#ride review

I rolled on the throttle. I rocked backward. The rear shock compressed. And the front wheel lifted off the tarmac.

I’m a minimalist. I own seven pairs of underwear. I own 3 pairs of shoes - black boots, brown boots, and running shoes. I own one motorcycle. And most importantly, I don’town a car.

In my quest to downsize my possessions, I asked myself:

Do I really need a shelf full of books? Not when I can borrow them from the library.

Do I really have to collect vinyls? Not when I can Spotify the record.

Do I really need a second motorcycle? Maybe we should talk about this one…

When you undertake this lifestyle, you realize that simplicity doesn’t always lend itself to functionality. You learn that you better do laundry every week or you’re going commando on Monday. You learn to dress up your boots for the work week and dress them down for weekend hikes. And you learn that you’re shit out of luck when your motorcycle gets a flat.

If that last example seems oddly specific, that’s because I recently picked up a nail in my rear tire and had to take a sick day. I rely on one vehicle to get me to and from work, so I don’t have a plan B if anything goes wrong. They say the best ability is availability and I can’t expect the Harley to be 100% one-hundred percent of the time. So maybe a second motorcycle wouldn’t be such a bad idea, right?

I know what you’re saying, “why not just buy a car?” But I’m sorry faithful reader, that sounds far too practical and honestly isn’t an option for me. I enjoy not owning a car and I will do my best to keep it that way.

With that established, I should note that I want my second motorcycle to be off-road capable? I want to take on challenging, new terrain. I want to slide the back wheel out. I want to hit the whoops. I want to ride where I won’t get obliterated by a 2-ton cage on four wheels.

With that in mind, my search invariably led me to dual sports. Though I’d prefer a dedicated dirt bike, I’d also prefer to NOT own a pickup truck. How else would I get to the trails if I didn’t own an expensive toy (in the form of a truck) to cart my other expensive toy (in the form of a dirt bike) there? How could I keep my possessions to a minimum while justifying the purchase as a “necessary, and specialized” tool (wink, wink)?

Cue Zero’s light, dual sport, electric motorcycle, the FX.

At 289 lbs, the FX touts an astounding 46 horsepower and 78 ft-lb of torque! Versus Honda and Husqvarna’s 450cc dual sports, that’s a powerful package that was just begging to be ridden. So when I swung a leg over the FX, it’s safe to say that I was giddy as an alcoholic at an open bar.

At just under 35″, the Zero’s seat height isn’t for the vertically challenged. With 8.6″ of travel up front and 8.9″ in the rear, I had to use all of my 5′10″ frame to fit the bike. While stationary, I stabilized the bike on the tips of my toes, but anyone sub-5′8″ would probably need to favor one foot at stop lights, using their leg as a human kickstand of sorts. Compared to the low slung seat of my Harley and the intermediate height of the Naked bikes I’ve ridden recently, the FX felt like straddling a donkey without stirrups.

With my toes brushing the concrete, I couldn’t help but bounce on the rear suspension. Surprisingly, the monoshock compressed quite easily, filling me with hope for undulating terrain, yet filling me with dread for twisting roads. It’s safe to say that my past experience with Yamaha’s FZ-07 left me with a residual distrust of mushy springs.

Once the rest of the group mounted up, we set out for the Hollywood Hills. Zipping along Fairfax Ave, our e-motors buzzed like a pack of RC cars, the audible whir increasing along with our speed. If there’s anything consistent across the Zero models that I’ve tested (FX & SR/F), it’s the sophistication of the throttle mapping. Without the modulation of a clutch, you would assume that the power would engage the back wheel instantaneously, but the gradual roll on aids the most ham-fisted riders and ramps up with exponential velocity as you twist your wrist.

While the FX gains speed without effort, it also holds low speeds with nuance and finesse. Squeaking past Hollywood traffic isn’t an easy feat for many a bike, but Zero’s dual sport pulls it off with a controlled low-speed mapping and steering.

The narrow frame squeezes through the smallest of spaces and its height allows the handlebars to easily float over side view mirrors. With a combination of weasel-like maneuverability and a range of 91 miles per charge, the FX challenges all other commuter candidates in the field.

As my group turned off Hollywood, leaving the urban landscape behind, I was pleased to see an empty street winding up a steep hill. That’s when the pace quickened. That’s when motor really stretched its legs. That’s when I could test out that suspect suspension.

We accelerated up the increasing incline, each rider inclined to increase the space between them and those following. We banked right. We banked left. And to my surprise, the “mushy” monoshock retained its rigidity in the corners, responding to my every input.

On my Harley, I depend on the weight of the bike to slow down my approach into an uphill corner, but on this featherweight, you barely lose any velocity. Despite my approaching speed, the bike easily negotiated each turn, relying on the combination of snappy handling and ride height/lean angle.

Though blasting through the corners is fun, speed is nothing without brakes, and the FX delivers in that department. Once we slowed to a stop, I peered down at the front rotor, floored by the fact that it only housed a single 240 mm rotor and a 4-piston caliper. The stiff, even braking left me perplexed. How could such a minimal package provide maximum performance?

I could chalk it up to the light weight of the FX, but that would be an oversimplification because the J-Juan calipers that come equipped on all Zeros have only outperformed my expectations on the bikes I’ve tested.

Once the pack regrouped at a stop sign, we turned down a side street.

I rolled on the throttle. I rocked backward. The rear shock compressed. And the front wheel lifted off the tarmac.

Now, I can’t lie, I wanted to see if I could wheelie the FX. Lacking a clutch, Zero’s dual sport has to rely on horsepower alone to get that front wheel up, and I’d be lying if I said that I wasn’t curious if it could do it. But once I achieved my goal, I came to my senses and kept my lead wrist in check.

