#romanov dynasty

I’ve been looking forward to reading this book for several months, but I also want to point out how cool-looking it actually is. It’s kind of difficult to see in the photo, but the actual hardcover of the book has an embossed version of the book jacket graphics. Nobody makes better-looking books, aesthically, than Knopf.

The Romanovs: 1613-1918(BOOK|KINDLE) by Simon Sebag Montefiore is available on May 10th.

Post link

«The Empress with the medical staff went around the wounded, provided first aid, tried in every possible way to ease the sufferings of the sick, despite the fact that she herself had a damaged arm above the elbow and she wore just a dress. An officer’s greatcoat was thrown over the shoulders of the tsarina, in which she walked along the crashed train…»

A. Myasnikov about Empress Maria Feodorovna on the day of the tragedy at the Borki station.

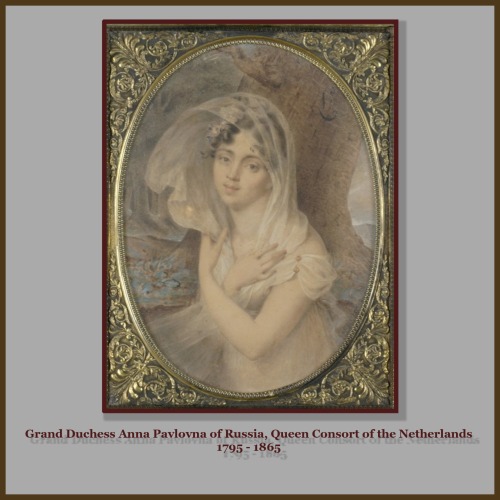

The Grand Duchesses: The daughters of Tsar Paul I: Part V: Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna (1795 - 1865)

Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna was the eighth child and sixth daughter of Emperor Paul I. She was born after Paul’s seventh child and fifth daughter, Grand Duchess Olga Pavlovna; Olga did not live past her third year.

Anna received a good education. Because she was raised with her brothers, Michael and Nicholas, to whom she was closest in age (she would remain close to the future Nicholas I all her life), her education was broader than that of her other sisters. Like several of her sisters, Napoleon considered Anna a marital prospect. The Romanovs were intent on Napoleon not marrying into the Russian Imperial family. Anna’s mother delayed her response until Napoleon’s interest in Anna faded (and he turned it to Austrian Archduchess Marie Louise, whom he eventually married.)

Anna was an excellent dynastic match as well as beautiful and intelligent. After considering several illustrious matrimonial prospects (the prospective Bourbon heir, the Duc de Berry, and the British Duke of Clarence), her brother Tsar Alexander I arranged her marriage to William of Orange, who would later become King William II of the Netherlands (making Anna his Queen.) She married William at the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. Her dowry was one million rubles.

The couple remained in Russia for one year before leaving for the Netherlands (her governess accompanied her.) Anna had problems adjusting at first, and although she came to enjoy her life in Brussels, where the nobility liked her, she always considered herself, first and foremost, a Russian Grand Duchess. She always believed she had married beneath her station. Hot-tempered and seen as elitist, Anna lamented that she could not have remained in Russia, which she visited frequently.

Her only political role as the crown princess was mediating between her husband and his father. She considered her role as a royal woman to be predominantly in charity and was very involved and successful. She founded a charity commission and a school in needlework for poor women and girls and gave financial contributions to the Anna Paulowna and Sophia schools. After the death of her mother-in-law in 1837, she took over the protection of the charity “mother foundations.” She founded a hospital in The Hague for wounded soldiers, whom she visited regularly.

As Queen, she would never be popular and remained distant from the public; however, because she greatly valued court etiquette and ceremony, the Dutch court reportedly acquired more “royal allure” during her tenure.

Anna’s marriage was stormy; her husband was unfaithful. However, she always supported him in public. They had five children: William (on whom she focused her attention as the heir and who she unsuccessfully tried to dominate), Frederick Henry, Alexander (her favorite), and Sophia (who would eventually be the Grand Duchess of Weimar-Eisenach). She was a devoted mother. Anna eventually separated from her husband. Despite this, she continued to advise him and acted as his Queen Consort.

Anna Pavlovna died from a respiratory ailment. On the death of her husband in 1849, Anna was bereft and found it hard to come to terms with the loss of her official standing. She suffered financial difficulties as queen dowager and lived in quiet seclusion, constantly clashing with King William III and her daughter-in-law.

Post link

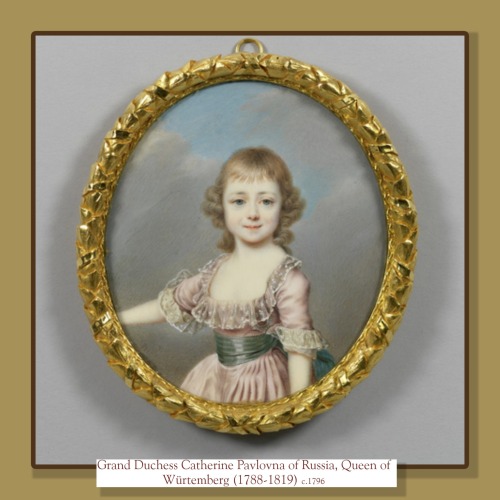

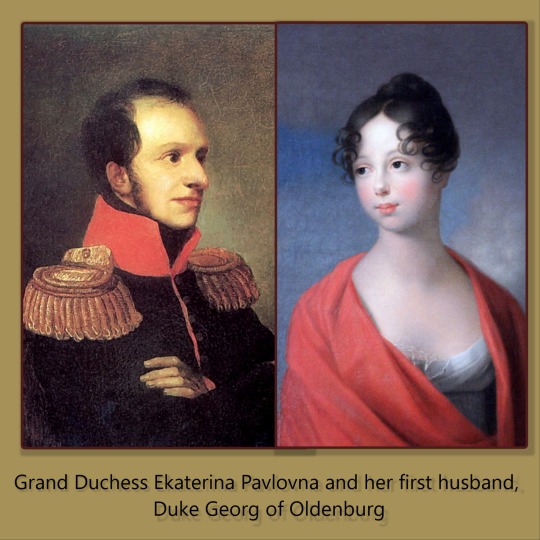

The Grand Duchesses: The daughters of Tsar Paul I: Part IV: Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna (1788- 1819)

The fourth daughter and sixth child of Emperor Paul I and Empress Maria Feodorovna was named “Ekaterina” after her paternal grandmother, Catherine the Great. Her family called her “Katya.” She was born at the Catherine Palace in Tsarkoe Selo. Like her sisters, she received a good education. She loved to read. She was said to have been beautiful and had a pleasant and vivacious personality.

