#nonfic

I am notorious for caring too much. I invest all of myself into the people around me and my mistake is that I expect that investment back. In my short short years on this planet, I have learned more things than I would have cared to. I learned that I can change myself to fit someone else’s version of ‘cool’. I’ve learned that asking or accepting help is the most difficult thing one can face. I have learned that I will almost always love someone more.

After I gave up on Christianity, I took up the religion of love and compassion. It was all I needed. It would guide me. But just like any other crisis of faith, there are times of incredible doubt. There are times when my idyllic world views just don’t align with what’s happening.

When I say someone is my friend, I am saying that we support each other. That there is an equality that towers over and transcends tally marks and scores. I hold comfort my roommate as they deal with alcohol poisoning and they don’t hate me for having my bike in the middle of the living room for two days. I help them move and they leave me incredibly sweet notes when they know I’m anxious or depressed. No action is more or less than the other because every action is thoughtful and applicable to what is needed.

I choose friends in the same way I would choose my family, if I had the option. The part of my brain that allows me to feel close to someone - that allows me to let go of control around them, is incredibly underdeveloped. It takes a lot, so when that is betrayed or is revealed to be one sided, it devastates the system.

My best friend has known me since we were five years old and I have only one memory of life before her. Even so, it wasn’t until we were 13 that I really relied on her.

I always loved my dad more than he ever loved me. It’s a heartbreaking truth, but a truth nonetheless.

Back to love, though. When you really get down to it, take into account the love I feel for people and every ounce of their potential and ever moment of their rich, beautiful past, I would die for every single person I have ever seen and will ever see.

I care that much for people who couldn’t pick me out of a line up. I can’t think of a way to measure how much I care for the people I consider my friends.

With that thought in mind, there is no way I can participate in human relationships without experiencing immense pitfalls. We are all flawed. We don’t see eye to eye. As one of my favorites would say, we are all assholes to each other and ourselves. The solid truth is that I care way too much. I am way to loyal. And for these traits, I expect far more out of society and it’s individuals than I should, though I will not sacrifice my standards.

It’s been a rocky road (which, by the way, was my favorite ice cream as a kid), but I know some of the best people on this Earth because I didn’t settle for anything less than love and care.

My mom was always horrible at hiding things. She couldn’t hide from me that we were poor, though she rarely tried. She referred to food stamps often and we lived in a trailer park. She told us right off the bat we were getting toys for tots stuff for Christmas one year. There was a little interests sheet she had to fill out so they could try to match us with toys that would hopefully fit our desires. Present wise, it was bad. They gave us dollar store dolls with hair that came out too easily and plastic that dented at the slightest touch. They were impossible to fix - like an off-brand bottled of water. It wasn’t that toys were cheap that made it bad, it was that we didn’t play with dolls. I was probably eleven or twelve and my sister was in high school and it just wasn’t us. We don’t have pictures of that Christmas, probably because we couldn’t afford the film.

On years she saved and bought presents, I always knew where she hid those, too. At first it was in the cabinets, above the washer and drier, shoved behind towels and double or triple wrapped in Kmart bags. After she realized that spot was useless, she hid them in the nook in her closet that expanded past the boundaries of the sliding doors. Then it was the shed dad built us that was kept locked for the mass amount of tools she housed there. There was a spare, though, and I knew right where it was. Finally she moved them to the toolbox in the bed of her little Mazda pick-up, the white paint chipped and rusted. She had the only key and while we both knew they were there, we also knew there was no getting in there.

What she tried to hide most and what I believe I always hid my knowledge of, was how lonely she was. I’m a nostalgic sort. I would go through the whole house and dust and touch and inspect. The empty Huckleberry Cream Soda bottles and the ankh mom had molded from clay. The bamboo goblets and the 3D puzzle statue of King Tut. Mom’s jewelry box. Her drawers full of notebooks with lyrics and poems I thought she had written. Instead they were songs she’d heard and lingered on, written word for word and filled hundreds of pages. All of which were yellowed. Dawning from before my birth up to the years I first found them.

She worked a lot. At one point, she was the manager of three separate departments in Kmart: auto, hardware, and toys. I would go in before and after school and help her front board games or Matchbox cars. They laid her off mere months before her ten year anniversary but while she was there, she would come home, kick off her shoes, and sit in her bedroom, leaving my sister and I to occupy ourselves.

