#problematica

Despite the caption, these are specimens of Gluteus minimus (source)

Species:G. minimus

Etymology: Presumably named for the fossils’ resemblance to butts

Age and Location: Devonian of Iowa

Classification:Eukarya: Metazoa: ?Bilateria: incertae sedis

Thousands of these fossils, also known as “horse collars,” have been collected, and every single one of them is asymmetrical in the same direction. Because most organisms are symmetrical, fossils tend to be either symmetrical or come in mirror-image pairs, so that alone makes these strange. Some invertebrates, especially mollusks, areasymmetrical, however, though even in asymmetrical mollusks different individuals are mirror images of one another.

These fossils are solid, with internal structure, so this is not the external appearance of some bivalve or brachiopod. In fact, no animal hard part ever found bears a plausibly close resemblance to these fossils. One surface has growth lines, which provides the only clear evidence of any sort of biology for whatever organism produced these. Of all the various unlikely options, perhaps the most plausible is that it is an extremely unusual gastropod shell of some kind, but the microstructure of the shell is nothing like that of a mollusk, so these remain a total mystery.

Sources:

Davis RA., Semken HA. 1975. Fossils of uncertain affinity from the Upper Devonian of Iowa. Science 187:251–254.

Species: P. abyssalis

Etymology: “Comb of leafy branches,” after its shape

Age and Location: Ediacaran of Newfoundland

Classification:?Eukarya:incertae sedis: Rangeomorpha

Pectinifronsis a rangeomorph, and so broadly similar to Fractofusus,which also was a sessile organism that reclined on the surface, and with which it shared a presumed osmotrophic lifestyle and fractal anatomy. However, despite the simplicity of their body plans, there was still substantial variation between different genera. Pectinifronswas an enormous organism by Ediacaran standards, with the largest individuals being nearly a meter long. Unlike Fractofusus,which lay flat on the seafloor, Pectininfronswas taco-shaped, with its midline lying on the seafloor and two rows of fronds sticking upward. While superficially it resembled a folded Fractofusus, though, it appears to have grown differently: all Fractofusushave the same number of fronds and are essentially identical except for size, while larger Pectinifronshave more fronds. This suggests that Fractofususdeveloped an adult morphology early in life and simply grew by expanding itself, whereas Pectinifronsgrew by lengthening the midline of its body and growing additional fronds. Such a dramatic difference in growth strategies suggests that the rangeomorphs might be more diverse than previously thought. What kind of organism rangeomorphs are–or if they’re a single kind of organism at all–remains unknown.

Sources

Bamforth EL., Narbonne GM., Anderson MM., Bamforth EL., Narbonne GUYM., Anderson MM., Crescent S. 2008. Growth and Ecology of a Multi-Branched Ediacaran Rangeomorph from the Mistaken Point. Journal of Paleontology 82:763–777.

Hoyal Cuthill JF., Conway Morris S. 2014. Fractal branching organizations of Ediacaran rangeomorph fronds reveal a lost Proterozoic body plan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Species:E. plateauensis

Age and Location: Ediacaran of Namibia

Classification:?Eukaryaincertae sedis: Erniettomorpha

Ernietta is an iconic Ediacaran organism, and like most such organisms, its phylogenetic affinities are totally unknown, although like many other Ediacaran organisms, it may well be a stem-group animal. All we know for sure was that it was multicellular, but not apparently similar to any living multicellular organisms. A trait that defines the ‘erniettomorph’ body plan is a body The body of Erniettawas composed of essentially undifferentiated tubes of tough organic material. It appears to have lived mostly buried in the sand, with two fan-like fronds projecting into the water. Members of the genus seem to have lived together in large groups, perhaps as a consequence of their mode of reproduction.

Unlike all extant macroscopic organisms and like many other Ediacaran organisms, Erniettaprobably were osmotrophic–that is, they fed exclusively by passively absorbing nutrients from the water around them. This was possible as a result of its being essentially a sediment-filled bag, so that most of its body volume was actually just sand. The tubes that comprised the fan-like structures probably primarily served in osmotrophy while the others were structural and served to anchor the organism, however, there is no clear morphological distinction between different body regions.