Katya was close to her brother Alexander I. They remained close throughout her life. Ekaterina was Alexander’s favorite sister and one of the few persons he loved unconditionally. In his letters to her, he includes phrases like “I am yours, heart and soul, for life,” “I think that I love you more with each day that passes,” and “to love you more than I do is impossible.” Although Paul and Maria Feodorovna were initially disappointed at the birth of a fourth daughter, Ekaterina later became her mother’s favorite daughter.

At one point, Napoleon Bonaparte, who needed a young and suitably high-born bride to provide him with an heir and had decided to divorce Josephine, showed an interest in Ekaterina. The union would have been advantageous to Napoleon in more than one way. Still, its prospect horrified Ekaterina’s family, who promptly arranged for the young woman to marry a maternal cousin, Duke Georg of Oldenburg (1784-1812). Their descendants became the Russian branch of the Oldenburg.

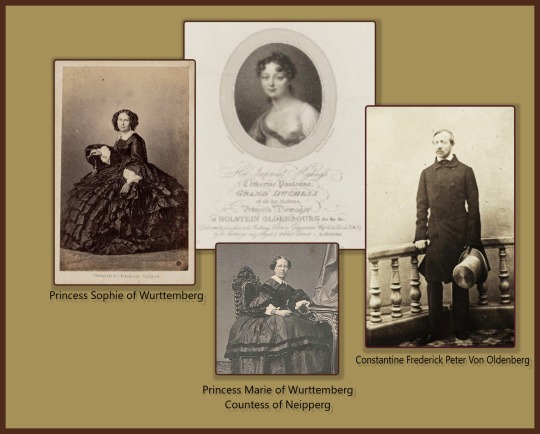

Although the marriage had been hastily arranged, the bride and groom seemed compatible. They had two sons: Peter Georg (b. 1810 – I could not find any paintings or photographs of him - he died at age 19) and Constantine Friedrich Peter (b. 1812). The couple resided in Tver, where George had been appointed governor-general. Catherine lived a lavish court life and entertained with balls, grand dinners, and similar events in the pattern of the Russian court to create “a Small Saint Petersburg” in Tver. Like her sister Maria, she greatly enriched the cultural life of her adopted country. Unfortunately, Ekaterina’s husband died of typhoid barely three years into the marriage.

During the years immediately after the death of her husband, Ekaterina stayed with her siblings and traveled with her brother Alexander I; she traveled to England with him to meet the future George IV and accompanied him to the Congress of Vienna.

In England, Ekaterina met the Crown Prince Wilhelm of Württemberg (1781-1864). They fell in love at first sight. However, Wilhelm was already married to princess Caroline Augusta of Bavaria. Crown Prince Wilhelm and Caroline Augusta sought and got an annulment of their marriage; apparently, no love was lost between them; their marriage had been an unsuccessfully arranged one, and after its dissolution, Caroline Augusta married Emperor Franz of Austria as promptly as Wilhem married Ekaterina.

The couple’s first daughter was Princess Marie Friederike Charlotte, who was born on the same day that her grandfather died, and her father acceded to the throne of Wurttemberg; her mother thus became Queen Katharina of Württemberg. As Queen, Ekaterina supported elementary education and organized a charity foundation during the hunger of 1816. In 1818, she gave birth to another daughter, Sophie Frederike Mathilde, who would marry Ekaterina’s nephew Willem III of Orange and become Queen of the Netherlands.

While researching this piece, I read two different versions of the causes of Ekaterina’s death. Ekaterina dies of erysipelas (not caught on time) complicated by pneumonia at Stuttgart in the first one. In the second version, Ekaterina travels to Italy, where he finds her husband with a mistress (although he loved Ekaterina, he had not given up “dalliances”). Heartbroken, Ekaterina returns home not caring to dress warmly enough and catches pneumonia that kills her at age thirty.

What is certain is that Ekaterina died six months after the birth of her youngest child, leaving four small children scattered across two families behind. Her (perhaps) unfaithful and surviving husband, built Württemberg Mausoleum in Rotenberg, Stuttgart, dedicated to her memory. He promptly married his first cousin, Pauline of Wurttemberg.

Post link

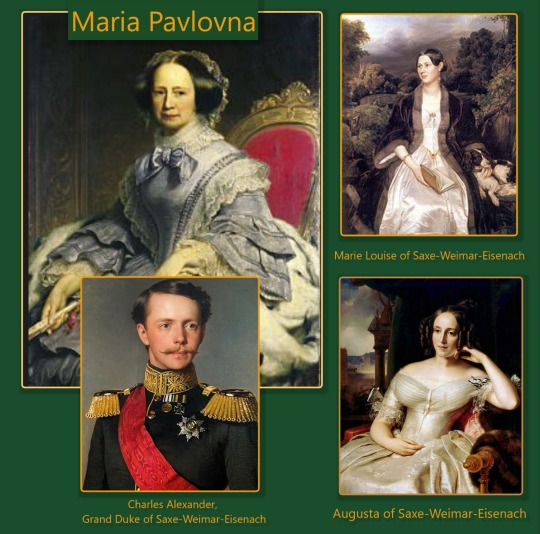

The Grand Duchesses: The daughters of Tsar Paul I: Part III: Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (1786 - 1859) “The Pearl of Russia”

Maria Pavlovna was the third daughter of Emperor Paul I. Although Catherine the Great was still alive when the little girl was born, the parents finally got to name one of their children after the mother (Maria Feodorovna!) - Catherine had chosen the names for their first daughter (Alexandra in honor of Paul’s older son, the future Alexander I) and their second daughter (Elena, after Helen of Troy because the little girl was so beautiful.)

When Maria was a very young child, she was given a vaccine for smallpox as a result of which she contracted the disease. She was left badly scarred, so she was not pretty as a youngster. She was an intelligent, forward, tomboyish child, leading Catherine the Great to say that, because of her marred looks and her personality, she should have been born a man. But by the time she was an adolescent, the scarring had faded, and “Masha,” was considered pretty, if not beautiful. Although she was forceful, she was also cheerful and social. Maria became a gifted pianist and painter. Through her love of reading and studying she also became very cultured. All of these qualities lead her to be her father’s favorite daughter. He called her “The Pearl of Russia.”

In 1803, Prince Charles Frederick, heir to the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach was invited to Russia, as part of the negotiations for a possible marriage between him and Maria. He spent almost a year in Russia, getting to know his future bride. They proved to be compatible and were married in Pavlovsk. The couple spent their honeymoon in Pavlovsk and from there Maria and her husband headed to her new home.

She was received in Weimar with great joy. Weimar was a poor but very cultured country. The court and the intellectuals fell in love with the Russian Grand Duchess, who seemed to have the gift to charm everybody. With her arrival at Weimar, the small country underwent a cultural re-awakening.

Unfortunately, the arrival of Maria in Weimar coincided with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte in France and during the succeeding years, the duchy found itself under constant threat due to Napoleon’s expansionist ambitions. They had to leave their country several times but always returned. Weimar benefited from its close association with Russia through their adoption of Maria as one of their own and probably remained independent because of it.

