#transliteration

A lot of foreign names are a bit…clunky when transliterated into Chinese. For example:

- 莱昂纳多·迪卡普里奥 lái’ángnàduō·díkǎpǔlǐ’ào = Leonardo DiCaprio

- 埃米纳姆 āimǐnàmǔ = Eminem

- 泰勒·斯威夫特 tàilè·sīwēifūtè = Taylor Swift

I’m not going to dive into why—that’s a whole other post. But some of these transliterated names are seriously hard for me to say! And it seems like Chinese fans agree, because they have shorter nicknames for some foreign celebs.

The three celebs I mentioned above each have nicknames. I actually encountered all three nicknames while watching Chinese TV shows recently! So I can confirm that they are really used. Can you tell who is who?

- 小李子 xiǎolǐzǐ

- 阿姆 āmǔ

- 霉霉 méiméi

But where did these nicknames come from? What do they mean?

Leonardo DiCaprio / 小李子

The transliteration above starts with 莱 (lái), but transliterations are not universal. According to what I found online, 李奥纳多 is an alternative transliteration of Leonardo. As an American English speaker, I think this sounds closer to how I say Leonardo. So the nickname 小李子 likely comes from 李奥纳多. 小李子 is certainly much easier to say than 莱昂纳多·迪卡普里奥.

Eminem / 阿姆

Interestingly, even though the simplified Chinese Wikipedia page for Eminem is titled 埃米纳姆, the body text uses both 埃米纳姆 and 阿姆. But the traditional version only uses 阿姆. The Baidu page only uses 埃米纳姆. 阿姆 is not only shorter and easier to say, but 阿+syllable is a known nickname structure, so my guess is that’s where 阿姆 came from.

Taylor Swift / 霉霉

According to these 百度知道 comments, Taylor Swift is called 霉霉 because 1) 霉 sounds like 美 and 2) she used to be unlucky when it came to charting on Billboard (霉 in this case as in 倒霉, to have bad luck/be out of luck). I would have guessed it was because she had bad luck in finding love honestly! You’ll have to decided for yourself which origin story you believe.

Some of my past posts about Chinese names seem to have become popular among people in the writing community (writeblr???) as references. I’m very happy that people are interested in learning about Chinese names to name their original characters! However, I’m sure some people are also interested in creating characters of the Chinese diaspora. The diaspora is HUGE, but I wanted to shed some light on Chinese American names.

Disclaimer: I am just one Chinese American drawing on the stories of my family, friends, and classmates. This can’t certainly represent all Chinese Americans, so keep that in mind. My focus is primarily on people born and/or raised in the US as opposed to adult immigrants. I imagine a lot of this post also applies to Chinese Canadians, Chinese Australians, etc.

Name Formats

Our lovely “model” for today will be the fictional character of Jane/Jiayi Wang (王佳怡). Here are some basic name structures I’ve encountered throughout my life:

- Jane Jiayi Wang

One very typical name format would be Western first name, Chinese middle name, last name. I don’t have any actual data on it, but if you told me that this format was the most common for US-born Chinese Americans, I would believe you. Today, it feels like I’m seeing more and more people use their Chinese middle names alongside their Western first names professionally or on social media. - Jiayi Wang

Some Chinese Americans do not have a Western-style name. This could be the case for someone born in the US or someone who immigrated. Often people with this name format may go by a Western name like Jane even if it’s not part of their legal name. They could also go by an abbreviation of their Chinese name or a nickname derived from their Chinese name. - Jane Wang / Jane Amelia Wang

Not all Chinese Americans have a Chinese name as part of their legal name. Some might have Western first and middle names. Someone without a Chinese name as part of their legal name might still have a Chinese name that just isn’t “official,” or they might not have a Chinese name at all. - Jiayi Jane Wang

I don’t think this name format is as common as the ones above. I’ve definitely seen people who immigrated as adults use this format, maybe if they adopted a Western name for convenience but still want to use their native name. However, the name they go by may not reflect their legal name. - Jane Li-Wang / Jane Li Wang

These examples (which are rarer in my experience) incorporate both parents’ surnames, one by hyphenating and the other by making one parent’s surname the middle name. I’ve read that recently in China, a growing number of parents (but still a small number) are passing on both surnames (like 李王佳怡).