Sources:

Ivantsov AY., Narbonne GM., Trusler PW., Greentree C., Vickers-Rich P. 2015. Elucidating Ernietta: new insights from exceptional specimens in the Ediacaran of Namibia. Lethaia.

Laflamme M., Xiao S., Kowalewski M. 2009. Osmotrophy in modular Ediacara organisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106.

Species:Y. magnificissimi

Etymology: “Yu Yuan animal,” after an old name for the region where the type specimen was found

Age and Location: Early Cambrian of China

Classification:Eukarya: Opisthokonta: Metazoa: Eumetazoa: Bilateria: ?Deuterostomia: ?Vetulicolia

Yuyuanozoonis a large vetulicolian, with all the taxonomic confusion that that taxonomic assignment implies. The only known specimen is from an individual 20 cm long. It consisted of a large, fusiform anterior region and a relatively short and simple segmented ‘tail’. Like all vetulicolians, it was blind and lacked any obvious external structures aside from gill slits, segmentation, and a mouth. As it had only a small, fairly cylindrical tail and lacked keels that might serve to have stabilized it, Yuyuanozoonwas probably a poor swimmer. Like all vetulicolians, Yuyuanozoonexhibited a variety of confusing traits. Besides the arthropod-like segmented cuticle, Yuyuanozoonappears to have an atrium, an internal cavity that surrounds the pharynx in tunicates. This trait makes Yuyuanzoonone of the most convincingly deuterostome-like, or even tunicate-like, vetulicolians.

Species:K. kujani

Etymology: “Kakuru,” a rainbow serpent deity in Australian Aboriginal mythology

Age and Location: mid-Cretaceous of Australia

Classification:Eukarya: Opisthokonta: Metazoa: Eumetazoa: Bilateria: Deuterostomia: Chordata: Olfactores: Vertebrata: Gnathostomata: Eugnathostomata: Euteleostomi: Tetrapoda: Amniota: Sauropsida: Sauria: Archosauromorpha: Archosauria: Avemetatarsalia: Ornithodira: Dinosauromorpha: Dinosauriformes: Dinosauria: Saurischia: Eusaurischia: Theropoda: Neotheropoda: Averostra: ?Tetanurae: ?Orionides

Kakuruis not as notable for the quality of its fossil as it is for how the fossil is preserved: the type specimen, a tibia, is made of opal. Kakuruwas a gracile, small theropod of some kind and one of the only such dinosaurs known from Australia. It’s possible that Kakuruis the only known Gondwanan oviraptorosaur.

Sources:

Barrett PM., Kear BP., Benson RBJ. 2010. Opalized archosaur remains from the Bulldog Shale (Aptian: Lower Cretaceous) of South Australia. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology 34:293–301.

P. transversa from Conway Morris and Grazhdankin 2006

Species:P. salicifolia (type),P. transversa (referred)

Etymology:

Age and Location: Devonian of New York

Classification:incertae sedis

We have no idea what this one is. It’s some kind of bilaterally symmetric, frond-like, segmented…thing. It seems to have been leathery and sac-like. Beyond that, it’s a total mystery. It doesn’t have an obvious back, front, top, or bottom. Between its totally enigmatic nature and its preservation as a sandstone impression, it resembles an Ediacaran fossil, despite being a quarter billion years more recent. While similarities have been proposed to polychaete worms, the arm of a starfish, a fish’s egg case, arthropods, and other things, no explanation seems to be satisfactory.

Sources:

Conway Morris S., Grazhdankin D. 2005. Enigmatic worm-like organisms from the Upper Devonian of New York: An apparent example of Ediacaran-like preservation. Palaeontology 48:395–410.

Morris S., Grazhdankin D. 2006. A post-script to the enigmatic Protonympha (Devonian; New York): Is it an arm of the echinoderms? Palaeontology 49:1335–1338.

