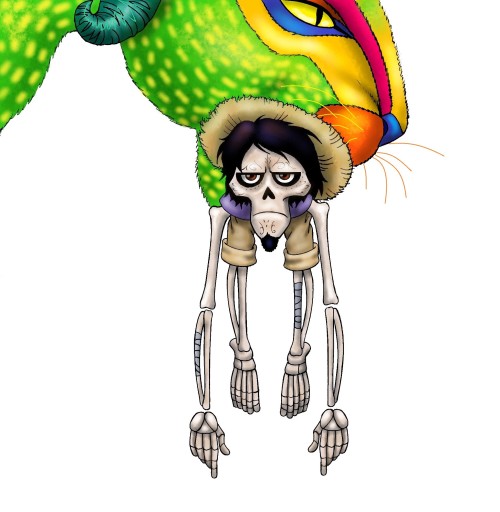

#pepita

A Coco (Pixar, 2017) Fanfic

written by @upperstories

Chapter 1 of 5 - Death Warmed Over

Miguel was no stranger to being grounded.

As well meaning as the boy could be, he was a magnet for trouble. Whether it was the occasional squabble with other kids at school, butting heads with a member of his own family, or simply getting himself into foolhardy situations– usually involving anything and everything musical– Miguel couldn’t count on both hands how many times he’d been grounded in his twelve years. Most of those times, he’d believed grounding had been an unfair consequence, that he had not been at fault.

But this time, Miguel did not argue. Did not whine about the injustice of it. Did not even bat an eye.

There were worse fates than facing an old fashioned Rivera-Brand Time Out.

“You know the drill, mijo,” said Enrique, Miguel’s papá, “No TV, no futbol, no Lucha Libre, no mu–”

“No music,” Miguel nodded, finishing his papá’s words when Enrique could not, as if rehearsed. Music was a given on being forbidden in the Rivera household, whether Miguel as punished or not.

But a small spark of something crossed his papá’s face. His father seemed to falter.

“…Well…” Enrique cleared his throat into his hand, eyes training to Mamá Coco’s bedroom door. He could hear his mother, Abuelita Elena, gushing to her mother, reliving memories that none of the other Riveras believed Coco could still recall. Hearing his mama be so happy, it was a sound he had not heard in many years, not unless it had to do with overcoming an exceedingly difficult shoe order. “No music… unless you intend on singing to Mamá Coco again.”

Miguel’s face, though slightly ashen and salt caked from dried tears, lit up. He sniffled and wiped his face, coughing a bit in spite of himself, overcome with relief.

The boy looked ready to topple over, as one would expect from a young preteen spending an entire night galavanting off to… Enrique had no idea where, but he did not feel the need to dwell on it. The idea of Miguel being alone on a holiday meant to be spent with your familia left him feeling like a rock was lodged in his stomach. A rather spiky one at that.

“A month sounds fair,” said Miguel, voice cracking from emotional fatigue, Enrique assumed.

“…How about just a couple weeks?” said Enrique, patting Miguel’s shoulder, “One week if you’re good.”

Miguel almost laughed as he stumbled into Enrique’s side, making the man jump. He caught Miguel and pulled him into a hug, to which his son gladly, if weakly returned. Enrique felt his chest tighten, trying his best not to imagine all that Miguel had gone through in the past twelve hours. Though his son had refused to share every single detail of all that had transpired during Dia de los Muertos, he’d told Enrique that he’d spent it in De la Cruz’s tomb. A night in the cemetery was no place for a child, especially with the chill in the November air, and–

And…

Was Miguel shaking?

“Mijo?” Enrique said, ruffling his son’s hair, eyebrows furrowing at how warm his son’s head felt. Was he running a fever? “You know we’re not angry at you anymore, yeah? Is everything ok?”

“J-just,” Miguel croaked, smiling tiredly up at his face as he continued to cling. Miguel hadn’t clung to Enrique since he was young enough to believe in monsters under his bed, to cry over being teased by his older cousins. And he was shaking. “A little c-c-cold. And t-tired.”

“Well no wonder…” sad Enrique, feeling the light fabric of Miguel’s shirt, “You’re soaked to the skin and– mijo? What happened to your jacket? The red one you were so fond of?”

Miguel choked on his words. For a moment, Enrique was worried he would run again, and his heart fell. Miguel hugged him tightly and his his face.

“I-I lost it, papá,” said Miguel, shakily.