We soon descended the domestic labyrinth, bending the fleet of Zeros through the gentle curves of the Hollywood Hills neighborhood. Little did I know, a stop sign was waiting for me at the bottom of the hill.

I stabbed the front brake. I slammed on the rear pedal. I braced for the endo. I waited for the rear to break loose. But instead, the bike eased to a steady stop, the calipers progressively clamping down on the frisbee-sized rotors.

After that close call, I diagnosed the only shortfall with the FX, and it wasn’t the brakes, it wasn’t the handling, and it damn sure wasn’t the power. The sole complaint I had for the FX was the ergonomics.

While the bars are wide, while the riding posture is upright, the height of the footpegs leave your lower quarters cramped. At a level angle, the pegs force your feet into an acute angle with your shins. Having my knees bunched up, I found myself frequently dangling my right foot where it naturally wanted to rest, under the brake pedal. Not the safest of positions when you need to brake in an emergency.

But aside from the performance of the bike, you also have to take pragmatism into account. The biggest barriers for the FX - and most electric motorcycles - are price and range. With an MSRP over $10K, I’m not sure if I could justify purchasing a bike that only nets an hour and a half of ride time. I wouldn’t be able to undertake a long trip on the FX. I would be limited to a 45-mile riding radius or risk the possibility of not making it back home. Living in the city, I’m not sure if I could even make it to the dirt with that capacity (or lack thereof).

In order to get the most out of the FX, I would need to transport it to the nearest trail, and it doesn’t make much sense to pay for a $10K bike that would need a $20K truck for me to properly enjoy it. At a scant 91 miles per 9.7-hour charge, I realized that the best ability truly is availability. And I’ll take a Harley that’s 100% ninety percent of the time versus a Zero that is only 100% fifty percent of the time.

In time, the range of e-bikes will increase and the price will decrease, but for now, I’ll rely on my good ole Low Rider…and maybe take a few more sick days.

Did you say 140 ft-lb of torque? This is gonna be fun…

My left hand extended for the clutch, but it came up empty. My left foot tapped down, but the shifter peg wasn’t there. As I rolled to a stop on Fairfax Blvd, I realized that I didn’t need to downshift. I didn’t need to rev-match. Hell, I didn’t even have to click into neutral once I was settled. What the hell was I on?

From the moment I rolled Zero’s new SR/F off the dealer’s lot, it felt like a foreign experience. Where was the grumble and burble of a combustion motor? Where was my trusty clutch lever? Where was the engine heat?

For me, motorcycles are synonymous with manual transmissions. The clutch modulates the power to the back wheel. The upshifts jolt the bike as you kick into the next gear. But with an electric motorcycle, the drive train is closer to that of a scooter, twist n’ go, and it wasn’t easy to get past that association. That is, until I hit 85 mph with the turn of the wrist!

With the lack of a transmission, the SR/F preserves as much power as possible and sends it directly to the 17″ rear wheel. Eliminating the transmission leaves us with just the engine. Can I actually call it an engine? Ok, powerplant, let’s go with that. The powerplant in the SR/F easily steals the spotlight on this bike. For touting 140 ft-lb of torque and 111 horsepower, it sure delivers all that power in a manageable fashion. I really wish I could see a dyno sheet for the bike (how would that be possible without RPM readings?), because I think it would contain the smoothest power curves known to man.

From takeoff, the torque feels like it’s closer to 70 ft-lb. It isn’t jarring. It rolls on in a controlled manner. It’s as if you were releasing the clutch slowing, though there isn’t one. But as you continue to crank the throttle, the torque ramps up and send you ripping through time and space like a fighter jet (it sorta sounds like a jet too).

Unlike Cruisers, where the torque starts out around 100 ft-lb and diminishes, or Supersports, where it tapers off while the horsepower continues to climb, the SR/F feels like the torque and horsepower escalate inseparably. It provides one of the smoothest, linear powerbands I’ve ever experienced on a motorcycle and is certainly encouraging for anyone looking to “go electric” in the future.

While I only rode on surface streets, and didn’t get a chance to toss her about in the twisties, the suspension held up like a champ. Los Angeles public roads are notorious for uneven pavement, potholes, and debris, but the suspension handled all the irregularities with ease. For me, suspension is best when it goes unnoticed and that’s exactly how I felt with the SR/F’s springs.

With fully-adjustable 43 mm Showa forks up front and a piggyback reservoir monoshock out back, the suspension is confidence inspiring and very accommodating. The ride comfort is high. The road chatter is low. The handling is predictable and snappy. Unlike the FZ-07 I rented in April, the SR/F doesn’t skimp in this category. That quality exhibits not only the capability of the bike but makes the rider want to exhibit their capabilities on the bike.

Speaking of the FZ-07, the riding posture of the SR/F is similarly neutral, if not slightly aggressive, but the attention to detail and aesthetic of Zero’s new naked truly set it apart from anything in this cluttered category and from everything else they’ve produced to this point.

The trellis frame, the futuristic front light, the tasteful mix of angles and curves all contribute the aggressive look and ultimately coalesce in a visually appealing motorcycle. For Zero, the design of the SR/F is a big leap from their past offerings. I’d compare their other models to Tesla’s lineup in the sense that they opt for a minimalistic aesthetic. When it comes to simple designs, there’s a very thin line between looking refined and looking generic. Historically, Zero’s models were on the wrong side of that fence, but the SR/F is changing that for the company. The fit and finish should be considered “premium”, and that level of quality is reflected in all the separate components of the bike, including the brakes.

With radial-mounted clampers on 320 mm dual discs, the SR/F practically stops on command. The J.Juan branded calipers pack a suitable amount of stopping power, considering they’re stopping a 500 lb bike and they aren’t emblazoned with the Brembo badge. The feel was responsive yet smooth, stiff but progressive.

