. Such a dramatic difference in growth strategies suggests that the rangeomorphs might be more diverse than previously thought. What kind of organism rangeomorphs are–or if they’re a single kind of organism at all–remains unknown.

Sources

Bamforth EL., Narbonne GM., Anderson MM., Bamforth EL., Narbonne GUYM., Anderson MM., Crescent S. 2008. Growth and Ecology of a Multi-Branched Ediacaran Rangeomorph from the Mistaken Point. Journal of Paleontology 82:763–777.

Hoyal Cuthill JF., Conway Morris S. 2014. Fractal branching organizations of Ediacaran rangeomorph fronds reveal a lost Proterozoic body plan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Species:E. plateauensis

Age and Location: Ediacaran of Namibia

Classification:?Eukaryaincertae sedis: Erniettomorpha

Ernietta is an iconic Ediacaran organism, and like most such organisms, its phylogenetic affinities are totally unknown, although like many other Ediacaran organisms, it may well be a stem-group animal. All we know for sure was that it was multicellular, but not apparently similar to any living multicellular organisms. A trait that defines the ‘erniettomorph’ body plan is a body The body of Erniettawas composed of essentially undifferentiated tubes of tough organic material. It appears to have lived mostly buried in the sand, with two fan-like fronds projecting into the water. Members of the genus seem to have lived together in large groups, perhaps as a consequence of their mode of reproduction.

Unlike all extant macroscopic organisms and like many other Ediacaran organisms, Erniettaprobably were osmotrophic–that is, they fed exclusively by passively absorbing nutrients from the water around them. This was possible as a result of its being essentially a sediment-filled bag, so that most of its body volume was actually just sand. The tubes that comprised the fan-like structures probably primarily served in osmotrophy while the others were structural and served to anchor the organism, however, there is no clear morphological distinction between different body regions.

Sources:

Ivantsov AY., Narbonne GM., Trusler PW., Greentree C., Vickers-Rich P. 2015. Elucidating Ernietta: new insights from exceptional specimens in the Ediacaran of Namibia. Lethaia.

Laflamme M., Xiao S., Kowalewski M. 2009. Osmotrophy in modular Ediacara organisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106.

I’m E X C I T E D to announce that the June edition of Scientific American features my art on the cover. The original image I did in 2016 has taken me places, so it feels right that the revamped version is helping an Ediacaran expert tell her story to the world.

Post link

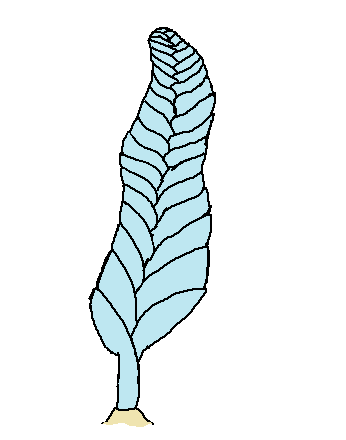

Charnia – Ediacaran (579-555 Ma)

I know what you’re thinking. One, this blog is supposed to be about animals, and two, the drawing today is really simple. To that I say 1) I’ll get to that in a minute, and 2) I have a big writeup today, because this is one of my favorite prehistoric creatures of all time, and I’m about to explain why.

So, today we’re talking about an organism called Charnia. It’s old. Really really old. It lived during the Ediacaran period, over 550 million years ago. That’s before the Phanerozoic Eoneven began. This is a Proterozoic organism, and boy howdy, is it weird.

Charnia was a fern-like creature that attached itself to the seafloor. We aren’t really sure how it ate. It lived in deep waters, so it wasn’t photosynthesizing. It probably either filter fed or absorbed nutrients directly through the surface of its body. It’s been theorized to have an unusual and very simple method of growth. Its cells may have multiplied in a fractal pattern, giving it a super simple body plan with very few bells and whistles. It looked a lot like a sea pen. Except, it’s not even closely related to sea pens. In fact, it might not be closely related to anything at all.

Charnia is a member of the loose collection of organisms called the Ediacaran biota. These were a bunch of simple aquatic organisms, who essentially came in two flavors: Fern and circle. And yet, they’re really, really important in understanding the evolutionary history of life on earth.

