#written word

My Grandpa Gary is a rebel, that’s what he says. He is loud and crass; he will say exactly what he thinks at any given moment, without hesitation. If you ask him something, he answers honestly with no thought of subtlety or fear of consequence.

Oddly enough, the rebel I know is part of one of the most reserved families I have ever seen. While he was off doing whatever was considered inappropriate to them in the early sixties, his mother, Katie; step-father; and brother probably continued to eat breakfast and dinner at their proper place settings, they may have prayed, and they certainly didn’t speak about what Grandpa Gary might be up to. Somehow, I can’t imagine them really communicating much; least of all when it came to Grandpa’s biological father, Herman, and why he, apparently, didn’t exist anymore.

It never occurred to me that some rogue part of my parentage had seemingly disappeared into the great vat of rice that is the world’s population. I didn’t realize that the great-grandfather I had always known was only a that by of marriage. No one ever spoke about it. I suppose I did wonder how Grandpa Gary could fit into their family portrait. Between his quick lips and his avid nature to roam, there was a distinct contrast. His home was any city, town, or campground; a truck and trailer, and the open road. He had three companions. Two dogs: one large, shaggy and black named Bear, the other a protective part wolf named Shoshona. The last was a short, thin woman with dark hair and an amazing knack for entertaining his grandchildren with “This piggy went to the market…” - well, it entertained me. They only made an appearance in our lives every once in a while, but to see them was the most amazing treat. I don’t remember a time before this group, so if Grandpa Gary had ever been clean cut and unspoken, I have trouble picturing it.

As I got older I started to see the differences between my Grandpa and his family. Around the same time, my mom became very interested in our ancestry. Being more exposed to Gary than to his family had fostered in my mom and me, a proclivity toward curiosity and the idea that something might be a secret made it more important to uncover. With unrivaled tenacity, she found Grandpa’s real father, Herman Moon, in Texas but she found him too late.

Grandpa Gary’s mother, Katie, would not talk about Herman, not in detail, and she was the only one we knew with any knowledge of him. Why Herman left and why he never came back, why he never called or wrote, why he never cared was lost. Any questions would be brushed off and deeper inquiries were met with rigid silence.

Years later, Mom got in touch with a woman named Dorothy. Dorothy was Herman’s niece from a second marriage and Dorothy knew a lot. A lot by our standards, anyway, and she had no problem talking.

I’ve always heard that cliché phrase about a woman scorned and thought it trite and silly. I’d never seen a woman in such a rage she would thoroughly ruin the offenders life in some form or another. I couldn’t quite capture the image in my head of Katie having a wrath, let alone executing it. Yet, when Grandpa Gary was around two years old, Katie was admitted into a hospital where she stayed for treatment of what is assumed to have been a venereal disease. I’ll never know for sure, but the belief is that Herman had been having an affair. When Katie was released she took Grandpa and went to her parents’ without Herman. She didn’t go back.

They divorced and Herman moved to San Francisco. He married a woman named Mildred but he never forgot his son. Katie had never told us that Herman had decided to try for custody or visitation of Grandpa Gary. When he and Mildred showed up at her house they were greeted with shotgun and told not to come back. They went home to California, but Herman didn’t give up. He handed a lawyer five thousand dollars and asked him to help. Nothing ever happened and Dorothy never heard him speak about the lawyer again. We’d never heard of the lawyer at all.