Out back, you have a single 240 mm rotor and a 2-pot caliper. Compared to the robust braking components up front, the rear would seem considerably underpowered, but it does an above average job of slowing down the bike (albeit, my “average” standards are quite low, as I ride a Harley). Coupled with Bosch Advanced MSC (a fancy acronym for traction/stability control), the braking system of the SR/F upheld the premium status of the bike. Sure it doesn’t offer the name recognition of Beringer or Brembo, but they get the job done. And isn’t that what brakes should be about, getting the job done?

Now, I know what you’re probably saying:

Yeah, that’s all great and all, but would you buy one yourself?

And the short answer is no, but let me explain. The SR/F is a revolutionary machine. In my humble opinion, it marks a sea change for the electric motorcycle market and ups the ante for competitors like Lighting, and dare I say, Harley-Davidson.

But the infrastructure hasn’t caught up with the product yet. I can’t confidently say that I would (or could) go on a Pan-American trip with this or any electric motorcycle yet and that’s disheartening because I know that will act as a barrier for potential customers.

As the technology progresses and charge stations are erected, I know the viability of these machines will increase. They won’t just be considered a commuter bike. You won’t have to stay within a certain distance from home when you go for a rip about town or through the twisties. But right now, I don’t have the disposable income to spend $20K+ on a motorcycle that would need to stay regional.

Electric vehicles (cars & bikes) are the future. Whether you’re happy, excited, or ready for that change is beside the point. I fully intend to be an adopter but we’re currently in a stop gap of that transition and I need the baton to be firmly in the grasp of EVs before I make the jump (I’m never selling the Harley though). To me, it’s inevitable, but only time will tell when the takeover takes place.

However, if you have the money to purchase an SR/F, do it, now! If you’re someone fortunate to own multiple bikes, this one would be a purposeful horse in your stable. At my income level, I’m relegated to bikes that are Swiss Army knives but the SR/F could easily be your X-ACTO knife.

Whether you’re opposed to electric motorcycles or a proponent of them, do yourself a favor and give one a try. It’s a motorcycle, guys, you’d be hard pressed not to have fun.

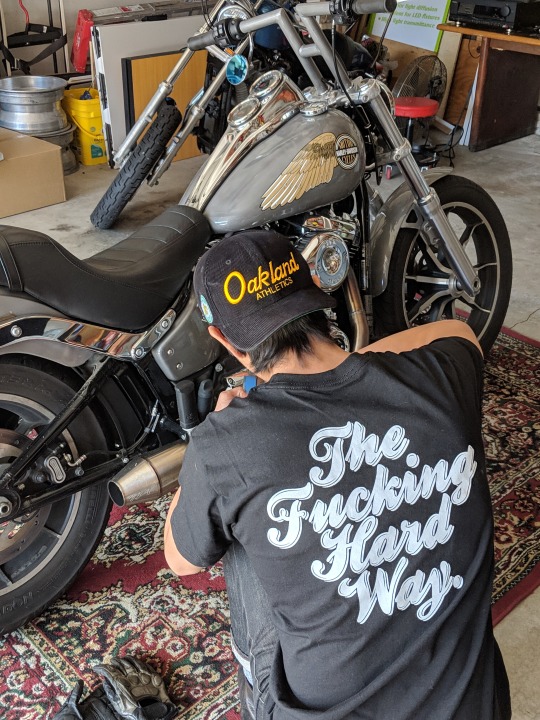

Whenever I read or watch motorcycle reviews, I can’t help but notice a heavy reliance on spec sheets. And I get it, approaching a subjective review of a product with an objective data set certainly helps set the playing field for all competing models. However, this post isn’t about the latest electric naked bike that just hit the market or the revamped scrambler that is being hyped as “game-changing”. This post is about my daily rider.

With that in mind, I could dwell on the dual-bending valve Showa forks, or my high-flow S&S air cleaner, or the 102 ft lbs of torque that the Milwaukee 8 engine produces. But bragging about your bike’s specs is like plastering a “Proud Parent of an Honor Student” on your bumper or boasting about how attractive your significant other is. They’re used to favorably reflect on you, not reflect how that person - or in this case, motorcycle - makes you feel. Sure, your girlfriend could be model material but if she treats you like shit, why does her “hotness” matter, right?

So I’m not going to take that approach in this review. Instead of flooding you with figures on compression rates, length of suspension travel, or lean angle**, I’m going to explain how all of those things contribute to the feeling she gives me.

**Please see the stock spec sheet here (if it interests you)

I purchased my Low Rider in April of 2018. I had to trade in my Sportster Iron 883 - which was heartbreaking for me at the time (see the story here) - but it was well worth the sacrifice. From the moment I rolled her off the lot, I knew I made the right decision.

She handled better than the Sporty. She accelerated WAY faster than the 883. And most importantly, she braked lightyears beyond the Iron.

Now, I know what you’re thinking:

I don’t want to know if it’s better than a Sportster, I want to know whether it’s a good purchase.

But I think it’s important for me to establish the bike I originally owned and how that shaped my assessment of the FXLR, and the first place I noticed an improvement was in the suspension.

The combination of Showa forks up front and the monoshock out back puts Harley’s past suspension offerings to shame. For 650 lbs., the bike feels responsive and surprisingly nimble. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the bike dives into corners and I’ve definitely put that feature to use. But the fork not only allows you to attack the twisties, but it also does a great job of keeping the rubber to the road. The wheel hop of the Sportster: eliminated. If you’re debating whether you should buy a new Softail, I could easily make a case with the upgraded forks alone, but that’s just the front suspension, you still have the brilliant monoshock in the rear.