She hid her chocolate stash in her dresser drawers - easy. She’d go to work and I’d hang out it her room, watch movies, and chip away at it. I’d stand on her bed and belt out Panic! at the Disco.

I’ve always had a lot of anxiety. When I was younger, I dealt with some anxiety induced insomnia. I would lay wide away in my bed and any noise was a sign of an intruder. That creak in the linoleum was not the cat, it was the systematic murder of my mother and my sister. If I were to step outside of my bedroom, I would find them both in their rooms, dead. Blood everywhere. I would wait for an hour after the last violent noise,walk silently to my door and open it slowly, looking for signs of the massacre I’d imagined, then walk down the hall to my mom’s room and open her cracked door even more slowly.

There she’d be, fast asleep in her ragged red flannel in the fetal position, the blankets disheveled. And every time I knew, there would be no sleep for me if I didn’t sleep there. So I’d crawl in. Sometimes, she would turn over and wrap her arms around me and sometimes she would tell me to go back to my room, though I don’t know that I ever actually did.

Later, after I told her why I came to her room, she said I should have told her. She would’ve done something. There was nothing she could have done, though, beyond letting me sleep there. Letting me make sure she was safe.

I was able to predict her mood by the songs we listened to on the way to town every morning. If it was Alanis, she was angry - ramped up and ready to take on the bullshit that is misogyny. If it was Train, she was hopeful and happy, or at least content. Matchbox Twenty was for when she was unloved and unwanted.

She was never either of those things, but being loved and wanted by your daughter is never quite the same.

When Jess and I grew tall, my small mother took to calling us her Amazon Women. Her protectors. Her girls. It was around the time she actually started to shrink in size and I started countering her arguments with “I can lift you."

Physically, I could. Emotionally, I’d like to think the same. The time has come and gone where I was the same age as she when she had her first daughter. I imagine myself in her position: living with an alcoholic husband and a small child and I don’t know how she did it. She was so strong.

I’ve always been better than her at hiding. The anxiety. The depression. The crushes. The outings into the desert. Bike rides into town. My sister’s secrets. And my own.

It was my last semester at University of Idaho that I realized hiding was the reason I didn’t feel connected to anyone. The reason I’d stop letting myself feel anything. I was too afraid they wouldn’t want me for whoever I was - I honestly didn’t know, anymore, who I was.

I think we shared a journey. I did mine without a husband and two crazy kids, but in the end, we both lost a lot to get back to who we are and what we truly want. It’s taken a lot for us to let ourselves have it.

It’s been years since it was just Mom and I against the world and, thankfully, she’s not lonely anymore. She finally found someone who doesn’t make her write Nicselfkleback songs in 49 cent spirals. And she replaced me with a cat that she spoils (Mom, Miss Kitten is fat, admit it to yourself). I miss her every single day, but just as I told her when I was little and showed the first signs of awful math skills: I love her. Ten to a thousand. And no manner of miles or mountains or live in boyfriends or fat cats she clearly loves more than me is going to change that.

Although this meta-photo of her might…

Christmas means a hell of a lot to me. Our photo albums contain, mainly, play-by-plays of at least three of them - taken before my sister and I decided we were no longer comfortable with the camera on Christmas morning. The pictures are out of a time were my anxiety, while existent, was not nearly as prominent as it is now. Panic attacks manifested only once every two to three months, though back then I didn’t know that was what they were.

Those pictures contained everyone I loved most. They were before my dad would lose my trust and my heart. Before my sister stopped relating to my mom. Before I accepted what I already knew to be the truth about Santa. Before my cracked family finally shattered and slid across hardwood floors in all different directions.

Mom and I held it together for one year after my sister left. I put up the tree as soon as I could and, as per our unspoken rule, it was kept lit every moment of the season. Christmas Day, mom and I sat alone in the living room opening the few gifts that had been sprinkled in the cavity underneath the tree.

The truth is, when you get older, the holidays are not the same. You don’t always make it home and, and if you have a mom like mine, there won’t be decorations in the house if you’re not coming. A few years ago, my extended family had a dirty habit of forgetting to invite me until two days before. Now that my dad isn’t in jail, they he won’t let them forget, but that’s a whole different box of awkward.

