#permian

Diplocaulus- Early-Late Permian (~270-245 ma*)

Our second Permian animal, and our first definite-absolute amphibian, is Diplocaulus, a 3-foot long predator from Texas, and maybe Morocco. It’s… super weird and I feel very strongly about it.

For the most part, Diplocauluslooked and acted pretty much like a Giant Salamander. It had a sprawling, four-legged gait. It spent most of its time in the water hunting fish. It lived and reproduced in burrows near lakes or other bodies of fresh water. It weighed about 5-10 pounds, as much as a cat.

Anyway, let’s talk about that head. It’s shaped like a boomerang because… It just happened like that? The problem with extinct animals is that the farther back in the fossil record you go, the less information we have on them. But no, everything under natural selection happens for a reason, even things as ridiculous as this. Maybe it served as a hydrofoil, letting it swim faster. Another theory is that it was shaped so awkwardly so nothing could swallow it. I like that one. It was definitely hard to lug around on land, though. They can’t all be winners.

We also have fossil evidence that Dimetrodonwas a frequent predator of this soggy boy. One set of remains looks like a crime scene, where a Dimetrodondug up a burrow and ate some young Diplocaulus. This maybe says that Diplocaulustook care of its young beyond squeezing them out and walking away, but maybe it’s best not to read too much into it. Maybe they all just holed up in the ground together during the dry season.

Diplocaulusis unique within its group, the Lepospondyls. Lepospondyls were one of the oldest groups of amphibians, and were characterized by simple backbones, which were basically just the primitive notochord wrapped in bone. Diplocaulusis one of the largest in that class, as well as the youngest, living well into the late Permian. It’s also the only one we know of that looked like a banana. The placing of Lepospondyli is a little up in the air. We’re not sure if they’re the early ancestors of modern amphibians, or if they’re directly descended from the earliest land vertebrates, or what.

For some reason, it’s been the subject of a number of hoaxes claiming it’s still alive. Seriously, google ‘diplocaulus real’ and you’ll find so many pictures and videos of people trying to say they saw one. I don’t know why this keeps happening to Diplocaulus, of all animals, but it does. Maybe because it’s small and easy to fake? It’s also appeared in pop culture a few times, which is kinda strange for something of this sort. It’s in ARK: Survival Evolved (Basically in name only. It’s REALLY big and REALLY angry-looking), as well as a few Jurassic Park games (again in name only). It also shows up briefly in the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion, which I only mention because I like NGE. It’s only there for like, a second in the last episode. I can’t offer any further context, because it’s the last episode of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Diplocaulushas always had a special place in my heart. When I was a kid, my grandparents gave me a bunch of books about Dinosaurs that belonged to my dad when he was young. One of them was titled Prehistoric Monsters did the Strangest Things. It’s from 1974, and the cover literally has a bunch of sauropods standing in a lake munching on seaweed, so that should tell you everything you need to know about the accuracy of the book. I still ate that shit up. Diplocaulusis the animal they use to talk about the transition from sea to land (on this spread right here). I stole the color scheme, because in my head it’s always been yellow.

*There are no exact dates for Diplocaulus’ span of existence, so I snowballed it from the beginning of the Permian to a bit before the Great Dying. If I’m wrong, and there are dates for it, please let me know!

Post link

Helicoprion- Middle Permian (290 Ma)

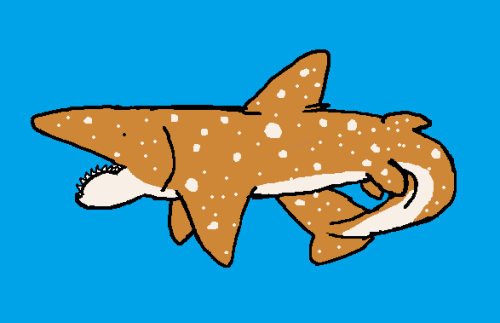

For someone who loves fish as much as I do, I rarely talk about them here. This is only the third fish I’ve drawn for this blog, and this one wasn’t even my idea. This animal was requested by @mrultra100, who also suggested the color scheme! This one was really fun to research and pretty challenging to draw (in a good way), so thanks for the suggestion! This was a widespread, cartilaginous fish found on every major continent except Africa and Antarctica. This was prime Pangea time, so there was really only one ocean anyway, the Panthalassa. Even though it looks like a shark, it belongs to an extinct order called Eugeneodontida, whose closest living relatives are chimaeras. That’s why the color scheme is based on the spotted ratfish.