Species:S. clavula

Etymology: “Little Skeem,” after the Skeem family who found the type specimen

Age and Location: Middle Cambrian of Utah

Classification:Eukarya: Opisthokonta: Metazoa: Eumetazoa: Bilateria: incertae sedis

Ah, the Cambrian explosion. We’ll be spending a lot of time here. Like Pikaia,which I wrote about yesterday,Skeemellais a debated bilaterian that may be close to the ancestry of chordates. It’s a possible member of the enigmatic Vetulicolia, a clade of exoskeleton-bearing animals that consist of a boxy anterior region and a segmented tail, which might be deuterostomes, and specifically seem to be stem-group tunicates. Vetulicolians, including Skeemella, were blind and probably poor swimmers that kept close to the seafloor. Skeemella, however, has a strikingly longer “tail” than any other vetulicolian, and it apparently lacks gill slits, which are otherwise prominent in many vetulicolians. Furthermore, it has a telson and a clearly segmented anterior body. By and large Skeemellaseems more arthropod-like than any other vetulicolian, though it’s totally unclear what kind of arthropod it could be. Vetulicolians, Skeemellain particular, also resemble the microscopic mud dragons (Kinorhyncha), a group somewhat related to arthropods, within the clade Ecdysozoa. At 14 cm long, Skeemellawas large for a Cambrian animal.

IsSkeemellaa vetulicolian? It’s hard to tell, given that only one specimen is known. It certainly resembles ecdysozoans more than other vetulicolians do, which raises the possibility that it’s an ecdysozoan that converged on vetulicolians. Alternatively, it could be a vetulicolian that converged on ecdysozoans, or it could be convergent on both, or it could be proof that vetulicolians were specialized, deuterostome-like ecdysozoans.

Sources:

Aldridge RJ., Hou X-G., Siveter DJ., Siveter DJ., Gabbott SE. 2007. the Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships of Vetulicolians. Palaeontology 50:131–168.

Briggs DEG., Lieberman BS., Halgedahl SL., Jarrard RD. 2005. A new metazoan from the middle Cambrian of Utah and the nature of the Vetulicolia. Palaeontology 48:681–686.

García-Bellido DC., Lee MSY., Edgecombe GD., Jago JB., Gehling JG., Paterson JR. 2014. A new vetulicolian from Australia and its bearing on the chordate affinities of an enigmatic Cambrian group. BMC evolutionary biology 14:214.

Lieberman BS. 2008. The Cambrian radiation of bilaterians: Evolutionary origins and palaeontological emergence; earth history change and biotic factors. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 258:180–188.

Shu D-G., Conway Morris S., Zhang Z-F., Han J. 2010. The earliest history of the deuterostomes: the importance of the Chengjiang Fossil-Lagerstatte. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277:165–174.

Reconstruction by Marianne Collins, from Conway Morris and Caron 2012

Species:P. gracilens

Etymology: Derived from Pika Peak, a mountain near the type locality

Age and Location: Middle Cambrian of British Columbia

Classification:Metazoa: Eumetazoa: Bilateria: ?Deuterostomia: ?Chordata

Pikaia,despite its fame as the lancelet-like primitive chordate of the Burgess Shale and over a hundred known specimens, is a bizarre and poorly known creature. Due to the difficulty of interpreting its anatomy, it isn’t even clear if it’s a chordate at all; the only certain feature it shares with chordates is the presence of segmented muscle blocks known as myomeres. However, myomeres are also known in the seemingly non-chordate Myoscolex,which may be an annelid. Pikaiahas only a hint of a possible notochord, but it is impossible to tell from fossils if this structure is a notochord, blood vessel, nerve, or something else.

Pikaiawas a strange marine animal, known only from the Burgess Shale, where it was uncommon but not especially rare. Adult Pikaiawere on average around 4 cm long, with the largest individuals approaching 6 cm. Like most swimming chordates, it was laterally compressed; it swam by undulating its body like an eel. However, its muscles were relatively simple and Pikaiawas probably a poor swimmer that kept close to the seafloor.