“Where?”

“In the… I-In the graveyard?”

Enrique gave Miguel a look that only a father could give to a wayward son. It was a pretty darn good one too, as the boy was having a hard time keeping eye contact.

“S-sorry.”

Enrique opened his mouth to argue, to scold Miguel for telling a lie, and a rather poor one to boot. To claim that, as small as Santa Cecilia was, the cemetery was hardly a big enough place to lose a jacket. To tell Enrique the truth, the whole truth.

But one look at his son, who had already gone through enough stress from their family’s overbearing superstitions of music, who had openly cried and buried his face into his papá’s chest upon returning home (mind you, after nearly scaring him and his mother to death), who had returned Mamá Coco’s long-buried memories of a man who everyone, even Elena had grossly misunderstood, and all the fight to scold his boy had flown out of him. Enrique could only sigh, left to realize just how tired he felt after a full night of searching for his son.

“Come on, mijo,” said Enrique, gently rubbing Miguel’s back and leading him to the extended household that he and his brother’s family shared, all of it interwoven with the Rivera workshop. “Let’s get you to bed.”

“Do–” Miguel coughed, roughly, then sniffled. “D-don’t I need t’get re–ready for school?”

“I think after the night you’ve had, you can afford to miss one day,” said Enrique. “Besides, you think we’re about to let you out of our sight after pulling this stunt?”

Miguel actually laughed, surprising Enrique, the snickering only interrupted by more coughs.

“I-I guess not, papá.”

Miguel’s room was as sparsely furnished as the rest of the Rivera household. A single bed, a chest of drawers, some photos on the wall of small, sweet moments with friends and family. In spite of the lack of furniture, it was still very much Miguel.

Dirty clothes littered the floor in spite of his mamá’s many attempts to get the boy to clean his room. Posters of Miguel’s favorite luchadores were taped to the wall, action figures strewn about, bed left unmade– and now that Enrique was looking with a more aware, critical eye, he spotted a borrowed toolbox under Miguel’s bed, haphazardly hidden by unmade sheets. Enrique tried not to imagine what the boy intended on using it for, though it probably had something to do with the makeshift white guitar his son had frankensteined under his family’s nose. The boy’s wastebasket was also filled with crumpled pieces of paper, a blank notepad and pen on his bedside table.

Trying to put thoughts of guitars and graveyards out of his mind, Enrique led Miguel to his bed, quickly unmaking and remaking it before helping his son climb in. Dios, the boy looked beat. He hadn’t even bothered to take his shoes off.

“Are you sure you’re just tired, mijo?” said Enrique, placing the back of his hand on Miguel’s forehead, pushing the boy’s matted hair from his face. He felt far too warm.

“Mmmhmm,” said Miguel, barely awake. He was already burying his face into his pillow.

“Miguel?” said Enrique. “At least change into some new clothes before going to bed, huh?”

“Sí, papá…”

“…Miguel?

“…”

Aaaaaand the boy was out.

For a moment, the exhaustion of the night crept up on the father, and poor Enrique was so sorely tempted to simply turn around and call it a day. But, well, a father was a father, and no matter how much he knew Miguel would complain about being fussed over, he was not about to let his boy sleep in damp clothes from yesterday.

For the first time in many years, Enrique helped Miguel untie his shoes and change his clothes. He even helped Miguel under the covers and tucked him in, giving the boy’s dirty hair a tousle. In spite of nearly turning thirteen, Enrique had almost forgotten how young his boy still was. So young and foolish and careless…

And very brave. Brave enough to do what neither he, nor Berto, nor Gloria nor any of the Rivera men or women had ever managed to do in their longer lifetimes. Change Elena’s mind, and make Mamá Coco smile like the sun.

Ah, yes. He could reprimand the boy about his carelessness later. For now, Miguel needed rest. The entire family did. He was grateful that most businesses were closed following Dia de los Muertos, as Enrique planned on spending the next few hours surrounded by his loved ones, soaking in the glow that could only have been described as a miracle.

As Enrique made his way back to the family’s hacienda, a familiar stray Xolo shambled its way clumsily across the courtyard, covered in stray marigold petals and yapping up a storm. His enthusiasm nearly gave poor Carmen a heart attack. Enrique recognized the pooch immediately as the raggamuffin mutt who followed Miguel around town, begging for scraps. The boy’s very own clumsy shadow.