The most famous and immediately different feature of Helicoprion is the tooth whorl in the lower jaw. Almost all Helicoprionfossils consist of only these swirly teeth, and a lot of what we know about its appearance is based on its relationship with ratfish and an extinct cousin called Ornithoprion. Since there’s absolutely nothing else with a sharp swirly thing on it alive today, it took a long time to figure out what we were looking at when we dug them up. In the past, it’s been suggested as:

- A part of the upper jaw, curling up over the snout.

- The end of the tail, normally curled but could be lashed at predators.

- A really weird dorsal fin as some kind of defense. Not a very good one, but still.

- The lower jaw, curled downward out of its mouth.

The last interpretation was considered correct for a long time, until partial remains in 2013 revealed it was contained entirely in its jaw. This version looks really really cool and I almost considered drawing it like that instead, but that would be a betrayal of my mission statement, I think. On the plus side, that means this was a much bigger animal than we thought. We have no direct evidence of the shape of its body, but if our estimates are right, it could have been up to 30 feet long. That’s bigger than any non-filter feeding shark alive today.

Since we don’t really know what the whole fish looked like, we can only guess what it used the tooth whorl for, exactly. We know that teeth would grow on the end towards the throat, pushing older teeth into the spiral. We think these were the only teeth in its mouth, and that it used this line of teeth to crush prey against the roof of its mouth. Back when we thought things had to go extinct for a reason, we thought Helicoprion died out because the tooth whorl was too unwieldy. Even though this theory was unpopular long before we knew where exactly the whorl was, knowing that it’s definitely inside its mouth completely discredits the idea that it was too clumsy.

Everything we know for sure about Helicoprion shows how jury-rigged every living animal on earth is. The spiral of constantly growing teeth sounds absolutely ridiculous, especially compared to modern cartilaginous fish whose teeth are arranged like we’re used to, and just replace themselves when they fall out. The tooth whorl evolved in Helicoprion because, well, it was clearly doing something useful for it. There are other, seemingly more straightforward ways to go about crushing things with your jaws, but this lineage just happened to have a string of circumstances (or lack of circumstances) leading to the infamous swirly mouth. We can’t say for sure why that is. Natural selection is complicated, and not everything evolves because it helps something survive. Plenty of traits evolve because there’s no pressure against that trait. Other traits evolve because of the mating preferences of female members of a species. There are a lot of potential reasons for the tooth whorl, but something as unusual and derived as this likely evolved because it served a good purpose.

That’s about it for this mysterious fish. I hope I did a good job, it’s not every day I get a recommendation, and I wanted to go all-out! I did what I could with our limited understanding.

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link

Lystrosaurus – Late Permian-Early Triassic (255-250 Ma)

I’m back! I was sort of at a loss of what animal to talk about when I came back from my hiatus in earnest, but during the spotty downtime I had last week, I read When Life Nearly Died by Michael Benton, and that pointed me in the direction of this chubby little gentleman, whose name is Lystrosaurus.Lystrosaurus is one of the (very very VERY) few animals to survive the Permian-Triassic Extinction event, and we’re gonna take a look at why exactly that is.

Lystrosaurus is yet another synapsid, or proto-mammal. This guy was a member of the second wave of Paleozoic synapsid radiation, a member of the order Therapsida, which were characterized by being more similar to true mammals than the first group, the pelycosaurs. EdaphosaurusandCotylorhynchuswere both pelycosaurs, and were a bit more basal. Lystrosaurus shows a few of those therapsid traits, most importantly the shape of its skull and its semi-sprawling gait. On the less mammalian side of things, it probably had a beak made of horn for shearing vegetation. It had the characteristic deep body cavity for digesting all the tough plants it ate. It also had no teeth except for a pair of enlarged canines, which it probably used to uproot its food. The most common species was about the size of a schnauzer, although a much rarer species grew a bit larger. All-in-all, it wasn’t really anything special compared to its contemporaries.