Pikaiahad a pair of small sensory tentacles in front of its mouth that served as its primary sense organs. It was probably a selective feeder; its small mouth and limited ability to expel water through its tiny pharyngeal slits would have precluded suspension feeding, which is otherwise the norm in early deuterostomes. Next to its pharyngeal slits, it had tiny appendages that may have served as gills.

Pikaiahad several bizarre internal organs of unknown function; the most prominent of these was a thick “dorsal organ” running the length of its body. This structure, once incorrectly interpreted as a notochord, may have been internal cuticle that served to stiffen the body. Because of this and other oddities, it is unclear in what ways Pikaiamay relate to other chordates. It may be a perfect example of a transitional form between primitive deuterostomes and chordates, or it may be a strange side branch of chordate evolution–if it’s even a chordate at all.

Sources:

Conway Morris S., Caron JB. 2012. Pikaia gracilens Walcott, a stem-group chordate from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia. Biological Reviews 87:480–512.

Dzik J. 2004. Anatomy and relationships of the Early Cambrian worm Myoscolex. Zoologica Scripta 33:57–69.

Lacalli T. 2012. The Middle Cambrian fossil Pikaia and the evolution of chordate swimming. EvoDevo 3:12.

Mallatt J., Holland N. 2013. Pikaia gracilens Walcott: Stem Chordate, or Already Specialized in the Cambrian. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 320:247–271.

Species:L. yini

Etymology: “Lukou Reptile,” after the Lukou Bridge (now transliterated as Lugou), in memory of the battle fought there that began the second Sino-Japanese War.

Age and Location: Early Jurassic of China

Classification:Eukarya: Metazoa: Bilateria: Deuterostomia: Chordata: Vertebrata: Eugnathostomata: Euteleostomi: Tetrapoda: Amniota: Sauropsida: Sauria: Archosauromorpha: Archosauria: incertae sedis

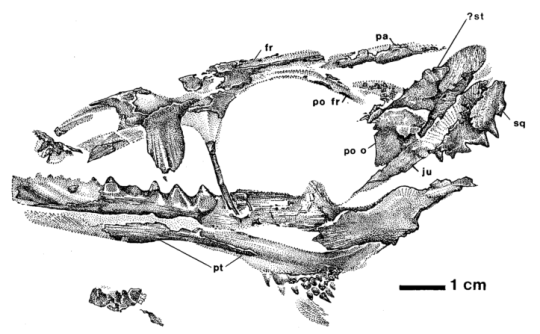

Lukousaurus,previously featured on@a-dinosaur-a-day, was first classified as a coelurosaur, back in the days that “coelurosaur” meant no more than “small or medium-sized bipedal archosaur,” based largely on the fact that its skull looked similar to a skull, SMNS 12352, assigned to Procompsognathus. However, since then, SMNS 12352 has been re-assigned to Crocodylomorpha, which makes it possible that Lukousaurus, too, was a basal “sphenosuchian”-like pseudosuchian. However, without a proper re-study of this fossil, it will be hard to know whether or not it can be assigned to that group, though that now seems more likely than is a dinosaurian identity. Whatever it turns out to be, Lukousauruswas definitely a small, predatory archosaur.

Sources:

Knoll F., Rohrberg K. 2012. CT scanning, rapid prototyping and re-examination of a partial skull of a basal crocodylomorph from the Late Triassic of Germany. Swiss Journal of Geosciences 105:109–115.

Young C-C. 1948. On two new saurischians from Lufeng, Yunnan. Bulletin of the Geological Society of China 28:75–90.