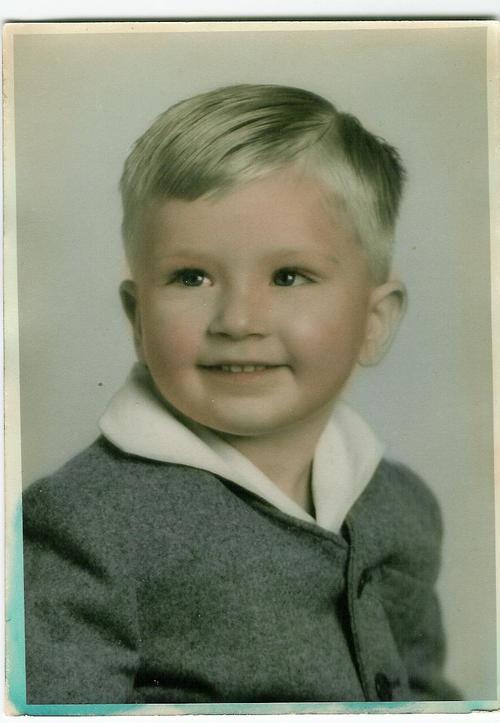

Herman never stopped talking about his son, though. Dorothy said he kept a picture he’d had taken of Grandpa in focal points of his house without fail. He was so proud of whatever his son could have been; it probably never really mattered to him what, exactly, it was.

This is the part of the story where I imagine Herman’s side of the family. I can picture his sisters so clearly, standing in their kitchens, talking to Herman over the phone. I picture them asking after a particularly awkward silence “So, have you heard from Katie? Anything about Gary Lee?” And when I think of his response I think of a silent head shake and a very clipped “No.” That is the end of the conversation, in my head. They say quick goodbyes and hang up. Then maybe Herman spends a drawn out moment looking at that picture of his son, frozen in his mind at two years old.

Herman and Mildred divorced, but they stayed in touch and Dorothy remained a big part of his life. He worked in finishing carpentry in Hollywood. He married a third and final time. He must have messed around on this woman as well, because when she left, she took everything.

Dorothy found him his own place where he lived until he died, with Grandpa’s picture in the forefront. As his days dwindled, he began to ask her if she’d found or heard anything about Gary Lee. Only a few months after Herman died, mom found him, or rather his obituary, online. When she did, she cried. She had just missed him.

When I got home the day she spoke to Dorothy, Mom was restless. She didn’t look me in the eye, and I could see a million images passing behind her own. After she rambled off the entire story, she exhaled any confidence she may have had and told me she had no idea how she was going to tell Grandpa Gary. She had no idea how she was going to let him know after all those years of stolid silence, how loved he was. How wanted.

When Mom did talk to Grandpa, all she could do was give him Dorothy’s phone number and tell him to call. Dorothy sent him the watch that Herman had been wearing when he’d died and a few of the pictures that she had.

Neither of these things can rewrite time. Herman would never know his rebel son who roamed around the country, the granddaughter that tracked him down, or the great-granddaughter that is writing about him now. My Grandpa Gary will never know his father, only that the man had never stopped looking for him, never stopped wanting him. Only that, if he had been able too, Herman would have been and done anything for Gary. My mom will never know her grandfather, she’ll only ever have photos to pour over and memorize and second hand stories to think about before she falls asleep. I will never sit next to him, close my eyes, and listen to the tone and pacing of his voice as he talks about the people he’s known and the places he’s been. Now it isn’t the whys that we will never know, it is the hundreds of stories lost between us all. The stories, I think, we would have gladly shared, good or bad.

Grandma Katie passed in 2009, taking her justification with her, locked tight away. I can’t say if she ever knew that we’d found Herman and what was left of his family. I can’t say that she knew he’d died. More than anything, I can’t say she ever forgave him or if her scorn went away. I’ll never understand why an affair may have caused her to separate her son from his father. Perhaps there was more to it that we’ll never know.

Katie was a private woman who held her head high and stuck to her decisions like she’d made them with crazy glue. The last time I saw her, she was in a nursing home in Tennessee. She had been injured getting out of bed and as a result, hadn’t walked in weeks. But on that day, as we were leaving the home, we watched as she scurried down the hall with her walker and yelled at the physical therapist to hurry up.

I don’t remember her as the woman who kept her son from his father or who kept her tongue like using it would create a crack in the Earth that the sky would crumble into. I remember her as the woman who did what she thought was right to protect herself and her son, though I find myself wishing she hadn’t have been so stubborn about Herman. Whether he was a great or terrible, sometimes it’s better to cope with disappointment instead of uncertainty. Sometimes, some decisions are not yours alone. Sometimes they have the ability to vastly alter someone else’s world. But when you’re caught up in the moment, sometimes you just have to decide to speak or remain silent. The art in it is to know when you might have decided incorrectly and when to concede.