So, for a long time, it was assumed that the Cambrian Explosion was when multicellular life got its start. It was where we found our oldest recognizable animals. Every modern phylum could be traced to the Cambrian, and there was nothing but microfossils in the rocks older than that. Surely everything was microscopic until it suddenly and rapidly became big. Charles Darwin admitted the Cambrian Explosion was a big issue with his theory, and like I said when I covered Opabinia, some people thought the CE was God’s moment of creation.

But then knock knock, it’s Charnia, along with a bunch of other weird shit. Suddenly, we have multicellular life in the Precambrian, which was previously thought to be impossible.

I’ve been avoiding the word “animal” because they’re… probably not animals? There’s a lot of mystery around the Ediacaran biota. Even though they’re typically really well-preserved, they’re so simple we can’t really infer anything about them beyond “They’re really old and they aren’t here anymore.” We have no idea what they could have eaten, if any of them were capable of powered movement, all that. They’re completely baffling to us because there’s nothing else like them, alive or dead.

They may even represent a branch of the tree of life that isn’t around anymore. A completely separate experiment in multicellular life that never made it to this side of the Cambrian Explosion. Considering how utterly alien these things are, and considering they seem to have no descendants in the following periods, it’s entirely possible. It’s been suggested that, if fractal cell division was really how they grew, they were stuck with pretty simple body plans and were eventually out-competed as other organisms grew more complex.

Multicellular animals in the Precambrian cause a bit of a problem. If all this weird shit lived before the Cambrian Explosion, did the CE even happen? Maybe there was no big radiation. Maybe all of these animals had already been evolving slowly during the Ediacaran, and we just don’t have the fossils. Although, we don’t really have any evidence to support this idea, so take it with a grain of salt.

So, that’s a basic rundown of what we know about the Ediacaran. Or, I guess, what we might know about the Ediacaran. The field is basically scientists looking at rocks with circles on them and going “uhhhhh.” I don’t blame them, though. It’s not the scientists’ fault these things are so weird.

Post link

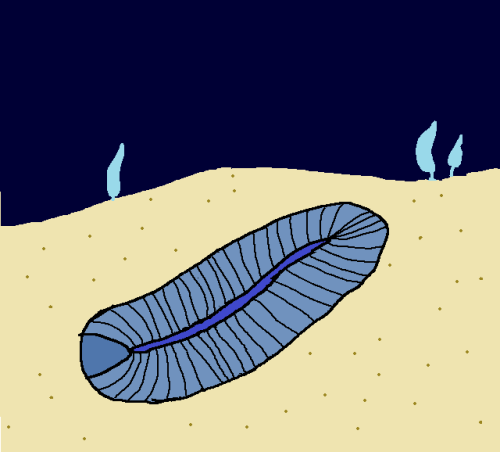

Dickinsonia – Late Ediacaran (558-555 Ma)

I may have been a little too quick to declare the end of my hiatus… But don’t worry, because I’ve got a lot to say about our featured organism today. We’re going back to the Ediacaran to talk about one of my favorite fossils of all time, called Dickinsonia. Its shape is a bit simplistic, so I gave it a little background, with some Charnia guest stars.

Like I mentioned last time, the Ediacaran biota are a loose group of super-ancient organisms who existed before the Cambrian Period, at the very end of the Proterozoic Eon. These are widely considered to be the first multicellular organisms, and lived during the second half of the Ediacaran period, in a span of about 40 million years. Many of these fossils come from the Flinders mountain range in Australia, where their squishy forms were preserved in exquisite detail, though they’re known from other locales too, like Newfoundland, the Ukraine, and England. These fossils are abundant just about wherever Ediacaran rocks can be found, which is really strange considering this was before the evolution of any hardened organic structures. Consider also that younger fossil beds like the Burgess Shale exist because something lucky happened to preserve everything. The Ediacaran biota are just kind of there. Why are there so many squishy organisms fossilized, and why in such detail? The most likely answer has to do with one of the hallmarks of this alien past.

The seafloor of the Ediacaran period was caked in squishy, lumpy carpets of bacteria or archaea feasting on the chemicals around them. These communities of microorganisms are called microbial mats, and although they were almost universal back then, they’re rare today. This is probably because animals who are really good at eating them evolved. If a microbial mat were to form in the middle of a busy reef, it wouldn’t be long at all before some fish or arthropod or something said, “Oh dunk, free food!” and ate it. That being said, they still thrive in remote waters that lack those predators.