While I don’t personally know many people who fit this description, sometimes parents will select Chinese and Western names that are similar. This could be a loose similarity like Jane/Jiayi or a closer similarity like Lynn/Lin(g). Take for example the pair Eileen/Ailing, as in Eileen Chang (张爱玲) or Eileen Gu (谷爱凌). Another example of a close match is Wilber Pan/Pan Weibo (潘玮柏).

Another option is a Chinese name as a first name that was picked to be easy for English speakers to pronounce. Names like Ming or Kai are short and easy to pronounce.

More on Chinese Names

- As I said, not all Chinese Americans have a Chinese name. For some, this might not be a big deal, but for others, it could be a sensitive issue.

- Some have a Chinese name but may not know how it’s written, what it means, etc. A lot of Chinese Americans are mostly illiterate in Chinese and may not feel very comfortable speaking the language either. In my experience, it’s not uncommon for Chinese Americans to only be able to write their Chinese name and nothing else. There’s literally a whole song about this phenomenon.

- Sometimes one may not know their Chinese name at all. Some Chinese Americans rarely if ever use their Chinese name. They may even feel little or no connection to the name. If their parents were born in the US or immigrated at a young age, it’s likely the Chinese name was given by grandparents. In this situation, it’s possible the parents don’t know the Chinese name of their child either.

- Some Chinese Americans are interested in reclaiming their Chinese name. I’ve seen people add their Chinese names to their social media or even consider switching to going by their Chinese name.

- Others don’t like being made to feel like a Western name such as Jane isn’t their real name (perpetual foreigner stereotype, anyone?). Acting like Jane isn’t someone’s “real name” and you must uncover their “more authentic” Chinese name is very icky. Jane and Jiayi are both real and valid.

Important: Due to some of the reasons above (and probably others) some Chinese Americans may not like it when others ask them about their Chinese names. It may be something very personal that they prefer to keep private, something they feel no connection to, something they don’t have in the first place, etc.

Also, someone isn’t turning their back on their heritage because they prefer going by Jane over Jiayi. While it’s true that some people feel pressured into going by a Western name that’s easier for others to pronounce (and this SUCKS), no one should be forced to go by their Chinese name if they don’t want to. People should respect and learn to pronounce others’ names, but as I’ve seen pointed out on Twitter, some people would rather go by Jane than have to hear Jiayi butchered day after day. So always respect personal choice and don’t pressure others to adopt a Western name or go by their Chinese name against their will.

Adopting Mispronunciations: Liu, Wang, Zhang, Zhao, etc.

I know Chinese Americans who pronounce their names or surnames “incorrectly” to conform with American English pronunciations of these names. For example, take Bowen Yang (杨伯文) or Lucy Liu (刘). I’ve also observed bearers of common surnames Wang, Zhang, and Zhao going by the Americanized pronunciations of their surnames.

Sometimes this can be a little confusing because I’m honestly not sure if I should pronounce their name the Americanized way or the native Chinese way. For instance, I had a classmate who reluctantly pronounced her surname Liu more like Lu but wished people would say it more accurately. But I also had another classmate with the last name Wang who didn’t seem to care about the pronunciation.

Romanization

This post wouldn’t be complete without mentioning that Chinese American names are diverse when it comes to romanization system used. First of all, there are many Chinese languages. Secondly, you have people immigrating from different countries with different romanization standards. Additionally, practices change over time, so people whose ancestors immigrated decades ago might have a name that uses a romanization system no longer in use. I’m sure there are even people whose full names contain traces of multiple romanization systems.