While the fork provides improved handling, the rear suspension grants a new level of comfort. Those potholes no longer send shocks through my spine. Those railroad tracks no longer make my teeth click. Those road irregularities no longer buck my girlfriend off the seat. And if there’s any barometer of rear suspension performance, it’s your old lady’s ass…and mine loves the FXLR. But comfort isn’t the best feature of the monoshock, the stability it provides is. I’ve hit 120 mph twice on the Low Rider thus far, and the stability of the bike never faltered. The speed wobbles of the Dyna: eliminated. Are you noticing a theme here yet?

But don’t get me wrong, the suspension isn’t perfect. There’s no adjustability in the front and the rear doesn’t give you dampening or rebound settings. Also, you have to remove the seat to adjust the monoshock. Unless you’re planning on carrying a flathead screwdriver on you, I wouldn’t set my heart on changing the preload on the fly.

Now, I should note that I plan on upgrading to Ohlin’s suspension (front & rear) in the future, but the stock setup would be sufficient for 90% of those looking for a Harley.

Ultimately, the OEM suspension makes me feel grateful. Grateful for the safety it provides. Grateful for the responsiveness it adds to such a massive bike. Grateful that I get comfort and performance right out of the box!

Which leads me directly to the heart of the Low Rider, the Milwaukee 8 motor.

It shakes less. It runs cooler. It pulls harder (through all 6 gears). Compared to the Twin Cams I’ve ridden, the M8 outshines them in every way. To be honest, you’ll probably need to regulate your own speed if you buy a new Softail because they’re most comfortable at 85-90 mph. Every time I ride on the highway, I hit 100 mph at least once (unintended and intended). There have been many times where I unconsciously hit 70 mph on surface streets!

On the flipside, the M8 is very particular when it comes to modifications. My tuner/mechanic has told me that finding the right configuration of parts is crucial to any performance upgrades you install on the new mill. Luckily, I had some guidance, but if you’re considering customizing your Milwaukee 8, I suggest consulting a professional - or at the very least read some forum boards - before you slap on any old exhaust or fuel manager.

On the note of fuel management, if you want to maintain the maximum range (200+ miles per tank), leave the engine in stock form. After my numerous mods, I’m lucky if I can squeak out 150 miles between fill-ups. I’d be lying if I said I regret sacrificing those additional 50 miles per tank - because Sofia absolutely rips - but it’s something you should weigh before buying or upgrading an M8.

If I had to express how the engine makes me feel, I’d say it makes me feel spoiled. Spoiled by all that torque. Spoiled that she pulls through all 6 gears. Spoiled that I get the power of a Harley without all the shaking or heat.

Now, we’ve been dwelling on speed up to this point, but if you’re planning on going fast, you have to be able to stop as well…

When it comes to the brakes, I have to caveat that I ride my Low Rider harder than most Harleys are intended. I currently need new rotors, pads, lines (braided), and a master cylinder rebuild because I’ve run the brakes into the ground.

Though the front end is only outfitted with a single disc, the bite of the 4-piston calipers really help to slow down the 650 lbs. of the Low Rider. While the front brake lever loses feel over time - due to the rubber brake lines - it easily retains the forceful braking of those 4-pot calipers. However, the same can’t be said of the rear caliper, which lacks any responsiveness and is downright mushy.

Most riders say that the front brakes provide 70% of your stopping power while the rear covers the remaining 30%. On the FXLR, that ratio is more like 90/10. But in the end, you’re riding a Harley, and Harleys have never been known for their braking components. Now, that’s by no means an excuse, but if you’ve ridden a Harley before, your expectations are already set appropriately. If not, good luck!

With the vague feel of the rear pedal and the diminished responsiveness of the front lever over time, I’d say that the brakes make the bike feel sketchy. But hey, you’re riding a chopper, baby! Sketchiness is part of the package.

In the end, if I had to do it all over again, I would buy the Low Rider every time. The bike outperforms every Harley I’ve ever ridden and it’s one of the most aesthetically versatile platforms under HD. You can go Club Style, Bobber, Chopper. Hell, I’ve even seen Scrambler and Cafe Racer M8 Softails. It’s for that reason, that I didn’t cover the design of the Low Rider. I think my bike is the perfect example of the FXLR being a blank canvas for you to customize yourself.

Now the only question left is: when are you upgrading?

Size does matter, and in this case, smaller is better.

It’s no secret that Husqvarna’s dirt bikes and dual sports sell themselves. Touting a storied motocross/scramble history, it’s easy to see why the off-roaders are so popular with the public. On the other hand, the company hasn’t seen much success with its street-oriented lineup. With 2019s still occupying the showroom floor and the pressure of Q3 looming, Husky recently visited Azusa, California to jumpstart the sales of their Svartpilen & Vitpilen lines. Labeled the Real Street tour, the series of demo events featured both models in their 401 & 701 variations, casting a veritable spotlight on their often overlooked street bikes.

But the Svartpilen & Vitpilen aren’t afraid of the spotlight, you could even say they were crafted to bask in it. The first thing you’ll notice when you gaze at the Svartpilen & Vitpilen is the unconventional design. It’s not a stretch to say that the aesthetics of the lineup resemble something out of a Scandinavian furniture catalog. With minimal, flowing lines, the Svartpilen & Vitpilen would feel right at home with your Poäng and Klippan.

Yes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but the neo-retro style aims directly at a younger, urban demographic that gravitate toward classic, simplistic forms with a utilitarian edge. Whether you fancy the looks of the bikes or not, you have to admit that the fit and finish is quite impressive. However, I do feel the designers tragically overlooked the speedometer, as its more akin to a gym teacher’s stopwatch than a proper gauge. Not to mention, the highly reflective glass and mounting angle make render the information illegible. Aside from the hideous - and quite useless - instrument cluster, the Svartpilen & Vitpilen reek of smart sophistication.