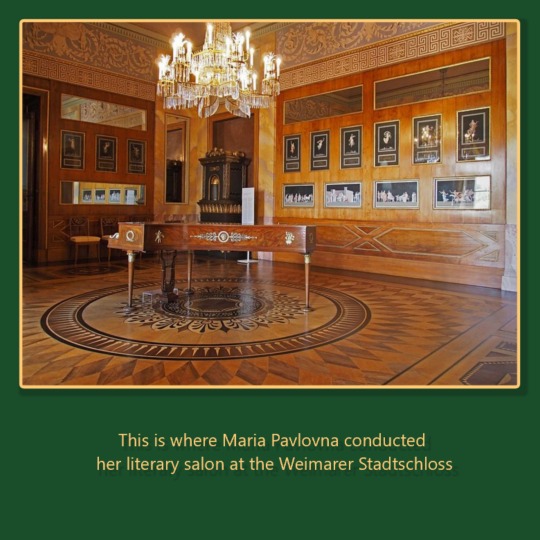

Maria never stopped studying. Through her life she corresponded with several famous writers, poets and painters. She conducted very popular literary evenings (or “salons”) in her home. She became a patroness of the arts, science and social welfare. She founded a museum. She supported the establishment of a horticultural institute as well as the creations of workhouses and training programs for the poor. She was called the “Angel of the Poor.” Goethe declared her one of the greatest and most outstanding women of his time.

Maria Pavlovna always maintained strong ties to her Russian family. Her opinions on Russian affairs were valued and taken into consideration. She was considered a second mother to her younger siblings including Nicholas I, who always held her in great regard. Maria was very affected by his untimely death. Her last visit to Russia was for the coronation of her nephew, Alexander II.

Her marriage was not perfect because her husband’s interests were different hers, but he considered her an asset and they remained together until his death in 1853.

Maria and Friedrich had four children: 1. Paul Alexander, who died when he was a baby, 2. Marie Louise Alexandrine of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, who married Karl of Prussia, 3. Augusta Louisa Katherine of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, who married Wilhem I and became German Empress and 4. Karl Alexander August Johann of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. After her husband died, she retired from public life.

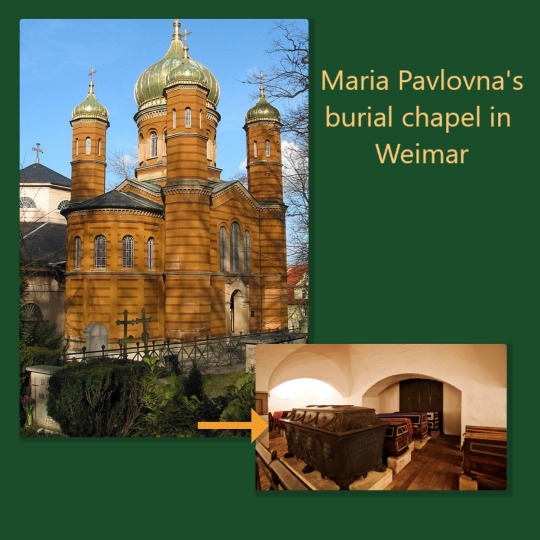

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna died at age 73, six years after her husband. She is buried in Weimar.

Post link

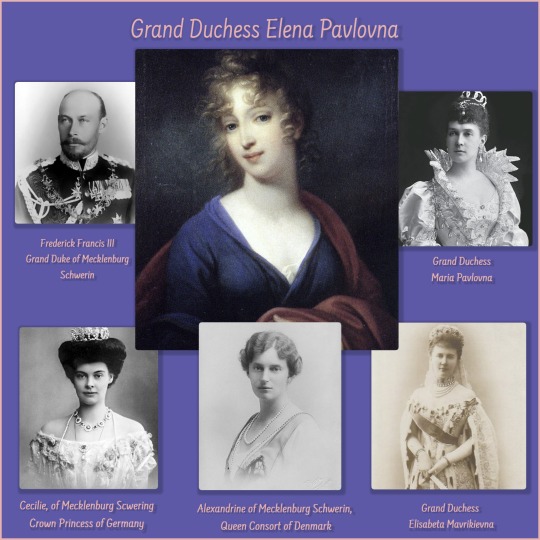

The Grand Duchesses: The daughters of Tsar Paul I: Part II: Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna (1784 - 1803)

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna was Tsar Paul’s third child and second daughter. She was born in Saint Petersburg, less than a year after her sister Alexandra. The Grand Duchesses were very close and their lives seem to have run along similar paths.

Elena, like Alexandra, was born when Catherine II (the Great) was still alive. Catherine named the child after Helen of Troy; this was a reference to the little girl’s great beauty. Initially Catherine thought that Elena was a more attractive child than Alexandra (it seems that later on Alexandra became the favorite.) While Catherine was at the helm of Russia, Paul and his wife Maria Feodorovna did not even get to name their children.

Negotiations for Elena’s marriage began when she was still a child. The bridegroom selected came from one of the small duchies which were part of the Holy Roman Empire at the time and which later would be absorbed by Germany. His name was Prince Friedrich Ludwig of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

Hereditary Prince Friedrich Ludwig of Mecklenburg-Schewerin was described by a Russian courtier as “a handsome man but essentially rustic and ignorant, although a good person.”

The couple married at Gatchina Palace. At the time, marriages among nobles usually took place in the country of origin of the groom. Only Russian Grand Duchesses were allowed to sidestep this custom and usually married in Russia. Elena’s title after her marriage was Hereditary Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

Elena had two children, Grand Duke Paul Friedrich of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Marie Louise of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

Elena’s life was as brief as her sister’s Alexandra. The Hereditary Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin married at age 15 (1799), had her first child at age 16 (1800) and her second child at age 19 (1803); she died that same year, several months after the birth of her son. Some sources mention that she died suddenly, of an unknown malady, others state that she might have had tuberculosis. She is interred in the “Helena Paulovna” Mausoleum in Ludwigslust

The Grand Duchess gave the Romanov and the Schwerin lines a number of well known descendants. I have highlighted a few below.

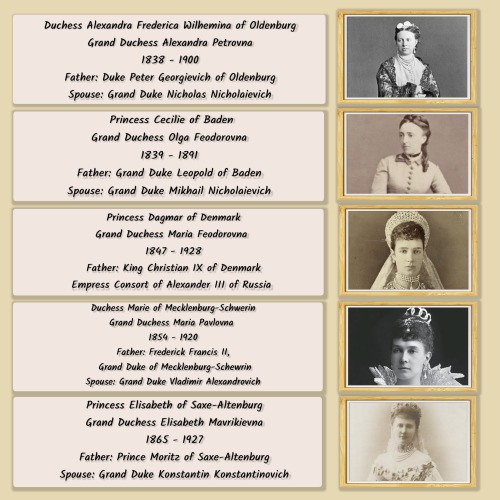

- Princess Elisabeth of Saxe-Altenburg was Elena Pavlovna´s great-granddaughter and therefore descended from Tsar Paul I. She added additional Romanov blood to her line by marrying Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich and becoming Grand Duchess Elisabeta Mavrikievna.