A somewhat speculative reconstruction from Dzik 2004

Species:M. ateles

Etymology: “Muscle worm,” after the preservation of its muscles

Age and Location: Cambrian of Australia

Classification:Eukarya: Opisthokonta: Metazoa: Eumetazoa: Bilateria: incertae sedis

This poorly-known organism is likely to be an early relative of the annelid worms, but little is known about its anatomy or affinities; it may be an Opabinia-like arthropod relative instead. Myoscolex was probably a free-swimming animal, however, and it was clearly abundant in the early Cambrian Emu Bay fauna. It had a laterally compressed body, and so superficially resembled early chordates in shape and perhaps lifestyle. It could grow up to 10 cm long, and it seems that as it grew it gained more segments or annulations. The body was lined with bristles, like living polychaetes. It had a clearly differentiated head, however, due to poor preservation we don’t know what the head looked like. It may have had rows of some kind of glands along its sides.

Sources:

Briggs DEG., Nedin C. 1997. The taphonomy and affinities of the problematic fossil Myoscolex from the Lower Cambrian Emu Bay Shale of South Australia. Journal of Paleontology 71:22–32.

Dzik J. 2004. Anatomy and relationships of the Early Cambrian worm Myoscolex. Zoologica Scripta 33:57–69.

Species:L. anomala

Meaning: “La Bocana,” after the place of its discovery.

Age and Location: Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Mexico

Classification:Metazoa: Eumetazoa: Bilateria: Nephrozoa: Deuterostomia: Chordata: Olfactores: Vertebrata: Eugnathostomata: Euteleostomi: Tetrapoda: Amniota: Sauria: Archosauromorpha: Archelosauria: Archosauriformes: Archosauria: Avemetatarsalia: Ornithodira: Dinosauromorpha: Dinosauriformes: Dinosauria: Saurischia: Eusaurischia: Theropoda: Neotheropoda: Averostra: incertae sedis

After the alarmingly vague Eurytholia, I thought we could return to some more familiar territory today. Labocaniais a large theropod of unknown phylogenetic position, remarkable for the robustness of its skull. It may be a member of Abelisauridae, Tyrannosauroidea, or even Carcharodontosauria, which would make it among the latest members of the latter clade. It was probably a moderately large carnivorous dinosaur, with a robustly built, possibly somewhat ornamented, head.

Sources:

Molnar RE. 1974. A distinctive theropod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Baja California (Mexico). Journal of Paleontology 48:1009–1017.

Species:K. colberti

Etymology: “Cupped hand tooth,” after the shape of the tooth

Age and Location: Late Triassic (Norian) of Arizona

Classification:Vertebrata: Eugnathostomata: Teleostomi: Euteleostomi: Sarcopterygii: Tetrapoda:?Amniota: incertae sedis

Another bizarre tooth taxon from Triassic North America, Kraterokheirodonis among the most enigmatic members of the Chinle fauna. Once interpreted as a cynodont, and in fact featured in Walking with Dinosaurs as such, it is now considered an indeterminate amniote because its only known specimens are so hard to interpret. Whatever this animal was, however, it was large–the teeth are a few centimeters across.

Each tooth seems to consist of a row of six cups of variable size lined up perpendicular to the jaw. No known animal has a tooth that looks very much like this, though the tooth root makes it likely to belong to an amniote. It looks most like the tooth of a traversodont cynodont, somewhat similar to Exaeretodon. However, closer examination suggests that these similarities are superficial at best, so the mystery remains unsolved. If it is not a traversodont, it might be a different type of cynodont, or an unusual reptile perhaps similar to Trilophosaurus. This animal will probably remain a mystery until a lucky fossil collector finds a jawbone that contains some of these distinctive teeth.

Sources:

Irmis RB., Parker WG. 2005. Unusual tetrapod teeth from the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation, Arizona, USA. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 42:1339–1345.