Before Enrique could think to shoo the Xolo away, he heard the telltale whap of a chancla smacking a palm, and froze. He noticed movement new Mama Coco’s room and turned to find his seething, broiling mother, a petrified Berto standing right behind her. Their childhood had taught the Rivera men well, not to stand between their mother and the object of her wrath when a shoe was within reach.

“You,” growled Elena, pointing her chancla at the hairless mutt.

Dante barked, lips pulled back in a smile, long tongue lolling out in complete innocence. The poor mutt apparently could not see his end staring him right in the muzzle.

Elena marched right up to the pooch, hands on her hips, and glared down at the poor, unsuspecting dog.

Dante, as Miguel had named him, wagged his tail, standing at attention (or… at least as attentive as one canine would look with his long tongue nearly hanging to the ground).

“And just where have you been, eh?” said Elena. “Your boy goes missing for a full night and what help were you? Pah! Rolling around in some trashcan all night, I bet.”

Dante tilted his head, and for a moment Enrique thought that the pooch had finally grown some sense and was about to book it to the nearest alley. But then the Xolo simply snorted in response, and trudged forward to lean heavily into Elena’s legs, leaving dust and drool all over her skirt and apron. Enrique saw Berto cross himself, honestly looking afraid for the dog’s life.

But when mamá did not move to slap him with her shoe, Enrique knew that Berto had nothing to fear. The exhaustion, both emotional and physical, washed over her face, and she put the shoe away. Enrique almost laughed. It was not often that his strict mother’s heart was melted and her weapon shieved, but perhaps in light of recent events, poor Elena’s heart had finally lost some hardness.

Dante’s head swiveled the door leading to Miguel’s room and yapped merrily, oblivious to Elena’s frustration.

She sighed and nodded.

“Go make yourself useful,” said Elena, patting Dante’s head and motioning to the door. “Keep that boy company, mutt.”

Though Enrique knew better than to assume that this dimwitted dog could understand anything beyond the words “food” and “fetch”, Dante pounced in place, barked, and dashed off to Miguel’s room. Like a dutiful soldier.

The family collectively winced when they heard a crash, possibly of the dog running right into a wall.

A very graceless, clumsy… dutiful soldier.

—–

Héctor was no stranger to waking up in peculiar places.

The life of a vagabond had warrented him as many freedoms as it had setbacks. No home real home meant no real curfew. No one to tell him where to go or how to dress led to the opportunities to wander and cause trouble to his heart’s content. No one to look out for him, to keep him in mind, to care for his well being and safety led to night after night, drinking to (ha) forget. No one to tell him to stop when things went too far.

He couldn’t count on both boney hands how many bars he’d been thrown out of. How many gutters he’d awoken next to. How many outraged unfortunate neighbors had shooed him off of their front steps with brooms, or porches with spatulas, or window sills with chanclas (Héctor still had no idea how he’d gotten into Leon Hernandez’s window ledge hanging garden, but he could only assume that the empty tequila bottle lodged in his ribcage had everything to do with it).

But this time was different. This time, Héctor did not awaken to a cork painfully lodged in his eye socket or the smell of booze on his bones. He was not lying prone, held together by his suspenders and luck on the far edge of town. No one was screeching at him to get lost, to get off their property. From the smells, or rather– the lack of smells, he did not think he was even in his ramshackle hut in Shantytown.

He was… somewhere warm. Some place soft. A place that held no intent on kicking him to the curb or hauling him off by his bootstraps. Sounds were muffled and quiet, though he could hear footsteps come and go past whatever room he was in. They echoed faintly, making him wonder how big the room was or how high the ceilings were. He could faintly feel sunbeams gently falling over his side, from a window perhaps? It all felt strangely, almost achingly familiar, like the room he and Imelda had shared when he was still alive–

Ah.

Yes.

So that explained it. He was dreaming of Santa Cecilia again.

He always did after Dia de los Muertos. Héctor couldn’t quite remember a time he did not dream of his hometown, but the dreams that followed him after the holiday, usually in a dazed, drunken stupor, were the ones that acted like the strongest balm. If he could not cross the bridge of orange petals, stand on the earth with his own two feet, small the oh so missed scents of tarragon, flowers, earth and stone– and yes, even the livestock– then by god, he could at least pretend. Pretend that everything had been a dream, that one day he would awake in his own bed to the sleeping face of his young wife, to the faint giggling of a little girl padding her way across the covers, the welcome sights and smells and sounds of home.