- Princess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was Elena Pavlovna´s great-granddaughter and also descended from Tsar Paul I. She married Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich and boasted of her Pauline descent by choosing the name Pavlovna at the time of her marriage.

- Maria Pavlovna´s brother was likewise Elena Pavlovna´s greatgrandson. Frederick Francis was the Hereditary Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin when he married Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna, daughter of Grand Duke Mikhail Nikolaievich (who was Tsar Paul’s grandson). He eventually became Frederick Francis III.

- Frederick Francis III´s daughter, Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin great-granddaughter once removed of Elena Pavlovna on the paternal line and Tsar Paul’s great-grandaughter once removed on the maternal line, married into Keiser Wilhem Il’s family and became the last Crown Princess of Prussia.

- Frederick Francis III other daughter, Alexandrine of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, was also a great-granddaughter once removed of Elena Pavlovna and a great-granddaughter once removed of Tsar Paul. She became the Queen Consort of Denmark when she married Christian X. She is the great-grandmother of the current Queen of Denmark, Magrethe II, who is, therefore, also related to Elena Pavlovna!

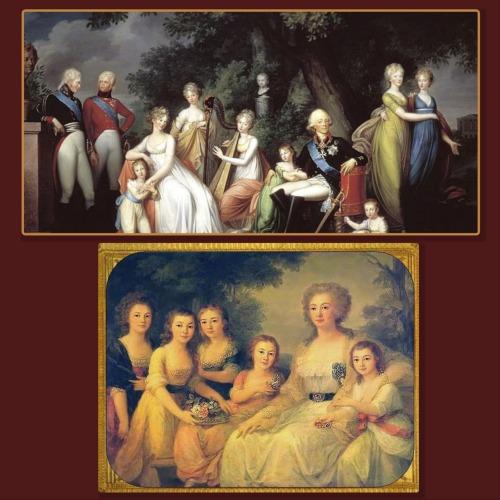

Photographs/Illustrations: 1. Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna; 2. The Grand Duchess’ Grandmother, Catherine the Great, and her Parents, Paul I and Maria Feodorovna; 3 and 4: Elena Pavlovna; 5. Elena and her older sister Alexandra; 6. Elena Pavlovna and her husband Hereditary Prince Friedrich Ludwig of Mecklenburg-Schwerin; 7. Elena Pavlovna; 8. Elena Pavlovna’s children, Grand Duke Paul Friedrick of Meckleburb-Schwerin and Marie Louise of Mecklenburg-Schwering; 9. Some of the descendants of Elena Pavlovna.

Post link

The Grand Duchesses: The daughters of Tsar Paul I

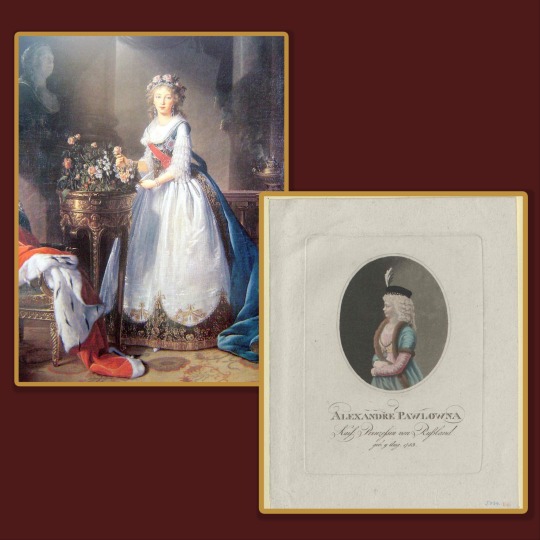

Part I: Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna (1783 - 1801)

Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna was the eldest daughter of Tsar Paul I of Russia and his second wife, Empress consort Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Wurttemberg). Catherine II of Russia (the “Great”) was among her illustrious grandparents.

The Grand Duchess was born in Tsarskoye Selo while Catherine the Great was still alive. She had four brothers (the future Tsar Alexander I and Tsar Nicholas I were among them) and five sisters. The difference in ages between Alexandra and her sister Elena was barely one year and they were very close. There are paintings of the sisters together.

Alexandra’s education was similar to that of other princesses; it revolved around art, music and languages. She spoke Russian, English and German. She was expected to marry for dynastic reasons. By the time Alexandra was eleven years old, negotiations had been started for her to marry Gustav IV of Sweden. Gustav visited Russia and met Alexandra when she was about thirteen; they liked each other (Alexandra is described as tall, intelligent, beautiful and charming.) The marriage never happened. Negotiations broke off over the matter of religion. The Swedish required their future queen consort to convert to Lutheranism; the Russian side did not agree to Alexandra’s conversion.

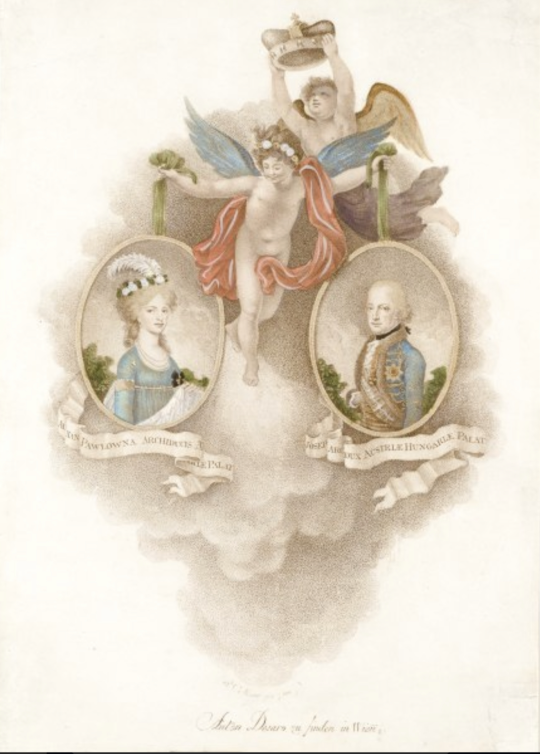

Three years later, at the age of sixteen, Grand Duchess Alexandra was married off to Archduke Joseph, Palatine (Governor) of Hungary (a younger brother of Emperor Francis II of Austria.) This is the only Romanov-Hapsburg marriage on record. The bride and groom were compatible, but their happiness was not destined to last.

Some sources (most notably her confessor, Andrei Samborsky) report that Alexandra was not happy at the Austrian court. Although she was allowed to continue to practice her Orthodox faith, this was generally frowned upon by the catholic Austrians. Also, she reminded Empress Marie Therese of the Emperor’s first wife (with good reason, the first wife had been Alexandra’s maternal aunt); because of this and Alexandra’s beauty, as well as the sumptuous jewels the Grand Duchess had brought from Russia, the Empress was jealous of Alexandra. It is unlikely that she did very much to make the young woman feel welcomed in her new country.