But I can see how that elevated design could be a barrier for potential buyers. Due to the refined, “Swedish” aesthetics, one could quickly distinguish these models from their intra-brand cousins, KTM’s Duke and Enduro. With hopes that the public will embrace these models the same vigor as they’ve taken to KTM’s lineups, Husky is just trying to get more booties in the saddle, and I’m more than happy to oblige.

Sharing the motor of KTM’s 390 Duke and 690 Enduro R, Husky’s Svartpilen & Vitpilens benefit from two well-tested mills. Both engines push the boundaries of power that a single-cylinder engine should produce. Despite the lack of pistons to share the load, the vibrations on the 401 & 701 aren’t excessive (take that assessment with a grain of salt - I ride a Harley).

While the 701 delivers its power in a smooth, linear fashion, I found myself smitten with the 401′s punchiness. Glancing at the spec sheet, I noticed that the 701 reaches peak torque of 53 ft-lb @ 6,750 rpm with 75 hp topping out @ 8,500 rpm. Comparatively, the 401′s max torque (27 ft-lb) hits @ 6,800 rpm and horsepower (42 hp) @ 8,600 rpm. With about half the power and three-quarters of the weight of the 701, the 401 shouldn’t feel nearly as torquey. Additionally, both motors achieve max torque and horsepower at practically identical rpms, leaving me perplexed with my preference for the 401 - aside from the butt dyno.

No, I can’t support my fondness of the little thumper with cold hard data, but I can attest that the majority of the riders attending the demo agreed. I know anecdotal evidence is the least persuasive argument, but the 401 simply felt like a more agile from side-to-side and provided great acceleration in short bursts. And I may be rationalizing here, but those darting characteristics seemed appropriate for two models that translate to white arrow (Vitpilen) and black arrow (Svartpilen). The 701s weren’t bad motorcycles in the least, they just didn’t imbue the same excitement as they’re diminutive counterparts. Size does matter, and in this case, smaller is better.

But the size variation didn’t stop at the engine. The differing braking systems on the bikes occupied two different build quality standards. Even with the 401′s “budget” brakes, both systems felt well-suited for their classes with adial-mounted Brembo clampers blessing the 701s and ByBre calipers getting the job done on the 401s.

Despite the fact that both models lack dual-discs, the calipers delivered a reassuring bite while riding in urban environments. Yes, an extra rotor and caliper up front would certainly push the models in a more performance direction but we didn’t take the Svartpilen or Vitpilen into the twisties and the stock brakes would suffice where most buyers would ride these bikes - in the city.

When judging the two models on ergonomics, I kept their natural habitat - urban environments - in mind, as both maintain a fairly sporty position. Starting with the Vitpilen, I immediately noticed the aggressive, forward-leaning stance. Positioning my head directly over the front wheel, the Vitpilen made me want to slalom through mid-day traffic at full throttle. However, that state of mind prooved more enslaving than freeing. After all, I was on a demo tour. If “it’s better to ride a slow bike fast than a fast bike slow,” nothing is worse than living that platitude in reverse. If you’re looking for a nimble, aggressive, lane-splitter, the Vitpilen has you covered, but make sure your journey is manageable, as I already felt the tension in my wrists by the time we returned from the short ride.

On the other hand, the Svartpilen utilizes high-rise bars to position the rider at ease. From the upright posture, I was content to stay in line and putt along at a legally acceptable speed. Sure, I tugged on the throttle from time to time, but the relaxed stance felt more conducive to congested road conditions. If the Vitpilen’s ergonomics equate to a Supersport, the Svartpilen would be it’s Naked/Standard counterpart. Both bikes are aimed at city-dwellers and while it would be a stretch to say that either of them let you stretch your legs out, neither of them feel cramped. Though I’d probably opt for the Svartpilen in most situations, if I were visiting one of the local canyons (GMR, HWY 39, etc), I’d certainly side with the Vitpilen.

While the ergonomics shift the rider into different postures - and different states of mind - the road manners of the bikes are quite similar. With all models under 6 inches of travel, I could easily flat-foot each bike. Despite its smaller stature, the 401s benefited from the same WP 43mm inverted forks that graced the front end of the 701s. On the road, each bike was compliant and responded immediately to my every input. Particularly, the Vitpilen - with its clip-ons and head-down posture - reacted to every adjustment of my body.

Not only did the suspension allow the bikes to cut from side-to-side, it also made the 401s and 701s feel planted. From soaking up potholes to providing stable steering at speed, KTM’s proprietary suspenders highlighted how fun these machines can be. On the contrary, the lack of suspension travel on the Svartpilen did beg the question: couldn’t this model be much more fun? Aside from ergonomics and a few bits of design (paint mainly), how does the Svarpilen distinguish itself from the Vitpilen?

And that’s where I got to thinking about the lack of sales for these two models. After taking everything into consideration, it seems like Husqvarna’s “Real Street” motorcycles are going through an identity crisis. Are these bikes retro or performance? Can you consider a motorcycle “premium” (as the price would suggest) the dash looks more like a digital alarm clock and it doesn’t come with dual-disc brakes? But maybe it’s less of an identity crisis and more of a false identity. For instance, Husqvarna outfits the Svartpilen with dirt tracker styling yet they can’t endorse taking the low slung machine off-road. Even with the aesthetic hinting at dirt-capabilities, the Svartpilen is essentially a naked bike with knobbies.

Broadcasting a false image can ensnare potential buyers - or it can turn them off (like it did for me). Intoxicated by the snappy acceleration of the 401, I actually looked into purchasing a Svartpilen following the demo. But the lack of off-road capability soon soured my initial enthusiasm. If it can’t hang in the brown, why outfit it with Pirelli Scorpions? Why adopt tracker design cues? What’s the point of making form decision if it’s contrary to the function? That disillusionment made me look at the Svartpilen & Vitpilen differently.