Despite being tiny and rather typical of an animal from its time period, Lystrosaurus is an important animal for a few reasons. Even though plate tectonics are common knowledge and accepted as fact now, it took a long time for it to gain any serious traction. Alfred Wegener was pretty much laughed off when he first suggested the continents move in 1915. As a part of this theory, Wegener also suggested the continents had been united at some point into a supercontinent he called Pangea. His contemporaries heard the idea and basically said, “Okay but continents don’t move, obviously. Have you ever seen a continent move?” To their credit, the evidence at the time was, more or less, Africa and South America fitting together and other such things. Which, yeah, we know were right now, but back then it wasn’t so obvious. The next several decades were a slow march to acceptance of the theory of continental drift. Lystrosaurus figures into this by having been found in Asia, Africa, Europe, and even Antarctica by the 70s. At that point, even the most hardened skeptics shrugged and said, “Okay, yeah, fine.”

Lystrosaurus is known from an absolutely stupid number of fossils. The Great Karoo Basin in South Africa has an unreasonable amount of Lystrosaurus remains. They make up 95% of the animals found there, and they’re so abundant that paleontologists pull their hair out trying to find literally anything else. The most studied parts of the Karoo Basin span the late Permian and Early Triassic, and once you get into the Triassic rocks, it’s pretty much Lystrosaurus all the way down. Why is that?

Because nothing else survived the Permian Extinction.

There are five major mass extinctions in the Phanerozoic Eon. I’ve talked about two of them on this blog so far. I talked about the End-Ordovician extinction event when I covered Endoceras, and the End-Triassic extinction with Effigia. And I’m here to say that those events were fucking peanuts compared to this one. This was the single greatest crisis for life on earth, to the point that it’s often called The Great Dying. This was the destruction of about 90% of all species on earth at the time, and for a while we weren’t even really sure what was causing everything to fucking die. The most accepted theory nowadays is the series of eruptions of the Siberian Traps at the end of the Permian period. Basically, most of what we now call Siberia turned into a volcanic wasteland and exploded every so often, anywhere from every few thousand years to every few months.

These were more than volcanic eruptions. This was fire and brimstone, magma punching massive holes in the earth and launching toxic gasses and solid ejecta into the atmosphere. Anything remotely nearby suffocated or was struck by fiery debris. This wasn’t the most severe killing agent, though, not at all. The Great Dying earned its name because of the secondary effects. The gasses spewing into the atmosphere blocked out the sun and caused flash-freezing, followed by periods of global warming. Glaciers melted and released even more toxic gasses trapped beneath them, poisoning the seas and killing anything unadapted to anoxic conditions. It’s pretty telling that the majority of the marine animals that survived into the early Triassic were clearly adapted to life without plentiful oxygen. Plants on land were suffocated or frozen to death, and the ecosystems collapsed from there. The earth was a frigid, barren landscape. The seas and land alike would be littered with corpses of animals and plants. The earth has mechanisms to balance these influxes of toxic chemicals, but the problem was that by the time those mechanisms could get started, Siberia would erupt again and start the process all over again. If you were to walk around Pangea during the peak of this crisis, 1) It would fucking suck, and 2) You’d probably come across a very distressed Lystrosaurus before finding any other animal.

Why in the goddamn hell did Lystrosaurus survive when so many other animals didn’t? It’s a complicated question, because it’s important to ask another question first: What animals are vulnerable to extinction events? There are a couple of broad categories of vulnerable animals during mass extinctions:

Large animals: Large animals are especially vulnerable because they need more energy to keep themselves going, and almost always have small populations and slow reproductive cycles. This goes for predator and prey alike. When plants start dying, herbivores can’t feed themselves, and the large carnivores that prey on them don’t have anything substantial to eat. This is the reason animals like elephants and rhinos have such a hard time bouncing back after we nearly hunted them all to extinction.

Specialized animals:Specialized animals are almost always doomed in big extinctions. If an animal is really, really good at functioning in a specific environment, it’s going to bite it as soon as that environment gets thrown off-kilter. Animals that specialize in eating a specific plant or hunting in a specific environment don’t usually survive when everything gets hit.

So, the animals who are most likely to survive a mass extinction are the small generalists, who can thrive pretty much anywhere. Lystrosaurus fits this description, but forget all of that for the purpose of this conversation, because the Great Dying decimated life of all sorts. Generalists were more or less just as likely to die off as the specialized animals or the big guys. So, we ask again, why did Lystrosaurus survive when so many other animals, even those similar to it, didn’t?