Héctor smiled, settling deeper into the covers.

Up a bit early today, aren’t we, mija? He wanted to say.

Tengo hambre, papa! Coco would whine.

He could almost feel her settle on his chest, gently shake him with her small hands. He wanted to reach up and cup her face, but his arms refused to move. Too tired. Too worn from the horrible, horrible nightmare.

Well, we cannot have that, a voice would say to his left.

Héctor felt his heart lift when something warm pressed up close to his side, smelling of sleep and cat hair and chicken feathers. No matter how often Imelda scrubbed, she would never be fully rid of the smells of a farm, as neither would Héctor of wood, stale clothes, ink and parchment. The smells of professions stuck with you that way, but Héctor did not mind. He preferred cats anyway.

How about huevos rancheros? Imelda would say.

Huevos! Huevos! Huevos! Coco would cheered, jumping up and down on Héctor and shaking him to more wakefulness.

Díos, this is some dream, Héctor thought. For a moment, he could feel something very heavy, shaking his chest. Pressing down. Getting heavier. How much had Coco grown in the past months he’d been gone?

Héctor tried to move his arms to lift Coco off of him, but they remained pinned to his sides. The pressing feeling was starting to spread to the rest of his body, keeping him rooted in place. Almost as if he were trapped under a rock, rather than wrapped in tight, clean sheets. The pressing turned to burning, burning in his chest and throat, and Héctor felt panic rise in him.

Why couldn’t he move? What was going on? Where was he?

The warmth from before, once sweet and caressing, turned to stifling, suffocating. Héctor couldn’t move, couldn’t breath. Almost as if…

Almost as if her were buried, deep underground. As if he were in a grave.

No.

No no no, please no.

He could not be dead. He was so close, dreaming sweetly of breakfast and tiny hands and smiles and miles away from the nightmare of the truth. That his best friend from childhood, his hermano had taken his life, that he’d spent so many decades alone in death. That Imelda had died angry and Coco had lived without knowing a father. That he’d failed time and time again to return to the small town he’d dreamt of returning to, time and time again.

Héctor wanted to scream, but his aching throat would not let him. He tried to open his mouth, to call for help, but the burning only became worse, and when he coughed, he felt the pressing intensify. His arms, so heavy and aching, could not move, and now entire body felt like it was on fire. His eyes felt as though they’d been glued shut, his head began to pound, and the soft haze of sleep gave way to dizziness. Were if not for the fact that he lacked a stomach, Héctor was certain he was going to vomit.

He felt something in his chest– a small rib bone, fractured– slip out of place, and choked out something that almost sounded like a word. His throat exploded in pain, and he prayed for anything to end this nightmare. Even the Final Death would have been a mercy.

“PEPITA!”

A voice screeched, reaching Héctor through the wave of pain that had drenched him, and his eyes finally flew open. He was met with blindingly brilliant colors, greens and reds and oranges, far too dazzling for the first sight of his streaming eyes (when had he started crying?). But the most brilliant were the yellow, gleaming, judging eyes of an alebrije. Imelda’s alebrije, large, commanding, terrifying, and lying completely on top of him.

“Get off of him!”

The alebrije’s large head perked and swiveled, cat-like at the skeleton standing in the doorway. Héctor almost didn’t recognize her, but even with her hair down in a single braid, and her regal purple gown exchanged for a white, embroidered camisa and red skirt, there was no mistaking Imelda Rivera, in all of her enraged glory. She was covered in leather shavings and wearing a pair of work gloves, and in one gloved hand, she shook an unfinished boot at the large creature, like a soldadera brandishing a sword.

“Shoo! Shoo! ¡Hechate!” Imela screech, “Get down, right now!”

With a defiant, almost annoyed rumbling growl, the spirit guide cowed under her mistress’s anger (the shoe, in particular), and crawled off of Héctor. The burning feeling finally gave way, and he took a deep breath– but he regretted it almost immediately, as the cool morning air scratched and tore at his throat in a way he had not felt since living– and was launched into a whooping cough.

Imelda dropped her shoe and was at his side in an instant. He felt her small hand gently pressed to his skull, pushing his matted hair away from his face. Her cool bones were a relieve against his skull, which felt as though someone had used it for a spirited game of futbol.

“Im–” He croaked, still hacking up a lung he did not posess, “Imelda–ha–?”