With an MSRP of $6,299 for the 401 and $11,999 for the 701, it’s easy to see why the KTM-owned brand is having problems moving units. Coupled with the unconventional design (which I actually love but can understand how some wouldn’t), Husqvarna has it’s work cut out. Along with the lackluster sales figures of the Svartpilen & Vitpilen, the Real Street Demo stop in Azusa failed to highlight the full capabilities of models. With the near highway miles away, riders were relegated to a jaunt around the block. As a result, I never got the gearbox past 3rd and that doesn’t instill much confidence in potential customers. The combination of disorganization, bikes-to-rider ratio, wait times, and early wrap-up, I’d venture to say that the demo barely moved the needle on these two bikes.

With all that said, if you’re looking for a stylish motorcycle to ride in the city, Husky’s street lineup may be a good option. The brand continues to promote their 0% APR (up to 48 months), so you may score a new Svartpilen or Vitpilen for a great price. For my intents, the bikes are too niche in design and too specialized in purpose, but that doesn’t mean they won’t work for you. I guess the best advice I can give to potential buyers is to test ride as many motorcycles as possible. I know I will be!

Let’s just get this out of the way, I wouldn’t buy the GT 650 or INT 650 as my second bike. I’d buy it as my first.

Up to this point, I’ve been judging motorcycles based on my personal search for a second motorcycle. My criteria consisted of 4 qualities: cheap, dirt-capable, lightweight, and powerful (added after I rode the Himalayan). On that note, neither of Royal Enfield’s new Twins meets those standards. Let’s just get this out of the way, I wouldn’t buy the GT 650 or INT 650 as my second bike. I’d buy it as my first.

Due to my first experience with Royal Enfield’s Himalayan, I had low expectations for the brand’s new 650s. The underwhelming power delivery, over-anxious brakes, and inconsistent suspension of the mini-ADV left me skeptical of Royal Enfield full lineup. It’s safe to say that I reeked of a dismissive air when I swung a leg over the INT, but my generalization of the brand was quickly remedied with the first whack of the throttle.

Every motorcyclist knows the feeling of a good pull. It’s when the acceleration pushes you back in the saddle, when the rear shock compresses and the fork lightens, when you tighten your grip on the handlebars for fear of sliding off the back. My first pull on the INT 650 delivered such a sensation, so much that I said (out loud), “Whoa! That’s more like it!”

That 648 cc, single overhead cam engine that sent me hurtling through space and time happens to be the heart of the new Twins. With a torquey low-end power delivery, the engine boasts an exciting edge yet retains an affable disposition. Whether you’re running the Twins through their paces or cruising about town, the middleweight mill is happy to comply. For those hipsters looking for a CB750 or XS650, you no longer have to sacrifice reliability for aesthetics. The GT and INT 650 gives you the best of both worlds with smooth, efficient EFI fuel distribution and cafe racer styling.

In my short time with the models, engine heat never factored into the equation either. Even with that day’s temperature topping 90° F, the oil/air-cooled mule inside the Twins never skipped a beat, even when the pace hastened. Although Royal’s 650s did get up to interstate speeds without hesitation, I should note that both models feel more at home on surface streets. The torquey motor benefits the urbanite from stoplight-to-stoplight and the lack of wind protection would quickly fatigue riders on longer journeys.

Along with the punchy power delivery, the width of the frame, handlebars, and pegs allow the commuter to squeeze through the narrowest of spaces. I wish Royal’s Twins were on the market when I started riding because they’re great options for those just starting out, especially when it comes to the controls.

Like all of Royal Enfield’s lineup, the GT & INT opt for simplicity. The company tends to label its approach as “Purist” and a quick glance at the controls will drive that point home. Without the luxury of a TFT display, cruise control, or heated grips, the controls of the Twins are minimalist. That facet helps developing riders concentrate on the road instead of fiddling with menus and settings, allowing them to get comfortable with the clutch, throttle, and most importantly, the brakes.

Both models boast a single 320mm floating rotor with a two-piston ByBre caliper up front and a 240mm floating rotor clamped by a single-piston caliper out back. ByBre, the Indian subsidiary of Brembo, provides the braking components. I know what you’re thinking (Indian-made Brembos?), but the stopping power achieved with these “budget” calipers really do the job. Coupled with the 41mm fork and piggyback shocks, the braking system brings the hefty 450 lb bike to an even and controlled stop. Yes, neither component truly stands out on these bikes, when it comes to brakes and suspension, that’s usually a good thing!

It’s true that the INT & GT 650 share the same 648 SOHC engine, ByBre brakes, double-cradle steel frame, 41mm conventional forks, and coil-over rear suspension. However, they do differ in two major categories: aesthetics and ergonomics. The INT opts for a pseudo-scrambler look with high-rise handlebars (w. crossbar), bench-style seat, and mid-mount pegs. While the GT sports proper cafe racer cosmetics with clip-ons, single-seat (w. cowl), and rear sets.

Despite the ergo divergence, both the Twins handled responsively, although I wouldn’t call them lithe. The added girth of the larger engine means that the supporting package needs beefing up (compared to other Royal Enfield models). As a result, the 650s weigh more than any other Royal Enfield and the extra poundage is evident in the corners. I wouldn’t label the Twins as unwieldy, but I also couldn’t praise them as flickable.

As a cruiser rider, the upright posture of the INT felt more natural, but the GT also proved the advantages of aggressive body positioning. With my abdomen lower to the tank, wind resistance was less of a factor and the direct input of the clip-ons resulted in a more reactive quality from the front end. Though the INT responded well to all of my inputs, I could dart through traffic on the GT (even if that feeling is primarily psychological - due to the ergonomics). For that reason, I think I’d side with the GT, as I’d primarily use both of Royal Enfield’s 650 in the city - and that’s where most consumers will ride these bikes.