Fortunately, Joseph and Alexandra did not reside in Vienna all the time; their seat was in Hungary. The Grand Duchess became very popular among the Hungarian nobility because she re-invigorated court and cultural life; Alexandra liked to wear Hungarian typical dress. The poor loved her because of her beauty and her generosity.

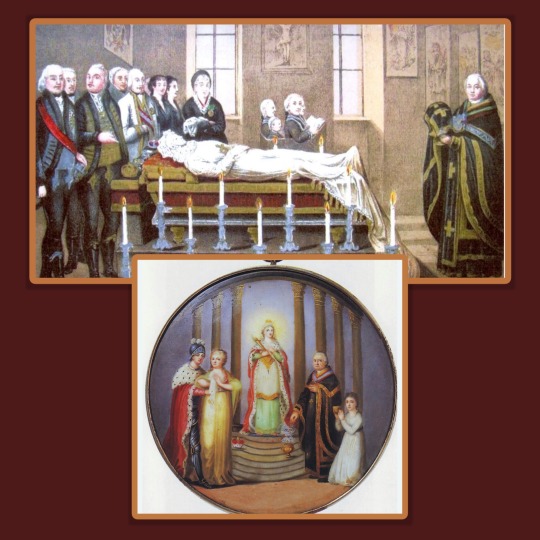

Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna died in Buda of child-bed fever at the age of seventeen, after giving birth to a daughter who did not survive. She died within a week of her father, Tsar Paul l of Russia.

Alexandra was buried in a mausoleum built by her husband near Pest. The mausoleum became a place of pilgrimage for the Orthodox community in Hungary. Her remains rested in Buda Castle for a time after the mausoleum was desecrated. In 2004 they were returned to the Urm Mausoleum. There is a monument built in her honor in Pavlovsk, which was dedicated to her around 1810.

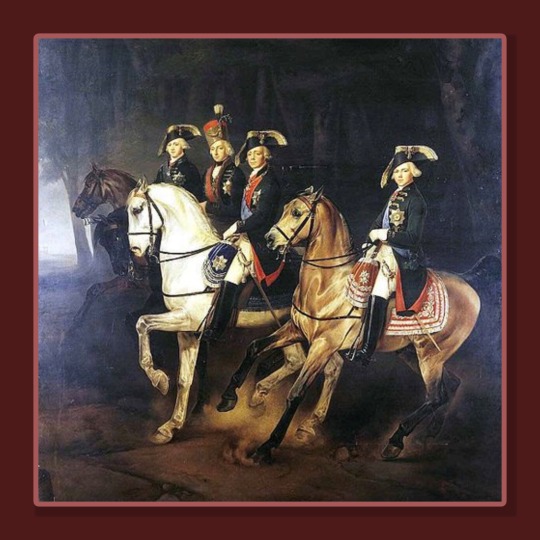

Photographs: 1. Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna as a young child; 2. Top: Tsar Paul and his family (the two young women arm and in arm to the right are most likely Grand Duchesses Alexandra and Elena; Bottom: Empress Maria Feodorovna and her daughters; 3. Grand Duchesses Alexandra and Elena; 4. Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna - notice the absence of jewelry; 5. Betrothal or Wedding announcement for Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna and Archduke Joseph of Austria; Tsar Paul, his two eldest sons and Archduke Joseph of Austria (to the his right); 6 and 7: Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna; 8. Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna in Hungarian dress; 9. The Grand Duchess laying in state; her confessor appears all the way to the right; 10. Allegorical painting of the Grand Duchess; her mausoleum in Hungary became a pilgrimage site for the Orthodox community in Hungary. Her confessor and his daughter appear to the right; there is no consensus as to who the two figures to the left represent although I have read that they may be Alexander I and the Grand Duchess’ mother, Empress Maria Feodorovna; 11: Monument dedicated to Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna in Pavlovsk

Post link

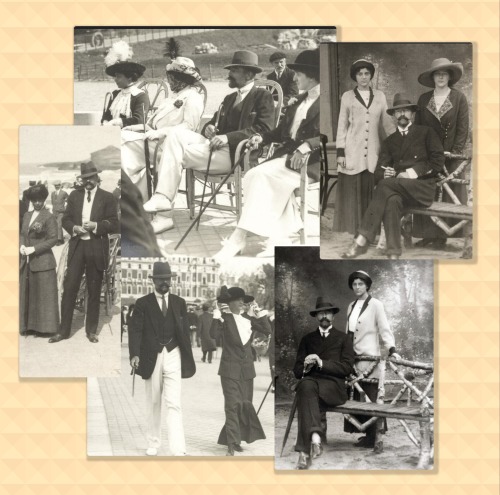

His Imperial Highness Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia.

Most likely in Biarritz (at least in the exteriors) during those years he spent out of Russia “in disgust” after the crew of his ship mutinied. Luckily, he was off the ship tending to a very sick child; his sailors’ plans were to take him hostage. Nicholas II asked him to resign (basically to prevent a member of the ruling family from being kidnapped.) Sandro went ahead and took time off to do some of his favorite things (digging at Ai Todor, playing golf, buying himself new clothing, hats, shoes and attending dinner parties). He also decided to use the time to have a middle age crisis and get himself a mistress. I think that the fact that he decided to do so while Xenia was pregnant with their last child (and felt compelled to tell her) was in extremely poor taste.

This is very tongue in cheek…the events took place, but the order may not bear close scrutiny.

Post link

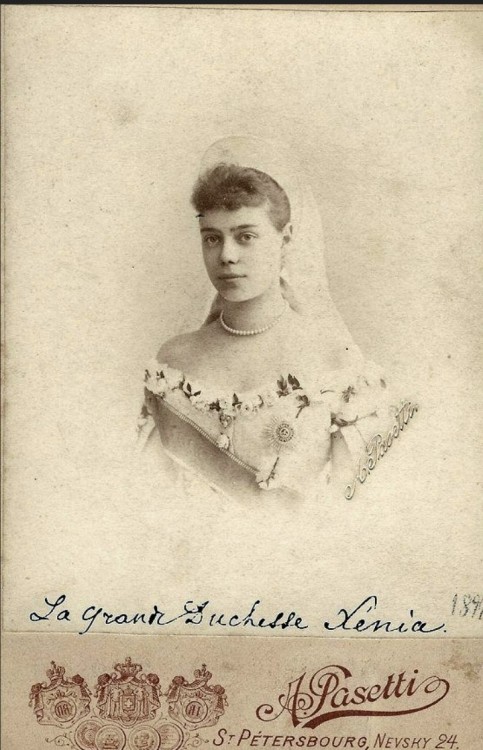

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna Romanova (1875 - 1960) - Part 3 of 3

When the revolution that removed the Romanovs from power broke out, Grand Duchess Xenia, Grand Duke Sandro, their children and a number of other Romanovs including the Dowager Empress, Grand Dukes Nicholas and Peter Nicholaievich and their families and entourages, headed for the Crimea (not necessarily together.) After a period of more or less pleasant exile, they were all placed under house arrest by the Bolsheviks, first at Ai Todor, Sandro’s house, and later at Dulber, Peter Nicholaievich’s palace. Their jailers’ intentions were to eventually liquidate them. In an interesting twist of fate, the group was liberated by the Germans. Just in the nick of time, George V sent a war ship to rescue his aunt. Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, not only insisted on taking her immediate family along, but filled the ship with other Russians seeking to escape the country.