After writing most of this post, I came across an interesting piece by Emma Woo Louie, Name Styles and Structure of Chinese American Personal Names. (She also has a whole website about Chinese American surnames!) The article is almost 30 years old, but it was an interesting read and still relevant today. It includes a discussion on the different ways to write two-syllable names.

- Separated by a space

- With a hyphen between

- No separation

For our example Jane Wang, you might expect to see:

- Jane Chiayi Wang

- Jane Chia Yi Wang

- Jane Chia-yi Wang

- Jane Chia-Yi Wang

I used Wade-Giles style romanization above because that’s what I typically see used alongside hyphens. Learn more about it by reading another post of mine!

Emma Woo Louie’s article also mentions the use of initials (like J.Y. Wang/C.Y. Wang for our example). I initially did not think to include this name format—I think it’s less in style now and it didn’t occur to me—but I have encountered it before.

I have also met Chinese Americans whose surnames were altered accidentally during the immigration process, thus leaving families with “misspelled” surnames. Certainly makes for an interesting family story!

Adoptees

Disclaimer: I’m not an adoptee and do not want to speak over adoptees. But I wanted to add a section on adoptee names. Thinking back, most Chinese adoptees I’ve met do not have anything in their legal name that is Chinese, but there are exceptions to this—I do know some who have names of the format Jiayi Smith or Jane Jiayi Smith.

A former classmate of mine knew the story and meaning behind her name (it was given by the workers at the orphanage she was adopted from), but I don’t know how common her experience is. My assumption is that most adoptive parents don’t know Chinese, so they probably won’t know much about their child’s Chinese name, and thus the child might not know much either.

I’ve read some essays and other thoughts by adoptees about their relationships with their Chinese names that I’ll link below. I encourage you to check them out!

Names | 姓名 by Kimberly Rooney | 高小荣

Twitter thread by Lydia X. Z. Brown

Stuck in Racial Limbo by Hazel Yafang Livingston

Multiracial Chinese Americans

For multiracial Chinese people, there is a whole world of other possibilities for names, but a lot of what I wrote above can apply as well. Every person and family is different! Here are just a few general trends I’ve observed:

- Non-Chinese first name plus legal Chinese middle name *

- Has Chinese name that isn’t part of legal name *

- No Chinese name at all *

- Has mother’s maiden name as a middle name +

- Hyphenated surname

- I’m sure there are multiracial Chinese people with Chinese given names, but in my experience, it’s not common here

*Surname may or may not be of Chinese origin

+If mother is Chinese and father is not

Following typical naming conventions here, it’s more likely someone has a Chinese surname if their father is Chinese, but this isn’t true in all cases. In the case that someone has their father’s non-Chinese surname, they might use their mother’s Chinese surname in situations where they are going by their Chinese name. Like Jane Jiayi Smith might use her mother’s surname 王 and go by 王佳怡 in Chinese class, even thought Wang doesn’t appear in her legal name.

Fellow Chinese diaspora folks, feel free to add on with contributions about names of the diaspora in your country/community/family/etc.!

A Guide to Taiwanese Name Romanization

Have you ever wondered why there are so many Changs when the surname 常 is not actually that common? Have you ever struggled to figure out what sound “hs” is? Well don’t worry! Today we are going to go over some common practices in transliterating names from Taiwan.

With some recent discussion I’ve seen about writing names from the Shang-Chi movie, I thought this was the perfect time to publishe this post. Please note that this information has been compiled from my observations–I’m sure it’s not completely extensive. And if you see any errors, please let me know!

According to Wikipedia, “the romanized name for most locations, persons and other proper nouns in Taiwan is based on the Wade–Giles derived romanized form, for example Kaohsiung, the Matsu Islands and Chiang Ching-kuo.” Wade-Giles differs from pinyin quite a bit, and to make things even more complicated, transliterated names don’t necessarily follow exact Wade-Giles conventions.

Well, Wikipedia mentioned Kaohsiung, so let’s start with some large cities you already know of!