With a base MSRP of $5,799, the GT & INT would be a viable starter bike for commuting students and city-dwellers. While most people warn novice riders against buying a 600+ cc motorcycle out of the gate, the 42 horses and 37 ft-lb of torque make the Twins manageable for newcomers.

The retro-styling of the models will definitely appeal to a younger crowd and the affordable price point keeps them within reach. New riders tend to focus more on the aesthetics, but they will inevitably drop the bike (…a few times) and a lower price tag always helps to cushion those falls. If I were in the market for a first bike now, I would seriously reconsider buying the Harley-Davidson Sportster Iron 883, and I LOVED that bike.

If you’re new to the sport or searching for your first bike, I’d strongly suggest a test ride of the GT/INT 650. The combination of aesthetics, price point, approachable demeanor, and simplicity make Royal Enfield’s Twins a very attractive package. Not to mention, the 3-year, unlimited miles warranty with roadside assistance, reinforces the build quality of these machines. Believe me, If the company released a dirt-capable twin at a lighter curb weight, I’d be all over it. While that’s irrelevant when it comes to these models, the experience wasn’t for not.

For me, Royal Enfields Twins were cheap, they were powerful, they just didn’t have taller suspension and knobbies that I’m looking for. Though I don’t plan to purchase the GT or INT 650, I learned that I will need my second bike to be commute-capable. The narrow footprint of the controls illustrated the importance of squirting through tight spaces in an urban environment. I guess my next bike will not only have to be cheap, dirt-capable, lightweight, and powerful but also commuter-friendly. I’m sure I’ll find that package in time, but for now, it’s on to the next bike!

The tach needle bounced off the red line. The motor screeched. My hands clenched the grips. An 18-wheeler barreled by with a gust of displaced air, pushing the bike - and me - to the side of the highway.

In my quest to find the perfect second motorcycle, I’ve rented an FZ-07. I’ve test ridden Zero’s naked bike, the SR/F, and demoed their dual-sport, the FX. While all of those bikes were great in their own respects, none of them met my criteria: light, dirt-capable, and cheap. So when I heard that Royal Enfield was launching a nationwide tour featuring some of their newest models, I knew there was strong potential to find my scrambling side piece.

Titled Pick Your Play, Royal Enfield’s demo ride event brought me to the highly revered Southern California Motorcycles in Orange County, CA. If you should know anything about Royal Enfield, it’s that the Indian company relies on classic styling with no-frills engineering. You won’t find traction control or TFT displays on their motorcycles. Liquid-cooling and heated grips aren’t featured on any Royals. Shoot, most of the models don’t even have gear indicators.

It’s this unabashed appeal to the “purist” that differentiates the brand from its competitors while keeping their prices low and their “cool” factor high. However, harkening back to yesteryear not only attracts hipsters it also attracts the riders that were around for the original Cafe-styled bikes: old dudes! And if you’re looking to attract aging gentlemen, you’d be smart to host your demo rides in the bastion of affluent retirees - The OC.

Aside from the 3-4 participants that were in my age group, I’d estimate that the majority of the attendees were collecting Social Security. Let’s just say that there was an abundance of high-viz gear and modular helmets. One of my favorite guys was even sporting a shirt with the term “Air-cooled” emblazoned across the chest. Now, please don’t read any of the previous statements as ageism. I LOVE old dude shit (I mean, I ride a Harley). I only point out the age discrepancy because Royal Enfield specifically cast the spotlight on the INT 650 and GT 650 for the Pick Your Play event, two models aimed at a younger rider.

Though attendance was strong, I’m not sure if Royal Enfield expected this turn out when they pushed off on their 8-city tour. To the company, these retro-cool, city-dwelling models cater to a younger demographic. If I can’t convince you of that fact, maybe the event flyer can…

With all of that in mind, when I approached the sign-in desk to reserve my first demo ride, I did the most “old dude” thing possible, I asked to test out Royal Enfield’s adventure bike: the Himalayan.

The Himalayan was dirt-capable. Check! The Himalayan was light (well, lighter than my Harley). Check! The Himalayan was cheap. Check! So when I threw my leg over the 31.5 inch-high seat, I couldn’t help but have high hopes for Royal’s compact off-roader.

As the instructor hollered liability terms and the obligatory sales pitch, I looked over the bike. The simplistic, classic lines spoke to my minimalist preferences. The lack of gadgets and rider aids made the model feel immediately approachable.

With its metal tank, bare-bones instrument cluster, and halogen headlight, the vintage-styled dual-sport looks like it could have been a contestant in the original Dakar Rally of ‘79. Based on looks alone, it would be understandable if you confused the Himalayan for BMW’s iconic R80G/S. But Royal Enfield isn’t sharing market space with Beemer’s first GS, it’s up against a much more advanced generation.

Unlike the leader of the adventure class, BMW’s R 1250 GS, the Himalayan doesn’t boast a navigation system with Bluetooth connectivity, you won’t find a quick-shifter on it, there isn’t an Electronic Suspension Adjustment system, it doesn’t need Hill Start Control (does anybody?). But also unlike the GS, Royal’s ADV isn’t ugly as sin, and that may be the bikes biggest appeal, its aesthetics.

From the exposed sub-frame to the fork gaiters, from the skid plate to the ‘HIMALAYAN’ branded side panels, from the cafe-esque gas tank to the aluminum panniers, Royal Enfield’s thumper is easy on the eyes (as far as adventure bikes go…). The single-cylinder engine, tank guard, and high front fender complete a very tasteful package. But once I finished ogling the thing, I wondered to myself, ‘would function live up to form?’