Maria Feodorovna died in exile leaving the portion of her jewelry collection she had been able to get out of Russia and other limited assets to her daughters (in her will she provided for her servants as well, but not for her son Mikhail ‘s widow or for Mikhail’s son.)

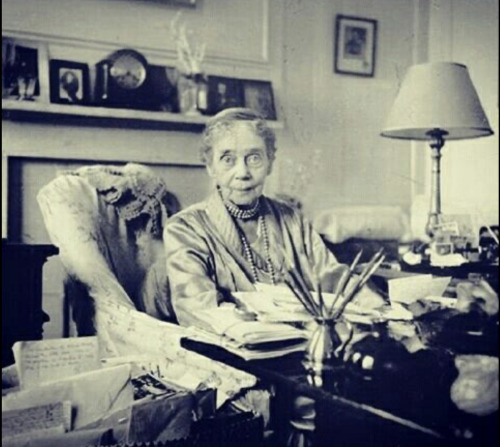

Xenia and Sandro’s marriage was now beyond repair (although, contrary to what he says in his memoirs, there are letters indicating he tried to convince Xenia to go back to him.) Grand Duke Alexander established himself in Paris. He lived off his coin collection and wrote three fairly successful books before his death. Grand Duchess Xenia settled in England, under the “auspices” of her cousin George V. The King offered the Grand Duchess Frogmore Cottage at Windsor in 1925. This helped Xenia’s financial situation; she had no independent income and had no idea of how to administer whatever little she had; after she lost precious resources to a scam, King George assigned an administrator to look after Xenia’s finances. Upon the death of King George V in 1936, Xenia was advised that Frogmore Cottage was now intended for use only by the immediate royal family. Thus the grace and favour lodgings of Wilderness House at Hampton Court became her home until her death.

Through the rest of her long life (she lived to age 85) she was heavily involved in multiple charitable causes to benefit the Russian community in exile. She remained very close to her cousins Victoria of Wales, who visited frequently, as well as to Queen Maud of Norway and Marie of Greece and Denmark. They all pre-deceased her. Queen Mary was also a regular visitor. Xenia maintained a voluminous correspondence with her relations and friends disseminated through Europe.

At any given time, Xenia had one or more of her children, along with their spouses and their offspring, living with her. She also seems to have sent money to some of them periodically. Her older sons Andre and Feodor both suffered from tuberculosis. Xenia was a grandmother and great grandmother many times over.

Until the end of her days, she preserved her elegance, grace and impeccable manners. During Sandro’s final illness, she travelled to France with Irina to be at his bedside. He died in his daughter’s arms while Xenia was at a function being given in her honor. Xenia is buried with the husband she never divorced at Cimetière de Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in the South of France

Photographs: 1. Grand Duchess Xenia and her mother, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna; 2. Xenia and her daughter Irina; 3. Grand Duchess Xenia; 4. Granduchess Xenia aboard the warship on which she left Russia forever; 5. Xenia and Sandro; 6. Grand Duchess Xenia with her fully grown children, Irina, Andrei, Feodor, Nikita, Dmitry, Rostislav and Vasily. 7. Xenia with her companion Mother Martha, a Russian nun who moved to Wilderness House in 1938. She was loyal and fiercely protective of Xenia. When Xenia died Mother Martha disappeared without a trace, along with the inheritance left to her by the Grand Duchess; 8. Xenia with her grandson Prince Alexander, Princess Margarita of Baden and their daughter Olga; 9. Wilderness House; 10. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna at her desk.

Post link

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna Romanova (1875 - 1960) - Part 2 of 3

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna and Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich got married in 1894. Unfortunately, her wedding was the last public event Tsar Alexander III attended. They married in August and the Tsar died in November. Xenia’s brother Nicky ascended to the throne of Russia as Nicholas II and married Princess Alix of Hesse, who became Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

The two couples developed a very close relationship. Sandro held important posts during Nicholas II’s reign but he does not seem to have acquired the influence he should have as the Tsar’s brother-in-law, a relationship that placed him in extremely close proximity to the seat of power. The relationship between Nicholas and Alexandra and Sandro and Xenia was, indeed, a close one during the first few years of their marriage, yet it eroded slowly. The reasons for this are multiple and varied. Xenia and Sandro’s lifestyle was not as “sheltered” as Nicholas and Alexandra’s. Also, as the Empress gave birth to four beautiful girls in succession, Xenia’s first born daughter Irina was followed by six consecutive healthy sons. This could not have been a comfortable state of affairs for Alexandra who was eager to produce just one boy and seemingly could not. Although this was probably not the determinant factor in the cooling of her relationship with her sister in law, it must have contributed to it. What doomed the relationship was the fact that as the young Empress gained influence over Nicholas, his mother, the dowager, lost hers; Xenia sided with her mother. And let us not forget the gradual involvement of the imperial couple in matters related to mysticism (first in the guise of Monsieur Phillipe, and much later through the person of Rasputin) an interest not at all shared by Xenia and Sandro at that point.

Xenia and Sandro’s marriage seems to have been a love match. Given Grand Duke Alexander’s restless personality, it is no surprise that he would eventually find other love interests. The grand-ducal couple spent long periods of time outside of Russia, making the rounds of Biarritz, Cannes, etc with their ever expanding brood in tow. During Xenia’s pregnancy with her last child, Grand Duke Alexander fell in love with a Spanish/Italian woman we only know as Maria Ivanova, who was a frequent guest at the parties Xenia and Sandro gave. He decided to come clean to Xenia, and they opted to live “together but apart” for the sake of the children. They never got a divorce although Sandro asked Xenia for one several times through the years. The affair with Maria Ivanova lasted a number of years. Afterwards, there were other women in Sandro’s life; Xenia also took a lover (whose identity is not known for sure; there is speculation that this lover was an Englishman we know only as “Fane;” while others mention Prince Sergei Dolgoruky, an adjutant to the Dowager Empress - it is possible that these are two individuals Xenia had relationships with at different points in time.) Although both Sandro and Xenia were extremelly discreet, the state of their marriage was more or less an open secret. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna greatly pitied “poor litte Xenia with that terrible husband.”