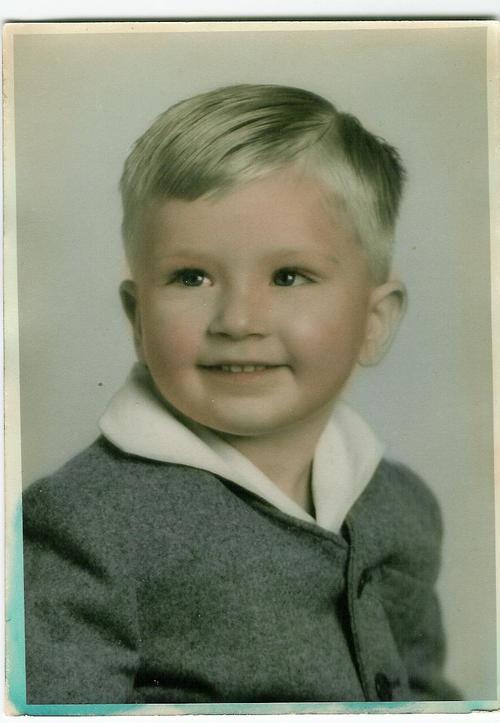

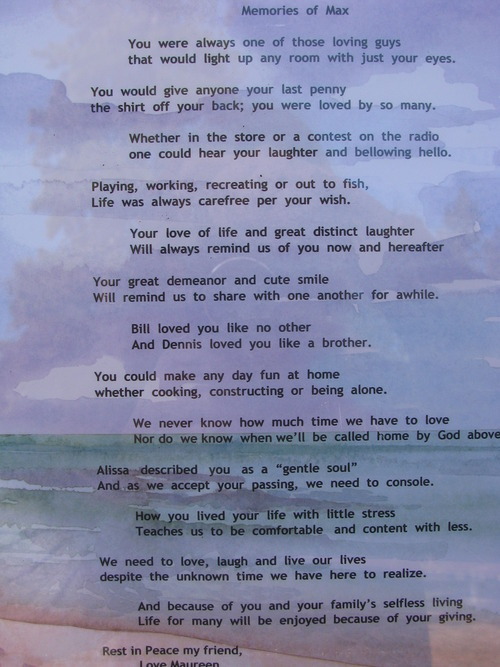

My favorite older Christmas I ever had was at my Uncle Max’s house. He was this pot bellied man, either reaching for the peak or at the top of the hill already - I never really confirmed age with him. He had a little guest cabin of sorts on his parent’s property and he invited everyone over for a little get together. Instead of giving traditional gifts, he gave scratchers - a cheap, but exciting alternative.

When Mom, Apa, and I got there, we were late, as per usual. Apa, my step-father, Phillip, was in late stages of Avascular Necrosis even then. I’ll explain more about that later, but basically parts of the bone in his hips had the texture of the inside of a malt ball that had gotten a little wet.

I left them in the car to make the rounds and assure everyone that Apa was there, he just needed a minute.

Uncle Max found me and asked if I’d picked a gift yet. He directed me to the window sill where there were still five tickets left and told me to pick whichever one felt lucky.

I meditated on it for a moment and picked a green one. He handed me a quarter and said “That’s yours. Now go for it."

He disappeared down the staircase and outside to the fire. My cousin Glenn sat on the couch behind me on his phone as I scratched, not knowing the rules for the ticket entirely.

$3

$10,000

$20

One by one I scratched.

$10,000

$3,000

$1

On second thought, I should have grabbed the Bingo one. I liked the Bingo one.

$30

$2

$10,000

"Oh my god.”

“What?"

I had forgotten Glenn was there.

"Oh my god.”

“What??”

“I don’t know the rules.”

“Sadie, what?”

“I think I won ten thousand dollars.”

“Come here.”

I turned from the sill and went to the couch. He grabbed the ticket from my hands and studied the game board very carefully for a few minutes.

“Holy shit."

"Did I win?”

“I think you did.” He said, “I get half for helping.”

“No, Glenn, that’s paying for my college.”

I’m not even kidding. These words came out of my mouth. Repeatedly. “I’m going to college!”

Nerd.

Also, ten thousand dollars for college? I was incredibly naive at sixteen.

I grabbed the ticket from his hands and ran downstairs to the fire screaming “I’m going to college!"

Max grabbed me by the hand and took the ticket from me. "No. No way.”

“Yes!"

"I bought this. This is mine.”

I snatched it back. “It was a gift, bitch. Where’s Phil?”

“Still in the truck.” I hear from the other side of the fire.

I have to explain to you here that with anxiety and depression factored into my life, I consider this the single most happy moment of my life. Who wouldn’t? Money was a fraction of the factor it had been only moments before. I have always been poor. I don’t think for more than a blink of an eye my mom ever made ten grand a year and she was the manager of three separate departments at Kmart for a good couple of years.