[1] B → P

台北 Taibei → Taipei

[2] G → K

[3] D → T

In pinyin, we have the “b”, “g”, and “d” set (voiceless, unaspirated) and the “p”, “k”, and “t” set (voiceless, aspirated). But in Wade-Giles, these sets of sounds are distinguished by using a following apostrophe for the aspirated sounds. However, in real life the apostrophe is often not used.

We need some more conventions to understand Kaohsiung.

[4] ong → ung (sometimes)

[5] X → Hs or Sh

高雄 Gaoxiong → Kaohsiung

I wrote “sometimes” for rule #4 because I am pretty sure I have seen instances where it is not followed. This could be due to personal preference, historical reasons, or influence from other romanization styles.

Now some names you are equipped to read:

王心凌 Wang Xinling → Wang Hsin-ling

徐熙娣 Xu Xidi → Shu/Hsu Hsi-ti (I have seen both)

黄鸿升 Huang Hongsheng → Huang Hung-sheng

龙应台 Long Yingtai → Lung Ying-tai

宋芸樺 Song Yunhua → Sung Yun-hua

You might have learned pinyin “x” along with its friends “j” and “q”, so let’s look at them more closely.

[6] J → Ch

[7] Q → Ch

范玮琪 Fan Weiqi → Fan Wei-chi

江美琪 Jiang Meiqi → Chiang Mei-chi

郭静 Guo Jing → Kuo Ching

邓丽君 Deng Lijun → Teng Li-chun

This is similar to the case for the first few conventions, where an apostrophe would distinguish the unaspirated sound (pinyin “j”) from the aspirated sound (pinyin “q”). But in practice these ultimately both end up as “ch”. I have some disappointing news.

[8] Zh → Ch

Once again, the “zh” sound is the unaspirated correspondent of the “ch” sound. That’s right, the pinyin “zh”, “j”, and “q” sounds all end up being written as “ch”. This can lead to some…confusion.

卓文萱 Zhuo Wenxuan → Chuo Wen-hsuan

陈绮贞 Chen Qizhen → Chen Chi-chen

张信哲 Zhang Xinzhe → Chang Shin-che

At least now you finally know where there are so many Changs. Chances are, if you meet a Chang, their surname is actually 张, not 常.

Time for our next set of rules.

[10] C → Ts

[11] Z → Ts

[12] Si → Szu

[13] Ci, Zi → Tzu

Again we have the situation where “c” is aspirated and “z” is unaspirated, so the sounds end up being written the same.

曾沛慈 Zeng Peici → Tseng Pei-tzu

侯佩岑 Hou Peicen → Hou Pei-tsen

周子瑜 Zhou Ziyu → Chou Tzu-yu

黄路梓茵 Huang Lu Ziyin → Huang Lu Tzu-yin

王思平 Wang Siping → Wang Szu-ping

Fortunately this next convention can help clear up some of the confusion from above.

[14] i → ih (zhi, chi, shi)

[15] e → eh (-ie, ye, -ue, yue)

Sometimes an “h” will be added at the end. So this could help distinguish some sounds. Like you have qi → chi vs. zhi → chih. There could be other instances of adding “h”–these are just the ones I was able to identify.

曾之乔 Zeng Zhiqiao → Tseng Chih-chiao

施柏宇 Shi Boyu → Shih Po-yu

谢金燕 Xie Jinyan → Hsieh Jin-yan

叶舒华 Ye Shuhua → Yeh Shu-hua

吕雪凤 Lü Xuefeng → Lü Hsueh-feng

Continuing on, a lot of the conventions below are not as consistently used in my experience, so keep that in mind. Nevertheless, it is useful to be familiar with these conventions when you do encounter them.

[16] R → J (sometimes)

Seeing “j” instead of “r” definitely confused me at first. Sometimes names will still use “r” though, so I guess it is up to one’s personal preferences.