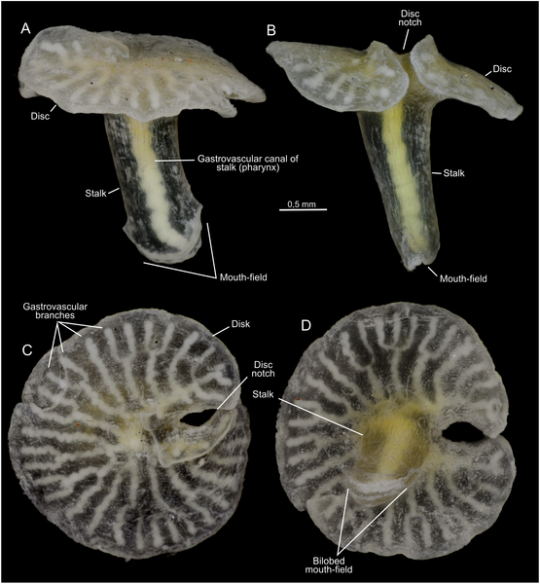

Species:D. enigmatica (type), D. discoides (referred)

Etymology: “Dendrogram,” for the dendogram-like internal structure

Age and Location: Modern ocean southeast of Australia

Classification: Metazoa incertae sedis

Dendrogrammais relatively unique among problematic life, in that it’s still alive today. Its phylogenetic position may be resolved based on DNA if any is ever successfully extracted. It appears to be a primitive animal, similar to cnidarians and ctenophores, but it is clearly distinct from both of those groups. It is possible that it may represent a new “phylum” entirely, or that it might be the only living descendant of some group of the bizzare Ediacaran biota. However, the only known specimens are juveniles, which raises the possibility that these are simply bizarre flatworm larvae, rather than a totally new branch of the tree of life.

Sources:

Just J, Kristensen RM, Olesen J (2014) Dendrogramma, New Genus, with Two New Non-Bilaterian Species from the Marine Bathyal of Southeastern Australia (Animalia, Metazoa incertae sedis) – with Similarities to Some Medusoids from the Precambrian Ediacara. PLoS ONE 9(9): e102976. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102976

Species:W. problematicus

Etymology:“Wapiti Lake reptile,” after a lake near the fossil site where it was discovered.

Age and Location: Early Triassic of North America

Classification:Vertebrata: Gnathostomata: Eugnathostomata: Teleostomi: Euteleostomi incertae sedis

This poorly-known species, known from only part of a skull, may be a large, flightless relative of the gliding reptile Coelurosauravus,and if so, would indicate that weigeltisaurs survived the Permo-Triassic Extinction. However, because of its incomplete preservation, it’s hard to prove that it’s a weigeltisaurid, so it’s largely ignored. Supposedly, it might just be a poorly-preserved fish.

Sources:

Brinkman DB. 1988. A weigeltisaurid reptile from the Lower Triassic of British Columbia. Palaeontology31:951–955.

Bulanov V V., Sennikov a. G. 2010. New data on the morphology of Permian gliding weigeltisaurid reptiles of Eastern Europe. Paleontological Journal44:682–694.

Species:U. kroehleri(type),U. schneideri(referred)

Etymology: “Uatchit tooth,” after an Egyptian cobra goddess.

Age and Location: Late Triassic of North America

Classification: Vertebrata: Gnathostomata: Euteleostomi: Tetrapoda: Amniota: Sauropsida: Sauria: ?Archosauromorpha: ?Archosauriformes

Uatchitodonis the only known venomous archosauriform. Both species have deep grooves along each side of each tooth, which were closed into tubes in the later, more specialized species U. schneideri. Other than this, however, their teeth look very much like normal carnivorous archosauriform teeth. Uatchitodonis the oldest known venomous reptile, and unlike the only distantly related modern snakes, which have a single venom canal in each fang, Uatchitodonhad serrated teeth with two canals in every tooth. Uatchitodonwas relatively widespread, as fossils have been found in Virginia, North Carolina, and Arizona.

Unfortunately,Uatchitodonis only known from these bizarre teeth, so we know nothing about what the animal as a whole looked like, other than that it was likely reptilian.

Sources:

Mitchell JS., Heckert AB., Sues H-D. 2010. Grooves to tubes: evolution of the venom delivery system in a Late Triassic “reptile”. Die Naturwissenschaften97:1117–21.

Sues H-D. 1991. Venom-conducting teeth in a Triassic reptile. Nature351:141–143.