This was a concentration of a full year’s salary at my mom’s peak year. This moment was the stress release of the century.

“Mom!” I yelled, running to the truck. “Phillip?!"

I reached the passenger door on the Chevy and yanked it open.

"What’s up, kid?” Apa asked.

I didn’t even breath. “I won ten grand! I’m going to college!”

My mom: “What?”

Max: *singing*

Phillip: “Let me see.”

I handed him the small rectangle of paper and he studied the game. He flipped the card and read carefully for a moment before pausing.

“You didn’t win, kid.”

Max: *singing* “I got a golden ticket! I got a golden ticket!

"What do you mean I didn’t win?”

“Read the back.”

He hands me the ticket as Max starts to walk over from the fire.

Winning tickets of 10,000 or more must submit claim form by mail. Claim forms supplied by Santa Clause. All winning tickets must be validated by the Tooth Fairy and conform to her game rules. Winning prizes may NOT be claimed anywhere, so forget about it! All winners are losers and must have an excellent sense of humor.

You would have thought my heart would have been absolutely crushed, what with Max shouting “I’m going to college!” and laughing himself to the ground.

No. “I hate you.” I said, laughing myself. “I hate you so much."

He never apologized, he had no need, but he did give me a big hug goodbye that night.

I spent weeks searching for something to get him back with. That search ended with an aneurysm. Did you think this would end happily?

He walked around the bay for a full day with a runny nose and a headache. He didn’t tell anyone. He didn’t complain. Good natured to the end.

My last Christmas with Max is still regarded as one of my favorite Christmases. It held all of the disillusionment of adulthood without any of the anxiety or disappointment.

We still miss you, Max. Merry Christmas.

I owe you something not sad. Look at those nerds.

My Grandpa Gary is a rebel, that’s what he says. He is loud and crass; he will say exactly what he thinks at any given moment, without hesitation. If you ask him something, he answers honestly with no thought of subtlety or fear of consequence.

Oddly enough, the rebel I know is part of one of the most reserved families I have ever seen. While he was off doing whatever was considered inappropriate to them in the early sixties, his mother, Katie; step-father; and brother probably continued to eat breakfast and dinner at their proper place settings, they may have prayed, and they certainly didn’t speak about what Grandpa Gary might be up to. Somehow, I can’t imagine them really communicating much; least of all when it came to Grandpa’s biological father, Herman, and why he, apparently, didn’t exist anymore.

It never occurred to me that some rogue part of my parentage had seemingly disappeared into the great vat of rice that is the world’s population. I didn’t realize that the great-grandfather I had always known was only a that by of marriage. No one ever spoke about it. I suppose I did wonder how Grandpa Gary could fit into their family portrait. Between his quick lips and his avid nature to roam, there was a distinct contrast. His home was any city, town, or campground; a truck and trailer, and the open road. He had three companions. Two dogs: one large, shaggy and black named Bear, the other a protective part wolf named Shoshona. The last was a short, thin woman with dark hair and an amazing knack for entertaining his grandchildren with “This piggy went to the market…” - well, it entertained me. They only made an appearance in our lives every once in a while, but to see them was the most amazing treat. I don’t remember a time before this group, so if Grandpa Gary had ever been clean cut and unspoken, I have trouble picturing it.

As I got older I started to see the differences between my Grandpa and his family. Around the same time, my mom became very interested in our ancestry. Being more exposed to Gary than to his family had fostered in my mom and me, a proclivity toward curiosity and the idea that something might be a secret made it more important to uncover. With unrivaled tenacity, she found Grandpa’s real father, Herman Moon, in Texas but she found him too late.

Grandpa Gary’s mother, Katie, would not talk about Herman, not in detail, and she was the only one we knew with any knowledge of him. Why Herman left and why he never came back, why he never called or wrote, why he never cared was lost. Any questions would be brushed off and deeper inquiries were met with rigid silence.

Years later, Mom got in touch with a woman named Dorothy. Dorothy was Herman’s niece from a second marriage and Dorothy knew a lot. A lot by our standards, anyway, and she had no problem talking.