任贤齐 Ren Xianqi → Jen Hsien-chi

任家萱 Ren Jiaxuan → Jen Chia-hsüan

张轩睿 Zhang Xuanrui → Chang Hsuan-jui

[17] e → o (ke, he, ge)

I can see how it would easily lead to confusion between ke-kou, ge-gou, and he-hou, so it’s important to know. I’ve never seen this convention for pinyin syllables like “te” or “se” personally.

柯震东 Ke Zhendong → Ko Chen-tung

葛仲珊 Ge Zhongshan→ Ko Chung-shan

[18] ian → ien

[19] Yan → Yen

I’ve observed that rule 18 seems more common than 19 because I see “yan” used instead of “yen” a fair amount. I’m not really sure why this is.

柯佳嬿 Ke Jiayan → Ko Chia-yen

田馥甄 Tian Fuzhen → Tien Fu-chen

陈建州 Chen Jianzhou → Chen Chien-chou

吴宗宪 Wu Zongxian → Wu Tsung-hsien

[20] Yi → I (sometimes)

I have seen this convention not followed pretty frequently, but two very famous names are often in line with it.

蔡英文 Cai Yingwen → Tsai Ing-wen

蔡依林 Cai Yilin → Tsai I-lin

[21] ui → uei

I have seen this convention used a couple times, but “ui” seems to be much more common.

蔡立慧 Cai Lihui → Tsai Li-huei

[22] hua → hwa

This is yet another convention that I don’t always see followed. But I know “hwa” is often used for 华 as in 中华, so it’s important to know.

霍建华 Huo Jianhua → Huo Chien-hwa

[23] uo → o

This is another example of where one might get confused between the syllables luo vs. lou or ruo vs. rou. So be careful!

罗志祥 Luo Zhixiang → Lo Chih-hsiang

刘若英 Liu Ruoying → Liu Jo-ying

徐若瑄 Xu Ruoxuan → Hsu Jo-hsuan

[24] eng → ong (feng, meng)

I think this rule is kinda cute because some people with Taiwanese accents pronounce meng and feng more like mong and fong :)

权怡凤 Quan Yifeng → Quan Yi-fong

[25] Qing → Tsing

I am not familiar with the reasoning behind this spelling, but 国立清华大学 in English is National Tsing Hua University, so this spelling definitely has precedence. But I also see Ching too for this syllable.

吴青峰 Wu Qingfeng→ Wu Tsing-fong

[26] Li → Lee

Nowadays a Chinese person from the Mainland would probably using the Li spelling, but in other areas, Lee remains more common.

李千那 Li Qianna → Lee Chien-na

[27] Qi → Chyi

I have noticed this exception. However, I’ve only personally noticed it for this surname, so maybe it’s just a convention for 齐.

齐秦 Qi Qin → Chyi Chin

齐豫 Qi Yu → Chyi Yu

[28] in ←→ ing

In Taiwanese Mandarin, these sounds can be merged, so sometimes I have noticed ling and lin, ping and pin, etc. being used in place of each other. I don’t know this for sure, but I suspect this is why singer A-Lin is not A-Ling (her Chinese name is 黄丽玲/Huang Liling).

[29] you → yu

I personally haven’t noticed these with other syllables ending in “ou,” only with the “you” syllable.

刘冠佑 Liu Guanyou → Liu Kuan-yu

曹佑宁 Cao Youning → Tsao Yu-ning

There is a lot of variation with these transliterated names. There are generally exceptions galore, so keep in mind that all this is general! Everyone has their own personal preferences. If you just look up some famous Taiwanese politicians, you will see a million spellings that don’t fit the 28 conventions above. Sometimes people might even mix Mandarin and another Chinese language while transliterating their name.

Anyway, if any of you know why 李安 is romanized as Ang Lee, please let me know because it’s driving me crazy.

Note: The romanized names I looked while writing this post at were split between two formats, capitalizing the syllable after the hyphen and not capitalizing this syllable. I chose to not capitalize for all the names for the sake of consistency. I’m guessing it’s a matter of preference.