Xenia and her mother remained very close. The Dowager Empress came to depend on Sandro and grew particularly close to Xenia’s children, especially beautiful, ethereal Irina. She derived all the enjoyment from these grandchildren that she could not from her son Nicholas’ offspring, since her contact with them was limited.

When World War I erupted, Xenia, Sandro, Maria Feodorovna, Irina, who by now was married to the eccentric Prince Felix Yusupov (one of the richest men in Russia) were all out of Russia. They hurried back home to serve their country for what they did not know would be one last time.

Photographs: 1. Illustration of different “scenes” from Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna’s wedding to Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (this was the last public event that Alexander III was able to attend due to his final illness.) 2. A very young Xenia (she must have been between 18 and 19 years old) holding her first born child and only daughter Irina); 3. Grand Duchess Xenia wearing a beautiful and very becoming boyarina costume; 4. Formal portrait of Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna; 5. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna at sea 6. Xenia and Sandro with their seven children, Irina, Andrei, Feodor, Nikita, Dmitry, Rostilav and Vasily; 7. Grand Duchess Xenia and her children; 8. Xenia, her daughter Irina and her granddaughter Bebe; 9. Xenia and Sandro with friends; 10. Xenia, a very dapper Sandro and entourage in Biarritz

Post link

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna Romanova (1875 - 1960) - Part 1 of 3

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna was the fourth child and first daughter of Emperor Alexander III and his wife, Empress Maria Feodorovna. Her mother was eager to have a girl after her three boys, Alexander (who died as a baby), Nicky, and Georgy. Her parents and siblings received Xenia with great joy.

Xenia was born into the lap of luxury, during a time when her parents, who were not yet Emperor and Empress, had less social and state commitments and more time to devote to their children. Her childhood was genuinely idyllic. She grew up surrounded by cousins, who became playmates and lifelong friends (such as Marie, Princess of Greece and Denmark and Victoria of Wales) and even found a husband (Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich) among these childhood companions. European royalty of the time was almost all related, not only through Queen Victoria but also through Queen Louise and King Christian IX of Denmark, Xenia’s maternal grandparents, who were known as the “mother and father-in-law of Europe;” these extended families got together every year, and the royal children had a chance to form lasting relationships.

Xenia received the education typical of an aristocratic girl of her time, which concentrated on languages, drawing (she was as talented as her mother and sister Olga), and music. She took gymnastics lessons and was somewhat of a tomboy (despite her delicate and refined appearance.) She resembled her mother physically but her personality was not as gregarious; she was shy with strangers. In her letters, one can appreciate an intelligent, curious, friendly woman. All her life, she would be involved in many charitable causes (giving to others even when she was not in a position to do so anymore.) However, her generosity and good works did not seem to get as much publicity in her case as in that of other Russian female royals, perhaps because her roles were usually administrative and she did not have to wear a uniform.

By the time Xenia was sixteen, she knew she wanted to marry her cousin Alexander Mikhailovich. It is possible that the appeal of such a union resided not only in the dashing person of Sandro but also on the fact that the marriage would allow Xenia to stay in Russia rather than result in her contracting a dynastic union outside of it. Her parents made the couple wait until she was nineteen. Interestingly enough, Alexander was not the only Mikhailovichi who desired Xenia Alexandrovna’s hand in marriage. Sandro’s younger brother Sergei was also in love with the young grand duchess. Did Xenia ever questioned her choice of brothers later on in her life?

Xenia met and befriended Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine when they were both adolescents and they wrote to each other; it seems that Xenia did whatever she could to propitiate a union between the pretty princess and her brother Nicholas; the girls called each other “Chicken” (Xenia) and “Hen” (Alix). They would remain friendly even after their respective marriages, although the relationship eventually soured.

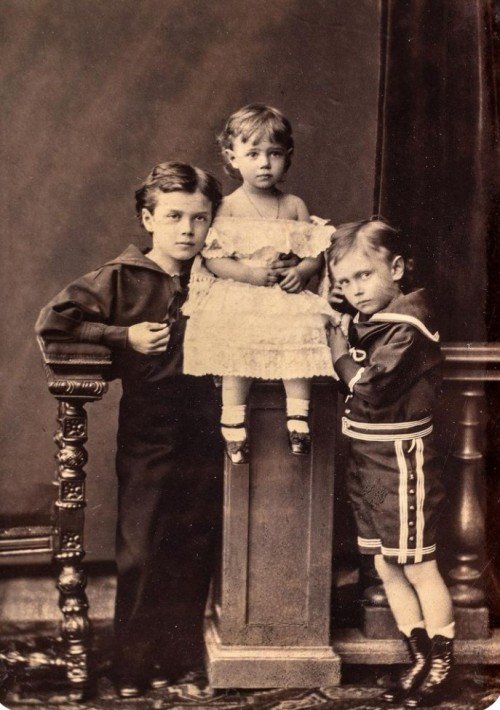

Photographs: 1. Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna with her mother, Tsarevna Maria (she was born before her father became Tsar and her mother Tsarina); 2. Grand Duchess Xenia with her older brothers, the Grand Dukes Nicholas and George; 3. Grand Duchess Xenia with her younger brother Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (I wish I knew the dog’s name); 4. Grand Duchess Xenia and her younger sister Grand Duchess Olga (the only one of Alexander III’s children to be born “in the purple;” 5. Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna with Xenia and Misha; 6. A nubile Xenia wearing Russian court dress; 7. Life- long friends Grand Duchess Xenia and her cousin Princess Marie of Greece and Denmark (the future “Grand Duchess George” after her marriage to Grand Duke George Mikhailovich who was an older brother of Xenia’s husband, Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich); 8. Grand Duchess Xenia and her cousin, Victoria (”Toria”) of Wales; 9. From left to right, Olga, Nicholas, Xenia and the future George V; 10. Empress Maria Feodorovna (looking incredibly young) and Grand Duchess Xenia with Grand Duke Alexander (Sandro) Mikhailovich

Post link

Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871 - 1899)

Tsarevich George Alexandrovich appears here with his cousins Maud and Victoria of Wales in the south of France. These photos were taken in 1896, three years before his death. He looks like the aristocratic, refined young man he was, and although he seems frail, he is still handsome.

Source: vk.com/britishroyalty (X)

Post link

Grand Duke Sergei Mikhailovich, or as I call him, “the Grand Duke with the sad blue eyes.” He loved Mathilde Kschessinska, Nicholas Il’s ex-mistress almost a life-time but in the end, she married Grand Duke Andre Vladimirovich instead. Sergei was murdered by the Bolshevicks.