So, the best explanation for the preservation of the Ediacaran biota are these microbial mats. They didn’t eat organic matter, so if something big died and sunk into the mat, the microbes covering it would unwittingly protect its impression from being covered by sand. Add a nice layer of sediment and several thousand years, and boom. Those softboys are preserved until subduction destroys the rocks forever.

So, anyway. What’s a Dickinsonia? Some sort of sea pancake? One of the trademarks of the Ediacaran biota is that we really have no clue what we’re looking at. Currently, their fossils are sorted into groups called morphotypes. A morphotype isn’t a real taxonomic division, but a method where organisms are grouped together based on their shape. So, you’ve got circles, and you’ve got fronds, basically. That doesn’t really mean anything though, because I could put snakes, caecilians, eels, and earthworms into the same morphotype—which I call Noodlemorpha—even though they’re all only distantly-related to each other. We just know that little about the lifeforms of the Ediacaran. Put all of that aside for a minute though, because Dickinsonia is special in that we actually know what it is, as of last year. After decades of postulating and debating, a conclusion has been reached. Dickinsoniais…

a bilateral animal.

Yeah, sorry, that’s it. We can’t really say anything else for sure. Still, that’s huge in the context of these organisms, most of which are so weird a new kingdom has been seriously proposed, called Vendozoa. To be able to identify one of them as anything definite is a huge landmark for the scientists who study these fossils.

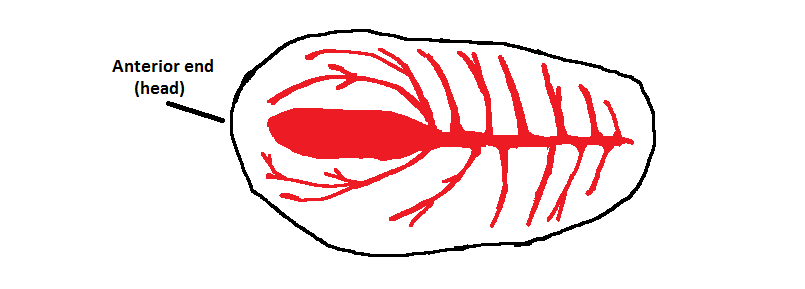

Dickinsonia lived on the seafloor. It crept along ever-so-slowly, and sifting food out of the sand and leaving trails of circular holes in the microbial mats beneath it. The segments on its body are called isomers, and might have been filled with organic fluids. t would have been very soft and flexible, like a segmented water balloon, but a bit thicker. It didn’t really have to be all that durable considering there wasn’t anything around to attack it. Some fossils even show impressions of possible muscle fibers, and a vein-like structure inside of its body, which some scientists have interpreted as a basal digestive system. It looked something like this, with the internal structure in red:

I really, really wanted to link to one of these fossils, but I wasn’t able to find any good pictures of the actual specimens. I can’t stress enough how absolutely extraordinary it is that a fossil this old might still show the internal organs of the thing that left it behind. We can guess a lot about the internal organs of things like dinosaurs based on similar animals alive today, but we’d have absolutely no idea what Dickinsonia looked like under the hood without these surprisingly detailed fossils.

Newly-bornDickinsonia looked like little circular pills without any isomers. We aren’t even close to ready to asking how this thing reproduced, by the way. Maybe it was like a sponge and just kind of spat its business into the sea and hoped for the best, but we have absolutely no idea. As the animal aged, new isomers grew from its posterior end, elongating its body. It grew throughout its entire life, getting bigger and bigger until something killed it. Because of this, they could grow up to 4 and a half feet long (1.4 m). I love marine invertebrates with all my heart, but if I were wading in the ocean and I saw a huge, segmented flapjack sucking nutrients out of the sand, I’d be terrified.

So this very weird oval is, more or less, the pre-alpha version of a multicellular animal. It does everything an animal does, but barely. It moves really slowly and eats other organic matter. It grows in that animal fashion. Despite how little we know about Dickinsonia, it’s one of the most well-understood Ediacaran organisms. It paints a vivid picture of life before the Cambrian, and that picture, as it turns out, is unlike anything we could have guessed. Because of that, and because I hope to study the Ediacaran biota myself one day, Dickinsonia has a special place in my heart.

Before I go, I wanna apologize again for the gap in posts after the alleged end of my hiatus. I’m gonna go back to posting more regularly. Also, while I have your attention, thank you so much to the person who donated to me last week! I’m currently stuck in PayPal Hell, but I will get it eventually, and I appreciate it so so much!

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link