“Shhh, shh, wait for it to pass,” Imelda instructed, strict, yet tenderly. “Breath, breath…”

Once he’d finished giving his ribs a thorough workout, Héctor tried taking smaller, more even breaths. Díos, he felt awful. Like that time when he was a young boy, and caught a terrible cough from playing in the rain. He felt as though his nasal cavity had been stoppered, and his ribcage and the vertebrae along his neck burned, as if he’d swallowed several habañeros. The rest of his body hurt when he tried to move it, like many thousands of pins and needles poking his bones from the inside out, and everything else felt so heavy and hazy. Had he still been able to, he was certain he’d be sweating through the soft bed sheets he’d been wrapped up in.

“There. Easy, muchacho, easy,” Imelda crooned, placing her other hand on his chest.

He wanted to move his hand on top of her, but found he could not. Whether this was because of the pain or because his instincts still warranted trepidation with romantic contact with her, he had no clue. He couldn’t remember a time when he’d been cared for with such tenderness, and instead leaned his face into her other hand when she moved it to his cheekbone. He tried to focus on breathing, not sure what to say to his former beloved. Not sure he even could say anything with his throat feeling all torn to shreds.

Imelda, skull pinched in fretfulness, annoyance, and the faintest of fondness, snapped her head at Pepita and pointed at her, accusingly.

“I told you to keep an eye on him, not smother him!” she snapped. “You could have broken a bone. Ay, Díos mio, as if he doesn’t have enough of those!”

Pepita growled again, and Héctor could swear he heard something akin to a mewl.

“Don’t apologize to me!” said Imelda, “I’m not the one who was crushed under three hundred fifty pounds of fur and feathers!”

Pepita’s ears fell back. She lied down, bodily on the ground– and it was then that Héctor realized that the room must’ve had a rather high ceiling to accommodate such a large creature– and she rolled onto her back. She growled in a loud, purposeful purr. Héctor wished so desperately that he could laugh at the alebrije’s attempts of endearing herself Imelda, all of its intimidating swagger flung out the window.

“Don’t you try to butter me up,” said Imelda. “It never works.”

Pepita purred louder.

“Don’t,” Imelda warned.

Pepita purred louder.

“Pepita!” Imelda snapped, though it was clear that her resolve was slipping.

The urge to laugh at the absurdity of the scene, a small, stern woman treating such an imposing creature as one would a housecat, all became too much for Héctor and he choked out a laugh– one that sent him into another painful fit of coughs.

Imelda fell silent, all of her anger snuffed out, and with a sigh, she simply shooed Pepita to the veranda– with a perch for some time-out time– and returned to Héctor’s side. She smoothed out the sheets as she waited for him to settle, the poor man groaning in pain once the coughs subsided.

“What…” Héctor wheezed, voice rougher than sandpaper and almost gone, “What ‘appened? Where… where’m–?”

“Don’t talk,” said Imelda, “Save your strength. Here.”

Previously unnoticed, Héctor watched Imelda as she turned to a table next to the large twin bed, and poured water from a metal pitcher into a clean white cloth. She wrung it out over a pan and then gently placed it over his brow bone. The coolness eased the throbbing headache, and he sighed in relief, glass eyes fluttering closed.

He felt her hand press to his cheekbone once more, and pressed his face into it with more certainty than before. Were it not for the ache in his bones and the fever, feeling her run a thumb along the ridge where his upper jaw met his lower one would have felt like heaven.

“Thank you,” he croaked.

“Mmmm,” Imelda hummed, softly.

A silence fell over the both of them, and Héctor simply waited it out. There was so much he wanted to say, so much he wanted to be said, but he knew better than to interrupt the silence. For everything that Héctor wanted to tell Imelda, he could feel that she had so much more to say.

“You look awful,” said Imelda, though she held no bite in her voice, as if stating a fact rather than making a scathing remark. “How do you feel?”

Héctor tried to speak, but his voice could barely break a whisper. Why did everything hurt so much?

“Like death warmed over,” he said.

“That’s not funny,” said Imelda. She sounded angry. \

“Sorry,” said Héctor, smiling in spite of himself, “But it’s the truth.”

His smile fell when he felt thin, warm bones carefully encircling him. He opened his eyes and found himself looking at the side of Imelda’s head, which she was pressing into his collar bone like a lost child to her mother’s skirt. Her boney fingers clenched the sheets. She was shaking.

“Imelda–?” Héctor croaked, the space in his ribcage where his heart would be giving a fearful jerk.