Post link

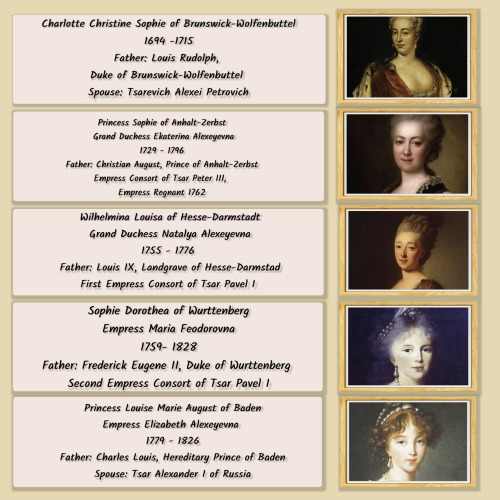

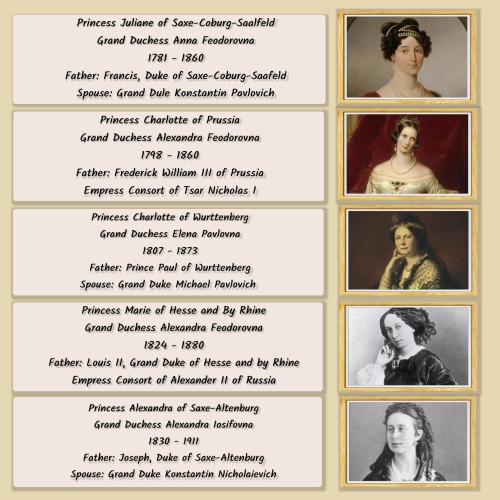

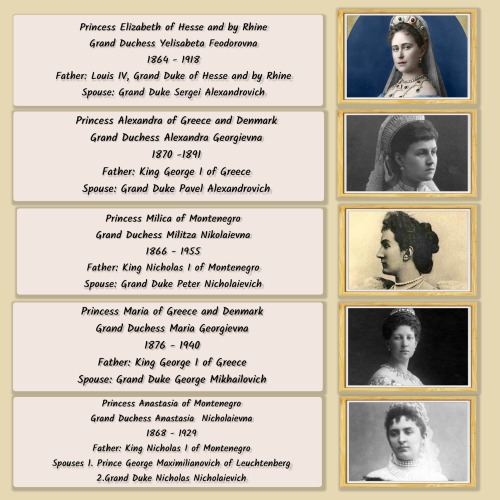

Russian Grand Duchesses (Velikaya Knyaginya) - Part II: Grand Duchesses by Marriage

These are the Grand Duchesses of Russia who gained the tittle by marriage to a Grand Duke of the House of Romanov. They were styled “Her Imperial Highness.” Grand Dukes were required to make “equal marriages,” that is, they had to marry into other reigning families. This was done as part of strategic diplomacy and to benefit national interests.

According to the laws of the House of Romanov (originally known as Pauline Laws), which were amended over time, Grand Dukes had to ask for the Tsar’s permission to marry. A marriage with a person not coming from a ruling family would be termed “morganatic.“ A morganatic marriage was considered one to a man or woman of lower social station and/or not from a reigning house. In Tsarist Russia, if the marriage was acknowledged as legal at all, the spouse of lower rank would not acquire the tittle of the spouse of higher rank and the children from the marriage would not have succession rights.

During his time as Tsar, Nicholas II had to contend with multiple members of his family marrying morganatically. His own stance on the issue of equal marriages was very strict. The Grand Dukes asked him to amend the laws; he did this at the end of his reign. Nicholas II legalized authorized marriages of Imperial Romanovs below grand ducal rank (those who were not sons or grandsons of a Tsar) to spouses who lacked “corresponding rank.” The Grand Dukes continued to be required to marry into ruling houses.

Post link

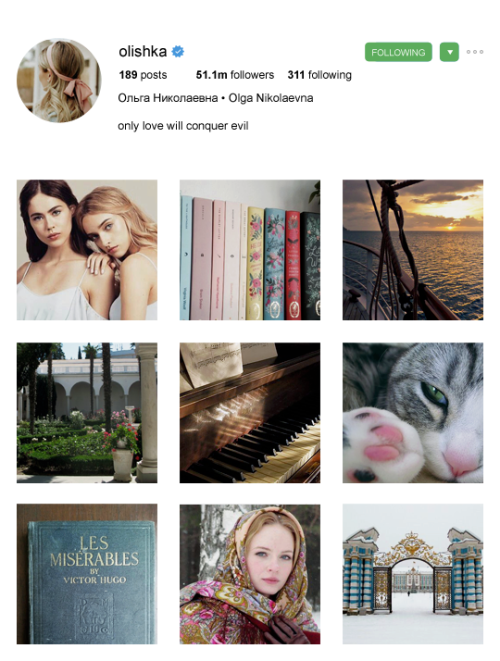

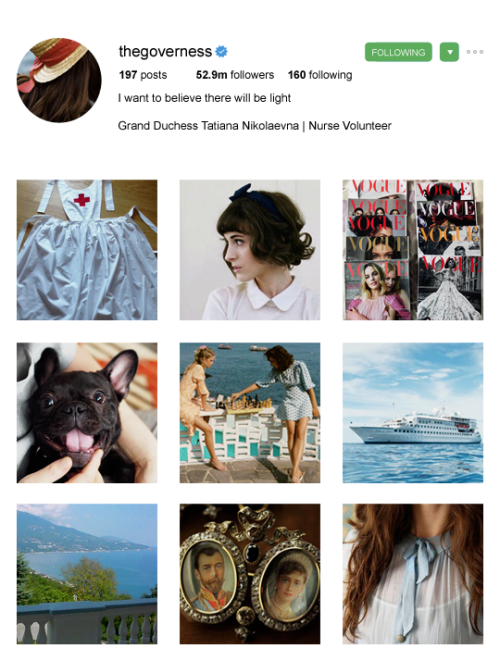

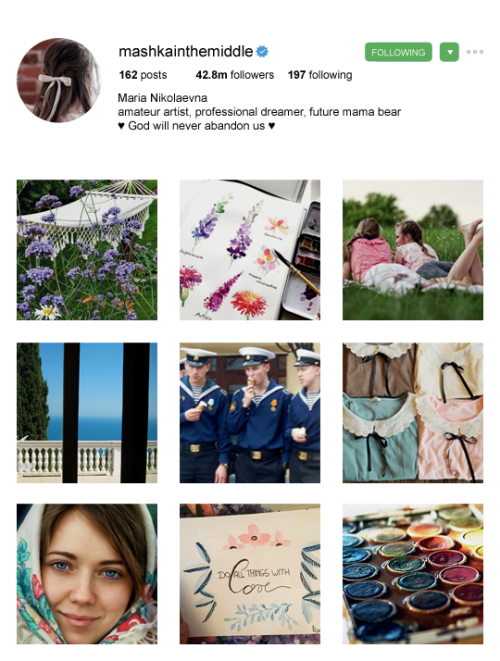

historical women + instagram|olga,tatiana, maria, and anastasia nikolaevna romanova

happy (belated) birthday @tiny-librarian!

Post link