I settled into the ultra-comfortable seat, grasped the handlebars, and retracted the kickstand. With my right boot resting on the peg, I jammed the shifter into first gear, revved the engine, and slowly released the clutch. To my surprise, the friction zone didn’t engage until I was about 3 quarters of the way out. I’m sure this was a result of tens of thousands of miles racked up on a nationwide demo tour, but it certainly brought back a long lost feeling, as memories of stalling out flashed before my eyes. I thought of the time I bogged the engined and dropped the bike in an intersection. I cringed as the sound of honking horns came rushing back. Thankfully the power kicked in just in time, relieving me of that dreaded “novice” embarrassment (especially in front of these seasoned riders).

Once I got up to speed, I repositioned my feet, a necessary adjustment on the Himalayan. With the pegs residing directly under the rider and the pedals at a level angle, I couldn’t decide whether I wanted to scoot fore or aft on the saddle. I eventually sided with a forward-leaning posture, but that left me feeling as if I was mounting a rocking horse.

Luckily, I was able to work myself into a passable position as we approached our first light. At a slow roll and with the relatively low seat height (for an ADV), I could duck walk the bike, a comforting attribute when you’re new to adventure riding, even if it makes you feel like a toddler on a pushbike. But it’s when you twist the throttle on the Himalayan that it makes you feel like you’re actually on training wheels.

Touting 25 HP and 20 ft-lb of torque, Royal Enfields little 400 felt like it was running through mud, despite the fact that we were rolling over fresh pavement. Though I didn’t record the time any of my 0-60 mph pulls on the single-cylinder scoot, the combination of the stocky frame and the anemic motor allows me to comfortably hypothesize that it was well into the double digits (in seconds).

The inherent sluggishness of the Himalayan was most evident in one of the worst places possible: the freeway onramp. As the group merged into the congested lanes of Highway 57, I cranked on the throttle. The tach needle bounced off the red line. The motor screeched. My hands clenched the grips. An 18-wheeler barreled by with a gust of displaced air, pushing the bike - and me - to the side of the highway.

Luckily our freeway run only lasted a quarter-mile, as the fleet of Royals exited at the very next turnoff. Re-entering the comfortable confines of surface streets allowed me to re-gather my wits and put the Himalayan back where it belonged, on roads with speed limits below 65 mph. At this point in the demo, I saw RE’s little adventurer as a glorified moped with taller suspension and better ergos. It didn’t help that in addition to the unenthused acceleration, the bike didn’t receive any help from the clumsy gearbox.

At only 5-gears, the transmission felt like an accurate reflection of the Himalayan’s $4,499 MSRP. I found myself unintentionally shifting into neutral several times throughout the ride. It was quite amazing that I could find neutral not only during my upshifts but also during downshifts. The problem is, I was trying to find 1st and 2nd, not neutral. On the other hand, I’m grateful that Royal Enfield outfitted the dash with a gear indicator so I could quickly identify any hiccups with the shifting. That feature was certainly handy when I rolled to a stoplight in 3rd gear, but that’s where the bike really performed - while braking.

Though the engine was more worthy of a golf cart, the brakes felt like they came off a Mack Truck. Sporting a 2-piston caliper up front and a single-pot caliper out back, the braking system of the Himalayan may have been the most impressive aspect of the mini-ADV. While the braking components don’t sound powerful on paper, in concert, they performed with a high level of efficiency and effectiveness, bringing the bike to a halt with immediacy. At times, it felt like the braking power was almost too effective, especially given the bike’s suspension.

Fork dive never results in a good feeling, but with such powerful brakes and flimsy 41mm fork legs, the sensation was inevitable on the Himalayan. Coupling two incongruent systems usually highlights the deficiencies of the pairing rather than the benefits of the exceptional component. Yes, the brakes of Royal’s ADV stood out, but the collapsable front suspension only turned that positive into a negative.

At the rear, the monoshock exhibited stiffer, more responsive reactions to braking/acceleration and road irregularities, but the inconsistency of the unit also plagued the ride. For a model that’s supposed to spend a good portion of its life in the dirt, I doubt the combination of the underpowered motor, 420lb+ curb weight, and remedial suspension would be helpful off the pavement. I wouldn’t feel comfortable tackling anything more challenging than a fire road on the Royal. That’s especially sad for a bike named the Himalayan.

On that note, I was relieved that we never rode the bike in the brown. Although you don’t need all the power in the world when you’re riding off-road (in some cases it can be a detriment), you do need to be able to get yourself out of tight spots and over obstacles, two things that seemed daunting to me while riding atop the overweight/underpowered ADV.

The sub-500cc dual-sport market is dominated by motocross-inspired machines originally designed in the ‘90s (& unchanged since) and the Himalayan is a breath of fresh air - even if its design plays on a past era. With retro styling and fuel injection, it’s ironic to say that the Royal Enfield is enlivening the segment. But with most of the models in the category approaching 3 decades of continuous production, it’s nice to see someone trying something different. Even if the dual-sport consumer focuses more on specs than looks, the Himalayan may attract an audience due to the simple fact that it is different.

For me, I don’t think the concessions made in function are worth the nominal boost in form. Weight to power ratios reign supreme in the dual-sport world and RE’s thumper resides at the losing end of both spectrums. Weighing in with the 600s and generating the power of a 250, the only saving grace for the Himalayan is its aesthetics and price.

I’m not a rider that needs (or wants) Bluetooth connectivity. I’m happy to go without traction control. However, opting for the “purist” route shouldn’t mean sacrificing the performance of the machine. There should be a mean between maximal and minimal, a median between overpriced and underperforming, a middle ground of handsome and hideous. If BMW’s R 1200 GS is the thesis of the Adventure market, the Himalayan is the antithesis, and what I’m looking for is the synthesis of those two ideas.

With that, my search for a perfect second bike will continue. What I thought was an easy feat, seems to be more elusive than I anticipated. Along with light, dirt-capable, and cheap, I’ll need to add a few other attributes to my criteria, and of course, that means I’ll have to test out more motorcycles…

Poor me ;)