I’ve always heard that cliché phrase about a woman scorned and thought it trite and silly. I’d never seen a woman in such a rage she would thoroughly ruin the offenders life in some form or another. I couldn’t quite capture the image in my head of Katie having a wrath, let alone executing it. Yet, when Grandpa Gary was around two years old, Katie was admitted into a hospital where she stayed for treatment of what is assumed to have been a venereal disease. I’ll never know for sure, but the belief is that Herman had been having an affair. When Katie was released she took Grandpa and went to her parents’ without Herman. She didn’t go back.

They divorced and Herman moved to San Francisco. He married a woman named Mildred but he never forgot his son. Katie had never told us that Herman had decided to try for custody or visitation of Grandpa Gary. When he and Mildred showed up at her house they were greeted with shotgun and told not to come back. They went home to California, but Herman didn’t give up. He handed a lawyer five thousand dollars and asked him to help. Nothing ever happened and Dorothy never heard him speak about the lawyer again. We’d never heard of the lawyer at all.

Herman never stopped talking about his son, though. Dorothy said he kept a picture he’d had taken of Grandpa in focal points of his house without fail. He was so proud of whatever his son could have been; it probably never really mattered to him what, exactly, it was.

This is the part of the story where I imagine Herman’s side of the family. I can picture his sisters so clearly, standing in their kitchens, talking to Herman over the phone. I picture them asking after a particularly awkward silence “So, have you heard from Katie? Anything about Gary Lee?” And when I think of his response I think of a silent head shake and a very clipped “No.” That is the end of the conversation, in my head. They say quick goodbyes and hang up. Then maybe Herman spends a drawn out moment looking at that picture of his son, frozen in his mind at two years old.

Herman and Mildred divorced, but they stayed in touch and Dorothy remained a big part of his life. He worked in finishing carpentry in Hollywood. He married a third and final time. He must have messed around on this woman as well, because when she left, she took everything.

Dorothy found him his own place where he lived until he died, with Grandpa’s picture in the forefront. As his days dwindled, he began to ask her if she’d found or heard anything about Gary Lee. Only a few months after Herman died, mom found him, or rather his obituary, online. When she did, she cried. She had just missed him.

When I got home the day she spoke to Dorothy, Mom was restless. She didn’t look me in the eye, and I could see a million images passing behind her own. After she rambled off the entire story, she exhaled any confidence she may have had and told me she had no idea how she was going to tell Grandpa Gary. She had no idea how she was going to let him know after all those years of stolid silence, how loved he was. How wanted.

When Mom did talk to Grandpa, all she could do was give him Dorothy’s phone number and tell him to call. Dorothy sent him the watch that Herman had been wearing when he’d died and a few of the pictures that she had.

Neither of these things can rewrite time. Herman would never know his rebel son who roamed around the country, the granddaughter that tracked him down, or the great-granddaughter that is writing about him now. My Grandpa Gary will never know his father, only that the man had never stopped looking for him, never stopped wanting him. Only that, if he had been able too, Herman would have been and done anything for Gary. My mom will never know her grandfather, she’ll only ever have photos to pour over and memorize and second hand stories to think about before she falls asleep. I will never sit next to him, close my eyes, and listen to the tone and pacing of his voice as he talks about the people he’s known and the places he’s been. Now it isn’t the whys that we will never know, it is the hundreds of stories lost between us all. The stories, I think, we would have gladly shared, good or bad.

Grandma Katie passed in 2009, taking her justification with her, locked tight away. I can’t say if she ever knew that we’d found Herman and what was left of his family. I can’t say that she knew he’d died. More than anything, I can’t say she ever forgave him or if her scorn went away. I’ll never understand why an affair may have caused her to separate her son from his father. Perhaps there was more to it that we’ll never know.

Katie was a private woman who held her head high and stuck to her decisions like she’d made them with crazy glue. The last time I saw her, she was in a nursing home in Tennessee. She had been injured getting out of bed and as a result, hadn’t walked in weeks. But on that day, as we were leaving the home, we watched as she scurried down the hall with her walker and yelled at the physical therapist to hurry up.

I don’t remember her as the woman who kept her son from his father or who kept her tongue like using it would create a crack in the Earth that the sky would crumble into. I remember her as the woman who did what she thought was right to protect herself and her son, though I find myself wishing she hadn’t have been so stubborn about Herman. Whether he was a great or terrible, sometimes it’s better to cope with disappointment instead of uncertainty. Sometimes, some decisions are not yours alone. Sometimes they have the ability to vastly alter someone else’s world. But when you’re caught up in the moment, sometimes you just have to decide to speak or remain silent. The art in it is to know when you might have decided incorrectly and when to concede.