There isn’t really an answer to that question. Scientists have puzzled over the remains of Lystrosaurus and asked over and over again, “Why this little bastard?” and they’ve come up with nothing substantial. It was luck that a little beaked herbivore was one of the lucky few. There’s no adaptation that made it particularly hardy in the face of total metazoan annihilation. There’s no reason it survived the act break between the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras. It just did because it happened to survive. This isn’t a parable of survival as much as it is one of dumb luck. One of the characteristics of a mass extinction is that it is essentially indiscriminate. Lystrosaurus had every reason to perish like its relatives, but it just didn’t. Being the generalist that it was, it wasn’t hard for it to recover when the Siberian Traps died down and life finally gained a foothold. It multiplied at an absurd rate and covered the earth. The early Triassic was unequivocally dominated by waddling herds of Lystrosaurus. An argument could be made that it’s the single most successful genus of synapsid in history, although MusandRattus would probably argue that point.

Whew. That was a lot. I hope it serves as a fitting return! Lystrosaurus was an animal I’d been meaning to cover for a long time, but only now felt like I was able to do it any justice. There’s so much to say about Lystrosaurus, to the point I could write a book about it. The cover would probably look something like this:

I’ll see you next time!

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Coffee, if you’d like!

Post link

Cotylorhynchus – Early Permian (279-272 Ma)

Before the Mesozoic Era, millions of years before dinosaurs even thought about showing up, was a 50 million year-long period called the Permian. You probably know that already. The Permian was the first real boom in vertebrate diversity on land. Terrestrial vertebrates had come a long way during the Carboniferous, and made several important adaptations that helped them conquer the earth during the following period. Among them was the evolution of waterproof, hard shelled, or, “amniote,’ eggs. The ability to reproduce on land let vertebrates spread all over the continent of Pangea. This is especially helpful, because the Permian was drier than the Carboniferous.

Despite popular belief, the Permian wasn’t an age of reptiles. There were big reptiles, for sure, but they weren’t the majority. The majority was the other branch of amniotes, the synapsids. They were in charge, and had free rein to turn into all sorts of weird shapes. That’s how something like Cotylorhynchushappens.

This was the biggest guy around in the early Permian, which wasn’t as big as you might think. Think a cow that’s closer to the ground, and you have Cotylorhynchus. Oh, and shrink its head a bunch, too. Do you want to know why its head was so tiny? So do I.

Yeah, its head was just kind of like that. Its body was massive for a reason, though. Well, a few reasons. Like I mentioned a minute ago, Cotylorhynchus was a built motherfucker. It was significantly bigger than anything around it, even Dimetrodon, which was only about half its size without the sail. Cow-sized was enough to be absolutely massive back then, and its sheer bulk kept it safe. It also housed a powerful digestive system to break down plant matter. It was one of nature’s first examples of the walking glacier archetype, and it even reminds me of the Pokémon Avalugg, which is a literal walking glacier. And would you believe that the best way to beat both is to not even bother challenging their defense? Just set them on fire and they’ll both go down.

But really, Cotylorhynchus was essentially indestructible in the eyes of your average early Permian predator. It’s also worth mentioning that it had a cousin called Casea, which basically looked the same but was the size of an iguana. This begs the question, which came first, the big one, or the small one? Were they all tiny with tiny heads, or did they just shrink down to that size after a while? CotylorhynchusandCasea lived at the same time, so it’s hard to say. We do know that there were members of their family who had reasonably-sized heads, on top of that.

Some other features worth mentioning: It had really broad shoulders and dexterous hands. It probably dug up roots and such as part of its diet. The shape of its skull implies it was really good at smelling, which is a good thing to be when you’re hungry all the time and constantly looking for food to nourish your colossal body. It also had long fingers and broad, paddle-like hands. Yes, I’m going there. From what we can tell about its range of motion and everything listed above, it was probably semi-aquatic. Yeah, it’s not really streamlined in any way whatsoever, but did it need to be? Manatees can get away with it. Cotylorhynchus probably swam more like a turtle, by drifting and propelling itself with its limbs. It wasn’t much more graceful underwater than it was on land, but it really didn’t have to be, if you ask me.

Post link

dimetrodon studies