“You were gone, idiota,” Imelda said into the sheets. Héctor could not see her face, and he was thankful. From the sound of her voice, broken and forcing itself to be held together, would have been worse than any of the pain he felt right now. “You almost… you were dust.”

Héctor’s eyes widened. Memories from before were fuzzy, warped, fantastical and difficult to grasp, like smoke. He recounted… a boy, a small, living with a smart mouth, a dog, a competition, Ernesto. Things trickling back in, little by little, until Héctor finally recalled the empty, cold feeling settling over his bones and drawing all of his strength from him. Of being tired. Of feeling something he’d feared for nearly a century.

“The… the Final Death?”

“The Final Death,” said Imelda. She did not move from the embrace, nor did she stop shaking.

And that’s when everything fell back in a rush. Miguel and the photo, the Sunrise Spectacular, Imelda’s singing, nearly losing his little chamaco to a great fall, and then sending the boy home just in the nick of time. The creeping emptiness overtaking his bones, being unable to move in Imelda’s tight, desperate embrace, and everything going white.

“Oh…” Héctor croaked, numb with shock. He’d survived. Somehow, some way, his wreckless little great-great-grandson had resurrected the memory of the wayward musician from his pobrecita.

Just as he was about to become dust in his poor wife’s arms.

Héctor’s arms ached to return her embrace, but alas they still would not listen. He could only settle for pressing his face against hers, grateful that their cheekbones somehow messed together, and did not clack. They fit, like a couple puzzle pieces, and Héctor only focused on Imelda’s and his own breathing. This feeling, this fitting, gave him a whole new feeling, not one of emptiness of burning or aching, but a warm, melancholy belonging.

For the first time in so long, it almost felt like home. Not just a pretend kind from one of his dreams, but a safe, warm, home.

“I’m… I’m sorry,” he croaked.

“I know,” said Imelda, her voice tight and muffled.

“I… I think I’m going to be saying that a lot,” he said, almost laughing, “I have a lot to be sorry for.”

“Don’t,” she said, settling deeper into the hug. Héctor nuzzled her hair, and was overjoyed beyond words to realize that she still smelled of cat hair and chicken feathers, in spite of the overpowering leather from her shoemaking. “You’ve apologized enough. Just be quiet and let me…”

Héctor did not understand what she meant at first, but when he felt her head move, the strange sensation of teeth and jaw clacking gently against his temple, Héctor went stiff.

She’d kissed him. She’d swallowed her pride, her anger, her fear, all of the many emotions his beloved had felt so strongly in life and death, and kissed him.

He hadn’t been kissed since he left home.

“Don’t you ever,” said Imelda, her voice low, threatening, with a touch of possessiveness, “Leave home again.”

Imelda sighed and settled back into the hug, her shaking finally subsided. Héctor, breathless, staring wide eyed at the ceiling above him, wished the moment could last for eternity. He fought as hard as he could against the wave of relief, of utter exhaustion as it creeped its way through him, the warmth of the embrace lulling him. He couldn’t fight it off forever, but damn if he wouldn’t try.

“Claro… I’d like to see someone… try to make me leave again,” he breathed, nestling into the feeling as exhaustion finally took him.

The last thing he heard from Imelda humming a soft tune, and Pepita purring loudly in time to her song from her perch on the veranda.

And for once, he needed not dream of returning home.

He already, finally, was.

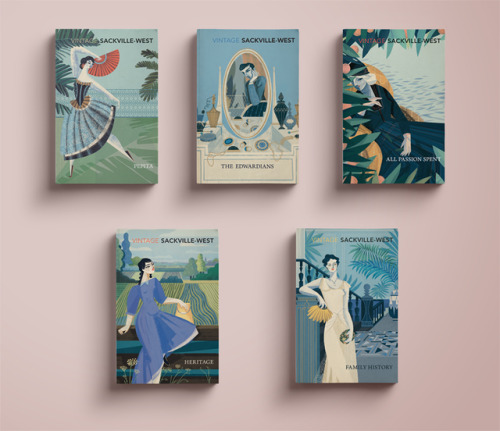

All of the covers I’ve had a pleasure to draw for Vita Sackville-Vest’ novels.

Vintage Books

Penguin Random House

Art Direction: CMYK Vintage Design

More info: https://goo.gl/eQsMC7

© GOSIA HERBA 2017

Post link