Seriously, somebody please tell me how the hell “Sean” could be pronounced as “Shawn.”

Because Seán is an Irish name and thus the laws of Irish orthography and phonology apply to it. In Leinster, Munster, and Connacht Seán is pronounced “Shawn” because the letter “s” (broad/velarised) is sounded as the English “sh” (slender/palatised) when it is followed by the letter “e” or the letter “i”. The “e” is present to indicate the pronunciation of the “s”, and so remains unsounded. As the name is originally spelt “Seán”, with a fada, it has a long a, which is the “aw” sound. In Ulster, pronunciation differs; I believe “Shane” is more common.

Hello, you’ve been reblogged by etymologic because you’re talking sense! Hope you don’t mind! (If you do, say so and we’ll delete this reblog.)

On a more general note: people, when it seems like something in the English language doesn’t ‘make sense’, it’s a good idea to remember these two points before going off about it:

- Is the word that doesn’t 'make sense’ originally an English word? If not, the translation / transliteration of that word may have been like trying to fit a round peg in a square hole: awkward and with casualties.

- English is not the first language this alphabet was assigned to (it’s called the Roman alphabet for a reason), and as such, it’s a little silly to pretend as though the rules of our language– of our particular interpretation of this alphabet, which we did not invent for the language we use it with– are the last word on the subject.

Or, in short:

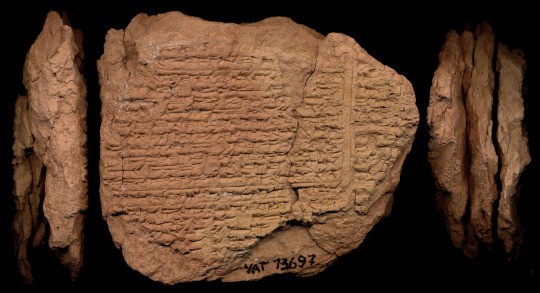

This is an excerpt from a lengthy Akkadian ritual that we know from multiple tablets, all of them unfortunately broken. The ritual starts by describing the patient: he is constantly depressed and has other physical symptoms, from pain to nausea. Such symptoms are clearly a sign that he has been attacked by witchcraft. To combat the witchcraft, the ritual practitioner relies on a combination of magical actions (such as burning figurines of the magicians who caused the illness) and prayers to Shamash, the Sun-god, who represents an all-seeing force of justice.

This is the first of the incantations recited by the practitioner. Below the cut, I’ve included the transliteration of the incantation (in case anyone wants to try it) and a short comment on the untranslated word “Namraṣit.”

I call to you, Shamash. Listen to me!

Accept my sleepless sighing.

Learn swiftly of the suffering that seizes me.

I am sluggish; I am sleepless; I am exhausted; I am anxious.

I focus on Namraṣit, your light, o my lord.

Shamash, lord of justice, to you I turn.

Pay attention to my lifted hands; listen to my speech.

Listen to me; accept my petition;

judge my case; decide my verdict.

alsīka Šamaš šimânni

muḫur tānīḫīya šudlupūti

marušti imḫuranni limad arḫiš

anḫāku-ma šudlupāku šūnuḫāku šutaddurāku

ana namraṣīt nūrīka upīq bēlī

Šamaš bēl dīni ana kâša asḫurka

ana nīš qātīya qūlam-ma šime qabâya

šimânni-ma mugur teslītī

dīnī dīn purussâya purus

Note:In Abusch and Schwemer’s translation, they translate Namraṣit as “who-shines-for-me-at-rising” (namra-ṣit), clearly intended to be an epithet for Shamash. But Namraṣit is a known name, and it’s used elsewhere for Sin, the Moon-god. The question is whether this line (the exact midpoint of the incantation) belongs to the first half, where the symptoms are described, or the second half, where Shamash is invoked. In other words, is the speaker saying that he focuses on Shamash as a source of justice, or is he saying that he focuses on the moon as a sign of sleepless depression? I am unsure.